Why are measles cases surging?

In this edition of The Naked Scientists, what’s behind a sharp rise in measles cases? We explore the origins of measles virus 2000 years ago, why the agent is regarded as the world's most infectious virus, how the agent causes disease, how measles vaccines work, and why cases are back on the rise...

In this episode

Where does measles come from?

Paul Duprex, University of Pittsburgh

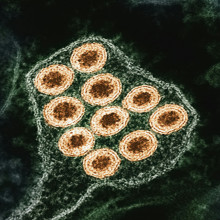

Measles should really, by now, have been consigned to history. Exclusively an infection of humans, and with lifelong protection conferred by a vaccine, it’s potentially eradicable. We did it with smallpox; we’re close to the same with polio, and we thought we were getting there with measles, with cases down over 90% compared with the early 1960s. But now measles infections in many countries are surging again, and this week we’re going to find out why this is happening, what the unabated infection does to a person, and what we can do to curb the growing global outbreak. But first, where did measles come from in the first place? The smoking gun seems to point directly at a now-defunct disease in cattle called “rinderpest”. And we think that, as human populations grew, and animal husbandry took off, bringing large numbers of us into close contact with each other and with animals like cattle, we opened the door to the disease jumping the species barrier and becoming a new human infection, probably about 2000 years ago. The disease presents with a fever, cough, and a runny nose. Soon, the telltale rash appears, followed by potential complications: pneumonia, encephalitis, and even death. In fact, over 100,000 people still lose their lives to measles each year. And because measles can also erase immune memory, it leaves us vulnerable to other deadly infections in the aftermath. Paul Duprex , is the director of the Center for Vaccine Research and a professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at the University of Pittsburgh…

Paul - Measles is a virus which uniquely infects people, but we know that human viruses come from animal sources. And the best idea, looking at generic data, says that measles came most likely from cattle. And that's not in the last 100 years, but in the last couple of thousand years, we would imagine that there was an ancestral virus which infected cattle. And whenever people came in close contact with those cattle, the virus jumped from one species to the next and began to explore new hosts.

Chris - Did it behave like measles in the cattle, or was it a completely different manifestation, this Rinderpest ancestor of measles, if I can put it like that?

Paul - Well, that's a really good question and actually a very hard question to answer, because of course we don't have photographic evidence, we don't have very much written evidence. So what you have whenever you have a cross-species jump, whenever viruses jump from one species to the next, it's not really good if you're a virus to kill every single one of the species that you infect. If you need to survive as a virus, you need to have a host to infect. So killing all the hosts isn't a good thing, and typically what happens after those first jumps is you get a lot of disease at the beginning. And then as decades, centuries, millennia progress, the disease becomes less virulent, less likely to cause significant problems for the host.

Chris - Presumably, given that measles is ridiculously infectious, it causes acute disease. A person has it, they're very soon infectious, and then they're very soon either immune for life, or let's face it, in some people's unfortunate cases they're dead. In those cases, it means it's got to be jumping from one person to the next very, very rapidly, hasn't it? So there must therefore be, back in history, a threshold effect, when there must have been enough people around to get it to sustain. So it could keep on infecting people in that way, because if there weren't enough people, it wouldn't have been able to maintain a chain of transmission like that.

Paul - That's right. As people moved from nomadic lifestyles into cities, the population sizes became bigger and bigger, and eventually they were large enough. You need about 250,000 to 400,000 people to sustain measles in that population. You might ask, why would that be? Well, the really interesting thing about measles is, once you've had it once, you will not get that disease again. So that virus causes something that we call lifelong immunity. So if you're a virus which can only infect once, you need lots of new babies being born year on year for enough susceptibles to be brought in, so that you can keep maintaining your transmission.

Chris - And that presumably is also why measles is so infectious, because it's got one chance to make that infection, so it makes sure it doesn't miss.

Paul - Measles is the most infectious human virus on earth. It can hang around in the air for a couple of hours after someone sneezes, but it also has the ability to transmit before you know that you are infected. So for example, we think of measles and we know that measles causes a rash, but four days before you see that rash, you're able to transmit measles. You don't really feel too bad. So the virus is an absolute master of infection. It's super, super infectious. It hangs around in the air and it can transmit from a person who doesn't even know that they have the disease.

Chris - How did people react to it then? Back in history, what sort of impact was measles making and what was the human response?

Paul - Well, measles was really seen as just a normal thing that happened whenever kids grew up. So you were born, you were a toddler and then you got this red rash and people just literally thought that this was part of growing up. They didn't know about viruses. They didn't know about infectivity in those days. As time progressed, of course, people realised that some of those people who got that red rash were really very sick indeed. Remember, there was no way to protect people. You really just treated the symptoms. You couldn't protect people against the disease. Rather, we had to develop as a community vaccines and vaccines really changed the landscape for measles in the most incredible way.

Chris - That was starting in the 60s, wasn't it? We had our first measles jabs.

Paul - That's right. In 1963, in the United States, a number of individuals were able to generate a weakened form of measles. So what they did is grew it in cells which were not from humans and they were able to make that virus less virulent, less likely to cause disease, but it still infected the person who was vaccinated with it. And what was really wonderful about the measles vaccine is with two doses gives us lifelong immunity from that disease. So that was the total game changer in the 1960s.

Chris - And because this is exclusively now an infection of humans, does that mean then this is potentially an eradicable disease like smallpox has been eradicated? Different virus, but possibly the same strategy. We vaccinate enough people and we can get rid of it completely.

Paul - Yeah, that's absolutely possible with measles. Remember, we talked a little bit about where measles came from, this cattle virus, and it has been possible by the use of a really efficacious vaccine to eradicate the cattle cousin of measles, Rinderpest virus. So we too should be able to eradicate measles just like Rinderpest from the world.

How does measles make us sick?

Melanie Ott, Gladstone Institute of Virology

What does measles do to a susceptible person, and how? It spreads via the respiratory route. From up to 4 days before they know they’re unwell, an infected individual is breathing out virus particles, which linger in the air for hours before someone else breathes them in. If that person isn’t immune, they settle in the respiratory tract and spawn a fresh infection, which spreads into immune cells that ultimately transmit the virus throughout the body’s tissues, which is why no organ is off-limits. It can affect the eyes, brain, lungs and even the intestines. It also wipes out immune memories of past infections, meaning we end up catching things we had already learned to fight off, all over again. For some, the infection and the complications are so severe, it can kill them. Taking us on a tour of how measles works and the way it breaks in, here’s the Gladstone Institute of Virology’s Melanie Ott…

Melanie - You can imagine it like a little particle that is endowed with a lot of glycoproteins and other molecules that make it latch onto cells and invade them perfectly. And so the virus is very good in getting into our airway lining and there it's not very discreet. It actually pokes holes into neighboring cells and the cells where it is infecting. And not only exchanges viruses, it exchanges whole parts of the infected cell. So it can basically spread like a wildfire until it reaches the immune cells that are in our airway lining. And from there, it takes it into the lymph nodes, into the whole body, and especially can also take it into the brain.

Chris - So the first exposure to measles, we effectively get a lung infection, which then hitches a ride on the immune system to the lymph glands, and then the whole body is your oyster. It can go anywhere.

Melanie - Pretty much. And because the virus is really very good in activating our immune cells so that it can spread without much opposition, it can go into many different tissues and can do harm. One in five people end up in the hospital and they often end up in the hospital because of pneumonia. So problems with breathing. But the other thing that we are very much worried about is encephalitis or the infection of the brain is really one of the things to avoid in measles infection and to watch out because that is something that can be fatal at the end. It also has a nasty habit, the virus, to actually become latent in the brain. And then you think you have dealt with the measles very successfully and all in a sudden it reappears, not in the form of the little red dots and the other infections, but it is a progressive encephalitis that is almost 100% fatal.

Chris - And how does the body respond to all this? How does it try and fight off the virus?

Melanie - If we have not had any contact with measles before, the virus is quite well equipped to overwhelm the immune system very fast. It has certain proteins that inactivate our sensors and our cells that would otherwise alarm and say, well, there's the virus coming in. But viruses in general and measles specifically have evolved some very effective mechanisms to inactivate this. And then it gets also into the immune cells that are patrolling our bodies and it can do very characteristic harm to them. And one of them is to wipe out our immune memory so that we are not only having a problem dealing with our current measles infection, but we also have a problem in the future to deal with other infections.

Chris - They dub that immune amnesia, don't they? So does that mean then that if you catch measles, it basically wipes out your immune memory so that you become susceptible to all the things you've spent the previous however long you've been alive for learning to fight off? You're back to square one.

Melanie - Yeah, pretty much. I compare it to a virus in our computer who can wipe our hard drive or rewire that it doesn't function anymore. And it's really exactly the same principle. So what happens is that the virus, by being able to infect our immune cells, can specifically infect and destroy these memory cells that we have. Now, if we eliminate these memory cells, we basically eliminate our previous history of infections and vaccinations. And that leaves us vulnerable to totally different infections in the future. And we might even have to go back and do our vaccinations again.

Chris - And if someone isn't so lucky as to just get away with losing their immune memory, why does measles claim some people's lives? What happens to them? And what sorts of numbers of people succumb to measles around the world every year?

Melanie - So we have one in five who go into a hospital which is quite high. One in 20 who are developing a lung infection. One in a thousand who are developing a brain infection. And then we also have the same number, one in a thousand, that actually die. And so often the brain infection is limiting, but also a lung infection can become limiting if you're not in the hospital and can't get help.

Chris - So if you've got those sorts of frequencies, the numbers around the world then, given how common measles is, the numbers of mortalities must be quite high.

Melanie - Yes. And that's why I think public health officials were so keen on from the beginning to somehow get rid of this virus because it is a dangerous virus.

16:07 - The MMR vaccine and vaccine hesitancy

The MMR vaccine and vaccine hesitancy

Andy Pollard, University of Oxford

The tables were turned very much against measles in the 1960s when the first mainstream vaccine was developed. It was later rolled into a triple jab called MMR - which has been a cornerstone of public health, protecting us from measles, mumps, and rubella. Its effectiveness hinges on very high levels of population uptake - in the region of 95% - which are needed to counter the exceptionally high infectivity of measles. And, unfortunately, for various reasons, in recent years, uptake has slipped below this essential “herd immunity” threshold, which is why the disease is making a comeback. Andy Pollard is an expert in pediatric infection and immunity from the University of Oxford…

Andy - Well, we've been using vaccines to defend ourselves against measles since 1963, but really with very high coverage. We didn't really get to there until the early 1990s here in the UK, and we give the vaccine to children starting at a year of age with a second dose that currently is given just before children go to school. But actually at the end of this year we're going to change the timing so the two doses will both be given in the second year of life, one at about a year of age and the other at about 18 months of age.

Chris - Does that not create a sort of window of opportunity for measles in very young kids who could get it before they get vaccinated? And if so, why have we got that particular age selection for this vaccine?

Andy - Well, if we didn't have very high coverage and measles was circulating, it is absolutely true those under a year of age would be extremely vulnerable, and in fact that's where many of the deaths occur in countries where there's a lot of circulation of measles. The problem with the vaccine is if we go too early, then the vaccine doesn't work as well because the babies under a year of age still have some of their mother's antibodies in their blood, and that stops the vaccine from working so well. It inhibits the type of vaccine we use, so we have to wait until around a year of age for the first dose.

Chris - We're relying then on what's widely dubbed herd immunity. When you say high vaccine coverage, that's what you're getting at, isn't it? Getting to lots of people in the population so that the number of people who are vulnerable are so sparsely distributed that the chances of someone who can get it bumping into someone who has got it are very remote.

Andy - Absolutely, and of course that's different for different infections. So for measles, you need really high coverage, over 95%.

Chris - And presumably the fact that we are now seeing outbreaks in many countries, including those that have enjoyed measles elimination status, no circulating cases for decades, that is a reflection on a lower level of uptake. We're now under that magic threshold for herd immunity then.

Andy - Yes, and if you were below 95% for one year, you might get away with it, but if you're below 95% year on year, then the number of people in the population who are susceptible builds up and it builds up until you reach a point where there's so many people that the virus arrives and it just transmits like wildfire. And then anyone unvaccinated becomes at risk of severe disease and death or brain damage as a result or severe pneumonia. But there's a particular group of individuals who can never be vaccinated who are always vulnerable if the virus arrives and starts transmitting, like those who have a problem with their immune system, either because they've inherited it or because they've developed cancer and they're on treatment or some other conditions where we use immunosuppressive drugs to treat inflammation.

Chris - What are your thoughts then on what is happening in Texas? We've seen a big outbreak there. We've also had the European Union saying they're very, very worried about the big uptick in cases. They're talking about thousands of cases across Europe. And home here in the UK, we've also had many, many cases more than we would expect normally.

Andy - The reason for all of those outbreaks is because coverage of vaccine has dropped below 95%. And in some parts of this country, in the UK, vaccine coverage is well under 70% and has been over a number of years. Fortunately, that's in pockets. So it's not the whole country has low coverage. But as soon as you have a pocket where that's low in that region, you're going to have high transmission. The worst areas affected have been in London, parts of the West Midlands over the course of the last couple of years. In the US, it's a similar picture. We've had a lot of anti-vaccine sentiment, particularly in the southern states such as Texas. And there are some communities, religious communities, who don't believe in vaccination. And the outbreak in Texas in the last few months really seems to have been initiated in the Mennonite community who don't vaccinate their children. So once the virus was introduced there, it spread. And of course, it's then spread across the whole population because they've had low coverage across all Christian denominations, as well as in the Mennonite community itself.

Chris - So if you're talking to a parent who says they're uncertain or they're concerned, what do you say to reassure them?

Andy - If I'm talking to a parent, which I very frequently do, about measles vaccination, I always talk about the disease, the risks of the disease itself. Because I think that's a really important context to put this in. Now, when I started in paediatrics more than 30 years ago, around a million children a year in the world died of measles. And just before the pandemic, we'd got that number globally to less than 100,000. So a 90% reduction in deaths. So this is one of the most important viruses to prevent because it's so good at finding children who are vulnerable and causing severe disease and death. And the vaccine itself is one which is extremely safe. It's been tested in great detail because there had been concerns in the past raised about safety, which turned out to be incorrect. And so we talk about those studies and the concerns, which often parents have particularly a suggestion that came up at the end of the 90s, that there might be link between the vaccine and autism, which has been completely discredited with very good scientific studies to show that that is not the case. And when parents hear the evidence, and they're reassured by that, those hesitant parents will go ahead and protect their child, because this is really a matter of life and death.

How to counter measles misinformation

Sander van der Linden, University of Cambridge

Anti-vaccination sentiment and misinformation are the leading reasons why vaccine uptake rates have declined and left us exposed to measles epidemics again. Much of this stems from a now-discredited study published in The Lancet in 1998, which falsely linked the vaccine to autism. Andrew Wakefield’s paper was fully retracted and he lost his medical licence to practise. But the damage was done, and it’s fuelled a wave of vaccine hesitancy that persists to this day. So, what to do? Sander van der Linden at the University of Cambridge is the author of Foolproof: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity. His approach centres on the concept of administering “cognitive vaccines” capable of “pre-bunking” misinformation, so audiences are less susceptible to being seduced later by misinformation, which is what he sees as the underlying problem in the modern era…

Sander - Vaccination rates have been dropping over the last few years at the same time where we've seen an infodemic, a rise in unreliable, low quality information that's inundating people. And so this concept of vaccine hesitancy is to some extent due to the rise of misinformation, both online on social media and how people discuss it with friends and family offline. You know, what goes in the vaccine, what the vaccine does to the body, what the incentives of doctors are, the wellness industry, there are lots of things that go into why people are hesitant about the vaccine.

Chris - Do you lay all the blame or nearly all the blame at the feet of social media for this? Or has something else happened to people and their receptivity to this that means this kind of contagion is worse now?

Sander - I think it's worse now. I mean, you do have to contextualise it a little bit. So if you look at imagery from the 1800s, well, of course, Edward Jenner came up with the first cowpox vaccine against smallpox. You already had anti-vaccination activists in the 1800s who drew paintings with cows sprouting out of people's mouths and ears. And the whole idea was that the vaccine was going to change your DNA and you were going to turn into a human cow hybrid. And of course, they used the same tactic with Covid. And so that's been a trope that's been used throughout history, right? The basic idea that the vaccine is going to change your body and that sort of fear mongering. And of course, Wakefield is famous for spreading misinformation about the link between the MMR vaccine and autism. And vaccination rates did drop significantly after the Wakefield paper. And that was before social media. But now we have a massive amplifier, right? And I think part of the way that we interact with technology is that we're exposed to so much more low-quality information from so many more sources. The brain resorts to rules of thumb or heuristics when it's stressed out. Does this resonate with what other people are saying? Do I like this person? Do they sound persuasive? Does it fit with what I want to be true about the world? Does it fit with my pre-existing concerns and fears? We know from our research that Gen Z and digital natives are actually more susceptible to misinformation, and they're exposed to a lot of it. The sort of influencer model now, where instead of health professionals communicating to people, you have people with no expertise or medical degrees telling people that vaccines are loaded with dangerous chemicals and you should be doing natural things instead.

Chris - How do we address this then? What do you think, given what we now see confronting us? We've got multiple continents with big outbreaks now of a disease that we know is eminently preventable but is very dangerous. It does claim lots of lives. It leads to lifelong impacts. What should we do? What's the easiest win? And then what are the longer-term things we need to do?

Sander - Yeah, I think the easiest win, what we should be doing, is to try to immunise people psychologically against disinformation about vaccinations. The idea is that you can actually preemptively vaccinate people by exposing them to the trickery and the manipulation techniques that are used over and over again about vaccinations so that people don't fall for it when it actually comes their way. That would be the full dose in the analogy. So actually, we need public health authorities to do this on a large scale on social media. And over time, one of the things we've learned running these campaigns is that WHO or an official organisation isn't always the best source to diffuse this message. I think increasingly, we also have to rely on the influencer model. I mean, there are doctors who have a public role, who have huge audiences, who are communicating accurate and trustworthy information that could be the vehicle for delivering the pre-bunk or the psychological inoculation. And then in the longer term, I think we need to address some structural issues that we need to build trust with audiences who have lost trust in the mainstream, in official sources. And I think the way to do that is to demonstrate what we call trustworthiness. When you force people with a one-sided message to say you need to get vaccinated, you get often this concept of psychological reactance, which is that people feel their freedom is being restricted and then they're going to do the opposite. And instead, if we tell people, look, here's a vaccination, here are the benefits, here's the side effects, this is your decision, here's why it's important to get vaccinated, to vaccinate your children, people are much more welcoming of that message. They feel less attacked, they feel less pressured, and they're actually more likely to come on board. And also provide structural resources, simple logistical stuff. Some of the best interventions are, do people have access to the vaccine? Are they getting appointment reminders? Are they going to get help to get to their appointment? So just offering lots of opportunities for people to get vaccinated in an easy way, that's going to help uptake as well.

Related Content

- Previous Are seed oils unhealthy?

- Next HALO, Gateway and Vigil

Comments

Add a comment