What can we do about hair loss?

In this edition of The Naked Scientists, we look at the science of hair, why we suffer hair loss, treatments that can slow hair loss, whether wigs are any good, and what happens during a hair transplant?

In this episode

What is hair?

Desmond Tobin, University College Dublin

We rarely stop to think about our hair until it starts to vanish - but it is one of nature’s most versatile fibres. It keeps us warm, helps us sense the world around us, and, for much of human history, it has been a powerful social and cultural symbol. But it’s also fragile, and when its growth cycle falters, the change can be unsettling. We'll find out why we lose our hair - and what we can do about it - a bit later. But first, what exactly is it? Desmond Tobin is a professor of dermatological science at University College Dublin and director of the Charles Institute of Dermatology…

Desmond – Hair is a remarkable structure. It's a protein-rich structure made of keratin, but it is a very, very tough structure and it's produced by a little factory in the skin called the hair follicle. And the hair follicle is an outgrowth or an appendage of the skin. It's unique to mammals and this particular follicle is a very rapidly dividing proliferative engine that can produce hair, say on the scalp of about 0.2 to 0.3 millimetres a day. And that particular follicle remains embedded in the skin. And what you see growing on the surface and above the surface of the skin is dead keratinised fibre of hair.

Chris - Can you just talk us through that? When the hair follicle makes a hair, is that cells that have been fused together, having been stuffed full of that protein you mentioned, keratin, and they wind together to make the hair? Or do they secrete the substance and it then plaits itself together to make hair? How does the hair actually get made?

Desmond - So at the very base of the follicle during its active growth phase, the root of the follicle contains a little clump of cells called keratinocytes that form keratin in cells and another bunch of cells called the dermal papilla, which is a kind of fibroblast structure. And that's like the, you know, grand central station really of the follicle. Without that little kind of button of fibroblast, you won't be able to make hair. And the interaction between these two different cell types, along with, of course, the pigment-forming cell called the melanocyte, that kind of triangulation of activity allows the progeny or daughter keratinocytes to not only be filled with keratin, but also hopefully be picking up some melanin granules or pigment granules as well, so that the outgrowing fibre, which is a filamentous structure, tightly wound proteins that are very, very tough, get pushed out from the follicle from below at a rate of about 0.2-0.3 millimetres a day. But the follicle is largely permanent, while the fibre is constantly growing out until the end of the hair cycle, and then it stops for a short period of time.

Chris - Just to clarify then, so the keratinocytes, they make the keratin, but do they actually die in the process? So you just get loads of keratin in what would have been a cell and that is glued together to make the hair filament, or is it physically cells sticking themselves together to make that filament that's then extruded?

Desmond - It's neither one nor the other. So we have about seven different types of keratinocyte cell in the follicle, in the lower follicle. You have about two or three of those keratinocyte subfamilies that make the fibre. So you have keratinocytes that make a central unit of the fibre called the medulla, keratinocytes that make the bulk of the hair fibre called the cortex, and keratinocytes that make the very outer kind of like shingle-on-the-roof type of layer called the cuticle. You know, the coordination of these three different keratinocytes forms these three different parts of the hair fibre. But even if you were to take a long hair fibre and cut it at a transverse section and look under a microscope, you would see the cells that originated the keratin still there.

Chris - And as you say, sitting next door to those keratinocytes are melanocytes that can almost spray-paint the hair with melanin to give it its colour. How are different colours or hues achieved then?

Desmond - First of all, there's a very powerful geographic ancestry to pigmentation. It was one of the traits of human beings that was under very powerful evolutionary selective pressure. And as a result, you find that brown, black hair and brown, black skin and brown eyes is the preferred combination of pigment for our skin and our eyes and our hair. And that's largely to give the best defence against ultraviolet radiation. And as humans moved out of Africa and then migrated north where there was much less sun, the brake against having any change from that pattern of colour was lifted. And then we start to see the emergence of many other skin, hair and eye colours, particularly as we see in northwest Europe.

Chris - And lastly, I mean, us blokes, as we get older, we all know we get hairier, up our noses and out of our ears. Now, what's that all about? Why on earth does that happen? And is there any way to stop it?

Desmond - So that's a very good question. And it brings in the whole question of hair ageing. Now, we're obsessed with ageing generally. And it's often very difficult to convince somebody that a turbocharged hair follicle that is producing much, much more vigorous hair growth in their 70s than it did in the 30s is an example of an ageing follicle, where you'd expect things to slow down to a shuddering stop almost. So again, they happen in sites where there can be an influence of sex hormones and shifting levels of sex hormones. And we even see it in menopausal women, for example, where after a very significant drop in oestrogen, their underlying androgens then have a more dramatic influence on their hair. And so they may get hair on their chin and moustache, for example, in a way that they didn't when they were younger, when the oestrogen levels were higher and balanced the androgens for those individuals. So much of these changes reflect changes in hormonal levels as we age. There are certain ethnicities or people in certain countries, like in India, for example, who may have more exaggerated ear hair with age. So there will be some geographic ancestry aspects to it, but there will also be an underlying shift of gear in our hormones. And remember, we don't have in male ageing the kind of cliff-edge effect that women have for their oestrogens, in terms of a male testosterone, which only very gradually shifts gear over time.

Why does hair loss happen?

Justine Hextall

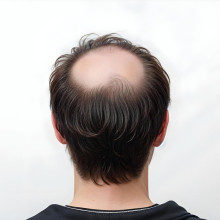

The loss of hair is an extremely prevalent phenomenon. Here in the UK, it's estimated that, by age 50, 85% of men and 40% of women will experience some form of pattern baldness. So what is happening to the hair cycle that Desmond outlined to cause us to lose our hair? I’ve been speaking with consultant dermatologist Justine Hextall.

Justine - If you've lost hair, then that means that something's changing about the hair follicle. Now, it might be, for example, one of the most common causes of hair loss is what we call androgenetic alopecia, or male or female pattern baldness. And what happens is, over time, the hair follicle becomes miniaturised, becomes smaller, so the hair that it produces is no longer this thick, what we call terminal hair, but it's very fine, vellus hair. The follicle eventually becomes dormant, and you get some loss of hair in those areas. And that's what we call male pattern or female pattern baldness. But there can be other causes, you know, of hair loss. So, for example, your body might produce an immune response against the follicle, as in alopecia areata, or you might have inflammation around the follicle, so there might be an inflammatory process, which is effectively destroying the follicle, so you get this scarring alopecia, and this may be caused by infection or inflammation, and that's where the follicle's actually destroyed, and that hair is very hard to get back.

Chris - On the first of those that you just mentioned, androgenetic alopecia, the clue's sort of in the name, isn't it? Androgen, male hormones, because it tends to affect men mostly, but not exclusively, do women get this as well?

Justine - They certainly do, and I think people don't realise that. So, two-thirds of women at the age of 50 will have experienced some hair loss. So, obviously, we see it much more in men, but women will have it, to a lesser extent, maybe less obvious. So, yes, androgenetic alopecia in men, and that's to do with the hair follicles becoming smaller, and that's through a hormone called dihydrotestosterone, and that's an active form of testosterone. Now, we have these androgen receptors in men, specifically, at the front of the scalp, mostly concentrated, and also on the back, on the centre of the crown of the scalp, and that is why we tend to see hair loss in the front of the scalp. So, you start to get this regression of the hair at the front, but also on the crown, because dihydrotestosterone focuses on those androgen receptors, and it causes them to shrink, and they get smaller, and the hair starts to disappear in those areas.

Chris - Do we know why that should happen? Why should a ubiquitous-in-the-body hormone cause a pattern of hair loss like that?

Justine - Heritability is quite high. The genetics in men is probably about 90%, so it depends which genes you've inherited, and it's not about one gene, it's polygenetic. So, there's one important gene called the androgen receptor gene, which we inherit on the X chromosome, so men will get that from their mothers, and because men only have one X chromosome, it's kind of like sitting there, all the cells then will have that gene, and if that's a gene which is going towards hair loss, then it's going to be expressed more in men, for example, than it is in women. But it's not just that X chromosome, there are other inheritances from the father and the mother.

Chris - How does it happen in the women then? Is it that they do get exactly the same mechanism, but because they have less testosterone, it just takes longer?

Justine - Well, the distribution of the androgen receptors in women is more diffuse, it's not in those areas, but there are other hormones in play. So, for example, oestrogen will protect the hair follicles from hair loss, so until someone goes through menopause, there's a protective element. Women are more susceptible to certain environmental factors as well, stress and other hormones, so it's just not so direct, it's more complicated in women.

Chris - Now, you mentioned stress. This is often cited as a cause of either prematurely going grey or premature balding. Is that just someone fantasising, saying, well, I got stressed and they're sort of attaching a significance to a coincidence? Or is there a mechanism behind that as well?

Justine - No, as I said, with epigenetics, certain genes can be switched on through stress, so if you have a genetic propensity towards losing your hair or androgenetic alopecia, say in a man, but you're also in a stressful environment, it can switch those genes on. But also, when we're stressed, and that might be mental stress, you know, with work, or it might be, for example, physical stress, like an operation or certain medications, they can create something called telogen effluvium. So our hair has a growth cycle, anagen, and then it has a catagen cycle, and then what we call telogen, where it starts to rest and then drop. And what happens with telogen effluvium, which can be switched on by stress, is the hair cycle gets pushed towards telogen, where there's increased drop. But because there's a gap of about three months from that being switched on to noticing the hair loss, people don't always make that association between that period of stress or illness and that sudden, diffuse loss of hair.

Chris - Is that form of hair loss permanent? Because if you've got the androgen-related hair loss, in male pattern baldness, for example, you're probably not going to get that hair back, are you? But if you go through a period of extreme stress, is that also irreversible, or as soon as the stress subsides, your hair comes back?

Justine - Usually, when that period of stress disappears, then the hair cycle shifts back to a longer anagen cycle and less of a hair drop. But some people can develop what we call chronic telogen effluvium, so it can be ongoing. So it's important to look at those drivers.

Chris - And if I look at my mum and my mum's dad, and I find, oh dear, it looks like the genetic legacy being handed to me is going to be one that I'm going to prematurely bald. Is there anything, as a man, I can do about that?

Justine - Yes, I think there is. I mean, first of all, think about your general health. As I said, diet, stress, certain factors will have an influence on our hair health. That's really important. But also, you might want to intervene a bit earlier on. So you might want to start using something like minoxidil. Minoxidil is used topically and sometimes orally. And this is a medication actually for blood pressure, which vasodilates the vessels. And they found that in their studies on blood pressure, people were getting hair growth. And it seems that minoxidil can help with hair growth and to start to stop some of that process with androgenetic alopecia. You get increased hair growth, so you get back more towards the anagen phase. The hair becomes slightly thicker and you start to reverse some of that miniaturisation of follicles. There are other medications. People can have things like finasteride. That is a drug which blocks the enzyme 5-alpha reductase 1, which pushes testosterone to that active form of dihydrotestosterone, which affects the follicle. So you can use that drug. That is FDA approved, but it can have side effects. Some of them get sexual dysfunction. They can get noticeable breast development. There's even anecdotal discussion around possible lowering of mood. So it is a drug which works, but not without side effects. So you need to be carefully monitored.

15:01 - The history of how hair loss is perceived

The history of how hair loss is perceived

Glen Jankowski, Leeds Beckett University

Whilst the loss of hair is usually no cause for medical concern, the psychological impact of thinning up top can be significant. A survey by Lloyds Pharmacy here in the UK found that only 5% of men were still happy with their hair when they started losing it. But this wasn’t always the case. If we look back throughout history, a great many cultures and ideologies revered baldness, as with it came connotations of wisened experience. That switch seems to have flipped only in the last 150 years. But why? I’ve been speaking with Leeds Beckett University’s Glen Jankowski.

Glen - Some of the earliest forms of what's known as snake oil, which are essentially products that have no efficacy, that don't work, but are sold as miracle cures, were to cure baldness. Those proliferated in the 18th and 19th centuries and they changed how we saw baldness. They stripped it of any positive or neutral connotations, they made it into a disadvantage, a disease, something that needed cure, that needed the product to buy. And then later in the 20th century, mid-20th century, we started to do research and found hormonal and genetic links to baldness, this further confirmed the claim that it's this devastating disease and that hormonal and genetic treatments were necessary to solve it. Even though this research and these claims are flawed, it's not a disease in my view.

Chris - Was there one particular part of the world where that kicked off and then it spread like a sort of social contagion, perhaps around the British Empire, for example, or did everyone kind of begin to move in that direction everywhere, roughly around that time?

Glen - Yeah, you're right. Snake oil was more prevalent in the UK, Europe, especially the British Empire. And we know that these businesses and then later companies that started to produce widespread anti-baldness products like Minoxidil and Rogaine were specifically selecting wealthy white men to buy the products because they had the income that they could sell the products to. And actually the first experiments done on these products were on working-class people, so prisoners in American prisons or men who had been castrated and were in mental asylums.

Chris - What about people taking steps to avoid it or hide it? Does that become much more common as these negative connotations spring up? So as well as snake oil and people attempting chemically to reduce the rate at which they might be losing hair, what about people taking steps to make it look like they're not going bald?

Glen - Yeah, they exist. And to me, it's very hard to separate their own individual distress from the wider culture of advertising, especially that which promotes baldness as such a negative issue. I feel adverts get inside us and change our behaviour. And I believe that's the case for many balding people, including myself. You know, these adverts are very explicit as well. There was an award-winning campaign for a series of anti-baldness adverts that used to feature a hair follicle, basically embodying a human person on the edge of a bridge or a cliff about to jump to its death. And the only thing saving it is the bottle of anti-baldness lotion. And this really promotes the claim that baldness will drive you to suicide, that it is so depressing. And it's very hard for me as a researcher to say that that won't affect the personal experience and interpretation of baldness. Executives and company employees in the billion-dollar transplant industry, for instance, saying we want to grow around the world, baldness affects everyone, we want to expand our markets. And some of them make claims like, you know, we're going to make the world baldness free, or that all people should get hair transplants around the world. So their agenda is quite explicit in reducing the amount of acceptance there is around the world for this.

How modern-day wigs work

Maureen Reynolds, Aderan Trendco

Historically the most common way to cover up hair loss was with a wig. Wigs became a significant fashion statement and a practical solution in Europe from the 17th century onwards, primarily to conceal the symptoms of diseases like syphilis and its associated hair loss, sores, and baldness. Fortunately, modern medicine means we're far more able to treat the underlying diseases behind the need for these wigs, but that isn’t to say, though, that wig advancements haven’t come on in leaps and bounds too. Gone are the days of dodgy toupees blowing away in the wind. Now, we have perfectly sculpted undetectable synthetic specimens. I’ve been hearing more from Maureen Reynolds who works at Aderan Trendco, a company that creates and fits bespoke wigs, and began by asking who these wigs are most suited for…

Maureen - Anybody that's suffering from fine thinning hair, anybody that may be going through chemotherapy, clients that suffer from alopecia, men, women and children who may be experiencing any form of hair loss.

Chris - Do the medical teams refer people to you proactively? As in, “It hasn't happened yet, but it's going to because of some of the things we're going to do to you,” they'll say to the patient, “go and see Maureen.” Or do people tend to come to you once they're already losing their hair?

Maureen - So the medical teams do refer to us, clients from Macmillan, clients from Maggie's, anybody that may be having chemotherapy, they will be referred to Aderan, yes.

Chris - And how do you approach it with them?

Maureen - Always, it's down to consultation. We would never put ourselves in the client's shoes, never, ever, ever. We would ask them lots of questions to gain an understanding of their journey and what they're experiencing.

Chris - But do you get some people, I mean, I think if I was in that position, God forbid, I would think, oh, I don't want to wear a wig. Do you get people who are very resistant, and then actually they say, “in fact, you know what, Maureen, I've changed my mind?”

Maureen - Absolutely. We have lots of patients who come in who have the idea that the wigs are going to look nylon, they're not going to look natural, they're not going to feel like hair. And once we go through the consultation with them, we try different wigs, different systems for them from the information that they give us. Many of them, Chris, they're so shocked and surprised by the results that they actually continue wearing the hair after they've completed their treatment.

Chris - So, if I came to see you and I was in that position, how would you consult with me? How would you come up with a solution for me?

Maureen - So, we would ask you about your lifestyle. We would look at any existing hair that you have at this moment in time. I'm going to look for a perfect colour match for you. I'm going to look for the density being the exact density that your natural hair is at the moment. And I'm going to look at the texture and any curl formation that might be there. From that then, we can recommend systems.

Chris - And are these real human hair, these wigs?

Maureen - They are human hair, they are fibre, and there's a new product on the market that we use called Cyber V.

Chris - And what's that? Is that synthetic?

Maureen - It is synthetic, but it's actually designed so that it has a cuticle, it has a cortex, and it will lie exactly the same as human hair would lie.

Chris - How do you then kind of fit people? Is it a bit like going to Savile Row, and people measure you up and kind of give you a sort of trim here, tuck there? Is it over a sequence of fittings then and you get something people are happy with? Or is it a one-size-fits-all?

Maureen - It's definitely not one-size-fits-all. So depending on your lifestyle - and it's very important at Aderan's that we get that information from you - you may be a swimmer, you might be very athletic, you might want to wear your hair when you're in bed at night, you may not want to take it off. So there are systems such as a system called the CNC, which is a hair replacement system. It's non-surgical, it's very natural-looking, it's very comfortable, it will last 18 months and you come back to the salon every four to six weeks to have it cleansed and refitted. But there are also things like ‘ready-to-wear’, which is a whole collection of wigs, hair pieces, gents’ systems. And you can buy those on the actual day, have them fitted and have them styled.

Chris - How do you keep it in place? Because that's the thing that when I talk to people, including patients, their biggest fear is being de-wigged in public and the embarrassment of that. So how do you make sure that doesn't happen?

Maureen - Your Aderan's consultant does all the fitting for you. It's a very secure attachment. We use medical-grade adhesive or specialist tape and you will come back every four to six weeks for removal, cleansing and then reapplication. The whole thing will actually last you 18 months before you need a new one.

Chris - And if you're not Maureen, who has an eye for this kind of thing, can you tell that it's a prosthetic?

Maureen - You cannot tell. It's what we call an invisible connection. So even the client who's wearing it often forgets they're wearing a piece. They really do.

Chris - Do you know, you've really opened my eyes because I thought I knew a bit about this and I had no idea it was this good or could give people that liberating sense of normality, going about their daily life doing this. That must be so amazing for the patients who want that.

Maureen - It certainly is. It gives them their freedom back, definitely.

Chris - And is that the reaction you get when you see people and you take them on this journey? And incidentally, how long does it take from first meeting you to when they walk out the door a new person? How long has it taken? What is their general reaction?

Maureen - So if they decide that they wanted something that was ready-to-wear, we have over 300 wigs here, over 500 different colours. If it's ready-to-wear, they could actually walk out the door with it on the same day. So from the consultation, through to us fitting, through to us cutting, styling, and then explaining how they care for it, they can take that home on the same day. If you decide you wanted the CNC hair replacement system, you would come back for two or three fittings because we would be doing a digital 3D render of your head. So that's basically us taking the measurements to ensure the precision with the fitting.

How does a hair transplant work?

Asim Shahmalak

While cosmetic solutions can play a crucial role in helping people feel like themselves again, others may choose to explore medical or clinical treatments in the hope of restoring their natural hair. From tried-and-tested medications to emerging clinical procedures, the options can be overwhelming. One procedure that is experiencing a meteoric rise in popularity is the hair transplant, in which patients have hair moved from an area of the head on which it is still growing, to areas that need a bit of a top-up. But what are the benefits and costs of such a procedure? To make sense of what’s out there, I spoke with hair transplant surgeon Asim Shahmalak...

Asim - Hair transplantation means removing the follicles from the back of the head and to insert those hair follicles, also known as grafts, to those areas where people have lost their hair.

Chris - When you move a hair follicle in that way, does it take with it its resistance to being lost? So if you put a hair from the back of your head where you haven't lost hair, to a place where you have lost hair, it doesn't die off like the hair that was there before?

Asim - No, it does not. The reason being, mostly my patients are men, 90% are male patients. And if you see a quite old chap who's maybe 80 or 90 years old, bless him, and he's totally lost his hair. But men always keep a horseshoe area at the back of the head, which is genetically programmed never to be lost in their life, no matter how old they are. So this is known as the safe donor zone. When you remove from that particular part, which is permanent for the rest of their lives, and then put them back wherever they need to be, as I mentioned before - in the scalp or the eyebrows or beard - they will never go.

Chris - And practically, what's actually involved in harvesting a hair follicle from that safe zone at the back of the head so it can be re-implanted somewhere else?

Asim - There's one popular method these days, which is the most advanced technique, known as follicular unit extraction, in short form, also known as FUE. It's performed under local anaesthetic. Patients come in in the morning, shave the area, numb that particular area where hairs need to be removed under local anaesthetic, and remove the hair follicle one by one. And it's very important to know that when you remove the hair follicle, you remove it from its root, because the root will grow, not the hair. And then you remove them one by one and place them into the area where there are no hairs.

Chris - How do you actually get the hair out from the donor zone? Is this through a needle, for example?

Asim - There's a small cylindrical punch, which has a hole in the front, and then it can be done manually. But most of the time, in this day and age, people are doing it via machine. And it depends on the individual's type of hair. If they have very fine hair, you use a very small punch. But if somebody has coarser hair, then you use a larger punch diameter.

Chris - And then to replant that follicle into the more hair-sparse part of the scalp, for example, how do you do that? How do you decide where to put it? And what's the process of actually putting the hair follicle back in its new home?

Asim - Once the hairs have been removed from the back of the scalp, then I numb the forehead and then take a very tiny blade. Again, these blades are very small, ranging from 0.7 millimetres to 1.1 millimetres. After making those holes, the technicians insert the grafts individually one by one into those particular holes.

Chris - And when you follow these people up, what's the survival rate of the transplanted follicles? If you know how many you took out and you know how many you put back in, what fraction would you expect to survive and persist in their new home, say, six months later?

Asim - First of all, let me correct you. It does not grow back in six months. It starts to grow back from six months. And it takes about a year to 18 months to see the full growth and the full result. In general, the success rate for hair transplant is quite high. It's a good 90 to 95%. But of course, no surgical procedures - doesn't matter what they are - come with a guarantee, because how the individual looks after the aftercare at home depends on them. If somebody is a smoker, then there's poor growth or less growth. If somebody has underlying health issues, for example, if they are diabetics. So there are different factors involved in the success rate.

Chris - And it's important to also consider downsides. There's no such thing as a guarantee in any of this sort of thing, especially with any medical intervention. What can go wrong? And how often does that happen?

Asim - Hair transplant, generally, is a very safe procedure. But it depends who is doing it. It's important for your listeners to know that these days, unfortunately, clinics are popping up left, right and centre that are not run by doctors, but by so-called salesmen, and they call themselves consultants. They get the patients and the doctor meets them on the day, says hi and hello, then hands them over to these untrained, unqualified, non-medical people known as technicians. And then they start doing these hair transplants, thinking it is very safe for them to do. In their hands, unfortunately, there's a high level of complications. Unqualified people can over-harvest, remove a lot of hair follicles from the back of the head and hence damage the donor area for the rest of that person's life. Again, if they are making the incisions, the sites, the holes in the front where the recipient areas are, and they are not using the proper solution to numb the area, they can cause what we call skin necrosis or blackening of the skin, which is quite damaging. And then you have to undergo a major surgery to remove that particular part. So it's quite important that listeners, when choosing, make sure it's the doctor, the surgeon, who is properly qualified, experienced and trained, who is doing the surgery.

Chris - Are you seeing a big demand for this? And has that changed?

Asim - Absolutely. I've been doing hair transplants for the last 22 years. And it's a drastic change in the industry because of so many new techniques and new tools and new punches involved. And more importantly, it's becoming more and more affordable as well, and achieving very good results because the technology has really advanced. It's now acceptable. There used to be a taboo attached nearly 10 or 15 years ago, but not anymore. And those high-profile people - TV presenters or film actors or footballers - they are coming out and having a hair transplant and going public with that. So this has really helped a normal person to accept that yes, it is acceptable to do a hair transplant, and you can achieve better results, good results, without much embarrassment about it.

Comments

Add a comment