Have you been hacked? This week we examine the risks from public WiFi, why the Internet of Things is jeopardising the security of your home, the threats frequently lurking inside innocent-looking documents, what your mobile phone says to cybercriminals without your say-so and the new method of marketing: you compromise your competitor's website. Plus, in the news, an update on ebola, do bereaved people really die of a broken heart, and DNA points the finger at a Jack the Ripper suspect...

In this episode

01:18 - Why is Ebola spreading so quickly?

Why is Ebola spreading so quickly?

with David Pigott, University of Oxford

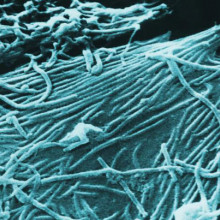

With over 3000 victims so far, the EBOLA crisis gripping parts of West Africa is TEN times larger than any previous outbreak since the disease first surfaced over 40 years ago. Scientists also speculated this week that up to 20,000 people might be affected before the outbreak peaks. So why is this happening? According to a new study, it's because the human population, communications - including roads - and peoples' travel patterns in the affected countries, have changed dramatically in recent years, and this is driving the spread. Even more worrying is that the new study also suggests that, in total, 22 African countries could be at risk from similar ebola outbreaks. From the University of Oxford, David Piggott...

David - Given the recent outbreak in Guinea, we've been looking at how Ebola is actually spread around the African area. So, when you consider Ebola, it's important to recognise that there are two distinct processes going on. firstly, there's what we call the zoonotic phase where there's cycling of Ebola viruses between animals. We currently think that bat species are the main reservoir of this, but also, great apes such as gorillas and chimpanzees can also be infected. Occasionally, humans interact with this animal population normally through bush meat hunting or butchering of animal carcases. And then it transitions from animals to humans and then there's subsequent human to human transmission going on. So, in the outbreak in Guinea at the minute, genetic evidence have shown that there's only actually been one transmission event from animals to humans and that all subsequent cases are actually human to human interactions so burial practices or caring after the sick relatives for instance, or within the hospital setting itself.

Chris - What can you tell us about Ebola's history because this is not a new infection? It's been knocking around and periodically surfacing for a number of years, hasn't it?

David - Yeah. So, it's got about a 45-year history. In 1976, there was a series of unexplained symptoms and never really been recognised before that occurred simultaneously in what was then called Zaire - Northern Democratic Republic of Congo and also, in the southern borders of Sudan. And since then we've seen small numbers cases, no more than 400 to 500 individuals involved in an outbreak and spreading no further than one or two imported cases elsewhere in the world. So, with the Guinea outbreak, what we've actually seen is something that seems completely different to the previous history of Ebola. We've had more individuals infected than all other outbreaks of Ebola combined and we've actually seen it spread to more countries than we ever have before. So, it's moved from Guinea to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and then through air travel to Nigeria and Senegal recently.

Chris - So, would you say then that the sort of dynamics, the way in which the disease is behaving in this outbreak are clearly different than patterns you've seen in previous years?

David - So, in the work that we've been doing, we've been looking at how the connectivity of these populations has changed dramatically over the last 45 years. The population size themselves has nearly tripled and actually, we only have international air connectivity data for the last 5 years or so. But within that period of time, some countries have actually increased their outbound flights by 3 or 4 times. So, it's a pretty rapid increase.

Chris - And why do you think that those things changing could increase the likelihood that Ebola will surface and alter the way in which the disease behaves in communities like it has?

David - All these human changes are actually going to be very important in how we see human to human transmission of the disease. So, increasing population size, increasing population density is going to mean that if individuals are infected, they're more likely to come across others to infect them.

Chris - So, how did you go about doing this study? How did you get the data that's enabled you to begin to look at how the disease might change or how there are various factors that could influence the dynamics of this infection?

David - So, we looked at the last 45 years or so of published articles on Ebola virus, both within humans and animals. Basically, it was a bit of detective work identifying human outbreaks and then backtracking it all the way to see who was the first person that got infected, and if possible, how they became infected.

Chris - What implications are there on the basis of what you have found in your analysis for both preventing future episodes and outbreaks of Ebola, but perhaps managing better the current crisis we've got?

David - So, there's two different aspects to that. I think one of the most important things that our paper shows is that the range of different countries that are at risk of Ebola is actually a lot greater than we first thought. So, we predict that there's 22 countries in Central and Western Africa that there's the environmental possibility that animal to human transmission can occur. Seven of these countries have actually seen that transmission occur, but there are 15 countries that haven't actually seen Ebola in those areas. So, these will be great places to start surveying bat populations or other mammals that could be reservoirs of Ebola, i.e. animals that are infected with Ebola, but don't show signs of infections so they don't die necessarily. To get a better understanding of how the disease is cycling within animal populations and that's a very important process to understand because then it allows us to assess the risk or 'does hunting in this area actually mean that the transmission from animal to human could occur?'.

Chris - Now, given that you've identified that the potential for Ebola outbreaks is much bigger than the present pattern of activity, what sorts of strategies would you urge apart from obviously monitoring to try to prevent this happening in the future or to get a handle on where it might happen and mobilise some sort of resource to stop it?

David - So, I think it would be a very tall order to try and say or the next area where Ebola is going to transition from animals to humans is going to be. But one thing that we could do is look to see how these populations are connected. So, there are some people that use for instance mobile phone data to see how people move within a country. So, if we can identify areas that are very well connected, we could perhaps prioritise those transport nodes as it were to prevent further spread of any infection should it actually occur.

08:20 - Can you die from a broken heart?

Can you die from a broken heart?

with Dr Anna Phillips, University of Birmingham

It's remarkably common for elderly people - who were previously healthy - to die soon after their spouse. We usually say they've died of a "broken heart." But why? Could there actually be a medical reason?

Ginny Smith caught up with Dr Anna Phillips from the University of Birmingham who has evidence that it's down to the immune system not working so well at times of stress...

Anna - The study that has just come out is looking at the stress of bereavement which is a chronic stress because it's enduring and we wanted to see whether it could have a negative effect on particular parts of the immune system that are very key for fighting off diseases like pneumonia. There's a lot of anecdotal evidence - people are always saying how they had a relative who died suddenly and then in a very short time afterwards, the spouse of that person also died and they had been previously healthy. And we're interested in finding out why that might be. Are they dying of a broken heart or is something going on in the immune system? Is the stress of bereavement accelerating their own mortality?

Ginny - So, how did you go about studying that?

Anna - We had some great collaborators at St. Mary's Hospice who gave out our information to the friends and family who had lost people who have been staying in a hospice. These individuals were able to decide if they wanted to take part in our study and if they did, we would give them a questionnaire and also take a blood sample so that we could look at immune function.

Ginny - And what were you looking for in that blood sample?

Anna - We were particularly interested in a cell called the neutrophil. So, it's an immune system cell. There's a lot of them and they're very important if you're fighting off pneumonia. So, they're very important for older people because pneumonia is a big killer of older people. What the neutrophil does is it engulfs bacteria or 'eats' them and then it produces a lot of chemicals such as reactive oxygen species that actually eradicate the bacteria. So, we particularly wanted to look at this cell because this is the one that if it's not working, an older person is going to be susceptible to infection and death from pneumonia.

Ginny - And what did you find? Was there a difference in these cells for the people who've been bereaved?

Anna - When we compared bereaved old adults to a control group, so these are people who are non-bereaved, relatively healthy, older people, we found that the bereaved people had poorer neutrophil function. So, while their neutrophils were still able to engulf bacteria, they just couldn't kill it effectively. They weren't producing as much of these reactive oxygen species. And the interesting thing was that we compared this to a younger group. And although the younger bereaved group also had high levels of stress having suffered bereavement and had high anxiety and depression, their immune cell function was fine. Their neutrophils were working the same level as a young control group. So, it's the older bereaved people that were susceptible to poor neutrophil function.

Ginny - So, what do we think is going on here? Why is it having more of an impact in the older people than in the younger people?

Anna - As you age, your immune system ages as well and it's what we call immunosenescence and there are changes to various parts of the system and also, to the function and numbers of different immune cells. So, by the time you're 65, your immune system isn't working as effectively. That's why we see things like poor responses to vaccination in older people and higher levels of infections. When you add a chronic stressor on top of that, something like bereavement, that's when we expect to see that older people would be even more vulnerable because their immune system is already not working as efficiently as it was when they were younger.

Ginny - And do we know what it is in the body that's controlling this change in the immune system after a stressor?

Anna - We think that one of the key mechanisms that might be having this impact are stress hormones, so for example the stress hormone cortisol, which can be a good thing because it's anti-inflammatory, but also can be a bad thing because it can supress the function of some parts of the immune system. When you have a chronic stressor, you have more cortisol generally in circulation, but you'll also have a drop in the opposite hormone which is dehydroepiandrosterone or DHEA. Now, this also decreases with age. So, by the time that you're over 65, you don't have the same levels that you had when you were younger. And the interesting thing is the ratio between the stress hormone cortisol and the other one, DHEA, because DHEA is immuno-enhancing whereas cortisol can supress immunity. And what we found is that the bereaved people in our study, the bereaved older adults, had a higher ratio of cortisol to DHEA.

Ginny - Is that having an impact on them? Are they more likely to feel sick because of that?

Anna - Certainly. If you've got a high cortisol to DHEA ratio, that's been related in other older groups to having an increased risk of infection and also, mortality from infection. So, we believe that the changes we're seeing here will have real knock-on effects. If you're not able to combat pneumonia for example then yes, that's going to have a big impact on your health.

Ginny - So now we know this, what can we do to help people who are vulnerable to these kind of effects?

Anna - We could try and correct the hormone balance which hasn't been done yet, but we are considering looking into whether a supplement, such as trying to get people's DHEA levels back up to where they were. Just for a short time, it might actually help them, but there are lots of simple ways as well. So for example, one of the ways that you can boost your immune function and boost your DHEA levels is by exercising, even if it's just moderate physical activity. And also social support. It's really important at times of stress like bereavement, to have a social network that you mobilise. Don't be socially isolated because you'll be at more risk.

Kat - Birmingham scientist Anna Phillips speaking with Ginny Smith about the work she published this week in the journal Immunity and Ageing.

13:52 - Jack the Ripper's identity discovered?

Jack the Ripper's identity discovered?

with Jari Louhelainen, John Moores University and Russell Edwards, author

In the late 1800s, a killer stalked the streets of London. He was dubbed 'Jack the Ripper' but his real identity has been a source of speculation ever since.

Now, an author and a scientist working together have used genetic techniques to apparently confirm his identity. Their work builds on suspicions that the ripper might have been a Jewish immigrant called Aaron Kosminski who had fled persecution in Poland with his family to Mile End in London in 1881. But no one would testify against him and to date, no one has ever been condemned or convicted for the gruesome murders of at least 5 East End women.

But writer and Ripper enthusiast Russell Edwards tracked down at an auction in Suffolk, a blood-stained shawl that were said to have belonged to one of the victims - a woman called Catherine Eddowes. Russell then hunted down Liverpool-based John Moores University scientist Jari Louhelainen who specialises in recovering DNA from old artefacts. He was able to extract one of the forms of human DNA present in our cells called mitochondrial DNA from stains on the shawl which included blood from the victim and semen stains left by the ripper. And he then matched those DNA profiles to living descendants of both parties. Strongly suggesting that Aaron Kosminski was the ripper. Chris Smith spoke to Jari Louhelainen to hear how he did it.

Jari - The DNA testing started slowly because we have to avoid surface contamination. So, material which was on the surface like someone touching the shawl and all kinds of debris like even dandruff and so on. So, it took some time, but in the end, we managed to extract a DNA sample of these stains. So, in any object or surface, DNA falls apart with age. So, in order to see the big picture, we need to put these bits back together like a jigsaw puzzle. That enables us to read the complete sequence. After this, we could then compare this to the descendant's DNA and verify that the object belonged to one of the murder victims. In the beginning, we didn't have the descendants so we had to track this person down and we thought it would be nearly impossible. But Russell had seen her in a BBC programme by accident. I think it was Find My Past.

Chris - So, you get DNA from this surviving descendant of this person who was killed by Jack the Ripper allegedly and you get her DNA profile and then compare it to what comes off the shawl.

Jari - Yeah, that's it.

Chris - And what do you find?

Jari - It was a perfect match as long as we could see. So, this is mitochondrial DNA. Similar to this is for example, Richard III case where they used in the same way mitochondrial DNA. So, that gave us enough confidence that we could continue this where it's beginning to look like that indeed it belonged to the murder victim.

Chris - Indeed, it proves that this shawl must've been in contact both with the victim but also potentially, in contact with the person who did the crime.

Jari - Yeah and that was the hard part. I thought we are done here until I found some stains which looked like a sperm or semen stain. I couldn't understand why these are here as well and I told this to Russell and his eyes lit up and he said this is exactly what has been reported about Jack. This is his way of operating and this is a great find.

Chris - So, what you're saying is there was a sexual element to the crimes he committed and that this was some evidence of that left behind.

Jari - Exactly. Now, at this point of course, we don't have any material from these stains. So, we started hunting that and I'm not an expert on that so I asked my friend at the University of Leeds, Dr. David Miller to have a look. He didn't find the sperm heads but found the epithelial cells which are associated with the sperm head. Just a very few of them and they were in bad condition.

Chris - Did that yield DNA nonetheless despite the poor condition? Did you get DNA from that semen stain?

Jari - Yeah.

Chris - So now, you're in a position where you've got a shawl which has the genetic markings associated with the person who was a known victim of Jack the Ripper. You also now have bodily fluid remnants which are consistent with this guy's modus operandi, how he was alleged to have killed his victims, and you can get DNA from it. So, that still leaves an unfinished part of the puzzle which is that you've just got a DNA profile from a stain. How do you know that this stain comes from the ripper himself?

Jari - Well again, this was one of these things that we have to find the descendant. I thought that even if we find this person, it would be impossible to sort of get a permission to use her DNA. Russell then tracked this person down with the help of genealogists and he managed to get this person to cooperate. So, what we used was mitochondrial DNA and we also got the genomic DNA from the cells which were associated with the sperm heads and managed to get the hair and eye colour.

Chris - In other words, you get a genetic match with the surviving descendant of Jack the Ripper. How much certainty do you have that this is what you think it is?

Jari - So, this work is based on mitochondrial DNA in both matching the victim and matching the suspect. So, this is not valid in modern court, so there's some bit of uncertainty in that sense about the same level as with the Richard III case where they use also mitochondrial DNA. What we have is strongly suggesting that this is the case and I think Russell is using my DNA work and his own sort of circumstantial evidence to say very firmly that this is 100% conclusively Aaron Kosminski. But my DNA work actually just gives a strong suggestion at this point and it needs to be verified.

Chris - John Moores University scientist Jari Louhelainen who worked with author Russell Edwards on naming Jack the Ripper which is also the title they've chosen in publishing their book to tell the story.

20:17 - What makes the perfect cup of coffee?

What makes the perfect cup of coffee?

with Liz Booker, Starbucks, and Alex Monro, Natural History Museum

Coffee now and the chemistry behind your morning fix. Scientists have now sequenced the genetic code of the coffee plant to help them work out why really great coffee tastes and smells the way it does. Graihagh Jackson went to meet coffee connoisseur Liz Booker, from Starbucks, and botanist Alex Monroe, from the Natural History Museum...

Alex - There are about 68 to 70 species of coffee of which probably 8 have been used  for producing a beverage. Most of the current coffee market would be Robusta which is one of the species and Arabica which is the one probably most people are familiar with.

for producing a beverage. Most of the current coffee market would be Robusta which is one of the species and Arabica which is the one probably most people are familiar with.

Graihagh - So, what sort of benefit does genome sequencing have?

Alex - It provides us with a whole suite of tools for us to tease apart how the plant generates the chemicals which are represented by that flavour and then you can start looking at ways of identifying the genes you think are responsible for flavour, and then you can go and look for those genes in lots of different individual plants growing all over the world.

Graihagh - And one thing they looked at in particular there I thought was interesting is, how caffeine had evolved in plants. Why are all these different varieties evolving to have caffeine in their leaves, in their fruit?

Alex - It's basically assumed that that chemical is produced to defend the plant from probably, insects.

Graihagh - We're sitting in Starbucks and with me is Liz Booker. Liz, you're the chief coffee taster for Starbucks. What makes the perfect cup of coffee? I mean, we've talked a bit about how there's lots of different interesting flavours. Is it all down to the genes or is there more to it than that?

Liz - There's much more to it than that. So, you want to start off with a really great coffee plant and a really great seed which is the coffee bean. But then there's a huge amount of care and attention that you need to pay to the plant as a farmer, to be able to develop a tree that's going to bring you really fantastic beans. And then from growing really brilliant beans, you need to be able to pick them exactly at the most perfect time. And then you want to be able to process those coffee beans in the best way to bring out the flavour attributes of that coffee.

Graihagh - Can we try some?

Liz - Absolutely. So, what I brought for you here is a cupping and this is the professional way that we taste coffee at Starbucks when we're deciding whether or not we're going to purchase it. The first thing that we're going to be looking for is the aroma and there are about a thousand different kinds of aromas coming out of Arabica coffee.

Graihagh - So, we've each got one spoon - Alex, Liz and I.

Liz - First of all, we're going to break the crust. So, we've got hot water and ground coffee in these little glasses and there's a thick crust. The crust of coffee forms at the top. With this, we're actually going to break the crust and smell all the aromas in the coffee. So, first one that we're going to smell is the Zambia Terranova coffee.

Graihagh - Smells quite earthy to me. It's my initial instinct. What do you think, Alex?

Alex - It smells very warm and aromatic. It smells like coffee.

Graihagh - Smells like coffee. What can you smell?

Liz - For me, I'm getting a little bit of nectarine and peach, and then a little bit of vanilla as well. It's also got some really soft spiciness, a little bit similar to nutmeg for me. You want to grab a spoon. I'm going to show you how we taste the coffee professionally. So, you take a spoonful of coffee. The next thing that you have to do is slurp the coffee. The reason that we slurp coffee is we want to get all the coffee up into our sense of smell. It's the noise that your mum shouldn't be proud of you making.

Graihagh - It's a very fierce slurp. Okay, so this one is the Zambia one.

Liz - It's a little bit like whistling backwards. So, if you can whistle and then think about reversing it then that's how you get a really good slurp. You should be able to pick up some of those really beautiful bright juicy notes.

Graihagh - Given that there's so much at play here when you're tasting coffee, do we really need another variety?

Liz - I think definitely being able to work out how to get plants that are stronger, being able to have plants that are going to be more resistant to disease will ensure that farmers are able to produce really high quality crops and then develop really gorgeous flavours within them. So, I think that would be fantastic for the farmers.

Kat - That's Liz Booker and Alex Monro, slurping along with Graihagh Jackson.

Chris - Kat (slurping), do you know what that is?

Kat - What is that? A cup of tea.

Chris - PG tips. Did you get the delicate notes in there?

Kat - Only the delicate noise of your slurping, Chris.

25:02 - Is your Internet security up to scratch?

Is your Internet security up to scratch?

with James Lyne, Sophos

Our lives are moving increasingly online. Tax, pensions and benefit claims are handled over the Internet. We pay bills, buy things, do banking, and Royal Mail is rapidly being replaced by e-mail. These communications often contain sensitive personal data. But how safe is it? Security should start at home. Unfortunately, it turns out that many of us are blissfully unaware that we're leaving ourselves very exposed. James Lyne is the Global Head of Security Research at Sophos and he set up a project called the World of Warbiking to show just how vulnerable we are...

James - The World of Warbiking was a bit of a mad science project that we came up with to go and measure just how well we, in society in general, are doing at securing things like our wireless networks that we're all increasingly depending on for business and of course, most of the time at home. So, we took a bike, fitted it with some special wireless scanning equipment, some minicomputers and some batteries and solar panels - very Heath Robinson - and cycled around 5 major cities around the world, building a map of the wireless networks that we all use. Really, to cut to the spoilers, I can tell you that across each of those cities, between 4% and 9.5% of the population of those cities, we're using wireless security standards that have been known violated and broken in less than 60 seconds by the hackers since 2004. Shocking!

Chris - So, you're basically riding around in a bike and the bike is rigged up with a system that will probe without hacking into them, just probe and ask the simple question, what wireless networks are here and what security protocols are they running, and you're therefore assuming because we know how vulnerable various networks are, that those people have got no other security.

James - Precisely and with a small number of willing victims that signed off, we actually did demonstrate the ability to break those networks in less than 60 seconds and show them their own passwords. And what was very amusing was of course, most people didn't know their own password and had to go and look at the sticker they put on the fridge which is an entirely different security issue.

Chris - Which cities did you look at?

James - So, we did London, San Francisco, Sydney in Australia, Hanoi - cycling in Hanoi was very interesting. And wrapped it all up with Las Vegas which was a particularly interesting area I must admit. We had a little extra dimension to this experiment. As we were cycling around, we had our very own wireless network which we offered to members of the public. If you connected to our network which was named either Free Public Wi-Fi, Free Internet or Do Not Connect ( that was my personal favourite), you would be offered internet access, you'd be given a warning and then we logged what people got up to and how secure they were. I can't even go to the details of what some people were browsing in Vegas, but suffice to say that overall level across the different cities, a less than 1.2% of all the people that connected to our wireless network, thousands and thousands of people were appropriately securing themselves to protect themselves against us deploying malicious code, intercepting their emails, instant message chats, or alike...

Chris - So, you've got people connecting to a network called Do Not Connect and what are they doing? They're online banking or something?

James - Actually, yeah. The number one activity was online banking. I mean, what could possibly go wrong by connecting to one of these networks? I'm sure that's fine.

Chris - And 99% of them are vulnerable. The people who do that are not using any kind of security measure. That means that were you interrupting those transmissions and siphoning off the data on the way to the bank and they wouldn't know about it, they wouldn't be able to stop you.

James - Yes, that's absolutely correct. What's really depressing is, the technology to stop this and the simple behaviours to prevent these kinds of attacks has been widespread and well-known to the security community for many, many years, most people simply aren't doing it.

Chris - The other thing which I think perhaps we should dwell on is, going back to your fact that maybe 10% of networks whether they're in businesses or in public or Wi-Fi hotspots and things, less than 10% of them are using robust and resilient security. Surely, a bigger question is, what is behind those networks? What's plugged into them because increasingly, lots of devices now are on the internet. We've got this phenomenon of the internet of things coming along and this means potentially, if someone can compromise your home network, they're actually compromising everything you've got in your house.

James - You're absolutely right and it's a really interesting trend that has seriously taken us all by surprise. Just yesterday, I bought a slow cooker for my kitchen which comes with wireless built-in by default and connects to a smartphone app which enables me to turn it on from the other side of the world. And a little bit of reverse engineering, I've already found that it uses a static password which means that if I can find anyone else's slow cooker, I can control that as well. So, I might be ruining a few beef stews shortly. But that's of course just one of the many types of devices - baby monitors, CCTV cameras. I mean, I've even found wireless plant monitors that will water your plants for you whilst you're on holiday. I mean, we're really extending the reach of digital technology into the physical world and placing it all around us, which opens up a lot of possibilities for attackers.

Chris - Going back to the CCTV point, if people have got a CCTV at home extensively to make their house more secure and that's behind an insecure network interface and someone like you knows how to find those cameras then you could potentially actually turn it around. And so, well I now know when the people aren't at home because I can use their own camera to find out when their home is empty and then go rob it.

James - There's a deep-rooted irony there, isn't ther? These devices are shockingly poor. I acquired 12 CCTV cameras from Amazon - the kind that you would put in your home or a small business and I found serious flaws that would enable anyone with a bit of skill to get into every single one of them. I actually did a bit of searching online as much as we could within the confines of law and ethics unlike the cyber criminals. I found a petrol station. This petrol station has a feed over the chip and pin terminals which you use when you make payments. And it's high enough resolution that I could see all of the credit card numbers and the pin numbers being typed in. And that was streamed to the internet with no user name and password.

Chris - Good grief! Have you told them?

James - Yeah, I've actually managed to locate which I think is the right petrol station and I've sent them a note. The feed is still there, along with many others. I found an Italian clothing store that's wonderfully creepy as it has infrared in the changing room which I've emailed them and said, "I thought I was horribly inappropriate even it was a secure system" an astonishing number.

Chris - What can be done because your average person who isn't computer savvy, they use certain platforms that are very, very user friendly for a reason because they don't want to have to become an uber geek on a computer to overcome this sort of thing? What can they do? What can the average person do to make themselves safer?

James - I've got a very simple ask that there are a number of very simple best practice items, things like getting yourself good passwords, not using the same password on every site and service, keeping these devices up to date, check your home wireless network, and make sure you're using the latest security standard. I could use a bit of jargon here, but it'll be helpful so you'll know what to Google to get some tips. Look up wpa2 and if you're really, really unsure, ask an expert. If you can do those simple things, we'll make sure as uber geeks, along with lawyers, regulators and the like, that these internet things devices get improved.

33:42 - What your mobile says to criminals...

What your mobile says to criminals...

with Daniel Cuthbert, Sensepost

What is your mobile phone telling criminals about you? Daniel Cuthbert is from the UK and South African security company Sensepost.

is from the UK and South African security company Sensepost.

Kat - Now, I've just come back from 2 weeks off in the US, touring around, talking to some scientists and I have pretty much logged on to every free Wi-Fi network that's going. I'm starting to maybe get the feeling from the look on your face that that was not such a smart thing to do. So, what information could hackers get from my mobile phone and how could they do this by me using things like free Wi-Fi?

Daniel - So, I guess the short answer is a lot. The way that we use our mobile devices today has changed. We're no longer using a laptop or a PC to do online banking, online purchases, browsing our social media. We're using these mobile devices. Unfortunately with that, we're also using Wi-Fi. As James just eluded to, Wi-Fi is pretty much everywhere these days, from the internet of things to petrol stations, etc. And the promise of free Wi-Fi especially when you go abroad with roaming charges, what they are.

Kat - It's ridiculous frankly.

Daniel - It's almost criminal. It's quite nice to use. You can stop into your local Starbucks or your McDonald's or if you see something that says 'Free Internet'. Well, why not? I can just quickly jump online and check my PayPal balance, etc. The problem is, one, you have no idea who controls the information that's passing between your phone access point and to the rest of the internet. And there's no way of you really telling. And two, the information going out there could be your credentials, your Gmail account, your banking details and anything else that your phone sends out. Now, the problem is your mobile phones are quite chatty. So, when you connect to the internet, all your applications, all your social media apps all screaming out to everybody going, "Hey, I'm here. Give me some updates." And if there's some evil person sitting in between, there's a very good chance that they're getting that information too.

Kat - So now, I'm kind of scared. How could someone be doing that? How could they be intercepting? For example, I was in a Starbucks in Manhattan. So, how could someone - and I logged into Starbucks Wi-Fi - how would someone be intercepting what I was doing there?

Daniel - Are you sure it was Starbucks Wi-Fi?

Kat - It said it was Starbucks Wi-Fi and I got like the Starbucks thing came up.

Daniel - We're very trusting when it comes to the internet. It's one of the mediums that attackers exploit that just because it says Starbucks - well it must be. Traveling here on the tube, I passed a number of access points pretending to be Vodafone Wi-Fi. I have no idea it's controlled by Vodafone, but it says it's Vodafone. So, what attackers can do is they can pretend to be these networks because you're trusting. And there's a very good chance that you've connected to these networks before. So, it's very easy to do what's called a jargon thing, rogue access point, where I pretend to be another network and give you internet access.

Kat - And I guess like a lot of phones now, they'll automatically connect to something if they think they've seen it before.

Daniel - Yes. It's called 'Your preferred network list'. So, it's a usability issue. You don't want to have to keep on remembering say, "Right. I want to connect to Starbucks free Wi-Fi or Vodafone free Wi-Fi." Your phone goes, "Hey, I've seen that before. Let me connect to it." She wants to connect to the internet.

Kat - I'm still even more terrified. So, how likely is this to be happening to people? You know, so I've logged on to maybe - I don't know - 10 free different Wi-Fis in the past couple of weeks - or someone who's sort of every day, they're logging on somewhere. How big a risk is it really strictly?

Daniel - It's very hard to put a number to it. Two years ago, we released a piece of research that called Snoopy where we looked at this risk itself, how trusting are people. During our test cases, the vast majority of people did connect to our rogue access points and browsed the internet. And we were doing nothing illegal, but if we were doing it, there's a very good chance that criminals are doing it because it is actually quite easy to do. The benefits and the yields that you get from doing it are actually quite lucrative at the moment.

Kat - Is it just people saying 'you shouldn't obviously do your online banking if you're in a coffee shop', but how bad can something like checking Facebook be? Does that put me as much risk as doing say, my online banking?

Daniel - It does to a degree. Facebook is a good example. People are inherently lazy when it comes to the internet. So, we will re-use the same password because passwords are hard to remember. James mentioned having a good password, but on a mobile device, a really long, strong password is actually very hard to type in. So generally, you'll have one password and it could be the password for all your social media activities. So, if I can get that information and sell it on or contact your friends and say, "Listen. I'm stuck somewhere. Can I have some money? Here's my bank account details." Perfect scam gets used a lot today and a lot of people fall for it.

Kat - I've definitely had many of those emails. So basically, what can people do? So, we do need access to the internet whether that's through ridiculous roaming charges or through free Wi-Fi, how can I, and all our listeners, protect ourselves from these risks?

Daniel - So, there's a couple of things. It's not all doom and gloom. The first thing, stop being so trusting just because the network says it's free. Ultimately, think why is it free? What does it do with my data? And that's where the big money is being made today with your data. Secondly, if you are using something like online banking or other financial transactions, make use of a VPN.

Kat - What's that then?

Daniel - So, it's a virtual private network and effectively, what it does, it will encrypt your data from your phone, through to a trusted server and then onto the internet. So, it stops people eavesdropping on your communications.

Kat - And how would I find one of those? Can I just sign up for one?

Daniel - Yeah, Google - not free VPN. I'd go for a paid VPN again. Why is it free? What are they doing with the data? They cost on average, a couple of pounds a month. But if you are mobile and you do rely on your phone a lot, I'd honestly say, get hold of a VPN. At SensePost, we only travel and use VPNs when it comes to our mobiles.

Kat - So, given that I obviously don't have a VPN and I've just spent the past 2 weeks connecting promiscuously to as many Wi-Fis as I can, is there anything I could do to my phone, to check that I'm okay or should I be changing all my passwords?

Daniel - I think it's a good idea to change your passwords on a frequent basis anyway so now is probably a really good time. It's not a case of panic, "Oh no, somebody might have got my data."

Kat - But they kind of have already then I guess.

Daniel - Then run to the hills screaming.

Kat - And broadly, do you think it's really important that we do try and talk sensibly without panicking too much about these issues?

Daniel - Definitely. It's not all doom and gloom. The security industry does like to play down this stuff a lot, but I'd say listeners, common sense has to prevail here.

Kat - So, be safe and it's okay.

Daniel - Definitely.

Kat - Thank you. That's Daniel Cuthbert from SensePost.

40:42 - How hackers use email

How hackers use email

with Stephen Kho, Rob Kuiter, Vlad Ovtchinikov at the 44Con cybersecurity conference

Do you use your mobile phone to browse the Internet when you're abroad? If you do, you could be in danger of someone siphoning off your data. We'll hear how in a moment....

But first, email: if an email turns up from someone with a familiar name, and there's a document attached to it that seems to be relevant, or you work in recruitment and someone sends you a CV, you're likely to open it. But these documents are often phony and are a virus in disguise. And when you open them on your computer they deploy a malicious programme called a "payload" that hijacks the machine.

But these documents are often phony and are a virus in disguise. And when you open them on your computer they deploy a malicious programme called a "payload" that hijacks the machine.

Graihagh Jackson has been at the 44Con conference where she met Vlad Ovtchinikov who looks at ways hackers use to entice us to open malicious documents...

Vlad - These days, what attackers are moving onto is client side exploitation. It's when we deliver payload, not directly, not attacking the machine directly from the internet, but we deliver the payload which will infect the system through the email or other means.

Graihagh - So, I open up an email and how might you be able to infect my computer with malware?

Vlad - Well usually, scenarios are - we profile our targets carefully. We construct an email within the context of interest of business of the person we're targeting. In lots of cases, we use documents. It contains some smart code within it which will identify the system that it runs on and then it will execute the payloads and will provide us with a reverse access to your system. This is the primary distribution vector for banking malware.

Graihagh - So, it's literally as simple as opening up a Word document.

Vlad - Yes, it is. From my experience, we were successful, 95% success over that.

Graihagh - So, how do you convince people to open this document because we all know that you don't open emails from people you don't know, you don't trust, it might contain a software. People are aware of that. So, how do you convince them so to speak?

Vlad - It might be from a national organisation and it might be an email sent to you from a trusted address containing something that's tempting to open. It might be a payslip from the place or organisation. So, there are many different associated tricks to make you want to execute a document and run it.

Graihagh - So, to engage someone, you might say, my colleague 'xyz' salary or bonus and then meant that might be a good way to entice someone. I know I would be tempted to open up a document that said something like that.

Vlad - There are many different ways and techniques we can apply in order to persuade the potential victim to run it. Most of those documents are cleaned up so anti-virus systems that you have installed will not catch them.

Graihagh - So, once you have access, once you've opened that document, what sort of information can you gain through that?

Vlad - Everything. Everything that the user has access to, even more in some cases, we have more access and control over the box that the user has. So, full access to the user's workstations and the network environment around him.

Graihagh - What sort of examples do you have that might demonstrate the power of something like this?

Vlad - Malicious guys, based underground. so, they'll be able to fish out credit card details from your computers. They'll be able to see their memory. It will inject itself into the browser and will compromise everything you see on screen through the browser. It'll be able to capture any form submissions which you are sending out via HTTPS. It's called form grabbing. For example, you visit an HSBC webpage. Everything looks legitimate but before the browser renders up, the html will be able to inject some additional code into it, so whatever you see will be hijacked. There might be additional field added to it asking for your date of birth or your credit card number due to security reasons or whatever. So, everything can be done. Once you compromise the system, everything on the system as well as everything that sits behind it within that work environment is basically a open air.

Graihagh - I've learned a little bit about some of the security issues about what happens when you're at home and in the workplace, but what about when you're on your holidays? Well, I've just stepped outside the conference with Stephen Kho and Rob Kuiters from KPN to talk a little bit about what happens when you're roaming abroad on your mobile phone or tablet. Normally, when you're at home, you're browsing the web. That data goes straight to your network. But when you're traveling in another country, there's an additional network it has to go through and that network is the GRX. Now, you've both been looking at the security of this additional network GRX. But first Stephen, what sort of data are we talking about here?

Stephen - GRX carries the roaming data part. So, not the voice or your SMS text, but anything you do when you're browsing the internet for example. So, if you log into yahoo mail, Gmail, your Facebook, all data related goes through across that.

Graihagh - What's your work revealed?

Stephen - We discovered actually that so much of the GRX network equipments - so the servers and different systems - were fully out of date, misconfigured, missing patches. And so, with easily available hacking tools you could reach it and exploit those systems and then subsequently, you could capture this information.

Graihagh - What sort of information are we talking about? I know we say we've of logged into Facebook, but does it really matter that they've seen a few friends and I've written that I like that person's photo on Facebook?

Rob - I think there's more data carried across. It's not only your content, but also your credentials. So, you're using your passwords. You could access all these kinds of information on this network.

Stephen - On top of that, GTP which is the protocol information, that has your location details. It also reveals what sort of equipment you're using. So, if you're on an iPhone 5S or a Samsung S5, that sort of information is available which means that you can have a really targeted exploit against you if you were the person of interest.

Graihagh - So, it's not just generic sweeping data. It's actually data that's very, very personal to you. Surely, that's illegal. Surely, that shouldn't be allowed to happen.

Stephen - Well, that's very difficult to say because we don't actually know what kind of legislation or what kind of freedom these intelligence services have. But you can, if you want to, protect yourself by using a VPN solution. So, there are quite a few numbers of applications which you can install on your phone which encrypts your information from your phone towards a server. So, you have additional security measures there. It's more difficult for them to extract the information out of that traffic flow. That's the kind of protection you can take care of yourself.

47:46 - Attacking competitor websites

Attacking competitor websites

with Jonathan Bowers, UKFast

Imagine it's Valentine's Day for example, wouldn't be it be good - and very  profitable - if you were the only company selling red roses? Technically you can be... This sort of activity is called a DDoS, or denial of service, attack.

profitable - if you were the only company selling red roses? Technically you can be... This sort of activity is called a DDoS, or denial of service, attack.

Jonathan Bowers is the Managing Director of UK web hosting company UKFast, and says although this sounds like something from a thriller, it's a lot more common than we think. He started by explaining what UKFast actually do...

Jonathan - As a web host, we build data centres that house the computers that power the internet. I suppose, in effect, we connect those computers with the world. So, from that platform, we're connecting businesses with their customers, we're connecting soldiers with their families, paramedics with their training. So, it's a very crucial and important job that the web host does to make sure that these organisations reach the rest of the world.

Chris - What is one of these denial-of-service attacks and what does it comprise?

Jonathan - Well effectively, denial-of-service attack is a huge amount of resource hitting one website. So, if you imagine that you have an advert during Coronation Street for instance and you have a million who decide, "I like the look of that. I'm going to go online and I'm going to try and buy it." Now, you might have a million people hitting that website at one moment. Now, there are very few websites that could cope with that amount of traffic and effectively what a DDOS attack is, is a simulated version of that where nefariously, somebody is attacking a website with so much information that they know the resource wouldn't be able to cope and it will knock that website over.

Chris - When this happens, how much does it cost the industry?

Jonathan - Well, I think probably it's very difficult to say overall how much it costs the industry because I'd imagine, there are lots of businesses who don't like to ever admit to having been impacted by a DDOS attack. But there are a number of stats on how much it costs the industry and it depends how big the business is and it depends exactly what they're doing online. So, if you've got a very busy e-commerce website - let's imagine a retail website that might be expecting 80,000 visitors across their busiest day, imagine if that website was down for the whole of that day because its infrastructure have been taken offline. That would mean it loses out on all that opportunity and all that money. So, you could be talking hundreds of thousands of pounds. For large businesses, the average breach could be worth somewhere between 450,000 and 850,000 pounds to that business.

Chris - Now, UKFast as a web hosting company hosts thousands of business's websites in your data centres. So, have you got evidence that this is actually happening? Can you see evidence that people are taking down their competitors in this way?

Jonathan - What we see tends to be circumstantial evidence. When somebody performs a DDOS attack, they're actually using IP addresses that are very difficult to trace back to any particular place.

Chris - These are like postcodes for where your computer is on the internet, isn't that?

Jonathan - Absolutely. so, every website has a numerical address as well and that's its IP address. What DDOS attacks do is flood with lots and lots of traffic that IP address, that postcode as it were. It's very difficult to trace that back because there's a black market on the internet where people can buy DDOS attacks. Effectively, what happens is, you tend to find that if somebody is attacking a website at a particular time, it's because they have motive. And you can also find that there are other ways that that person might have had a look at that website and effectively try to hack into that website through other vulnerabilities. So, business like ours are being asked to look more and more into whether there are what you'd call vulnerabilities in the website itself that are allowing these things to happen. In reverse, engineering those vulnerabilities, you're often able to see that somebody has actually been in, had a look, disappeared again and in these cases, often, they're not as clever as the DDOS attack itself and it can trace it back. If you can pass that information onto law enforcements, often they're able to then look further into it and discover that actually the DDOS attack came from the same perpetrator.

Chris - And where in the world are these attacks originating?

Jonathan - Well, the attacks originating in a number of key areas and the Asia Pacific area quite often. In fact, in Q1, the first quarter that is of this year 2014, over 40% of all DDOS attacks where originating from China. That numbers has dropped significantly in the second part of the year and in actual fact, the USA is the place with 20% of all originated DDOS attacks. However, it's a bit of a misnomer to believe that just because the DDOS attack originated there, it means the perpetrator who actually paid for it to happen originated there as well because they could be anywhere in the world and they could have bought that from that particular country.

Chris - So, looking at how it would work, if I wanted to push my business online and nobble my competition, traditionally, I would have a marketing budget and I'd spend some money printing some leaflets and posters and a radio or TV campaign or something. What I could do now is to spend some money paying someone nefariously overseas to basically cripple my competitor's websites with one of these DDOS attacks.

Jonathan - Yes, DDOS attacks direct at one particular website. So, you might end up spending quite a bit of money if you were to try and knockout everybody else that sells roses on Valentine's day for instance. But I suppose, the big opportunity for people could be where they rank very highly in Google, but their main competitor ranks perhaps just above them or just below them on that search engine. In actual fact, if somebody is searching at that time then a DDOS attack is hitting the number one term in that search list, then people move to the number two term. If that's your competitor then they might get lucky.

Chris - What can we do to defend ourselves? What can companies like you do to protect the people whose websites you host?

Jonathan - Well, I suppose the first thing is intrusion detection and intrusion prevention. It's important to point out that every website are just like at home where you'd have an antivirus on your computer. Your website should be protected in your hosting by firewalls and by routers and switches that have the ability to spot traffic that is slightly out of the norm for instance across the network. If you can find that traffic that doesn't seem quite right, perhaps sending millions and millions of visitors at one time then often that means that it's out of character for the website and these intrusion detection prevention systems are able to step in and actually, reroute that or alert somebody to it so that they can actually stop this from happening.

54:58 - What makes a good password?

What makes a good password?

Amelia - With the amount of personal information people put online, keeping our data protected is clearly important. But some of the most common passwords used by people include: 'letmein', '12345', and the very original 'password' which surely, are not very secure. So, what is the best way to insure our security online whether it's for our Facebook or Twitter account or something more important that is internet banking. We went to Lorrie Faith Cranor, a security researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, Pennsylvania about her suggestions for a super safe password.

Lorrie - A good password is one that is difficult for other people to guess but easy for you to remember. It should be tough both for people you know as well as from malicious attackers who might make billions of guesses to figure out your password.

Amelia - So, we have to consider attacks from people who know us, as well as malicious hack attempts which can spew out billions of guesses. So, what kind of password simply can't hack it?

Lorrie - To create a good password, pick a word or phrase that you can remember but don't use the lyrics from songs or anything else that's popular and don't use the name of your pet, your phone number, or other information people might know about you.

Amelia - I better start changing my passwords then. So, what's an example of a really tough password to crack?

Lorrie - You might use the first letter of each word in a phrase that you make up then add some extra symbols and numbers or capital letters in the middle. Don't just put them at the beginning or end and don't substitute numbers that look like letters. It's good to have at least 12 characters in total.

Amelia - Wow! That's a lot to remember. So, can we save time by making one super password and then use it for every account?

Lorrie - You should use different passwords for every account. So, some people find it useful to have one secure password that they add a few extra letters to each time. This can help you manage a large number of accounts, but isn't a good idea for your most important accounts. It is much better to write your passwords down in a secure place than to use the same password for multiple accounts. Password managers are also a good way to keep track of your password securely so you don't have to remember them all.

Amelia - So, it would seem a combination of numbers, symbols and lowercase and uppercase letters will hopefully guarantee your accounts are for your eyes only. Thanks, Lorrie. Next week, we are trying to solve the answer to this question from Nikki in South Africa, who wanted a couple of tips for her school project.

Nikki - How is self-cleaning glass made? Amelia - Windows that won't need to be cleaned again, computer screens free of dirt and grime, and no more grubby fingerprints on your smartphone. But how on earth is this possible? What do you think?

- Previous Ant-sized radios

- Next Modifying mice memories

Comments

Add a comment