Fighting The Illegal Wildlife Trade

It's one of the largest criminal industries in the world, worth billions and responsible for thousands of murders, but can we win the fight against the illegal wildlife trade? We speak to the foot soldiers of this battle: a scientist whose new techniques led to the capture of some dangerous criminals, a member of Border Force who intercepts ivory as it enters the country and the man with a gun facing off directly with the poachers, and hear about the animals whose time is running out. Plus, a revelation from the early Universe which might change how we do physics today, why unexpected rain was a course for celebration for some scientists and the crickets who have been found to use tools to amplify their songs.

In this episode

01:02 - Dark Matter revealed in the early Universe

Dark Matter revealed in the early Universe

with Lincoln Greenhill, Harvard University

Scientists have just discovered clues to the behaviour of the enigmatic dark matter, and suggest that it may, contrary to popular belief, be able to interact with normal matter. Two scientific papers in the journal Nature have examined signals from the very early universe, and found that it was colder than expected, suggesting dark matter played a role in cooling it down. Chris heard from Harvard’s Lincoln Greenhill, who has written a commentary summarising the findings...

Lincoln - Before galaxies and stars were around there was just a vast sea of gas left over from the Big Bang. That gas was mainly hydrogen; there was also some helium and there was nothing in it - no stars, no bright objects. The other thing that was around at that time was Dark Matter. Dark Matter is out there because we can see the influence of its gravity on how stars move within galaxies and how galaxies move as they dance about in the cosmos. And we’ve been searching for some time for evidence that would enable us to answer the big question: what is Dark Matter? What are those particles that are causing gravity but don’t seem to interact with radiation? Until now, it has seemed that they only interact with one another.

Chris - How have these researchers managed to get a fresh insight into what Dark Matter might be?

LIncoln - It begins with the first team. They used a very carefully constructed radio antenna which can receive signals at the frequencies that we currently use for television and FM radio. They observed the background, which is left over emission from the Big Bang at radio frequencies. Then they saw a very slight deviation in that signal at frequencies that correspond to what hydrogen atoms would be emitting and absorbing and that very small deviation tells us that the temperature of the hydrogen gas was actually lower than anyone had expected and, in fact, sufficiently low that it can’t be explained. Just normal interactions of matter couldn’t make the hydrogen gas that cold; it has to be losing energy to something else.

Chris - Is it fair to summarise then and say the Big Bang happens, we know there’s a big conversion of energy into material matter and a big chunk of that’s hydrogen? We think we understand what must have happened - the Universe is inflating and growing, a bit like a balloon blowing up and we know how much energy should be there, therefore, we think we know how hot the hydrogen should be but when this group look at how hot the hydrogen is, it’s cooler than the model would predict? So some energy has gone missing and now they’re speculating as to where that heat energy may have gone?

Lincoln - That's correct. At this time, the Universe is relatively simple. We have the hydrogen gas, we have Dark Matter, both left over from the Big Bang, and we have radiation left over from the Big Bang, so there aren’t many places that the energy of the hydrogen could go, apart from leaking into the Dark Matter.

Chris - Why is the hydrogen hotter than the Dark Matter then? If they’re both around at the same time why does the hydrogen lose energy to the Dark Matter?

Lincoln - The great advantage that the hydrogen has is that it can interact with more than just itself. The Dark Matter, so far as we had believed up until this most recent discovery, only interacted with itself. The hydrogen, on the other hand, is able to interact with both itself and with the radiation that surrounds it and, in fact, can interact with the very first stars as they were born approximately 180 million years after the Big Bang. And so the hydrogen can draw upon sources of energy which Dark Matter doesn’t have access to in some sense.

Chris - How do the team think that the hydrogen gives this thermal energy away to the Dark Matter?

Lincoln - We have only the most rudimentary understanding of this at the moment. We think that it’s a process that is like scattering, that it’s billiard balls banging off one another, transferring energy from one to the other.

Chris - What are the implications if they turn out to be right? What are the implications of this discovery?

Lincoln - Potentially, this is revolutionary because Dark Matter makes up most of the matter in the Universe; it outweighs normal matter by at least five times. And we now have a completely new window on a type of physics that no-one had seriously imagined would be the case up until now. Of course, Dark Matter is everywhere: it’s running through our bodies, it’s running through our environment. It does not interact and we don’t see it, but it’s everywhere and so it’s a new universe in some sense.

06:32 - Home blood pressure testing to reduce strokes

Home blood pressure testing to reduce strokes

with Jonathan Mant, University of Cambridge

High blood pressure is a strong predictor of heart disease and strokes, so finding a way to manage effectively it is a top priority for patients and doctors. Now, a team think they may have found a way to improve how we treat high blood pressure without adding a huge cost or time burden: they’re using measurements people take themselves. Chris met up with study author Jonathan Mant to hear how...

Jonathan - About a third of people in the UK already measure their own blood pressure. But then, the problem is that GPs don’t really do anything with those readings, they tend to use the readings that they or their practice nurses take themselves. The question that we wanted to ask was if GPs systematically made use of the readings taken by patients at home, would that improve the blood pressure control?

Chris - Why should there be a difference between the measurements that I get at home versus if I came and sat in a GP’s surgery and got them to do it?

Jonathan - The measurements taken at home are paradoxically more reliable. This is because many people, when they go to the GP’s surgery, are a bit anxious about what their blood pressure might be so often their blood pressure is higher when they take it in the GP’s surgery.

Chris - It’s usually because they can’t find a car parking place.

Jonathan - Ha, yes absolutely. I suppose the other thing I should say about blood pressure measurement at home is that you could take blood pressure lots of times because what we’re aiming to treat when we’re trying to lower blood pressure is what the true underlying blood pressure is. If you just take one or two random readings in a clinic, that’s not a very accurate gauge of what the true underlying blood pressure is. But, at home, you can take it several times a day, several day at week and so, therefore, you do get a better representation of what the underlying blood pressure was.

Chris - How did you do the trial?

Jonathan - We recruited 140 General Practices and within those practices we recruited about 1,200 people who had high blood pressure, and then those 1,200 patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups. The first group was usual care, so the GP was left to manage their blood pressure in the normal way. The second and third groups were both given blood pressure machines to measure their blood pressure at home and they were trained how to use those machines. We asked them to take their blood pressure morning and evening every day for a week, one week per month. One group we asked to send the blood pressure reading back by post to the practice, the other third groups sent the blood pressure reading back by sms messaging.

Chris - So all this data is aggregated, what do you do with all that information?

Jonathan - Two things: the patients have a postcard system that warns them if their blood pressure is too high or too low. If they find their blood pressure is to high they’re encouraged by the postcard to go and see their General Practitioner. The practices were asked to review the readings they received every month and make appointments for people where they had concern. Then we asked the General Practitioners to titrate the blood pressure medications according to those blood pressures.

Chris - So the GPs are able to react to that information coming in and adjust the patient’s treatment but they haven’t, critically, had to take up an appointment space and had to see the patient while all those measurements were being made so this, potentially, sounds a lot more efficient then?

Jonathan - It’s a lot more efficient and it’s partly giving the control to the patient rather than to the GP, and the GP doesn’t have to measure the blood pressure at all.

Chris - When you then follow up and see what happens to blood pressures of these different groups of people, how do they all compare?

Jonathan - At six months, there was significantly lower blood pressure in the group that was self-monitoring and using text messages to get the information back to their GP. At twelve months, there was significantly lower blood pressure in both the self-monitoring groups.

Chris - The differences in blood pressure, were they clinically significant as in I could say well, something statistically significant the blood pressure is a very small amount lower, but actually that’s not really going to make a big different to my heart attack or stroke risk? Is it clinically significant here?

Jonathan - Yes it was. We found that the blood pressure in the self-monitoring groups was lower by 4 mm of mercury. Now that may not sound much but that equates into about a 20% reduction in the risk of stroke and about a 10% reduction in the risk of heart attack.

11:16 - Down to Earth: Folding satellites and maps

Down to Earth: Folding satellites and maps

with Dr Stuart Higgins

In this episode of Down to Earth, Stuart Higgins looks into how satellites have helped us fold our maps...

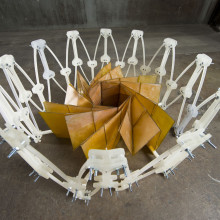

Stuart - Keeping spacecraft powered up during missions is a challenging task. The bigger and heavier something is, the more expensive it is to launch meaning giant batteries are out of the question. Solar panels were a favourite for use in space because they offer a relatively good power to weight ratio, but they also require a large area to operate.

To save space during the launch, solar panels were often folded away inside the spacecraft, slowly unfolding up in orbit. Getting the unfurling right can be one of the more nerve wracking parts of the mission because if the panel gets stuck, the spacecrafts batteries would soon run out of power and its mission over.

In the 1970s and 80s, astrophysicist, Koryo Miura, was working on how to fold solar panels and other structures for space. He mathematically determined an optimal folding method that critically allowed the solar panel to be unfolded with a single pulling movement. This meant that not only did the folding offer the benefit of saving space, it also minimised the number of motors needed to unfold the solar panel.

Miura also took care to minimise how the folds caused tensile stress in the material. If you told a piece of paper in half and the half again, the outside fold has to bend around multiple thicknesses of paper applying greater strain. In his calculations, he tried to minimise the risk of the fold tearing. As well as being useful for deploying solar panels in space, the Miura fold has also been used to make subway maps that can be easily unfolded, presumably by confused tourists struggling to find their way.

And the usefulness of the Miura fold doesn't end there: researchers at Cornell University are excited about how different kinds of Miura fold can be used to create metamaterials. A metamaterial is where a small repeating pattern gives a material new or unusual properties so, in the case of the Miura fold, the repeated parallelogram style folds turn a floppy sheet of paper into something with greater structural strength. The researchers were interested in what would happen if they could apply the same folding patterns but on a much smaller scale to material such as graphene to see how their properties would change.

As for space applications, research into origami related structures is continuing with an even more elaborate folding method being developed that allows solar panels to be deployed in a circle using the rotational force of the spacecraft alone. So that’s how solving the problem of folding solar panels for spacecraft led to easy to unfold maps and has helped inspire research into new ways of working with materials.

14:16 - Unexpected rain and life on Mars

Unexpected rain and life on Mars

with Dirk Schulze-Makuch, Technical University of Berlin

The unpredictable weather this week may well have got you down, but some unexpected weather turned out to be a big help for one group of scientists weighing up the probability of finding life on Mars. Georgia Mills heard why nothing rained on Dirk Schulze-Makuch's parade...

Georgia - Life exists almost everywhere on our planet, but there are a few places so extreme it’s thought nothing can survive. And one of these places is the Atacama Desert in South America which has the dubious honour of being…

Dirk - the driest warm dessert on our planet.

Georgia - That is Dirk Schulze-Makuch and his line of work takes him to the most extreme environments on Earth.

Dirk - It’s very intriguing because there’s not trees, there’s no plants, so if you were there it feels kind of very different. Where you and I come from there’s all the time plants and animals and so life is everywhere around, and there it is not. You just have rocks and mountains and once in while you feel the wind on your skin and that’s it.

Georgia - Dirk and his team had a big trip planned to go and get samples from one of the driest places on Earth. It goes decades without a single drop of rainfall and then, just before they arrived yep, it rained.

Dirk - Yeah, we thought “shoot!”. We prepared months for it for sampling the driest spot on Earth basically and then it rains there before. First we thought it was bad luck, but it turned out to be good luck because of activity of the microbes and two later years these samples went down, so the organisms became dormant again.

Georgia - Previously, the small bits of life discovered in the Atacama were thought to have ridden in on the winds only to end up dying then but when the rains came, this dry desert came to life suggesting that certain things can survive there after all.

Dirk - Mostly bacteria, but we found also viruses, fungi, and archaea, so quite a bit but most of it was bacteria, especially in the most driest area.

Georgia - You’ve gone along to one of the driest places on Earth where we previously didn’t think things could survive there. What you found there suggests they can so what does this mean, what implications does this have?

Dirk - Well, it has direct implications also to Mars because Mars had oceans on its surface early on, about 4 billion years ago, and got drier and drier with time and so Mars still has its moisture events though. You have sometimes fog, you have near surface groundwater, you even have an occasional nightly snowfall or microburst there so there are ways you get moisture on Mars as well. Now the question is: Mars is still a tick harder, so can life still handle that?

Of course, in the Atacama they’re just barely hanging in so can they handle much more? - we don’t know. But looking at the creativity and innovation of evolution, I’m slightly optimistic that this is the case.

Georgia - So you think there’s more hope then that we might actually find something that’s either dormant or living on Mars?

Dirk - Yeah, I’m pretty confident. Once you had a biosphere on a planet and I think Mars had one. It would be very difficult to wipe it all out - it’s like infestations - you have a difficult time to get rid of it, life just wants to hang on.

18:13 - Baffled: Crickets use tools to boost their song

Baffled: Crickets use tools to boost their song

with Natasha Mhatre, University of Toronto at Scarborough

Crickets have been shown to be able to create and use tools for the first time. The insects can amplify their mating calls by creating 'baffles' from modified leaves, getting a volume increase of up to 400%. Chris Smith heard from Natasha Mhatre, who has been investigating how...

Natasha - These creatures are called Tree Crickets. They’re about a centimetre in length - they’re really beautiful. Most of us see crickets from the pet store which look kind of brown and a bit cockroach-like. Tree crickets are really pretty: they have translucent wings, they have long antennae - those small green things - a there’s tree cricket species more or less all over the world. The ones that we’re working on come from India.

All tree crickets do with really amazing thing which is that they sing to attract mates. They put up their wings, which are resonant, rub them together and set them into vibration and produce really beautiful tonal sounds; that’s what you can hear on a summer nights. These sounds are heard by the females who can use them to identify males of their own species from other males, and find the males.These tree crickets also do this amazing other thing which is that they make an aid that helps them be louder than they would be on their own.

Chris - Really; what do they do?

Natasha - They make a things called a baffle. A baffle is, for a tree cricket, very simply a hole cut in a leaf that they sing from. They place their wings directly against this hole and sing from inside it, and this makes them louder.

Chris - Is that a bit like you see people walking around in the old days on Hollywood sets with a megaphone, which was basically a cone with the end chopped off and they shout into it? Is it sort of doing something similar, they’re creating an amplifier from a leaf to make themselves louder?

Natasha - It’s a bit similar. I’ll try and explain the physics as simply as I can. If you can imagine the wings as a board that’s vibrating back and forth. Every time the board moves forward, it produces high pressure in front of it and behind it it produces low pressure, and this is essentially what sound is - its changes in pressure. But what will happen is that the high pressure and the low pressure will meet at the edge of the board, and when they meet with each other they’ll cancel each other out. This is something we call acoustic short-circuiting.

Now the smaller the board is, the more of the sound that’s produced is short-circuited. If you can somehow prevent these two, high pressure and the low pressure from meeting each other, then you can prevent acoustic short-circuiting. And that’s essentially what’s happening when a cricket puts itself in the hole in the leaf. What happens is that the front face of the wing is, effectively, acoustically separated from the back face of the wing and they end up being louder.

Chris - How does the cricket find the leaf and the hole in the first place?

Natasha - Ah, there’s a big secret in that. One of the things that we did was to see whether there are different baffle designs. It turned out, if you model this, you find that some baffles perform a lot better than others. And the baffle that performs the best is made with the largest leaf with a hole that’s exactly the size of wings and placed dead centre in the leaf.

Chris - Right. So next question then: given that that’s the optimal solution what proportion of the crickets actually opt for that?

Natasha - Well, it depends on the situation. But when we did an experiment in which we gave 19 crickets the choice between a small leaf which wouldn’t make such a good baffle and a large leaf which would make a great baffle, 15 crickets made a baffle and every single one of them made a baffle in the large leaf. They made a baffle in the large leaf with the optimally sized hole and they got pretty close to the centre, so all of the crickets seemed to know how to make an optimal baffle.

Chris - Now, given that crickets sing at night, they’re therefore able to work out the size of a leaf, discriminate between leaves that are bigger and smaller. Then having worked out the size of the leaf and made a choice, they’re then working out where the middle is. How on earth are they doing that?

Natasha - Yeah, they are doing that. We have no idea. There may be different ways in which they’re doing this: one is to walk along the edge of the leaf, the other is use these really beautiful long antennae that they have to touch the edges of the leaf to see if the edges are further away on one leaf than another other and using themselves to centre in the middle of the leaf. But, to be honest, the answer is we don’t know how they’re doing it yet.

Chris - How much louder is the baffled cricket compared with a non-baffled cricket? In other words, what sort of an advantage - a sonic advantage do they gain through doing this?

Natasha - A cricket that’s in an optimal baffle will be four times as loud as a cricket that’s on its own.

Chris - This completely changes our view of insects, doesn’t it? Because we mostly think of insects as sort of dumb automatons but here you’ve got very simple organisms, they’re making a sequence of decisions informed by their own measurements in order to achieve an outcome and that’s really quite striking.

Natasha - Absolutely. It has been a long-held view that invertebrates are stereotyped, and vertebrates, mammals, birds, etc. are extremely clever. We’ve been having to change this view. I think one of the first things that really jolted this was when they found that octopuses can make tools. They were making all sorts of tools. Now, if you think about it a little bit an octopus is a mollusk, it’s the same as a snail. So really, we can’t hold onto this idea any more that invertebrates are simpler animals. They’re just different from us and we’re absolutely going to have to look very closely at how insects behave in order to be able to appreciate what’s going on that’s not immediately apparent on the surface.

25:00 - What is the illegal wildlife trade?

What is the illegal wildlife trade?

with Paul De’Ornellas, Zoological Society of London

When we talk about the illegal wildlife trade, what species are hit and why is it a problem? To find out, Georgia Mills went to ZSL London Zoo to meet with scientist Paul De’Ornellas, and come face to face with an animal in danger of extinction from the trade...

Paul - The illegal wildlife trade, it’s a sort of all encompassing term, but it’s looking at some of the issues around those species that are traded, either in whole or in part, and it’s associated with illegality, often associated with international organised crime networks. And it’s rapidly being recognised over the last years as being a really significant issue, not just for wildlife, although that’s obviously why and organisation like ZSL is engaged in it, but also around criminality, governance, lawlessness, undermining local people’s livelihood options and so on. I think that a recent UN assessment estimated that annually illegal wildlife trade accounts for anything up to 10 to 20 billion US Dollars per year, which puts it in the same league as things like narcotics, weapons, people trafficking and so on.

Georgia - We’re standing outside the tiger enclosure, can we go and have a look at the tigers?

Paul - We can indeed. I think the tigers are nestling on their hot rocks which, to be honest, I’m quite envious of today. Yeah, there they are stretched out one arm in the air.

Georgia - Oh yeah. They do not realise it’s snowing out outside do they?

Paul - No. I don’t think we’re going to move them from there.

Georgia - So these overgrown tabby cats, they’re absolutely beautiful. What would someone want an animal like this for in the context of the illegal wildlife trade?

Paul - To be honest, with tigers it’s almost any part of their body associated with traditional Chinese medicine and other tonics and so on, so bones, skin, even blood and other body parts which is a really major issue affecting them today.

Georgia - Oh God. That’s a tragedy really - they’re just so great all in one piece.

Paul - Indeed. It’s hard to put a figure on exact numbers but there’s probably less than 4,000 tigers in the wild at present. That’s gone down from substantially more than that so around about the turn of the 19th, 20th century so it really is imperative that we take action against trade that’s affecting these species or we’ll lose them forever.

Georgia - So these guys have their hot rock they’re resting on. We don’t have the luxury, we’re outside in the cold so shall we go in and warm up somewhere?

Paul - Sounds good.

Georgia - You mentioned earlier this is a massive industry. This isn’t someone just nicking eggs off a beach and eating them. This is like a huge thing so who are the key players involved here in each step of the process?

Paul - It’s a very complex picture. It does actually go all the way from people from rural communities who may be, willingly or not, implicated in the illegal wildlife trade. They may be poaching something and then selling it to middlemen who then pass it on to people further up - a sort of criminal network. It depends really on the product but if you’re looking, for example, something like ivory you’ll see middlemen sourcing them from a number of different locations before they then pass out via either airports or international ports, and then moving around the world. It’s actually incredibly flexible in making use of the criminal networks that ship and trade all sorts of other products as well.

Georgia - Now with us is a little - it looks like an anteater. It’s very furry and very sweet and I’m stroking it now. Not a real animal, it’s a fluffy cuddly one I should point out, but what is this and why am I cuddling this toy?

Paul - I can certainly answer the first part of the question, or try to - this is a pangolin. Species wise, it looks to me like a giant pangolin from Africa.

Georgia - You can identify the cuddly toy?

Paul - I’m being cautious, and no-one else can see it so I’m probably on safe ground. Apart from looking like a little dinosaur and generally being a pretty cool animal, it has the dubious distinction of having been the most heavily trafficked wild mammal in the world at present. For some species we talk about body parts representing two lions or fifty or a hundred elephants, for pangolins they’re traded in tons. Primarily, that’s for consumption in east and Southeast Asia, whether that’s for food or medicinal products.

Georgia - How do you move something of that scale?

Paul - For pangolins, what we’re seeing is, where the scales are often stripped off, put into big bags, and then shipped almost like any other good. And we come back to this idea of illegal wildlife trade or wildlife crime as being another crime.

For the criminals involved, it’s about making money from utilising a product and, unfortunately, these endangered species are the product and whilst it remains relatively low risk, and relatively high benefit then those sorts of criminal gangs are going to get involved. It’s our job and the job of the enforcement agents and others who are trying to protect these species, to try and alter that balance so that it becomes a high risk and lower gain opportunity for criminals and hopefully then they’ll move onto… well hopefully not engage in any criminal activity, but certainly move away from wildlife.

Georgia - Maybe they’ll just stick to theft - plain old theft.

Paul - Narcotics, that sort of thing. Things that don’t bother us.

31:09 - Full metal jacket: preventing poachers

Full metal jacket: preventing poachers

with Andrew Sakala, Wildlife Protection Officer

How do we prevent poachers from reaching the animals at risk? In Zambia; in the South Luangwa national park, they’ve found that one very effective way to protect this game, which is frequently targeted by poachers, is to make it the law that a wildlife protection officer accompanies all of the safari groups and walkers. This means that there’s a very visible - armed - police deterrent wherever the game goes. Chris Smith spoke to Andrew Sakala about his role protecting animals...

Andrew - We are divided into two categories. Right now, some are out in the field conducting anti-poaching patrols to stop poachers from hunting our game. Then some of us work conducting escort duties doing the protection on the guests during the walking safaris.

Chris - Yes, because you’re out with us every day and you’re the bloke with the seriously big gun.

Andrew - Yes. We use AK47s.

Chris - So what’s that loaded with? Can you show me?

Andrew - Yeah, I can. It’s loaded with a mixture of rounds: hard ones and full metal targets.

Chris - Part of your job is to escort people like me around?

Andrew - Yes.

Chris - And you said the other part of your job is doing the anti-poaching side of things. So what does that involve then?

Andrew - It involves anti-poaching patrols. When we are set to go and do anti-poaching patrols in the field we carry everything. We will be out in the field for ten days.

Chris - Presumably the poachers are not nice people?

Andrew - They are not, literally because they don’t know the importance of wild game because all they do is they mean to destroy. When you are confronting a poacher he is pretty sure that if he is apprehended and brought to justice he’s going to be in jail for too long, so trying to rescue from that one he going to do anything but not with the rifle because normally, nowadays, they are using muzzle loading guns which, when he fires once for him to load it it takes some time - a good 20-30 minutes. He knows, with someone handling an AK47 he is vulnerable.

Chris - So really, it’s your physical presence, your very visible presence in the park and that’s a strong deterrent to them? You don’t actually have to fire on them very often?

Andrew - No. When we see the poachers we stalk them. If we start to fight with them they start running away and we try and fire to scare them so that they stop and then we apprehend them and take them before justice.

33:50 - The Sherlock Holmes of the Illegal Wildlife Trade

The Sherlock Holmes of the Illegal Wildlife Trade

with Sam Wasser, University of Washington, University of Cambridge Conservation Research Institute

In the illegal wildlife trade the most dangerous people involved are the criminal cartels, who usually fund the poachers and who then move it across the world. Sam Wasser is a zoologist at the University of Washington and the University of Cambridge Conservation Research Institute and has also been dubbed the “Sherlock Holmes” of the illegal wildlife trade because he’s developed techniques to track down where animals are being poached from. Chris Smith heard about the scale of the problem from Sam...

Sam - It’s quite serious. If you just look at the ivory trade, there’s about 40,000 elephants being killed a year and only about 400,000 left in Africa, so it’s causing quite a bit of damage to the ecosystem. One of the big problems is the amount of profit of the trade and then the other factor is that much of this ivory is being shipped in large shipments, over a half ton. It’s shipped in containers and right now there’s about one billion containers moving around the world each year. You can imagine the problem is that you’ve got a huge profit margin and all you have to do if you are a transnational criminal is get your ivory containerised and get it into transit and you’ve pretty much got it made so it’s made an extremely difficult problem.

Chris - The people, as we heard from Andrew, who are actually responsible for this are not nice people?

Sam - No they’re not. There have been over 3,000 rangers killed by poachers and some people who are also looking at it at a higher level trying to get the big cartels. About 6 months ago a very well known investigator, Wayne Lotter, was murdered in Dar es Salaam and that was really devastating, and there have been others so it’s quite serious.

Chris - The strategy that you’re advocating and have helped to develop, what does it involve?

Sam - Basically, what we’re trying to do is develop ways to get the traffickers before the ivory goes into transit, because once it’s in the transit it’s so difficult to find. So we developed ways to identify the major poaching hotspots in Africa, as well as the major cartels and how many different shipments they’re involved in. The way we do that is, in the mid 1990s, my lab was one of the labs that developed ways to get DNA from elephant dung. So we could get dung across the entire continent of Africa and map the genetics of elephants across Africa.

We then developed ways to get DNA out of ivory and so now, when there’s a large seizure, we are able to get the genotype from those samples and then match it to our DNA reference map and we can tell, with very high accuracy, where the elephants are actually being poached. One of the things that really amazed us was that we have analysed about 50 large seizures over the years and, in the last decade, virtually 100% of these large seizures which are over a half ton, which is 70% of all seizures made, are coming from just two places.

Chris - Right. So you genetically fingerprint the dung so you’ve got a genetic map of Africa, you genetically fingerprint any ivory you encounter and that tells you where in Africa it’s come from. That enables you to focus some of your anti-poaching efforts in that area but also it give you more insight into how these gangs might be operating?

Sam - Yes. We identified the major poaching hotspots in Africa and Africa’s a big place. You can fit five United States in there, for example, so being able to say the majority of the really big cartels or transnational criminals are operating in two places is very important.

But the other thing that happened in the process was we had a very interesting breakthrough, when we’re sampling these seizures there could be 1,000 or 2,000 tusks in there and we don’t want to sample all of them so we developed ways to subsample them. The first thing we do is try to find the pair of tusks from the same elephant so we can remove one and not analyse it, but we noticed that over half the tusks in these big seizures didn’t have a pair.

Then I started wondering well where’s the other pair? I started looking between seizures and I found that very often when poachers are poaching, they’re selling it to a middleman, moving it to the big cartels and often the two tusks get seperated and they get shipped out in successive shipments. We were able to track those and to show that whenever you get two tusks going in seperate seizures, they’re always going through the same port, close in time, and the distribution of ivory in those are always highly an overlap that suggests the same guy is actually packing both seizures and you get a whole linkchain of matching pairs of seizures that link you back to the same cartel. In doing that, we’ve now been able to identify the three biggest ivory cartels in Africa.

Chris - Has that actually made a difference? Have you actually achieved any success stories in terms of convictions and so on and making a dent in this trade off the back of that knowledge?

Sam - Absolutely. The first conviction we got was in Togo in West Africa. A man named Emile N'bouke who was believed to be one of the largest traffickers in West Africa. He was convicted; he got the highest sentence that Togo offers which, unfortunately, was two years and he’s already out, so that was a bittersweet story.

Most recently, the biggest trafficker that we helped bring down - of course a lot of people were involved in this - was Feisal Mohamed Ali, who was convicted for 20 years in Mombasa. We connected him to 13 different large ivory seizures and that was pretty remarkable.

We have another person in custody now in Entebbe, Uganda. He has been linked to three other major seizures but he keeps postponing his trial, or someone does.

The other thing that is really kind of alarming is there have been a number of cases now where some seizures that we have identified that are incredibly connected to many other seizures. Two of them in particular: one never went to court; the other one was found not guilty which was - I can’t even say how shocked I was that that happened, so yeah.

Chris - Have you ever been threatened or do you worry?

Sam - Sometimes. But not really that much. I have been threatened but, you know, I’m passionate about what I do and I don’t really think about it to be honest.

40:35 - Down at the "Dead Shed"

Down at the "Dead Shed"

with Grant Miller, Border Force

The illegal wildlife trade is hugely linked with how easy it is to transport goods between countries, by land, sea or air. Any wildlife trade is under the control of international organisation, known as CITES; not all of it is illegal, but there are strict rules on what you can and can’t move into another country. So how do you catch what’s allowed and what isn’t. Georgia Mills went to Heathrow airport in London to visit Grant Miller, from border force and head of the National CITES enforcement team. They took a look in the so-called “Dead Shed”, a room full of all the illegal natural products people have been apprehended with at Heathrow. Some people may find this content upsetting...

Grant - You’ve got your timbers there. Elephant products, skulls, taxidermy. Your reptile skins; snakes. Medicinals: so from your traditional Chinese medicinals through to the New Age health supplements that we now get. And then a growing trade for us is the retro coats, so all the fur coats, etc, that used to come up.

Georgia - Is that a polar bear there, and a tiger?

Grant - It is a polar bear; that came in from Norway about 18 months ago. Then we have a piece of Indian red sandalwood. Two tons of this was smuggled through Heathrow airport wrapped up in…

Georgia - Two tons; sorry?

Grant - Two tons.

Georgia - Through an airport?

Grant - Through an airport in our freight facilities, wrapped in carpets - that was the smuggle. Moving through to ivory; the whole elephant is protected not just the tusks so what we do pick up is everything from elephant hide - that’s the skin of an elephant that’s been tanned and cured. And again, what they’ll do with that is they’ll make it into shoes. There’s a briefcase made from one. The tail hair made into a bracelet. A piece of handicraft bracelet. Then we have the ivory itself. Items that are being traded are statues, we have shaving brushes. We’ve got works of are, a little ball there that you can’t deny it’s a beautiful thing, it’s just the product is no longer acceptable for many, many people.

Georgia - Is that a monkey head as well?

Grant - That is a monkey head. Again, this was from a fairly recent conviction, and what we see with primate parts is that these are byproducts of the illegal bushmeat trade. So the hands, the skulls…

Georgia - Oh, that’s grim. That’s a necklace with a monkey skull on the end.

Grant - It is indeed. A crab eating macaque monkey skull, we believe, are traded and they are sold on online auction houses as gothic art. Holiday souvenirs - still a problem. The UK population still hasn’t got the message that it’s not acceptable to go abroad and bring back a stuffed sea turtle.

...Other products we’ve got: this is bear bile.

Georgia - Bear bile?

Grant - Bear bile. Again, the bear is held in horrendous conditions. A sealed cage invariably, a tap is inserted into the gallbladder and then the bile is drawn off. The bear can’t really move about: they go blind; they suffer from mental health issues; it’s tortuous. Vietnam at the moment is doing some fantastic work in actually trying to combat it’s bear bile trade. Again, a lot of the state’s provinces in Vietnam are incredibly proud now that can say we are bear bile farm free. A long way still to go; there’s a lot more work to be done but there is progress.

Georgia - Looking at this, what I’m quite blown away by - it’s quite a horrific stash - but there’s the things you always associate with wildlife trade. There’s the ivory horns and enormous bear skins but then there’s a lot of stuff here that I wouldn’t look twice at, so I guess it just shows how easy it would be to be complicit in this kind of thing if you’re not aware of what you might be buying and moving?

Grant - Absolutely. A tiger skin you would hope most people would be aware of. There are 33,000 species listed on CITES which are requiring our protection. The largest percentage of those are plant based. The best advice for your listeners is if you’re not sure, as the question before you buy it. If you move it over an international border and you don’t have the correct paperwork, you are committing an offence.

Now, in the United Kingdom, on conviction that could lead to a sentence of up to seven years and an unlimited fine. The largest sentence we’ve had historically is 6½ years so the potential for prosecution for yourself, to find yourself in real difficulty is there. My team; we make about 1,200 wildlife seizures annually, within that we will probably seize 1,000 endangered animals.

When border force seize and animal it becomes Crown property so the Queen has no idea the animals that she actually owns, but we have large amounts of those rehomed in zoos, both in the UK, but globally as well.

Georgia - So how do Grant and his team catch the illegal stuff coming through? Apart from studying who is flying in from where, and targeting flights from countries with species of interest, a big part of it is looking out for something that just doesn’t seem quite right…

Grant - What we have stuffed here is a dwarf Nile crocodile; one of the most endangered crocs in the world. We had six of these that were smuggled in through Heathrow Airport in transit to Korea. They came out of Benin and declared them as Mississippi alligators, so the common ones you would see in Florida and Louisiana, etc. That made us immediately suspicious because the last time we looked in Benin in Africa there wasn’t a population of these.

We had these six and we went out with our colleagues from the City of London Corporation and identified immediately that these were actually Nile crocodiles. Within 24 hours, we had lost two of these crocodiles - they died.

Georgia - Oh, the came in live?

Grant - They came in live, yeah, yeah, absolutely. What we found was that they had left the fishing hooks in the crocodiles so these were wild taken crocs. Bit of chicken on the end of your rope, throw your hook in, took it, and all they had done is cut the rope off. Again, working with expert vets in the UK, we were able to save the other four.

This is a rhino horn. It was smuggled in a plaster cast that was painted as a Spanish lady. If you look in the back there the little red and blue, that’s part of the cast that this was encompassed in.

Georgia - So they hid inside a model?

Grant - They did: inside a model. It was in in freight, that’s where we picked it up. The first question our officers questioned was why would you want to ship that plaster cast around the world because it’s like a child’s statue. Badly painted; not very good. So we X-rayed it and then, clearly, the rhino horn showed up within it. We broke it open and we found it.

Now, as well our targeting, we also have a couple of friends that help us. We have two wildlife detector dogs within the UK who have the ability to go out on a daily basis and detect wildlife products. Dogs have been really successful; they can pick up on ivory, rhino horn, furs, feathers, live tortoises, reptiles. We’re training them on corals at the moment and they’re deployed fairly effectively within the UK on a daily basis.

48:14 - Can we reduce the demand for animal products?

Can we reduce the demand for animal products?

with Sabri Zain, TRAFFIC

However much you try and prevent poaching and trafficking, none of it would be happening if there wasn’t a huge demand for these products. So can we reduce this? Chris Smith and Georgia Mills were joined by Sabri Zain, Director of Policy at the wildlife trade monitoring organisation TRAFFIC.

Sabri - Demand for ivory and rhino horn and other products they’ve existed for years for a variety of uses, whether it’s for traditional use or ornamental, but the challenge now I think is a far more complex issue right now. Markets are changing and a lot of these countries now have booming economies. With rhino horn for example, it’s not just traditional medicine now, it’s also used as a hangover cure, or it’s used for corporate gifting so there are a lot of psychological reasons behind the demand. Our approach to reducing this demand has to be a lot more sophisticated.

Chris - What do you do to try and change the behaviour of the men, women, and children on the street?

Sabri - This goes beyond awareness raising through posters and TV spots because, as I said before, we are not just at looking at traditional usage, you’re looking at people’s lifestyles, people’s attitudes and motivations.

So to address that problem we really need to understand the consumer down to the psychological traits such as what are the motivations, beliefs, attitudes of this consumer towards this product, and what can we do to change that behaviour?

The person may be buying an ivory tusk as a corporate gift. We’ve been working with Chinese auction houses, for example, who are offering animal themed figures in amber, in jade which would make a splendid corporate gift so you don’t need to kill an elephant to get the status that you seek.

Georgia - So once you understand why those products are being used it becomes much easier to then try and change behaviour. Where does this message need to come from?

Sabri - We’ve done a lot of studies which shows that the last person this message should come from is a conservation NGO such as mine. Because a lot of these consumers will say oh, you’re conservation NGO, of course you’ll say that and they’re not going to believe you, so we really have to make sure that we get the right messengers.

Celebrities work with a wide audience, but what we’ve found is that, for example, a lot of the corporate gifting, a lot of the career advancement, motivations of these people we need to use business leaders who these people look on as models saying no, this kind of behaviour is not acceptable and they will model themselves to that.

Chris - What’s the level of commitment at the top level - government level - to actually do this kind of thing? Are countries motivated to help in this mission or, actually, don’t they care?

Sabri - I think people now recognise that if you don’t address the demand that is driving this trade while traders will find whatever way the can to circumvent the law, and I think there’s a growing recognition of that. The UN General Assembly resolution on wildlife trafficking that was adopted in 2015 highlighted demand reduction as an important issue and CITES had its first ever resolution on demand reduction as well. There’s a major conference being held in London in October this year. Heads of State are going to be there. This high level commitment is very important to making sure that action on the ground happens.

Chris - Do these organisations actually have teeth? Can they do something?

Sabri - CITES certainly has teeth. Not only is it a legally binding treaty but countries that do not comply with CITES provisions face trade sanctions in CITES listed species. So, for example, last year Thailand was under threat of a CITES sanction, if they did not address their illegal ivory problems and CITES trade sanctions for Thailand would result in billions of losses for example their orchid trade. So CITES does have teeth but I think CITES also can provide the support, the expertise, the knowledge to help these countries address these problems.

Chris - Has all this been successful? Are you seeing the direction of travel if you like being in the right direction?

Sabri - One of the most significant conservation successes of the last year was China imposing a ban on its commercial ivory trade; that is going to have a huge impact. Three years ago, if you told me that China was going to ban its ivory trade I would have said whatever you’re smoking I want some.

That’s not the end of the story. It’s going to have a huge impact but it can also move the market elsewhere, so countries really need to follow suit so as not to undermine the successes that we’ve found in China.

Chris - Just bringing you back in, Sam Wassar, you’ve been listening to that. Does this give you cause to be enthused, do you think things are going in the right direction?

Sam - I think we’re still in a pretty scary place myself. I think that a lot of countries are not doing all that they can in this situation. I think that sometimes things are not what they seem and I’ll just give you an example with China. It’s wonderful that China has closed down their markets but when you look at all of the ivory that is being seized each year, in my opinion there’s far more than what’s ending up in the markets.

What I think is actually happening is some very wealthy people are buying these large whole tusks and they’re stockpiling those and waiting for conditions to open up again, perhaps if elephants go extinct, and then they will make a fortune. When that kind of thing happens all of these fixes are complicated and that’s not to say that we don’t need everything, we clearly need demand reduction. Demand reduction is the way that we keep those individuals that are stockpiling being able to profit from it but, until that happens, it’s very very complicated.

Georgia - Going forward there’s this conference coming up, what change would you like to see implemented?

Sam - Again, I’m a big proponent of demand reduction. The one problem I have with it is I think it’s too slow because we are killing so many elephants. If we’re killing 40,000 a year and there’s 400,000 left we have an urgency, and when we take a large seizure and we genotype it and get this information from it, it’s so valuable what it tells us about how this trade is operating, who’s connected.

One of the biggest problems is that we get these seizures very late. We get them one, sometimes two years late and, what we need to do is we need to make these countries understand how important it is to give us access to that information as quickly as we can so it has the maximum law enforcement action tied to it.

Georgia - Sabri, would you agree? What would you like to see in October?

Sabri - I absolutely agree with everything that Sam’s said. We’ve seen incremental progress, incremental change, but we really haven’t seen this push towards the systemic problems that are causing illegal wildlife trade: corruption, poverty, ensuring that there’s a strong local community engagement and buy-in into anti-poaching activities. I think what the conference would benefit greatly from is looking at those broader themes. Looking at not just seizing ivory but looking at financial crime; following the money where the kingpins are. There’s still not enough of that being done and engaging the private sector. The transport companies, e-commerce companies, and especially online technology companies because as these physical markets are being shut down around the world that’s where all the wildlife traders are going to. They're going online, they’re going to social media and I’m not sure we’re ready to tackle that and we really have to be prepared.

How big before a fall will kill an animal?

Katie Haylor put this perilous pondering to physicist Stuart Higgins from Imperial College London...

Stuart - There is no clear answer on size threshold of animal before a fall will kill it. There are so many different physical and biological factors that can affect what happens during a fall that it's no one number that gives us the answer. However, physics can tell us more generally about why smaller animals such as cats are more likely to survive the same high fall as a human.

Katie - It’s all to do with momentum. Momentum is your mass times your velocity – how fast you’re going in a particular direction. The bigger your mass, the bigger your momentum at a given speed. Back to Stuart, and the hypothetical animal that’s just fallen out of a building...

When you stop, there’s a change in momentum, and that means you’re experiencing a force. The size of that force depends on how quickly you stop. If you can increase how long it takes you to slow down, the force is less. This is how seatbelts, airbags, and the crash mats used by stunt performers work.

Stuart - Cats and squirrels have smaller masses, so even if they’re falling at a similar speed, they won’t experience as large a force as a human would. Cats are also particularly smart, because they can twist their body mid-air, to allow them to rotate and land on their feet. They can then use their legs like shock-absorbers to again increase the amount of time it takes for them to slow down, and reduce the amount of force on their bodies.

Katie - As well as cats, Matt’s question mentions squirrels. But take a flying squirrel for instance. Its blanket-like body shape when all stretched out gives it an edge when it comes to surviving a fall. After-all, they are able to glide through the air, as their shape results in increased drag, or air resistance. So where does air resistance come in to our question?

The bigger an animal, the higher its mass, and also the larger its surface area. ( It’s surface area that affects air resistance, like with our flying squirrel.)

But as you get bigger and bigger, the mass increases at a much higher rate than the surface area, and so it's the ratio of surface area to mass that means that smaller animals have a lower terminal velocity (the fastest speed they can possibly fall at) than larger ones. So a flat, light animal would fall slower than a narrow heavy animal. So how fast an animal will fall could be affected by its surface area, but how much of an impact this has depends on how heavy it is.

So whilst its difficult to say how big an animal would have to be before a fall would kill it, mass and body shape can influence how you’ll fare in a fall. Of course, animals that spend their life jumping or gliding around may be better at falling safely than most, and if you’ve got wings, well, that’s just cheating. Thanks Stuart!

Next time, we’ll be battling the elements with this cold conundrum from Mike:

Mike - When I cycle my bike in cold weather my nose runs, it doesn't happen in warm weather. Why is this? And is their anything I can do to help with it?

Comments

Add a comment