The Census of Marine Life - Celebrating a decade of discoveries

In a special edition of Naked Oceans we celebrate the world's first Census of Marine Life as it draws to a climax this month after ten years of amazing ocean discoveries. Recorded at the Census conference at the Royal Institution in London on October 4th 2010, we meet many of the people behind the census, find out how the whole grand project got going, and pick out some of the census highlights. We also hear some musical inspiration from the census and chat with distinguished oceans explorer, Sylvia Earle.

In this episode

00:11 - Highlights from world's first ocean census

Highlights from world's first ocean census

with Paul Snelgrove, Boris Worm, Ian Pioner, Enric Sala

We hear from four top scientists from the Census of Marine Life about what for them were the highlights of the collosal ten-year survey of the oceans.

Find out more:

First Census of Marine Life - Highlights of a decade of discovery

Paul Snelgrove's book:

Discoveries of the Census of Marine Life. Making the Oceans Count.

Paul Snelgrove, Memorial University of Newfoundland

Ian Poiner, Australian Institute of Marine Sciences

Boris Worm, Dalhousie University

Enric Sala, National Geographic

Paul - I would say that the really big discovery is that the age for discovery for ocean life is right now. And everywhere we look from the shoreline to the abyss we find a plethora of life. In the areas we know relatively well we have t o look a little harder but we still find new species, new migration routes, new relationships. But then in the environments we don't know so well, almost every sample we bring up contains new species scientists have never seen before.

There's a tremendous opportunity for discovery. There have been some 1200 new species described over the ten years of the Census. And we believe we have another 5000 sitting in jars species awaiting description.

And the really exciting thing is that for every species we know about, there are at least 3 or 4 we don't know about. So the 250,000 known species in the ocean probably is just a quarter of what's actually out there and possibly more. And that doesn't even include the microbes which are extremely diverse.

I would also point out that the oceans are changing very rapidly. There's a lot of bad news stories about the oceans, there's no doubt about it. But I think there's also cause for great hope because there is a plethora of life and so much to discover.

Boris - In my view the most stunning outcome of the Census is to transform, fundamentally transform, our view of the ocean as a place that is much more species rich, much more globally connected and much more heavily impacted than we had thought.

And you know, when I sat here and looked at all of you, I thought that's us as a community as well. We are much more rich, species rich, much more globally connected today, and we have much greater impact that we ever had thought on the way people perceive the oceans.

Ian - One of the most important things about this first Census of Marine Life is we've demonstrated it could be done. By doing it we've created a benchmark, a benchmark that will serve science and society for many years to come.

The Census was an unprecedented example of global cooperation. When we started in 2000 many people were quite sceptical about whether we could achieve this but we overcame that scepticism to complete the first census.

Enric - This project has completely transformed our vision of the ocean. So right now we know there are far more species than we thought, that ocean life is more connected than we thought but also that it is more impacted by human activities than we thought 10 years ago.

Helen - Can you pick out a few highlights of things that you thought - that's awesome.

Enric - Yes, there is much more life in the ocean than we expected. During the last 10 years we've been able to find about 6000 new species during the Census. But now we know based on all the studies and all the technologies used in the Census, that before we had about 250,000 species known in the ocean, now we estimate that there at least a million species in the ocean of larger things. If we think about microbes we may be talking about a billion different species in the ocean. This is something we couldn't have imagined before the Census. For me that's one of the main highlights.

Helen - Why is it important to know how many species there are? Maybe they will have all gone by the time we find them and name them?

Enric - There are so many species on the planet. And we might not even know how many species are there, with precision. And probably we will never know what all these species do in the ecosystem. However, they all have a role and we are living in an interconnected planet. So, imagine you were to board a plane and the flight attendant told you that 10 screws were missing from the plane. And you didn't know what those screws were for, you didn't know their function. Would you board that plane?

We are removing species, species are going extinct and we don't know what they do. We might be compromising the ability of the ocean to give us all these services that are essential for us like oxygen, regulation of the climate, coastal protection, food, medicine. All these things that we take for granted. And by impacting the ocean as we have been for hundreds of years we are reducing the ability of the ocean to give us all those things that make our planet such a wonderful place to live.

Helen - How about your involvement in the Census, and your own research and the areas you've been looking at. What kind of things have you been doing towards this grand project?

Enric - I was associated with the history of marine animals populations program, which looked at human impacts in the past using historical and archaeological data.

Also, I've been conducting a series of expeditions to the last pristine places in the ocean, the last virgin places. These places are like time machines that show us what the ocean was like before we started degrading it. So these places are the last baselines left.

Helen - Where are they?

Enric - There are a few places left in the polar seas, in the Arctic and the Antarctic, and in remote uninhabited archipelagos in the middle of the oceans especially in the Pacific.

Helen - That sounds like a wonderful place to visit. That must have been a very life-changing, eye-opening experience to be able to go to those very remote places and see what life might have been like everywhere, I guess, in the past.

Enric - Absolutely. Going to these pristine places has been the best thing I've ever done in my career.

Imagine you're an alien, you come to earth to study how cars work. The first time you land, you land in a junk yard. And you study one of these wrecks, a car wreck. It's all rusty, the engine doesn't work. The wheels are gone but the battery still has some juice. So you push a button and the windscreen wipers move. So you may well conclude that the car is something that allows you to sit comfortably inside, even when it rains you can see the landscape because these things clear the windscreen.

If you really want to know what the car does, you should go to a dealership and study a brand new car. Most of the ocean that has been studies in the last 50 years with scuba diving are like junk yards, we are studying wrecks. Ecosystems that have been degraded, where essential parts are missing, where species are gone. These last pristine places are like the dealerships of the ocean, places where we can read the instruction manual of how ecosystems work. These places will allow us to understand the true magnitude of our impact in the ocean but also to have a baseline for conservation, to decide what we want for the future.

Helen - And how about the future for the Census. Do you want to see another Census?

Enric - I think the Census is a first global baseline. There will be many more studies building up on this global framework, global community. Even if it's not called the Census of Marine Life 2, the legacy of the Census is going to last for decades.

10:14 - How the Census of Marine Life began

How the Census of Marine Life began

with Jesse Ausabel, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Rockerfeller University

Co-founder of the Census of Marine Life, Jesse Ausabel, tells us about a very big idea he had a little over ten years ago, and how he and colleague Fred Grassle set in motion the world's biggest survey of the marine realm.

Find out more:

Jesse Ausabel at

Rockerfeller University and at the

Alfred P. Sloan Foundation

Transcript:

Jesse - On July 2 1996 a deep sea expert named Fred Grassle, walked into my office and said "I think something big needs to be done for marine life, for marine biodiversity". He said that's obviously because of overfishing and pollution but also because so much remains to be discovered. He had published an estimate that there may be between 1 and 10 million forms of marine life.

So I said, "Fred, give me a list of what is actually known today". He was embarrassed and said, "I can't give you a list, we don't have one."

And I said, but people have been studying marine biology since Aristotle, for 2500 years. How can you not have a list, there must be a text book with a list of all the forms of marine life. And he said, "Well, the sponge people have their lists, but they don't always agree with the corals people, and they don't talk to the anchovy people, and the anchovy people don't like the tuna people, and the tuna people don't like the shark people because sharks sometimes attack tuna."

So he said, there's a lot of information but it's just not organized and most of the ocean is unexplored. So we talked for about 1.5 hours and at the end of the 1.5 hours we had the idea to have a big observational program in which we'd have hundreds of expeditions and really try to get better real information and observations.

Fred also had the basic idea, he said "We have to have a common database, so the anchovy people, and the sea star people and the herring people can't all just go off in different directions. But we really want to know everything."

So we both thought the idea was wonderful. We went off in separate directions and starting talking to our colleagues about it. Most people said the idea is wonderful, and most people said the idea is crazy. Some of them said it's romantic, some of them said it's impossible. But no one said don't try to do it. It made people somehow smile or laugh that we wanted to count all the fish in the sea.

So we had three whole years of feasibility studies, between 1997,1998 and 1999. So we did do our homework. We had lots of consultations. We wanted to make sure the technology was powerful enough. We wanted to make sure that people would cooperate. We wanted to make sure that if we did finish, as we have now done, people would feel it was worthwhile.

So we had three years of feasibility studies, at the end of which more people thought it was a great idea and some people still thought it was crazy. But fortunately, the people with the chequebook, the Sloan Foundation, said well lets take risks - that's why we're here. We're not a federal government agency we should take a chance on something. And the president and the trustees of the Sloan Foundation said "we will support this program for 10 years as long as it meets certain milestones".

And that's very important because if you talk to lots of naked scientists you'll know it's difficult to get clothing for more than 1, 2 years at a time. It's very hard to get long term commitments, so the fact that one organization, even though it couldn't provide all the money in the end it provided 12% of the money But it said, "We will be steady. We'll provide basic support every year so you all can talk to each other, coordinate, make your plans. And if you do well, we'll keep supporting you until you finish in 2010."

So in 2000 we started organizing. Fred's view was that we should get in the water quickly. We'd already had some years of feasibility studies and he said "In many programs you write a plan, then you write a plan to write a plan to write a plan. And people spend 10 years planning and never get in the water or launch the rocket."

Fred said "Let's start doing thing right away showing the kinds of things we think should be done then try to attract people to the project by example rather than by inviting people to write documents."

So we started right away in 2000-2001 with some expeditions in which we tried to show that we were interested not only in the squid, but we were interested in what lived on the bottom, we were interested in seabirds and all the different forms of marine life. And people became enthusiastic. IN the end almost everyone participated even though we never went out and dragged people in. It was a kind of voluntary Noah's ark. So the abyssal plains people and the seamount people and the coral reefs people started to come to us and say " We want to be part of this".

It grew and by 2004-2005 we basically had all the different habitats and species represented.

Helen - And I can see by the grin on our face that it's clearly a wonderful experience for you to be here, stood here, 10 years down the line with your crazy, romantic, impossible project finished.

Jesse - It's been the best experience of my professional career, maybe the best experience of my life. I feel a little bit like an Olympic diver who chose a very hard dive. You do the triple somersault and it worked. So I have a little bit of that feeling today. I'm very proud, also because what we've done is important. It's not easy being a fish these days and we should be a lot more sensitive about how we treat life in the oceans.

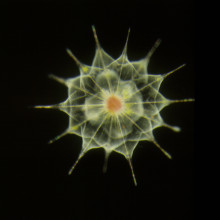

16:24 - Barcode of Marine Life

Barcode of Marine Life

with Ann Bucklin, University of Conneticut

With many millions of specimens collected by scientists from the Census of Marine Life over the last decade, the task of identifying them all to species level is still a long way out of reach. But powerful genetic tools have been developed that help catalogue ocean diversity much more quickly than is possible with traditional taxonomy.

Find out more:

Ann Bucklin, University of Conneticut

Census of Marine Zooplankton

Marine barcoding

Consortium for the Barcode of Life

Transcript:

Ann - We would love to name everything in the ocean. We have a team of expert taxonomists in every team whose job it is to name species. We've found hundreds of new species, we're in the process of naming them, we think it's the right thing to do.

The problem is that naming species with formal taxonomic descriptions is a very slow process. And so many of us feel that we just don't have the time. So the next best thing that we can offer is some kind of objective, reliable, valid indicator of what a species is.

What the Census has done is say that we have a reliable marker of species that we call a DNA barcode. And that's a short sequence and we know that it doesn't contain all the information that we know morphologists would like us to have. But we also know that it's a really good indicator of what a species is and is not.

And so the goal of the Census barcoders is to provide a set of data which can be translated eventually, when we get to it, into species. The wonder of barcodes - there are some dynamics of DNA sequences that are quite remarkable and extremely helpful in this endeavour. One of them, in all cases the DNA sequence variation is less within a species than between a species. That's called a barcode gap. Barcodes are good to identify species.

Another one is that barcodes do a very good job of clustering major groups of animals. You may not know what species it is but you know which group it belongs to. And so with barcodes you can get a kind of an index of biodiversity. It isn't the same as naming species but it actually is going to help us conserve them.

Sarah - Ann, how do you go about barcoding? Do you take a scoop of sediment and work out, right, there's this many types of nematode worm, there's this many types of mollusc in this sample.

Ann - The way the Census has started barcoding is what we call "gold standard barcoding". And so we work from an identified specimen. A taxonomist says this is the species and that taxonomist gives the specimen to the barcoders and we determine a sequence. And so now we have a gold standard. We have a DNA sequence with a name on it. And so overall, 35,000 species of marine organisms, marine animals, have been barcoded.

Now, what we're starting to do is to take that scoop of animals, whether it's a net sample of plankton, a scoop of sediment, any type of habitat that you could name and we're doing deep sequencing with a new high through-put sequencing.

What we do then is a very complicated analytical task, which is done for us by bioinformatics, to tell us how many species we think are in that sample. Some of those will match our library of gold standard barcodes, some will not. But some will be close enough so that we can classify. So we can say, we don't know what copepod that is but we know it's a copepod. So that's the power of what we call environmental barcoding.

Sarah - So how important do you think barcoding has been within the Census. How important a role has it played within it?

Ann - The Census has embraced barcoding across all the 14 field projects. There's a partner program to the Census that's called the Consortium of the Barcode of Life. And the Consortium of the Barcode of Life has a campaign for marine species that started in 2004 and we've worked very closely together. Some of the Census projects have partnered with the Consortium of the Barcode of Life, some of them have done it themselves.

But very early on in the Census, all of the projects were asked to designate a person, a laboratory, to learn the standardized techniques of the Consortium of the Barcode of Life, all of the data quality requirements.

So what we have now, of course, is a situation where the sum is great, much greater, than it's parts because we actually have data from all the Census projects that are entirely comparable, carried out using the same protocol, the same approach, the same gene, so we are looking at a library of barcodes now that is going to be a baseline for us to both to continue the gold standard barcoding effort and also use environmental barcoding to do this kind of index. We call it a genomic signature, a genomic fingerprint so that each ocean realm can have a different genomic fingerprint characterised by barcode diversity. It's not the same as knowing species diversity, but it's close.

22:52 - The importance of tracking

The importance of tracking

with Pat Halpin, Duke University

As well as venturing out to discover as many different forms of ocean life as possible, the Census of Marine Life also undertook the task of discovering more about how animals move around and use the oceans, to feed, mate, and spawn. Using various tracking techniques, Census scientists got insight into the lives of many of the oceans' mobile inhabitants.

Find out more:

Pat Halpin

OBIS-SEAMAP (Ocean Biogeographic Information System Spatial Ecological Analysis of Megavertebrate Populations)

Census of Marine Life Mapping & Visualization

Pat - Tracking is incredibly important because we're trying to find where the animals actually use the habitat. So if you just went to someone's house but you didn't ask them where they went during the day, you would just know their address.

What we're trying to find out is where do the animals actually go. Some of the animals traverse the entire ocean.

We had a whale that we tagged in Antarctica in 2009 and it showed up in American Samoa.

And so you start to find out where the animals actually move in the oceans, what part of the oceans do they use. You locate an animal one time you may get just 1% of their actual habitat.

Sarah - so I guess it's just a snap shot of their entire life and how they live. And I suppose it gives you a clue as to how the ecology and their interactions with other species and other organisms and other habitats?

Pat - Correct. You get a snap shot, it might just be one moment in their life, it might be just representing one week in their life. And we really need to explain why do they move different places, what are the most important places.

I do a lot of work trying to translate the science into policy. And we need to know what is the management regime we need to have to actually manage these animals. Having a snap shot just doesn't do that.

Sarah - How can the tracking help to inform the conservation of these animals?

Pat - When we're tracking animals we're finding out not just where they are but what they're doing. So we find out, are they feeding in one place, are they migrating to another place to spawn?

So we know why it's important. We might find out that the spawning areas are incredibly important to protect and other places that are migratory corridors. We'll have a different perspective on how to manage these places.

Sarah - So I guess it's a little bit like having the corridors between various areas of biodiversity like in a rainforest so you have two areas that are protected but you need a corridor between them that's also protected in order for the species to migrate between then otherwise you'll end up with isolated populations and endanger those species?

Pat - Exactly. What we need to be able to do is to define why they are using different habitats and explain the corridors and connections between them. We actually use a lot of network analysis in order to be able to understand the connections, exactly the same kind of analysis people use for social networks, for transportation networks, to try and find out what are the important connections. So, it's the exact same thing with marine species.

25:49 - Protecting the oceans

Protecting the oceans

with Kristina Gjerde, IUCN

The Census of Marine Life isn't only about the science of gathering and naming species and tracking them through space and time, it also has a vital part to play in helping to protect the oceans.

We caught up with maritime lawyer Kristina Gjerde, a conservation advisor for the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) about how we can best make use of all the data collected by the Census.

Find out more:

Global Ocean Biodiversity Initiative

Transcript:

Kristina - Bringing the high seas, the oceans, into the living room of the public will help to stir some concern about what is the state of the oceans these days. And if that concern can be translated to the policy makers, that's in the capitals, in our home towns, then we'd start to see some action.

We need more protected areas, we need tighter restrictions on fishing, we need new levels of accountability, responsibility. We have more power to go out and do new things in the marine environment, we also need an accompanying parental restraint so we don't do everything we can but, as they were saying, we need the car with the seat belts before we go out to sea.

26:58 - Creative inspirations from the census

Creative inspirations from the census

with Jesse Ausabel, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Rockerfeller University

As well as all the scientific endevours of the Census of Marine Life, artists and musicians also got involved and shared their love of the seas.

Census co-founder, Jesse Ausabel, tells us about the creative side of the program and we hear an excerpt of Look to the Sea - a song composed and recorded especially for the Census by singer/composer Maryann Camilleri, musician Jerry Harrison (formerly of the Talking Heads), and engineer David Dennison. The accompanying video is by produced by National Geographic Television/Digital Studio.

Find out more:

Listen to and download

Look to the Sea for free.

Maryann Camilleri

Census of Marine Life and the arts

Transcript:

Jesse - This is another funny thing that happened. About 2 years ago we were having a meeting in California in the Monterey Bay area. And an acoustician who used to work for me but now works in Berkley California said "Oh I have some friends who are musicians but they love marine life so is it alright if they down to the meeting in Monterey?"

So I said "Sure, bring them along." They turned out to be musicians from the Grateful Dead music scene. And they loved all the fish that they met. One of them, a woman named Maryann Camilleri said "Can I write a song about it?", so I said of course you can write a song about it.

So she wrote a wonderful song which has been recorded at the Grateful Dead recording studio with lead keyboard by Jerry Harrison, form the band Talking Heads. You're a bit young so you may only be into Belle and Sebastian or newer people. It would have been great to get Radiohead or Greenday. I'm older so I though getting Talking Heads and the Grateful Dead was just great.

So we have this wonderful song, music video, really good song Look to the Sea, which you can download for free, you don't even have to pay in the US 99 cents for the mp3

And artists donated pennants, and made sculptures and paintings. All this stuff just sort of happened. And I think it's because marine life is beautiful. I think beauty was the attractor.

29:28 - Winding back the ocean clock

Winding back the ocean clock

with Poul Holm, Trinity College Dublin

As well as exploring the oceans for present-day marine life, the Census of Marine Life has also been using innovative ways of winding back the clock to build a picture of what the oceans used to be like and the impact humans have had on them. We talk to Poul Holm about how the Census has been recreating past oceans and how this can help us plan for the future.

Find out more:

History of Marine Animal Populations (HMAP)

James Barrett et al (2004) The origins of intensive marine fishing in medieval Europe: the English evidence. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B (PDF)

Poul - Ten years ago my colleagues said to me writing the history of the oceans - you can't do that because we don't have the sources. Historians don't do fish. What we now know is that we have actually go plenty of evidence for now much we've taken out of the oceans, what kind of footprint that has left.

We also know a bit about how that impacted the development of human society. So it's learning more about our relationships with the oceans. I think that's exciting because so little work has been done in that field.

Helen - And you're looking into the past. How do you do that, and how far are you able to look back into the past now, when it comes to oceans and fisheries and so on?

Poul - well you need to look into all sorts of sources. It can be, well obviously, written records. As a historian I would go to port books, I would go to skippers' log books, I would go to monastic records. You can go to archaeological evidence, you can look at trash heaps as the Americans would say, or the kitchen middens and look at old fish bones. We can look at sediment layers in the ocean bed.

Some of the most imaginative uses of records was the use of restaurant menus. The New York city library had one, possibly slightly insane collector, who had been collecting restaurant menus and had build up this fantastic series of a hundred years of restaurant menus, which provides a fantastic record of what people used to eat and how we've been eating down the food web. A hundred years ago abalone would be on the menu whereas today that would be an endangered species.

One of the exciting things about this is actually when you use that kind of evidence you will also use evidence that people will be able to relate to very easily. When I talk to fishing communities very often they will flatly deny that they've had any footprint in the oceans. They say, well the fishes are doing alright.

But if I tell them, actually if I look into your grandparents log books they were catching fish that would be three times as long as the cod that you're landing today. That seems to be an indication of some change and they will actually have to say, yeah, that's pretty bad news.

Helen - so it sounds like that during the Census you unleashed this new way of looking into the past. You said that people thought, well how can you do that, and now there are all these creative and imaginative approaches. That's really quite new isn't it, that now you've almost unleashed this whole new field of research?

Poul - Yeah, and the exciting thing is that because so few people have been looking at this in the past there's lots to discover. I think one of the most amazing things is the discovery by James Barret and his group in Cambridge of the so-called fish horizon. We now know that around 1050 - 1100 fishermen all around the north sea, in England, Scotland, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, were going much further out into the open sea and catching fish at depths of two-three hundred metres, bringing back gadoids of all sorts so cod, ling, that sort of species and marketing the fish fairly deep inland. That's new. It really reveals that there was a tremendous change in the diet of ordinary people.]

It explains a lot about the impact that we humans have had on the open ocean because everywhere we look the first thing you do is take out the big fish, the big marine mammals or the big fish. And of course, when we look at the cod bone way back then, these were humungous creatures that they were landing, because no one had been fishing them before so they lived their full natural age of 20 years. They could grow well in excess of 1.5m.

Helen - Presumably we use this looking into the past to think about the present, and even the future? How does your research help us think about things like conservation and what we really need to be doing to the oceans now? It's all very well to say in the 12th century we changed our diets. How does that now help us to look into the future?

Poul - It's kind of sad to know we took out all of that, but it's also something we can turn to really inform us for future ocean policy because if it used to be out there it would actually be rebuilt. Because the oceans are very resilient. Although we have wiped out many of the commercial fish stocks , it's not that the fish have gone in a biological sense. They're still out there. They're waiting for their chance. The oceans are deep and there are many places to hide. So there's a huge potential for us to rebuild fish stocks in the future.

Remember, all the fisheries biology science really rests of knowledge that's been accumulated in the past fifty years. Whereas what we're looking at is how did the oceans look 100, 200, 300 years ago. They were very different, they could be rebuilt to that stage if we want to. Of course that's a political question, will we want to do it? But the economic gains would be sizeable. It would mean there would be plenty more fish and it would be fish of a much more valuable nature.

Because of course if you have a fish which is allowed to grow to longer scales you actually have much more attractive fisheries. And you will also have much more resilient fisheries because it makes no sense now that we killing off cod at the age of less than three years of age that's just before they spawn for the first time.

It would make more sense to wait until they are at least 8 or 10 years, have spawned a few times, and actually we know that the eggs of cod that have spawned a few times is actually much more likely to survive all the hazards that confront a little fish egg. So, lots of gains to be made, and we can learn that from history that the oceans will actually provide that future for us, if we want to. It's not doom and gloom it's actually tremendous potential.

37:03 - Sylvia Earle's message

Sylvia Earle's message

with Sylvia Earle

A pioneer of deep sea exploration, Sylvia Earle has spent thousands of hours underwater and still holds the record for walking on the seabed deeper than any one else - in 1979 and she walked around 400 metres beneath the waves in a metal suit called "Jim". She has devoted her life to exploring and protecting the oceans - in 2009 she won the TED prize with her proposal to set up a global network of marine protected areas, what she calls "hope spots".

We asked her for her thoughts on the Census of Marine Life's achievements.

Find out more:

The SEAlliance

Transcript:

Sylvia - It's been said several times and I'll say it again, this is a wonderful beginning. Ten years is a long time, and it's set the stage for whatever follows

This really has stirred things up and makes it perfectly obvious that a great era, perhaps the greatest era of exploration is truly just beginning.

Some think it's all over and that we need to reach skywards for new frontiers, and we can find them there, and we need to do that. But mostly we need to do get to know this part of the university, this part of the solar system, this place that keeps us alive.

It's critical for that great dream of human kind and that is to have peace. We cannot have peace among ourselves if we fail to make peace with nature. And we're not. Right now we're not. We're cutting forests that have been growing for thousands of years. We're mining the oceans of its wildlife that has been developing for hundreds of millions of years.

And I can forgive it only on the basis that people just don't know. They don't know. And yet we have the power of knowing and the Census of Marine Life has gone a long way toward putting things in perspective, that not only have we just begun to get to know this ocean planet and to appreciate that our lives are dependent on the oceans and the creatures.

It's not just rocks and water out there. It's a living system that gives us oxygen, that grabs the carbon out of the atmosphere. That drives the food cycle, and not just the carbon cycle and the oxygen cycle but the water cycle - it's where 97% of the water on the planet is.

And without the ocean: no rain, no water, no life. We absolutely are dependent. We are sea creatures every bit as much as those magnificent umbers of individuals that the Census of Marine life has been cataloguing and celebrating at this occasion.

39:51 - What the future holds

What the future holds

with Paul Snelgrove, Boris Worm, Enric Sala

Now that the landmark, decade-long Census of Marine Life has drawn to a conclusion, the big question is "What next?" both for the census and for the oceans themselves. We hear again from three key scientists involved with the Census to get their thoughts on what the future holds.

Paul - I think one of the key things we've done with the Census is to identify some of the key unknowns. And perhaps equally as importantly, Nancy Knowlton my colleague, used the analogy of flashlights in a dark house. So we have flashlights now where we've looked around a lot of the house and we know where many things are but we haven't really turned on the lights yet.

But with these technologies we really have the capacity to move forward on that ground. And again we know what some of the key gaps are. And so we can move forward. But, I would say that many of us need to catch our breath and so we need to digest what we have and then plan how to move forward because there is still lots of discovery ahead.

Boris - How will the future look like? It will be different. It will be different from what we have collectively documented and detailed in the first Census of Marine Life. This will be a baseline against which rapid future change will be measured.

There's two scenarios that I'd like to contrast. One is a world, or a place where the intensity of fishing, the spread of habitat destruction and the velocity of climate change is increasing the rate of biodiversity los that we are already observing today. Where this will happen we will see a reduction in biodiversity along with the services that this biodiversity provides such as our food supply, water quality, and other economic opportunities that we still have to discover.

On the other side, where we're investing with a concerted effort into rebuilding and managing measures that allow biodiversity to flourish again, for example in protected areas or through wise fisheries management we do see biodiversity increase again and with it the services it provides.

So this is not a scientist's pipedream. This is something we have already documented happening as far back as a hundred years ago but also today at an increasing pace we are trying to take care of what is left and rebuild what we have lost.

Enric - I define myself as an angry optimist. If I weren't optimistic, I couldn't do what I do. There are bright spots there that we can replicate. There are marine protected areas that we set aside, where marine life comes back and then the fish reproduce and replenish nearby areas, helping fisheries, bringing dollars to the local economy through tourism. Most of the species are still there, some are in very low numbers, but they are still there so we still have a chance.

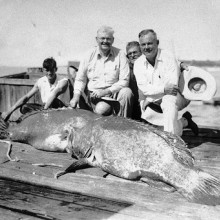

43:04 - Critter of the Month - Sea Urchin

Critter of the Month - Sea Urchin

with Carl Gustaf Lundin, IUCN Global Marine Programme

The spiny denizens of the deep, sea urchins, feature as our critter of the month...

Carl - My name is Carl Gustaf Lundin and I work for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. And if I were a marine species I would be a sea urchin.

I think the sea urchins drew my attention when I was a really young boy and I helped my father to collect samples in various oceans around the world. He was doing genetic research and as you might know sea urchins go through these larval stages, which are quite dramatic. At one point for example they look like Eifel Towers. So I found this fascinating as a boy, and I helped him to grow them in aquaria and it was one of these things where I always felt akin to the ocean very early on.

I guess it was also my first marine event as a professional was as in Monaco. I was sent there and with Princess Stefanie we were eating these sea urchin spreads and I was thinking, okay well I could relate to sea urchins. So there you are.

Comments

Add a comment