One person in every hundred has schizophrenia, and 85% of cases occur in families with a known history of the disease. But despite being so common, the causes of condition remain shrouded in mystery. Now scientists have found a new way to gain a fresh insight into the disease - by propagating patient's own nerve cells in a culture dish.

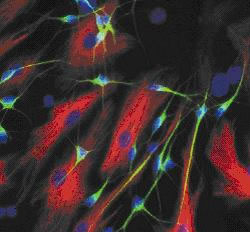

Writing in Nature, Salk Institute scientist Fred Gage and his colleagues explain how they took skin cells from four schizophrenia sufferers and then, using a genetic technique, reprogrammed these skin cells to become stem cells, which they were then able to turn into brain cells that could be cultured and studied. Compared with control neurones produced using the same technique but starting with skin cells from non-schizophrenics, the nerve cells produced from the patients showed reduced connectivity - in other words made fewer chemical connections called synapses - with other nerve cells and they also put out fewer nerve branches.

Writing in Nature, Salk Institute scientist Fred Gage and his colleagues explain how they took skin cells from four schizophrenia sufferers and then, using a genetic technique, reprogrammed these skin cells to become stem cells, which they were then able to turn into brain cells that could be cultured and studied. Compared with control neurones produced using the same technique but starting with skin cells from non-schizophrenics, the nerve cells produced from the patients showed reduced connectivity - in other words made fewer chemical connections called synapses - with other nerve cells and they also put out fewer nerve branches.

The researchers also exposed the cells to a number of antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia; one, called loxapine, reversed some of the observed connectivity deficits. But even more powerfully, the team were also able to compare how the gene activity profiles of the schizophrenic neurones differed from that seen in the healthy nerve cells, identifying in the process 596 genes that were being expressed differently in the two cell types. One quarter of these have previously been tied to the condition, but the others represent new avenues that could be followed, including from a therapeutic perspective. Indeed, exposing the cells to the antipsychotic drugs produced significant changes in the activities of a large number of genes.

According to Kristen Brennand, the lead author on the paper, "These drugs are doing a lot more than we thought they were doing. But now, for the very first time, we have a model system that allows us to study how antipsychotic drugs work in live, genetically identical neurones from patients with known clinical outcomes, and we can start correlating pharmacological effects with symptoms."

- Previous Mankind talked his way out of Africa

- Next Self-righting bicycle

Comments

Add a comment