Cake, Cows, Climate Change: Best Of 2020

In this week’s special episode, we’re reflecting on some of the science we’ve reported on this year. Of course, the Covid crisis means that throughout 2020 we’ve brought you many interviews and updates on the Coronavirus, the lockdowns, and the vaccines. But, as it’s the holidays, we’ve decided to focus on the other science we’ve delved into over the past 12 months. We hope you enjoy it, and here’s to a brighter 2021...

In this episode

Cooking up a haggis!

Tristan Welch, Parker's Tavern

We’re about to bring out the main course: haggis. It’s Scotland’s national dish, but the squeamish among us probably prefer to eat haggis without thinking about how it’s made. But last week’s podcast was all about reducing food waste, and it's important to recognise how good a job haggis does here. Phil Sansom went to meet chef Tristan Welch to learn how to cook the delicacy - and for the uninitiated, there’s talk of blood and guts coming up…

Tristan - So we're going to make haggis. We've got all the ingredients laid out here. The key ingredient, these fabulous things: lambs lights or pluck. What do you think?

Phil - It's horrible! Oh, I hate it, I hate it.

Tristan - A pluck or a light, you big Jessie, is basically everything from the tongue of the lamb right the way down. So we've got our lungs, the liver, the kidney, the heart... some people use the windpipe, some people don't. I think it makes a bit of a dirty haggis rather than a clean haggis.

Phil - Why does a haggis use all of this?

Tristan - For me it's about using the whole animal. Everything's taken, cooked, and made completely delicious and stuffed inside a sheep's stomach. We're going to trim it down first and the bloodier bits, we will discard. I'll do it like so, I'll show you.

Phil - As Tristan went to work on the assorted lamb bits, I tried not to lose the lunch I'd had earlier.

Phil - I need to get a stronger stomach.

Tristan - Well we've got a sheep stomach. Is that strong enough for you?

Phil - I'd really rather it wasn't here.

Tristan - Here we are. This is our lungs, our liver, our hearts, our kidneys, they've all been diced up. We've taking some of the thicker tubes out, let's say. I've put in some bay leaves, some salt, and we're just going to cover it with water and simmer it for about an hour.

Phil - Are they very different to cook with than a normal slab of meat?

Tristan - Gosh, completely different. You have to be very, very delicate with it. But one of the... one of the funny things, the strange things about cooking a lung is it floats on water! So it's just difficult to cook.

Phil - What, do you have to push them down?

Tristan - Yeah, yeah. So we'll put some paper on top and then another pan, and that will just keep them submerged underwater.

Phil - As the lamb's pluck simmered, it went from bright red-coloured to a deeply unappealing grey.

Tristan - I've taken them out of the cooking liquid and I've chilled them down, and I've mixed it with some onions, which I've sweated down in suet. I've got some more suet fat, beef suet fat, and I'm going to put it all through the mincer. It looks pretty gruesome at this point, I have to admit, there's nothing particularly glamorous about making a haggis; but wait until the end product. Back in the 1800s didn't they believe that haggis was an animal that you'd catch? And it's got one leg shorter than the other one so it can run round hills.

Phil - That sounds like something you'd tell to a fool Englishman.

Tristan - You now, I used to live in Scotland and I was called a fool Englishman for many, many years.

Phil - Really?

Tristan - Yeah, yeah! Let's mince away then...

Phil - I can only apologise here, because the sound of haggis mix going through a mincer might be the most unpleasant sound I've ever recorded.

Tristan - And there we are. So you add a generous amount of oats to it, it's almost 50:50. A good pinch of salt. So now we add our spices, which is nutmeg, coriander, allspice, black pepper - that's the really important one. But people always have their own spice mix and they keep it a very closely guarded secret. And to this lovely mix we're just going to add a little bit of our cooking stock, which I've had reducing down there on the stove.

Phil - With the mix ready, Tristan got out the container for the haggis: a cleaned, pale white, cord-textured lamb's stomach.

Tristan - We're stuffing away here. I've taken a nice tennis ball size of the haggis. I've popped it into our lamb stomach, and now I'm gently tying around so it forms a little parcel. Trim the string... and there we are. That's our haggis and it's ready to be poached for about an hour.

Phil - Are you looking forward to eating it?

Tristan - Yeah, it's going to be delicious!

05:52 - Love is in the air... so are bees

Love is in the air... so are bees

Steven Poyser, Cambridgeshire Beekeepers Association

With the love hearts decorating shop windows, and meals for two advertised in restaurants - you’ve guessed it, Valentine’s Day is around the corner! Katie has this report...

Katie - If you think your love life has it tough, spare a thought for the humble honeybee. Romance is hardly the buzzword when it comes to bringing new bees into the world. So, perhaps, it's rather surprising that allegedly Valentine's day and bees share a few things in common.

Stephen - One of the patron saints of beekeeping is Valentine. The word honeymoon is believed to come back from the ancient German, specifically used for the feeding of honey to the groom at the time of their wedding for one month or one moon cycle in order to build their strength up to produce a strong and healthy family.

Katie - Bet you didn't know that! That was hobbyist and expert beekeeper, Stephen Poyser from the Cambridgeshire Beekeeper's Association. He told me all about how honey bees find love.

Stephen - This time of year, being February, there are no males at all in the UK. The males are only created when the colony requires some males, so they won't produce any until March or April. They are produced from an unfertilized egg. So there is no father to a male. Queen lays the eggs 24 days later in the hive. They hatch, they then wait a little while to build up some strength. They're lounging about. They don't do anything in the hive at all. They don't process honey. They don't collect nectar. They don't collect pollen, they don't feed any bees, they don't make any wax. They do absolutely nothing in the hive. Just eat and lounge about just waiting for their time to become sexually mature in order that they can then become what their purpose is.

Katie - In the meantime, what are the females doing?

Stephen - All the workers are females and there is only one queen. A bigger bee being the queen is fed better food in a larger cell in a vertical position to become a queen, and if it's only in a worker cell, it will become a worker. If for the first three days of its life, the queen is killed, the colony can convert any one of those young larvae and they can produce an emergency queen.

Katie - Hmm. Doesn't sound like female honey bees get the best deal. Chances are you'll be a worker putting in all the effort, whilst the males just slob around. The queen once sexually mature, exudes pheromones and then flies into a crowd of sexually mature male drones and they chase her. The fastest flyers get the privilege of mating about four or five per flight, maybe for three or four days. Mind you, being a male honeybee isn't exactly a picnic.

Stephen - Unfortunately for the males, the ones that are successful and catch the queen, when they mate with her, their genitalia explode and they drop to the ground dead. Uh, it's a one off experience for the male! And when the successful males have mated, the ones that are unsuccessful basically then go back to their own hives or to other hives because they are allowed in and they recuperate. And then, off they go in again in the next few days.

Katie - Ouch. And what about the queen and all this?

Stephen - When she's in full production, she could be laying 2000 eggs a day. In the spring, each one will be fertilised. So those will become workers, which is why within a beehive you can have some bees that are slightly gingery, some that are black and some that are a bit more stripy because although they've got the same mother, they may have a different father. The queen will live for up to three years. All of those eggs that are fertilized are with semen that she has collected during her mating flights at the start of her life. That is a phenomenally long time and it is a huge number of sperm that she actually holds, which is why the period of mating is so critical for the bee because if you get bad weather, then they can't fly, they can't get mated, and colonies are in trouble. And that is a major issue with bees at the moment. The, uh, reproductive ability of the queens seems to be declining. They are not living quite as long and not producing as many bees because if they are unproductive, the workers will actually replace her with a new queen and get rid of the old one.

Katie - Charming. So perhaps honey bees won't be cast as Hollywood romantic leads anytime soon, but at a time when pollinators are feeling the pinch, what can we do to spread the bee love this Valentine's day?

Stephen - The best thing that anybody can do if they don't want to keep bees is to provide them with food, and most bees can find food during the summer. Spring is the critical time. So anybody who has a small area of land, if they can plant something that's going to produce pollen in particular for January, February or March, that is the critical thing for bees. They can store nectar in the form of honey through the winter to keep them going in the spring, but they can't store pollen as well. It's the protein they need in order to build up their young larvae.

10:17 - Katherine Johnson - NASA mathematical legend

Katherine Johnson - NASA mathematical legend

We were saddened to hear of the recent death of NASA’s mathematical legend, Katherine Johnson. It was her calculations that got men to the moon, and safely home again. Indeed, some astronauts refused to fly unless she’d personally looked at the figures. Adam Murphy has been reflecting on her contribution to the space race…

Adam - Katherine Johnson, legendary NASA mathematician, passed away on February 24th at the age of 101. Johnson was renowned for her mathematical abilities. She began work at NASA’s predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, where she was a human computer, reading the black box data from aeroplanes. She spent her time there segregated by both her race, and her gender. Eventually, it was impossible to ignore her mathematical skill and she began assisting with NASA spaceflights, although she still faced pervasive discrimination. She calculated the trajectories rockets needed to be launched at, and even the times at which it was possible to launch them at all. Overcoming the barriers faced by black women in the sciences, Johnson’s work is part of so many iconic moments in NASA’s history. Johnson calculated the trajectory for the rocket, and the launch window for Alan Sheppard’s 1961 mission that made him the first American in space. When electronic computers began to be used at NASA, astronaut John Glenn refused to accept the figures until they had been checked by Johnson, stating “If she says the numbers are good, I’m ready to go”. Johnson was involved in the first mission that put men on the moon, helping to calculate their launch trajectory. And when Apollo 13 announced that “Houston, we have a problem”, Johnson’s work on backup procedures helped to get them home safely. Johnson’s contributions to the history of space travel went relatively unrecognised for decades, but in 2015 she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama, the highest civilian honour the United States gives. And she and her colleagues were also the focus of the 2016 film Hidden Figures. A fitting honour for someone who’s work has impacted so much of modern science.

12:45 - Spacewalking: the view from the Space Station

Spacewalking: the view from the Space Station

Steve Swanson, NASA Astronaut

Steve Swanson is a former NASA astronaut who during his career helped build the International Space Station, and is a former ISS commander. Phil Sansom asked him about his tips for dealing with isolation, as well as what the view is like from so high up...

Steve - My first spacewalk, I went out the hatch and I worked my way out to my work site, which happens to be on the very end of the station, the last hand rail on that side of the station. I set myself up getting ready to work, started working, all this; and then the sun comes out and I get to see the earth way down below me and the space station off to the side. I gripped my hand rail so tight I didn't move for a minute. Because it was like this idea that you're way above Earth with nothing below you, and you should be falling down, and this is not a safe place to be. It's not on a conscious level, like "I can control this, I can figure it out". There was some sort of innate kind of fear thing and you don't really have much control over it for a minute until you calm yourself back down.

Phil - That view that you get... how does the view you get of the night sky from the ground compare to what you get when you're up there in space?

Steve - The biggest difference is there is not an atmosphere to look through. So there's no twinkling of the stars, they're all just pinpoints of light. It was not so easy to stargaze on the space station. We don't really have a window that goes up. If you wanted to look at a star, which we'd get to a couple of times because we'd move the altitude of the station a little bit, we had to make this area really, really dark. And it's like trying to see the stars from inside your house: if there's any lights on at all, it's gonna ruin it, you can't really see anything. So we would... I made a blanket with Velcro on the edges that I could put around this whole area and really make it dark, and then we could watch the stars.

Phil - I don't know about you - are you in lockdown like so many of us across the world?

Steve - Yes. We're at a stay at home policy here in Idaho.

Phil - How does that compare to being up there in space with maybe just a couple of other people? Is there a similar isolation or is it very different?

Steve - Yeah, I guess similar in a way, it's quite a bit easier right now, at least where I am. Because I can go out and go for walks or runs or go to the grocery store. I can still do all those things. I just have to be careful about what I do when I do that. On the space station, I mean, you just can't go outside, right? And so you're stuck inside for almost six months.

Phil - Have you got any tips then for how to keep healthy and emotionally OK? And generally well?

Steve - Yeah, so I mean it's... everybody's gonna be different, so I'll say what works for me and maybe people can take this and adapt it for what works for them. First thing was: stay busy. And that wasn't really a choice on the space station, it was a very busy schedule, it was like a 12 hour work day. So I didn't really think about, "oh, I'm isolated, I can't go back home and can't do these things". I was enjoying my time up there and I was busy. Next thing is: stay in communication with your friends and family. And the last thing I like to say is: definitely have some fun too, because now if you're stuck in your house, you're not going to be doing the same things you would normally do. And we did that on the space station, we came up with new games to play in this floating environment, and it helped relieve all our stress and tension.

Phil - Like what sort of games?

Steve - Oh man. Well we had Nerf dart guns, so we would come up with a game of... we could do duels. We had a full-on Nerf dart gun war the first time we brought out the Nerf dart guns, and there was only nine bullets out of all this and it took us an hour and a half to find them. So we decided not to do that again, so we came up with, everybody gets one bullet, we'll just do duels and stuff like that. Competitions to see who could do the most flips... basically our fun day was Sunday. We played all sorts of games.

18:02 - A crisis of reproducibility

A crisis of reproducibility

Brian Uzzi, Northwestern University

Today, high-ranking scientists are expected to volunteer their time to review work in their field before a journal will publish it. This reviewing is the foundation of trust that science today is built on. But how sturdy is that foundation? Are there parts that should be done differently? Brian Uzzi is here from Northwestern University, he researches the sociology of science, and he discussed the subject with Chris Smith...

Brian - The process of peer review works very well in some ways, but there's definitely room for improvement. So peer review basically tries to do two things. One, it wants to make sure that the findings are presented and the study was done correctly. Were the right statistics used? Were the right inferences drawn? Etc. And then the other thing that peer review tries to do is to make sure that the result is reproducible, that it can be replicated; do that's something that is published today, will work for the public tomorrow, for a week from now, for a month from now, even over an entire lifetime.

Chris - And how reproducible is the science then? If the whole process is working really well, we should have really, really reproducible papers. Are they?

Brian - Well, the issue here is that we're beginning to see that scientific papers reproduce at a rate lower than expected. In psychology, economics, and some parts of medicine and biology, we're learning that about 60% of the papers do not replicate.

Chris - Goodness me! So 60% of the science, if I take a paper off the shelf and I copy what the scientist who wrote the paper did, and I try to repeat their work, I get a different answer. Is that what you're saying?

Brian - That's precisely what I'm saying. So you use exactly the same procedures, you do exactly the same experiment, but maybe you only change the subjects in the experiment - and you find out that the first result was a fluke, not a fact.

Chris - But that sounds like a disaster!

Brian - Well, this is one of the reasons why people are beginning to look at this problem in much more detail; trying to find ways in which to improve the process of science so that more papers will replicate, and trying to find ways to predict whether a paper will replicate or not before it gets into the public domain.

Chris - But do we know why this is happening Brian? Has anyone unpicked the process that's leading to a paper just not working? Is it deceit on the part of scientists? Are they just publishing fraudulent science, or is something else going on?

Brian - Good question. The first thing that people looked at was, is this being driven by deceit? And there's very little evidence that it is. It appears that these are honest mistakes that are occurring in the research process itself. Now what you have to remember is: some papers will not replicate, you can't expect a hundred percent replication. Science is an innovative field; you're going to have experiments that end up on the cutting room floor, so to speak. But 60% is too high. And currently people are trying to bring that level down by understanding better the research process itself, and training people to learn how to make sure that their research replicates before they submit it for peer review.

Chris - Who are the worst culprits?

Brian - Currently, we can't give an answer to that because we haven't really begun to look at replication in all branches of science. Science is an amazingly diverse area of study, everything from the very hard sciences where you might look at, like, power station reliability; all the way over to mental health. What we do know is that the areas that we have looked at so far do vary in their levels of replication. So psychology and economics, medicine, some areas of biology - up to 60% of the papers appear to be failing. In other areas like engineering it appears to be lower.

Chris - How are you actually studying this? And I have to put it to you, is your research reproducible?

Brian - I could answer one of those questions! No, just joking. One way to do this is to improve procedures that scientists would use to make sure that their papers will replicate. Another way to do it is to develop procedures that allow someone who is reviewing someone else's paper to know whether the paper will replicate or not. My approach to that has been to develop an artificial intelligence system that reads papers, finds cues in the papers that human beings otherwise miss when they're reviewing the paper, but the AI system can tell us correlate with an accurate prediction about whether the paper will or will not replicate.

Chris - And does it work?

Brian - It works approximately 80% of the time. But the important thing is that for the papers that it feels most sure about - because the artificial intelligence system gives you a level of confidence in its prediction - for the top 10% of its most confident papers, it's right a hundred percent of the time. So that gives you real security in knowing that if you were to go to these papers and use them for whatever - investment purposes, what to build on in future research - you can be fairly convincingly secure that you're building on a fact, not a fluke in the paper.

22:49 - Cows licking cows: social dynamics of a happy herd

Cows licking cows: social dynamics of a happy herd

Gustavo Monti, Universidad Austral de Chile

Gefore social distancing, when we saw our friends we might have shaken their hand, slapped them on the back, or even given them a hug. Cows, though, choose a more intimate route and lick each other on the face and neck to say hello. Now, new research from the Universidad Austral de Chile has used this licking behaviour to assess the hierarchical relationships between cows in a herd - as lead researcher Gustavo Monti told Eva Higginbotham...

Eva - To be completely honest, in these trying times, I can't really think of anything more relaxing than sitting in a field and watching a group of cows lick each other. And that's exactly what members of the research team did every day, several hours a day, for a month: noting down who licked who, who got the most licks, who got the least licks, and how this changed over time. But the question remains: why?

Gustavo - One of the motivations of this study has to do with one consequence, which is arising from the way that we are managing cows, let's say in the Western type of production especially. Our systems are very intensive nowadays. And as a part of the management, animals are grouped and regrouped very often for different purposes. This is a problem because to establish this hierarchy and this relationship for a group of cows takes some time. The problem is once they reach this equilibrium, or status of recognition, then because of the management, some of the cows - or even the leader - is removed from the group and then new cows or new animals come to this group. Therefore they have to reestablish all the process all over again. And this has happened several times within a year within a group, and within the life of the cows.

Eva - Previous studies have shown that the constant reshuffling of animals can make them stressed out, and farmers have known for a long time that stress can have a big effect on milk production. The researchers wanted to understand the effects of this reshuffling on the social dynamics of the herd, and realised that they could use licking events as a window into these social dynamics. So they observed the cows without interfering.

Gustavo - We are some sort of Big Brother, yeah?

Eva - And plugged the data into a computer to perform a modern technique called social network analysis, where each cow is represented by a node and they could scrutinise the complex web of relationships over time. Kind of like Facebook for cows.

Gustavo - It's the same technique that is used nowadays with big data. So when Facebook or whatever company wants to evaluate who are your relationships, with whom you are working, or with who are you in contact; it's the same sort of techniques that were used for our situation. One of the important findings of this study was that unexpectedly, dominant cows licked more than the younger cows in the group, and seems that this could explain that the leader in some way, is offering this as a sort of action to reward the low level animals to keep the cohesion. I think one important finding is that in social grooming in both ways, they can establish individual bonds between members of the group. And this also enhances the overall social cohesion of the herd.

Eva - They also found that cows that were new additions to a herd were licking more often, and hypothesised that maybe they were doing favours and trying to be friendly to get down with the new group. Interestingly, though, the cows that did the most licking received the least licks in return. This might be because licking another cow is something of an investment. And if you go around licking everybody, it might suggest that you're not going to invest in specific relationships, and so the other cow might not bother investing in you either. Overall, Gustavo and the rest of the team suggest that licking can be used as a positive marker for wellness within a herd. If there's lots of licking, things are stable and everyone is content with their friends. If there isn't, things are going wrong in the complex social and emotional relationships of the herd; and Gustavo argues that farmers should be mindful of this important aspect of cow's welfare when reshuffling the group.

30:01 - Jenifer Glynn: remembering Rosalind

Jenifer Glynn: remembering Rosalind

Jenifer Glynn

Regrettably Rosalind’s scientific career was sadly cut short when she died from cancer aged only 37. Greatly missed by her loved ones, she came from a big family with 4 siblings. Speaking with Eva Higginbotham her sister, Jenifer, has many fond memories...

Jenifer - My name is Jenifer Glynn, I'm the younger sister of Rosalind Franklin. I think it was always clear from the start that she was going to be a scientist. She loved developing photographs at home. My grandparents had a dark room she could use, and my mother was keen on photography, developing photographs. She enjoyed actually using the chemicals and doing it was a great pleasure to Rosalind as a child.

Eva - Rosalind's enthusiasm for science took her all the way to Newnham college at the University of Cambridge. One of only two colleges at Cambridge at the time that was open to women.

Jenifer - Rosalind went to Newnham in 1938. Everyone was delighted. Even my grandfather, who was perhaps the most conservative member of the family, gave her a present of five pounds, which was a lot of money in those days. I went to see her in her first year, went with my parents. And I, sorry to say that I was only eight, and all I can remember is the baby ducks on the river. But I did stay with her for a weekend when she was a research student. And she was a marvellous hostess thinking of everything that a 12 year old might enjoy. And it was a very memorable weekend. We saw all the standard Cambridge sites and went on the river. Being imaginative she also took me to see the Newnham baker stirring a great vat of dough, which I also remember with tremendous pleasure. She worked very, very hard at Newnham, but being outside was always important to her: hockey and tennis and cycle rides and skating she was very keen on. But most of her time really was spent on very hard work. She was very perfectionist in her nature, was always determined to do extremely well. It may be surprising to find how very nervous she was about exams, very unsure of herself in that way, right from when she thought she wouldn't get a school scholarship right through to university exams, and even her PhD, she thought would fail. Of course she always did extremely well, but it was a worry. Never anything came easily to her. She always worked very hard for it.

Eva - The university had come a long way in how it treated students who were women, but there were still remnants of the past to contend with.

Jenifer - There were occasional lecturers that would still address their audiences as gentlemen, quite regardless of who was there

Eva - After completing her degree in 1941, Rosalind was awarded a research fellowship at Newnham, and she worked for time at a physical chemistry laboratory at the university. But, the second world war was in full swing and she had to do some war work, which she was very keen to do. She worked for a firm called the British Coal Research Association, where she investigated the structure of holes in coal, which helped in the manufacture of gas masks. The work she did there counted for her PhD.

Jenifer - She was very fortunate in getting a post in France. She loved France, and she was lucky enough to find a post in a French lab, which was investigating the structures of coal and was doing it with the technique of x-ray crystallography, which she was able to learn there. It gave us sort of continuity to her researches because it was always connected with the structure first of coals, then later of DNA, and then of viruses. And although she was not a biologist by training, but a chemist, it was the same techniques that she was then able to apply to biology.

Eva - After four very happy years in France, Rosalind took up a position at King's College London, where she did her famous work on DNA. However, being a woman in science didn't come without its challenges.

Jenifer - It was certainly male dominated. You have to work even harder and be even more sure of what you were doing. That possibly may have inhibited her from guessing in the way that say Crick and Watson did. You had to be terribly sure before you published anything, she did find the male atmosphere that King's uncongenial to say the least.

Eva - I asked Jenifer if she thought Rosalind would be surprised at the attention that her life story and family story have received over the years.

Jenifer - Yes. Simple answer. I think she'd have been totally amazed actually. She would have been very amazed at the idea that she became a sort of feminist icon. It was not, I think, anything in her mind at all. She was just a scientist who wanted to do it all she could in that way, although nothing would please her more than the fact that it perhaps encourages girls into science.

36:16 - Let's get this BBQ started!

Let's get this BBQ started!

Tristan Welch, Parker's Tavern; Eleanor Drinkwater; Barry Smith, SAS; Jane Parker, Reading University

It’s August, the sun is shining - at least, for the minute - and we’re in the holiday spirit! So what better way to celebrate than with a BBQ! Cooking and eating outside can feel and taste like a real treat. First up, Chris went outside to his sunny garden and got the BBQ lit...

Chris - Guess what, in traditional British fashion - it's raining! It has literally gone from sunshine to rain. You would not believe it. I am of course, here with Tristan Welch. And he's been actually knocking up this cake because we are going to cook a cake on a barbecue. If you didn't believe that it was possible, keep tuned in to see history being made. It can be done. So just remind us, what have you put into these cakes Tristan? And how are we actually doing this?

Tristan - Right. Well, first of all, I've got to say, this is not the first time I've ever cooked a pineapple upside down cake on a barbecue, but certainly is the first time I've cooked in the rain! So I've taken the butter and now what you can hear is the sugar and butter in there together. That's being creamed together, so it's a basic sort of sponge mix. To that I add our eggs. Give that a jolly good mix. Then our flour and we're using self raising flour. Now I've taken tinned like individual small little tins. I think they're 250 grams, 240 grams of sliced pineapple. I've taken the top off, poured out the juice, drank it actually, put a one slice of pineapple back on the base with some golden syrup and a cherry in the middle of the pineapple slice. And I'm just about to pop this cake mix on top of it.

Chris - Just the quick rundown of the ingredients in terms of what sorts of proportions? How much of each?

Tristan - 150 grams of unsalted butter, 150 grams of caster sugar, so there's equal quantities. To that I added two eggs and now I've just added 150 grams of self raising flour. We give that a jolly good mix, and that will be quite a tight mixture. So then we add a couple of tablespoons of milk and that loosens it up. In the bottom of the tin I put in about a tablespoon of golden syrup, and one slice of pineapple with one cherry in the middle.

Chris - And then you're going to spoon in, what, fill that in to the brim with mixture?

Tristan - Yeah, take this mix. And this mix fills about four tins up quite nicely.

Chris - Okay. And that then goes - we've got a barbecue with the lid - that's probably important is it? Cause we're basically using the barbecue as an oven.

Tristan - It's vital. So the actual thought process behind it is the heat from below is quite aggressive. So that's going to boil the syrup and the syrup will protect it and prevent it from burning. The lid creates the oven like effect. So it will bake as an oven, but be able to take the aggressive heat from below.

Chris - Temperature gauge says about 200. Is that, 200C, bit hot?

Tristan - That's about right. That's about right. With barbecuing it's about using your senses and feelings and you know, after five minutes you can see it starting to bubble up. If it's not burning it's okay. But definitely around about the 200 mark is about perfect.

Chris - How long do you anticipate we're going to need to put this on for?

Tristan - I'd say about 15 to 20 minutes.

Chris - OK, thanks Tristan! Also with me is biologist and champion of the world of creepy crawlies, well known to The Naked Scientists, that's doctor to be (soon), Eleanor Drinkwater. She's just a gnat's whisker from handing in her PhD thesis. Welcome to the show, Eleanor, you've brought along something for the feast. What is it?

Eleanor - Yeah. So I brought along some edible crickets. In a variety of excellent flavours as well! So these guys haven't actually tried them to my knowledge. Is that right?

Chris - You're going to make me and Tristan eat in insects?

Eleanor - Yes. You're going to discover how wonderful insects are. It's probably going to change your life.

Chris - I have to say Katie, that actually I knew Eleanor was on form. Cause I came out to start the show and she's already caught us a wasp and got it under a glass buzzing around on the table. And I said, " are we going to barbecue that?"

Eleanor - No, no, no, no, no, no. You have to watch it and admire it before letting it go very gently. That's what you have to do when you find a wasp.

Katie - You're very brave for catching wasps. I am not a fan. Sadly, no barbecue for me over here in the studio! But to console me down the line is a flavour chemist Jane Parker from Reading University. Jane, what does a flavour chemist get up to?

Jane - Well, we do a lot of sniffing and our job really is tied to identify the key aroma compounds that are in the foods and work out how they're formed and how they interact with other components in the food. And how they're released and eventually how we actually perceive them. So it's the whole story really.

Katie - Sounds delicious. And we'll come back to you very soon. Also with us is sensory scientist Barry Smith. Barry, how does your research relate to food?

Barry - Well, I'm interested in finding out what happens in us once these wonderful flavour compounds have got together in the way that Jane described. So I look at the science of tasting and I'm looking at how our senses work together, touch, taste, smell, maybe sight, maybe sound, to give us that unique experience of the flavours of foods that we like.

38:44 - BBQ-ed pineapple upside down cake

BBQ-ed pineapple upside down cake

Tristan Welch, Parker's Tavern; Eleanor Drinkwater; Jane Parker, Reading University

The proof of the pudding is in the eating, as they say....

Chris - Well, Tristan's got one of the cakes out. It's on a plate in front of us. Do you want to do the honours, Tristan? Are you going to cut us a slice?

Tristan - Yeah, absolutely. Here we are. So I've just decanted the cake out onto a plate. I've pulled the paper away. I'm just going to cut it in half now.

Chris - It just looks amazing. Oh, seeing it, Tristan's just cut it in half, and the pineapple on the top, the cherry turned beautifully gooey in the middle... a nice wasp buzzing round for you, Eleanor...

Eleanor - I was just trying to catch it, actually.

Chris - The rain has stopped, which is amazing. You can work wonders Tristan.

Tristan - You catch it, I'll cook it.

Chris - Right. Are we going to go for it? Let's have a fork each. Eleanor, have a...

Eleanor - Oh my goodness, this looks incredible.

Tristan - I'm just going to use my fingers.

Chris - I'm going to try and get a bit that's got some cherry and some pineapple. Oh, this is amazing. Katie, you don't know what you're missing.

Tristan - You've had your cake before you've had your sausages there.

Chris - Yeah, I haven't had the sausages yet. I'll have one of them in a minute. Jane, you're missing out big time. Sorry that you can't have any of this delicious cake.

Jane - Yeah, I know!

Chris - The pineapple on the top - on the bottom rather, but on the top when Tristan turned them over - is this beautiful texture, and the most amazing array of flavors that doesn't taste like pineapple does when it's just raw in a tin. Why has that happened?

Jane - Well it's a very clever idea making a pineapple upside-down pudding on the barbecue, because that aggressive heat you were talking about earlier really heats and caramelises that syrup that's on the bottom. And then the pineapple: when it's fresh, it has lots of esters and some sulphur compounds that make it a bit tropical, but once you start heating it, it caramelises as well because it's high in sugar. And you get a compound called furaneol, which has got a really candyfloss, toffee-type aroma. And that really gives your pineapple that gorgeous caramel toasty aroma, because it's been in contact with that high heat on the bottom.

40:05 - Not everyone has an average period

Not everyone has an average period

Caroline Overton, Royal Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Not everyone has the average period described in the quick fire science earlier. In this section, we hear a tough personal account of endometriosis, and discuss the science of endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome with gynaecologist Caroline Overton...

Sophia - Before experiencing endometriosis, I didn't know that such pain was possible every month. I would find myself on the floor fluttering in and out of consciousness as an invisible hand seemingly worked to slice my lower abdomen apart with a series of blunt knives. I was so scared. The first doctor I saw told me some people just have painful periods. Fortunately, I didn't listen.

Eva - Endometriosis affects about 10% of people with ovaries worldwide, where cells like those that line the womb, the endometrium, grow where they shouldn't - like on the ovaries or fallopian tubes. These misplaced cells respond to the same cyclical hormonal cues as the endometrial cells in the womb, so with each menstrual cycle, they grow, and then shed. Only because they are outside the womb, they can't leave the body through the vagina and instead can cause irritation and pain. And this in turn can lead to the growth of scar tissue and adhesions between organs.

Sophia - I'm now post-op and things are much better, but there is no cure, only management. And I worry everyday that a resurgence of that immobilising pain, those days of lonely desperation and fear, await me just around the corner.

Katie - That was Sophia there sharing her experience. And you also heard from Eva Higginbotham. Caroline, is it common with endometriosis to experience that level of pain?

Caroline - Well, thank you for sharing Sophia's experiences. I'm very glad that she didn't take the doctor's advice that it was normal. Very much wasn't, and that sort of severe pain where she is in agony is not normal and is classic of endometriosis.

Katie - In Sophia's case, she had surgery, which helped what are the treatment options short and long term with this condition?

Caroline - So the main aim of treatment now would be about picking it up as early as possible so that hopefully you can avoid the long term complications such as adhesions and infertility. So the current guidelines are to actually make the diagnosis based on the symptoms. So somebody like Sophia coming along and saying, I'm doubled up with my period. That should flag up that she might have endometriosis. There are painkillers, there are treatments like the hormonal pill. Basically, you want to make the periods either disappear completely or shorter and much lighter in order to control the endometriosis and the symptoms.

Katie - Are there fertility implications here?

Caroline - There are fertility implications. Endometriosis starts as little pimples in the pelvis, which are slightly sticky as they grow and develop. And those can cause the organs to stick together, which we call adhesions, and the adhesions then can get in the way of the egg escaping from the ovary and/or getting down the fallopian tube, causing infertility in the longer term. What we don't know is why some women get severe adhesions and in other women, it seems to have a much more benign course where it doesn't progress so much.

Katie - What are the theories?

Caroline - There may be a sort of family link there, so an inherited problem - you are more likely to have endometriosis if a family member of yours has got endometriosis and it's more likely to be severe. We think it may be linked with the amount of period, think of that period slightly overwhelming the body's immune system and stirring up the blood cells from inside the pelvis. The other one is that there is an immune modification, that you've got a slightly altered immune response where in some ways those immune cells are not clearing up as well.

Katie - Endometriosis can result in having to manage severely painful periods as we've heard. And managing irregular ones throws a different challenge and one potential reason for this could be a condition called Pcos or PCOS. Time for another quick fire science from Eva.

Eva - Polycystic ovarian syndrome, sometimes called Pcos or PCOS, is a common syndrome whose cause isn't well understood. It's often characterised by its symptoms, which can include the growth of more follicles or egg sacs than is normal on the ovaries. These sacs aren't always able to release the egg inside, which can cause problems with ovulation periods and fertility. People with PCOS can have irregular or no periods at all as a result. And also often have higher than normal testosterone levels, which can lead to symptoms like weight gain, acne, and hair growth on the body in a more typically quote unquote male pattern sometimes with hair growth on the face, chest and back.

Adam - So we've talked about the fertility outlook for people with endometriosis, but what about the fertility outlook for someone diagnosed with this, with PCOS?

Caroline - Somebody diagnosed with PCOS is likely to have irregular periods with long gaps between them. Although some people with PCOS can have regular periods. If you're having long gaps between your periods, you're not ovulating as regularly and there might be a delay in getting pregnant. It's normal to have a period every 25 to 35 days. So if you're getting longer than that, that might be a problem, and you might have Pcos.

Adam - Now the condition is also associated with high insulin levels. So why is that? And what does it mean for someone's health throughout life?

Caroline - Those high insulin levels are part of the changes in the body causing the hormone changes that lead to the effects that we heard about in the snippet there. You get increased production and activity of hormones like testosterone. That high insulin level leads to insulin resistance. So your cells if you like are numbed to the effect of the insulin, and there's a diabetic tendency there.

Adam - How can you manage a condition like this, or what's the best way to go about it?

Caroline - It would be about making a diagnosis. It would be if you are overweight, trying to lose weight, eating a healthy, balanced diet. And if your periods are still very irregular, drugs such as Metformin, which increase insulin sensitivity, and possibly if you're wanting to get pregnant fertility drugs such as clomiphene.

46:46 - Apophis the asteroid edges closer

Apophis the asteroid edges closer

Adam Murphy

On Friday the 13th of November - yes really! - an 11m asteroid skimmed through our outer atmosphere. But astronomers only spotted 2020 VT4 the following day! There was also news out this week that the Sun is pushing another asteroid, called Apophis, closer to us over the next 50 years than we’d like. Adam Murphy has been looking at objects in space like these that come a little too close for comfort...

Adam - Space is big. Really, really big. And it's also, as you might've noticed at night, pretty dark. That means there's a lot of room for things to be hiding out there in the black of space. Some of those things are asteroids and comets, and some of those often get closer to earth than you might think. Objects that get near to earth are called, imaginatively, Near-Earth objects, and they can get close. In 2004 an asteroid about five meters across shot by us, flying below some of our satellites. And if they were to hit, they could cause some real damage. It was an asteroid that killed the dinosaurs after all. And in 2013, a bus-sized object exploded in the skies near Chelyabinsk in Russia. It blew out windows and caused tens of millions of pounds of damages. So it's important to be vigilant.

Many of these objects come from the asteroid belt, which is a belt of asteroids that sits between Mars and Jupiter. Usually, those rocks are content to just sit out there, but sometimes there are big collisions between them and those collisions can send some pretty big pieces of debris our way. Once they've been knocked out of the asteroid belt they continue to orbit the sun, but in long loopy, very oval-shaped orbits. And those orbits can intersect with the Earth's orbit. The gravity of the earth and the sun can even help bring the asteroid back around, like a wasp that refuses to leave you alone on a summer's day. And because space is really dark, we don't always see these things. In 1989 another asteroid call 4581 Asclepius was as close as 700,000 kilometres away, which is about twice the distance between the earth and the moon. But if it had hit, it would have devastated the planet and we didn't detect it until it was nearly on top of us.

One asteroid, in particular, has been on our radar for quite some time and will be ignoring Earth's personal space on several occasions in the next few decades. It's called 99942 Apophis. Supposedly it's called that because the discovers were fans of the Stargate SG-1 TV show, and named it after one of the big baddies. It's certainly how I know the name anyway! It's about the size of the Eiffel tower, and in 2029, will pass under some of our satellites. And it will get close again in 2036, and then again in 2068, although the further into the future you go, the less certain the details are. For a while, this was looking like the most likely contender to hit the planet and cause some damage. At one point, it ranked a 4 on what's called the Torino scale where 1 is "we're fine and there's nothing to worry about", and 10 is "we should prepare for everything to turn into Madmax now."

But there are plans to deal with anything coming our way. The old plan was to just blow it up with a nuclear device but as the general says in one of my favourite movies, Independence Day, that risks turning one dangerous object into many. The new plan is to just give them a push. NASA has a mission planned called the double asteroid redirection test, which will launch in the middle of next year and is going to a pair of asteroids called 65801 Didymos, to test our rock pushing capabilities. Severe asteroid impacts are only predicted to happen once every hundred thousand years, but if we should win the worst galactic lottery and that's going to happen soon well, because I don't know about you, but I wouldn't last too long in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

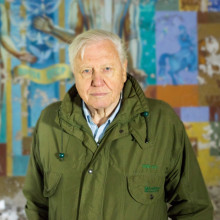

51:00 - Attenborough's new film: A Life On Our Planet

Attenborough's new film: A Life On Our Planet

Colin Butfield, WWF

David Attenborough calls his new film, A Life On Our Planet, "my witness statement and my vision of the future - the story of how we came to make this, our greatest mistake; and how, if we act now, we can yet put it right." Chris Smith was joined by the films executive producer, WWF conservationist Colin Butfield...

Colin - When making the film we realised very, very early on that David has had this extraordinary life. Because of the time he was born and the job he had, we figured that he's probably seen more of the natural world than any other human being who has ever lived or will ever live; because before him there was obviously no air travel, and now so much of the natural world has been lost. The unique life he's had means he's seen something that nobody else has seen, and in the process of doing so, of course, he's witnessed this enormous scale of change on our planet; probably a bigger change to the natural world than any other time in the last 10,000 years. So he has a unique witness, a unique perspective, as a result of that. And that was a very appealing storytelling lens because I think when we talk about these massive global changes, it's quite hard for people to understand, to grasp. It feels huge. Putting it in the context of one human's lifetime makes that somehow easier to understand.

Chris - What will the viewer actually see? How have you done this? Because obviously, Sir David is now in his 10th decade, he can't travel in the way that he once did. So how have you managed to capture the spirit of an Attenborough doco, and do it in a way that brings people the action and has very much his fingerprint on it?

Colin - Well it's interesting! Even though you're quite right, David is 94 - he was 92, 93, when we were making this - he still did travel out to Kenya, to Maasai Mara, somewhere he had been to many times in the past, to show what's changed; and also out to Chernobyl, which obviously is a very different landscape and environment for him. But we start and end the film in Chernobyl and show the change that's happened there, from obviously the human civilisation effectively being evacuated and left destroyed, to nature reclaiming the territory. And we intersperse those location shots with some archive going back to his famous sequences in his career, and also footage from today that shows some of those changes. Some examples being: he's one of the first people to film and present from coral reefs, and then we've shown the modern footage of the same coral reefs bleaching. We've got footage of him in Borneo 40 years ago finding orangutans, and then footage of Borneo today and showing what's changed there. So you get that juxtaposition of what he saw then and what he saw now; but also of course, being David Attenborough, obviously his great expertise is in the natural world, so when describing even changes that are very human-centric he often uses examples of nature to illustrate that. One example would be that when talking about the impact of meat consumption on the natural world, he chose to explain it from the Serengeti and explain in the context of the ratio of predator to prey animals, and how much space prey animals need. There's a hundred prey animals on the Serengeti for every predator. And therefore the space that's needed effectively to produce meat protein, and using that to illustrate the changes that are happening in the human world. So we're able to have the gorgeous wildlife sequences and place lots of them in a very human context.

Chris - There is this phenomenon dubbed the "Attenborough effect": when David Attenborough highlights something, it usually galvanises attention and hopefully also translates into action. The best example being plastics, for example. Are there any things that you have purposefully picked for this one which you're thinking, "we want to provoke people, we want to highlight very important issues, or make people change"? Because it was obvious with the plastic doco that if you show that cause and effect, you immediately show people what they need to do to try to help. Have you done anything similar with this one?

Colin - Yeah. The two things we really, really wanted to get across in this were probably the biggest tipping point issues facing our planet; the biggest places where things will go into free fall, the changes are happening so fast. Those two examples are: the change in the Arctic sea ice and how fast the world's warming, very visually showing the change that's happened during David's filming career, actually not even just his lifetime; going to visit locations where you would expect to be surrounded by ice, and obviously the wildlife that is on the ice and uses the ice for hunting, and the ice not being there. And the second one was tropical forests; in particular, how fast tropical forests have been declining shows that the Amazon in particular, as an example, is approaching a tipping point where the amount of rain that's needed to self-sustain that that rainforest is being lost through lack of rainfall, and also deforestation and fires. And it faces a moment where it might tip into a dry savannah. And then placing those issues back to ourselves, in particular highlighting levels of meat consumption and investment in things like fossil fuels. Although each of those things are a bit more complex than purely a plastic bottle or a plastic carrier bag, which has obviously had a big effect because it's extremely tangible what each one of us can do and what that impact is, I think here we wanted to get a sense of the whole scale of the destabilisation of our planet and what we need to do to stabilise it again. And that's a bigger, more complex thing, but I hope and feel - and certainly the reaction in the first few days seems to suggest - we've got something across.

Chris - Lee, you've made quite a few films, in your case with National Geographic, about your work. It really does work to galvanise attention around an issue, doesn't it? I mean, have you found that interest in paleoanthropology, interest in our human story and therefore people's sort of sense of guardianship of the planet, has improved through what you've done making telly programs that bring the science to people?

Lee - Oh it absolutely does. There's probably no more effective way to reach millions and millions of people with messaging. But just to follow on what was being talked about that Sir David's done here: we're living in a world that's seen the cost of 8 billion human beings. COVID, the destruction of natural habitats, the cost to all other living things. And we need messages like this now, because this is going to be the new norm. It isn't going to be waiting around for viruses when we reach 9 billion and 10 billion and 12 billion consuming humans; we have to make choices, and we have to do it right now.

Chris - Theo?

Theo - Yes, I find this particularly poignant because I was a teenager when David Attenborough's Life on Earth came out, and it was the thing, when I was asked at university interviews "what made you want to study science?" that was my answer. I think he changes a lot of people's lives, and he's really determined now, even in this 10th decade, to keep changing our attitudes to the natural world. And it's really very inspiring.

Chris - And Colin, are you able to sort of capitalise on the program in other ways beyond just sort of making a program and educating people, are there other ways in which you can then take the momentum that's created and then build on that to get more change or to get more activity off the back of it?

Colin - Yes, I think there is. One of the things that's happened already in only a couple of days since we've released it is various big companies, as well as members of the government, getting in touch with us and asking us to host screenings and to share it with employees or with politicians. And I think you find, and hopefully we're going to find with this one, but you certainly find with documentaries, that it can be an interesting moment to provoke a conversation within companies and governments where change can be made. So it ‘lightning rods’ an issue that perhaps many people have been talking about for quite some time, and gives a focal point, a moment where it feels we must respond to this. And that's a sort of sense that we're getting at the moment. It's early days, but it feels like there's a moment where employees are asking their bosses, "what we can do about this, surely we've got to address these issues". And it's not just from one documentary, but it's from a building of this drumbeat over time. And then a documentary like this, particularly if fronted by David, tends to have a flashpoint that draws a lot of attention and forces people to make a statement one way or the other towards it.

Chris - And Lee, is there anything we can learn from what happened to our ancestors that might help to focus minds today? We think that obviously every experience we're having is unique. Is there evidence that actually our ancestors went through times when the planet was under stress, obviously not of their making like the present situation is in our case, but the outcome could nevertheless be the same?

Lee - I think that the thing that humans should take away from the idea of studying the human historic past is that we should lose our arrogance. Extinction is the norm. There have been dozens and dozens of our closest relatives with brains like ours, with adaptations like ours, that have existed through the last millions of years, and they are all gone. And we can go that way too.

Chris - Theo, any passing thoughts from you? It's a pretty poignant and sobering note from Lee to finish on.

Theo - I'm more of an optimist, and I hope that the human ingenuity that has got us into this terrible pickle will help get us out again.

Comments

Add a comment