Naked Oceans ventures into the deep to find out how scientists are using cutting edge technologies to explore the darkest and most mysterious parts of the oceans. Sarah visits Scripps Institution of Oceanography and finds out how microbes cope with extreme life in the deep sea. And she got to play with some high-tech gadgets that bring samples back from the deep. We also find out find how researchers around the world are joining forces using the latest online social media tools to explore unchartered waters a long way down beneath the waves. And we meet an extraordinary bone-munching worm in Critter of the Month.

In this episode

01:40 - Protect one third of British seas, say conservationists

Protect one third of British seas, say conservationists

Helen - This month there's news about a group of top marine conservation groups - who call themselves the Marine Reserves Coalition - who are sending a strong message to the British government that they need to be doing a lot more to protect the oceans. Here's Alistair Gammell, Director of the UK Office of the Pew Environment Group, one of the members of the Marine Reserves Coalition.

who call themselves the Marine Reserves Coalition - who are sending a strong message to the British government that they need to be doing a lot more to protect the oceans. Here's Alistair Gammell, Director of the UK Office of the Pew Environment Group, one of the members of the Marine Reserves Coalition.

Alistair - The UK controls the seas not only around the United Kingdom but we have these overseas territories, so that actually the UK is one of the major marine nations of the world. I think it's something like 6000 square km that we control. So we can do something really important in the world.

Helen - And what are we aiming at? What do you think we need to achieve with protecting the seas within marine reserves?

Alistair - We're aiming at 30 per cent would be no-take, which sounds a lot, but that still leaves 70 per cent, by far the majority, for fisheries and exploitation and various things, but 30 per cent. But that is so massive compared with what we have round the United Kingdom. We have less than 1 per cent and it's such a tiny little area. There are only three small reserves in the seas around the United Kingdom. But we could do some much more, and we need to do so much more.

Helen - Any thoughts on how we go about doing that?

Alistair - Well, we have to get the public on our side. So we all know on land about things like the Serengeti, Yellowstone park, and we always think Wow those are fantastic, and we should protect them. We need that same mentality in the sea and say actually lets set aside some places as a major public asset and we need to convince politicians to do that.

Helen - I personally think it's really encouraging that people are standing up and loudly pointing out how important it is that we protect lots of the oceans - and that it can be a win-win situation both for fisheries and for protecting marinelife.

You could argue that campaigning for one third protection of the oceans could scare off a lot of people, and perhaps there's not a lot of chance of this ever actually happening and that this is a target that's never going to be reached.

This marine manifesto for protecting a third of british seas was launched as part of a big campaign being run by the department store Selfridges in London called Project Ocean, which is raising awareness about problems in the sea, and raising money to set up protected areas. I think it's a great project because it should get some important messages through to people who might not otherwise really get involved in issues like these - Selfridges is a fairly posh expensive department store, visited by people who have plenty of money to make choices to do things like buy sustainably caught fish.

Well, one place that could help take a major step towards protecting one third of British waters, is the overseas territory of Bermuda. This island in the western Atlantic lies alongside the Sargasso Sea, which is a unique ecosystem based around enormous floating mats of Sargassum seaweed that offer food and shelter for all sorts of other important marine life.

I caught up with Frederick Ming, Director of the Bermuda Government's Department of Environmental Protection to find to out about some exciting plans that are underway for conserving a large part of the Sargasso Sea.

Frederick - There are actually two things happening simultaneously and that's what makes this extremely exciting. We've got one project that would begin at the outer margin of our 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone and work inward from there to create a no-take marine reserve. So, one project is looking inward from the outside. The other, the Sargasso Sea Alliance is looking from that 200 mile zone outward.

Now, the reason why these two are interestingly connected is that we believe that if Bermuda would set the example of setting aside a significant portion of its EEZ, as a marine reserve it would give us the moral authority to be able to invite other countries to take some kind of action, serious marine conservation action.

Helen - Well, it's certainly encouraging that countries like Bermuda are taking marine protection very seriously and let's hope they can indeed set a good example for everybody else.

Find out more

Sargasso Sea Alliance

Project Ocean

06:26 - Giant Fossil 'Strange Shrimp' Found

Giant Fossil 'Strange Shrimp' Found

A Nature paper reveals an exciting fossil story that shows some very strange extinct marine invertebrates called anomalocaridids were around for a lot longer than we previously thought...

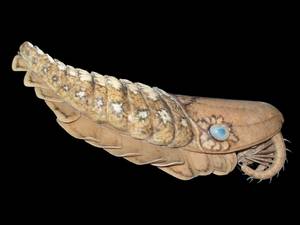

Anomalocaridids look a bit like a cross between a cuttlefish and a woodlouse - with a long segmented trunk, flat swimming 'lobes' running down their sides, two segmented appendages on the front that look a bit like prawn tails, and a circular mouth on the underside of the head that looks like a pineapple ring. In fact, each of these separate elements - the body, the appendages and the mouth, were once thought to be from three completely separate animals. It was only in the 1980s when the late great Harry Whittington, and Derek Briggs (one of the authors on this paper) found complete specimens with all three of these features present, in the Burgess Shale in Canada, and realised they were actually part of one organism, which they christened Anomalocaris. They were very agile, formidable predators of the oceans, moving by undulating their lobes a bit like a ray or a cuttlefish, and crushing prey in their hard circular mouthpiece.

Anomalocaridids look a bit like a cross between a cuttlefish and a woodlouse - with a long segmented trunk, flat swimming 'lobes' running down their sides, two segmented appendages on the front that look a bit like prawn tails, and a circular mouth on the underside of the head that looks like a pineapple ring. In fact, each of these separate elements - the body, the appendages and the mouth, were once thought to be from three completely separate animals. It was only in the 1980s when the late great Harry Whittington, and Derek Briggs (one of the authors on this paper) found complete specimens with all three of these features present, in the Burgess Shale in Canada, and realised they were actually part of one organism, which they christened Anomalocaris. They were very agile, formidable predators of the oceans, moving by undulating their lobes a bit like a ray or a cuttlefish, and crushing prey in their hard circular mouthpiece.

There are four other genera of anomalocaridids as well as Anomalocaris and they're found in Early and Middle Cambrian sites ( so from around 542-501 million years ago) from the United States, Australia, Russia, Poland and China.

This paper, published in Nature by Peter Van Roy, and Derek Briggs, describes new specimens of anomalocaridids from the Fezouata Biota in southeastern Morocco, which is from the early Ordovician Period around 488-472 million years ago. These represent the youngest examples of anomalocaridids by about 30 million years, and provide a link to the great-appendage arthropod Schinderhannes from the Early Devonian.

The specimens they found were large as anomalocaridids go too - some up to a metre long, and they were found within a rich mix of other species - showing that they were still an important part of the marine ecosystem at this time.

Another key finding is the dorsal blades - flat structures found all the way down the back of the specimens. These were one thought to be scales, but here the authors suggest they may have performed some sort of respiratory function, possibly because of the high oxygen requirement of an active swimming lifestyle.

These new Moroccan specimens are the youngest examples (in geological terms) of anomalocaridids yet found and the authors suggest that they may have died out after the diversification of other groups like predatory eurypterids - huge sea scorpions - and cephalopods during the Ordovician.

24:31 - Social networking tools help deep sea explorers

Social networking tools help deep sea explorers

with Tim Shank, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Pioneering exploration of Indonesia's deep sea uses latest social networking tools to link up a virtual global laboratory.

Tim - In this case we were doing something really novel. We had a remotely operated vehicle, so we had a robot that had a very good high definition camera system. We were doing pure exploration of the seafloor.

No one had ever been to this area of Indonesia, north of Indonesia in the Sulawesi Sea. The vehicle wasn't novel in itself but the signal that was coming off the seafloor was transported around the world. There were scientists in Indonesia and various parts of the US, in Europe, in the UK, that were all tuning in at the same time. We have Skype and iChat going.

And as we saw live pictures coming in we could hear the pilots of the ROV onboard the ship, we could hear everybody on the ship we wanted to and we could communicate with everyone who was listening in. We had also conference calls going on at the same time. So we had voice, we had iChat, we had Skype. So that to me was a real first. And so we were able to see things in real time and say what we thought we were seeing.

And as we saw live pictures coming in we could hear the pilots of the ROV onboard the ship, we could hear everybody on the ship we wanted to and we could communicate with everyone who was listening in. We had also conference calls going on at the same time. So we had voice, we had iChat, we had Skype. So that to me was a real first. And so we were able to see things in real time and say what we thought we were seeing.

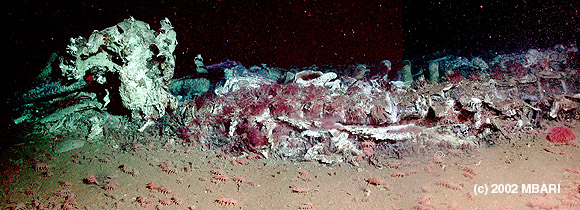

So what we did was we documented what's on the deep seafloor north of Indonesia and we had some remarkable results.

In short, we found very high diversity. We found diversity that rivals that of the shallow water coral triangle area. The region we looked at was between 300m and 5000 m deep. So we covered a lot of different kinds of habitats - mid ocean rift habitats, a lot of deep sediment habitats.

We actually found wood and coconuts that were being uses as habitats by certain species. There's lots of wood that falls into the water in this part of the world and it actually hosts a different kind of chemosynthetic community, those communities that live on decaying material.

We think we found more that 40 new coral species and even more other invertebrate species. So it's a really dramatic find.

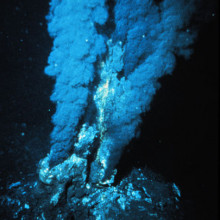

Helen - You mention the fact that there's a lot of wood down there, which is fascinating. But there are other chemosynthetic organisms down there that are living off these interesting chemicals down there on these sea mounts. What's going on with those?

Tim - The sea mount where we found these hydrothermal vents is called Kawio  Barat and we found clams in the outlying sediment that have bacteria in their gills that allow them to take in nutrients and give it to the clam as the host. So it's a symbiotic relationship that allows them to live there.

Barat and we found clams in the outlying sediment that have bacteria in their gills that allow them to take in nutrients and give it to the clam as the host. So it's a symbiotic relationship that allows them to live there.

So we saw lots of clams as we proceeded away from the actual vents themselves. At the vents where the waters coming out we saw a lot of shrimp and a lot of barnacles. These are stalked barnacles that may be 8-10 inches long. They're so numerous. Sometimes we liken it to going through a car wash. They're on ever side of these large chimneys, we call them, like large spires. And they love being there, they're very tough. They love being up into the current where they get nutrients that come in and they're only around these vent systems.

And so we're still trying to identify which species it is - it may be a new species to us. As well as the shrimp that live there. They live in very large numbers and they walk right along the top of the chimneys and through the water coming out.

And there may be three species of those, we're not sure yet.

Helen - Very exciting. So I guess there's an awful lot we still need to discover about these habitats? There must be most questions than answers at the moment?

Tim - Oh yeah. Every time we had a dive, whether it was shallow water or deep, we found something new.

Tim - Oh yeah. Every time we had a dive, whether it was shallow water or deep, we found something new.

The amount of diversity we saw at 300m was really remarkable. And the coloration of the animals - they blended into their surroundings. Even at 300m where it's black, pitch black to us, they seem to be using camouflague for some reason. They still have it, for some reason they haven't lost their ability to have camouflage.

When you go deeper you loose that colour. We were seeing wood at 3000-4000m, all the animals were white. They were nothing like anything we'd seen anywhere else in the sediment or the vents of anywhere else.

The thing is with this vehicle we had, we couldn't sample. So we couldn't bring them back to the lab and dissect and play with their morphology. We could just take pictures and video.

That said the high definition video was very of high resolution, so we were able to get in really close. In some cases count the little hairs on the back of the shrimp that helps us identify who they are. And that's what we're in the process of doing now, is identifying who all these species are. Again, remarkable diversity so it will take some time.

Helen - You mention that this is the beginning, you expedition to Indonesia this year was the beginning of a long term project. What's next for that project?

Tim - This was year one of five actually. We have planned another cruise to the east of where we were last year, it's called Halmahera. We think is has chemosynthetic communities there. It's not venting there, it's seeping, it's coming up through sediments. So it's cold nutrients that are coming up.

We normally in those areas see clams and shrimp and tube worms. We're looking forward to it. It'll be a another month-month and a half long cruise to there. And I know we're going to find some really incredible stuff.

Find out more

Tim Shank's Lab at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

NOAA ship Okeanos Explorer

31:00 - Critter of the month - Osedax: The zombie worm

Critter of the month - Osedax: The zombie worm

with Greg Rouse, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Deep sea biologist Greg Rouse picks the bone eating worm as our Critter of the Month.

Greg - I'm Greg Rouse. I'm a professor here at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. And if I had to be a critter I would choose Osedax, which are bone eating worms.

These amazing animals live in the deep sea mainly. And what they're doing is as little baby larvae they are swimming around in the plankton.

These amazing animals live in the deep sea mainly. And what they're doing is as little baby larvae they are swimming around in the plankton.

They're waiting for occasional bones of a dead whale falling to the bottom. They then land on these bones and of course most of them never have a chance to land on a bone because they die.

But those that do, land on the bones and they grow up by co-opting bacteria to live in their tissues and working together with the bacteria they dissolve the bone and eat the fats and collagen in the bone.

What's amazing about them is that the ones that initially settle are all females. So it's females that dissolve and eat the bone.

And then once they've covered the bone, any new babies coming in are taken by the females and made into little dwarf males. So the females actually accumulate harems of dwarf males.

So far we've found 17 species of these amazing animals. And they were only discovered in 2002. And we think there are probably many more species of these all over the oceans of the world, waiting for bones to fall to the bottom.

So far we've found 17 species of these amazing animals. And they were only discovered in 2002. And we think there are probably many more species of these all over the oceans of the world, waiting for bones to fall to the bottom.

The other thing we've been studying is when they might have evolved, because whales have only been around for about 50 million years. And some of the recent work we've done has shown that in fact they'll eat fish bones and other mammals bones.

We're starting to think that they might have been around in the Cretaceous, back more than 65 millions years ago when they could have been eating vast bone resource such as plesiosaurs and mosasaurs. So they might actually be a very ancient group of worms.

Their closest relatives are actually hydrothermal vent worms that are gigantic animals called

Riftia. And all this groups actually, we've now discovered are not anything more than derived relatives of things that we're familiar with such as earth worms and other things called annelids.

So the amazing worm Osedax is really just a very very bizarre relative of earth worms.

Find out more

Greg Rouse's lab at Scripps

Vrijenhoek, Johnson and Rouse (2009). A remarkable diversity of bone-eating worms, (

Open access paper)

- Previous Flowing through Bioreactors

- Next Is the ice in the freezer edible?

Comments

Add a comment