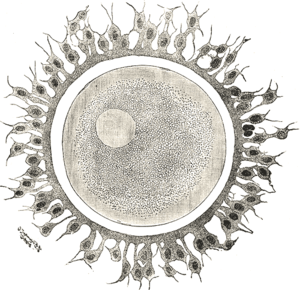

Unlike men, who are constantly producing new sperm cells, women have to work with a fixed number of egg cells from birth. Us girls are born with around 800,000 immature, dormant egg cells, known as follicles, and a couple of thousand of these are activated by hormones during each menstrual cycle, counting down our biological clock until the menopause. So there's a certain amount of time pressure on becoming a mum - at least in the biological sense. But now an international team of scientists, writing in the journal PNAS this week, have found a way to reactivate these dormant egg cells. And it could have big benefits for infertile women, or those who have had their ovary tissue frozen before treatment for diseases such as cancer.

This is work from Jing Li at Stanford University in the US, and researchers in China, Japan and America, and it all hinges on a gene called PTEN. Using mice, Li and her team found that shutting off PTEN using a special chemical could activate the dormant egg follicles in the ovaries of newborn mice - and when they transplanted these follicles into adult female mice whose ovaries had been removed, they could produce mature eggs and even baby mice.

This is work from Jing Li at Stanford University in the US, and researchers in China, Japan and America, and it all hinges on a gene called PTEN. Using mice, Li and her team found that shutting off PTEN using a special chemical could activate the dormant egg follicles in the ovaries of newborn mice - and when they transplanted these follicles into adult female mice whose ovaries had been removed, they could produce mature eggs and even baby mice.

It turns out that PTEN helps to switch off another gene called PI3K - this is makes a molecule that sends signals inside cells. Normally, PI3K works on a protein called Foxo3, changing its location inside follicle cells and triggering the follicle to mature. So blocking PTEN with the chemical means that it can't switch off PI3K, so PI3K can act on Foxo3, triggering the egg maturation process.

As PTEN is also involved in protecting our cells from cancer, there is a concern that blocking it might cause cells in the follices to develop into tumours, but luckily the researchers didn't find any tumours developing. Instead, the activated follicles developed into mature eggs, which could produce healthy baby mouse pups. And these pups grew into adults and had healthy babies of their own, suggesting there aren't any fundamental inherited problems with the cells or the DNA within them.

Obviously, it's more challenging to do these experiments in humans, but the researchers managed to do some tests on ovary tissue that had been taken from women having operations for ovarian cancer. Treating them with the PTEN-blocking chemical caused follicles to mature and produce egg cells, but unfortunately it seems that there might be some problems with them. So it's not certain that it will work in women, and a lot more research will need to be done before we know if we can use the technique to treat infertility.

- Previous Battle of the Bugs

- Next Burning bush brings biofuel hope

Comments

Add a comment