Halting the progress of multiple sclerosis

In this edition of The Naked Scientists, we’re looking into multiple sclerosis, following the progression of the condition from relapses to neurodegeneration, asking, can we halt the disease in its tracks?

In this episode

00:55 - Life with multiple sclerosis

Life with multiple sclerosis

Lara Kingsman

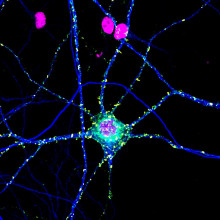

Multiple sclerosis, MS, is an autoimmune condition that causes white blood cells to attack the myelin sheath which protects the outside of nerve cells. This means that the messages which these neurons are trying to communicate across the central nervous system are disrupted, leading to all sorts of symptoms: from numbness and tingling in the body, to difficulty walking, fatigue, vision problems, and cognitive issues.

MS onset often occurs in the young, and it is one of the most common causes of neurological disability in people aged 20-40. There is, sadly, no cure. Lara Kingsman is a teacher from Cambridge with MS…

Lara - I woke up one day about eight years ago now and I couldn't feel a lot of my body from my waist down so I woke up with strange numbness and tingling all the way around my pelvic area, down my legs and it was quite scary to be honest.

James - I can imagine. What happened next?

Lara - So I was quite fit when I first had these symptoms. I used to be a Zimba instructor and I used to do a fair bit of running and I thought I'd just trapped a nerve in my leg and after about a week the numbness and the tingling were just getting really, really, really uncomfortable. It was quite painful and I was not able to sleep at night so I ended up going in through A&E actually and it was on Easter weekend of 2017 but I ended up being admitted for three nights and they gave me a lumbar puncture which is where they tap and see your spinal fluid and they gave me an MRI on my head and my spine and basically it was from that position that they were able to diagnose that it was multiple sclerosis.

James - Obviously some really difficult news and I think one of the difficult things about MS and other conditions like it is that they're not immediately apparent what you might be going through. The symptoms aren't immediately visible.

Lara - And that's the big conundrum really because to all senses and purposes you look absolutely fine. I look fine. I've walked into this room here. I'm able to drive thankfully but it's the unseen that is so debilitating and I think one of the big factors I found in adjusting to having MS it's not the physical symptoms but it's the mental symptoms. So it really plays on your mind. This is a degenerative condition. I'm not going to get better. I'm fortunate enough that I've been diagnosed with relapsing remitting MS which means I will have relapses and then hopefully stabilise. But I don't know if those relapses are going to happen tomorrow or in 10-15 years time.

James - Talk to me a bit about the difficulties of that and I'm going to pick up on the fact you said you don't really know when or with what force it's going to come back.

Lara - It is really tricky and I think I've learned to live a day at a time and psychologically I think that's the only way you can do it. I've had to pull right back on my work as I've said because I just can't guarantee that I'll be there. Basically if friends invite me to things I say I'm reliably unreliable. I might wake up one day and just find I'm just too fatigued. I can't do it or the tingling is just really getting on my nerves and I need to take a nerve painkiller through the day and just try and sleep it through. So there is this frustration that you can't do what you want to do but also that you are just unreliable and when you've been used to holding down a job but also you want to be there for friends and family you have to almost grieve the person that you were and so your life can become potentially quite small. It can strip you of your identity quite quickly and that means you're vulnerable to depression.

James - How have you tried to manage those potential psychological implications?

Lara - My GP was very good. I make no qualms. I'm on Zitalopram which is an antidepressant and it really helps but most of all I think friends and family have been really supportive and also the MS nurses as well as the neurologists and your consultants which you see and also you're just really grateful for the research that goes on especially in Addenbrooke's where I'm attached to and the dedication of scientists who have poured their life into trying to a find a cure for it but also trying to help people manage their condition through disease modifying treatments.

James - It's really inspiring to hear what a positive spin you're able to put on your diagnosis and the good that you can see that's being done to help those with it. I want to touch briefly on treatments because that's what we'll come back to later on in the programme. You mentioned things to manage the psychological aspects of the condition in terms of anything else on the physical side.

Lara - So I'm on a disease modifying drug called Tecfidera which basically helps stop the myelin sheaths around your nerve endings breaking down and I've been on it for nearly six years now and I'm so so grateful to be on it because you feel like you're a sitting duck sometimes without treatments. Some people decide not to go on to treatments and that's fine. All treatments have side effects and you have to learn to live with those but mine's just a tablet I take twice a day and I've gotten really well with that. I also take pregabalin which is a nerve painkiller and I take it at night.

I'd rather not be on it, it has side effects. So those are yeah the drugs that I'm on.

James - Thank you so much for speaking to me being so open. It's really inspiring to hear you speak about what must have been a really difficult time.

Lara - Thank you it's a pleasure to come and chat to you thank you James.

Why does MS affect everyone differently?

Will Brown, University of Cambridge

Everyone experiences MS differently, for reasons which are hard to pin down. Why is it that the lower half of some people’s bodies are affected, for example, rather than the blurry vision experienced by others? Why would the immune system target different parts of different people’s brains?

What’s more, while some people see a resolution of their symptoms after just one flare up, more often, people develop an accumulation of disability after many relapses in what is known as progressive MS.

The mechanisms which underpin these differing pathologies are the subject of extensive investigation, but to help us understand what we do know is happening in the body to bring on the difficult and varied symptoms experienced by those with MS, I’ve been speaking to Will Brown, a consultant neurologist at Cambridge University Hospitals who specialises in Multiple Sclerosis…

Will - So multiple sclerosis is the most common cause of disability in the young and in the UK there's more than 150,000 people with MS and for reasons we don't fully understand females are affected three times more commonly than males. At its heart MS is an autoimmune disease and what that means is that the immune system is misbehaving, it's attacking normal body tissues and in this case those are tissues in the brain the spinal cord and the nerve that goes from the brain to the eye called the optic nerve.

James - And particularly it's impacting the myelin sheath.

Will - Yeah and this is really interesting so we think that there's kind of two broad categories of things that can predispose to MS. So one of those is genes and the second one is environmental factors and we can come on to this but there's been recent work showing that one of the biggest environmental triggers is Epstein-Barr virus and actually this looks almost identical to one of the proteins that sits on myelin and so increasingly we're confident that this is an autoimmune disease. The immune system is making a mistake, it's trying to attack myelin thinking that it's Epstein-Barr virus and it's our job to try and get that back in check.

James - Now Epstein-Barr virus is something that the majority of the population will get infected with over the course of their life. This is the virus that can cause glandular fever I think I'm right in saying. So what is it that causes the people who go on to develop MS to experience the condition that they do?

Will - You're exactly right so over our lifetimes more than 90 percent of us will be infected with Epstein-Barr virus. By the age of 10 that's more than half of us and what we don't understand is why some people go on and develop MS. It seems that some of that risk is due to genetic factors but again those are not completely understood.

James - I'm really interested to go into a bit more detail and zoom in a bit more on the immune response and what's actually happening in a neuron-to-neuron context so talk me through the immune cells involved and how they come to be interacting in the brain in the first place.

Will - So in health we know that there are naughty immune cells and autoreactive cells and they are normally cleared up in the thymus. Some of them will escape into the periphery but they again will be mopped up but people with MS these mechanisms they seem to fail in particular there seems to be reduced levels of t-regulatory cells and there's also some of the effector cells t-cells and b-cells seem to be less responsive to these mechanisms and this means that these cells can then trigger t-cells and b-cells to cross the blood-brain barrier enter the brain spinal cord and optic nerves and then lead to the attacks that we see that cause relapses.

James - When these naughty t-cells as you describe them cross the blood-brain barrier, what's the focus of the disease, what's the damage done?

Will - This autoimmunity this wave of inflammation as the inflammation happens it leaks out from the blood vessels into the surrounding brain and we can see that on a brain scan we can see these new areas which we call lesions in the deep tissue called the white matter and as the inflammation leaks out it causes the insulation that surrounds the nerves to come off and hence we call it a demyelinating condition because that protein is called myelin. And that means the nerves don't function so well and as a result people experience symptoms that may be weakness or numbness imbalance problems and problems with their eyes for example but over time the inflammation will improve and the myelin will go back on the body can repair itself and that leads to an improvement in symptoms and so after that episode which we term a relapse there's a period of relative stability and during that time there'll be no new symptoms until the next wave happens.

James - Is treating MS just a case of treating the inflammation and the flare-ups as they occur and relapsing remitting manifestations of the disease?

Will - So sadly not. Increasingly we're realising that inflammation is the biggest component at the beginning of the disease but we're also realising that other processes are happening right from the beginning. These are processes that lead to nerve death and these ultimately lead to the most disability.

James - For relapses, symptomatic periods of the disease, how effective are the treatments?

Will - So I'm a little biased but I'd argue that multiple sclerosis is one of the most exciting areas for therapeutics and that's because it's one of the few areas of neurology where we have truly disease modifying treatments. So since the late 90s more than 20 treatments have been licensed which can effectively reduce relapses and the disability that comes with them. I classify these into low, moderate and high efficacy all on the basis of the impact on relapses. So low efficacy treatments , which were the earliest ones that came about, reduce relapses by about a third and similarly they have a reduction in disability that comes with each relapse. More recently tablets have been licensed. These reduce relapses by about half. And finally the high efficacy treatments reduce relapses by about 80 to 85 percent and with a correspondingly greater effect on disability. But it's not that simple. With increasing efficacy usually comes increasing risk and also the monitoring requirements. So the decision is not simply a case of what's the strongest treatment we can give someone but it has to be a joint decision made with the patient to figure out what is the right treatment for them, what treatment do they need in terms of efficacy but also choosing based on their safety profiles, their family plans and also monitoring.

How can we treat progressive MS?

Nick Cunniffe, University of Cambridge

In recent years, disease modifying medications for relapsing MS have come on leaps and bounds. They work by dampening down the immune system in a number of ways: they might target the specific immune cells involved in attacking myelin, or stronger drugs might suppress immune cells more broadly. This might be more effective, but the trade off could be that weakening the immune system more broadly could leave a patient susceptible to other dangerous infections.

But, while these treatments are effective at reducing inflammation during a relapse, they have little impact on disability that builds up over the course of many years and lead to nerve death and neurodegeneration, leaving a big unmet need for reducing disability progression. To learn more about progressive forms of MS, and how we can treat them, Nick Cunniffe, clinical lecturer in neurology at the University of Cambridge, explains more…

Nick - Ultimately, we need to consider the nerve structure. Many people will be familiar with the fact that there's a neuron, and that has a long process called an axon, which is the main wire that the nerve fibre is going to send signals along. And then surrounding that is a lipid protein structure called myelin that's made by a cell called an oligodendrocyte. And that essentially is an insulating and protective structure around the axon. Now, when we think about progressive MS, the pathology is slightly different to the relapsing remitting MS. So the inflammation, the damage to both the myelin and the axons is much more compartmentalised. So rather than the immune system systemically becoming dysregulated with those immune cells getting from blood into the brain and damaging nerves, actually in progressive MS, the inflammation is proceeding unchecked, often termed as smouldering away within lesions, behind a closed blood-brain barrier. And that's important when we think about treatments for progressive MS, because many of our treatments won't get at that process.

James - And therein is the problem, of course. But do the disease-modifying drugs we use to treat relapsing MS have any effect on progressive forms of the disease, or are they completely ineffective?

Nick - We now know that it is absolutely in someone's interest to treat them with high-efficacy drugs early to prevent progressive MS, so we can sequence our drugs better, not just to prevent the relapses, to prevent progression. But as I mentioned before, the inflammation gets different as you get older, as you've been living with MS for longer. So how can we target that compartmentalised inflammation? A couple of papers were presented, a couple of trial results were presented, on the same compound called tolibrutinib. So this is something called a BTK inhibitor. And what this drug does, it's a small molecule, so it easily gets into the brain, and it has a role at suppressing the abnormal activity of B cells that have become activated, but really importantly, it also modulates the activity of microglia. So these are the innate cells that are contributing to that smouldering inflammation that's underlying progressive MS. And what they showed was that in people with non-relapsing secondary progressive MS, so a category of people in which there's no current treatment for, that this drug could reduce the rate of disability accumulation.

James - So those drugs will have a role to play in reducing that smouldering, behind-the-scenes inflammatory process. But are there other pathologies we need to be worried about when thinking about progressive MS?

Nick - Absolutely. So there is a natural inbuilt process called endogenous remyelination. So if you or I had a demyelinating insult in our brain, a group of stem cells, we call them oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, OPCs. And when we have demyelination, those cells will become activated, they will migrate to the area of damage, differentiate, so make more of themselves, and then they will start laying down myelin. That's what should happen, but it becomes less effective as we get older, but it becomes particularly deranged in multiple sclerosis as well. So we think the failure of remyelination or the failure of repair is one of the mechanisms by which more advanced disability develops, usually in people in their 40s and 50s who've been living with MS for a longer time.

James - So what can we do about it?

Nick - So we think that one of the main blocks to repair is differentiation of the OPC. So various different lines of research has been undertaken to try and understand the reasons why this process fails so that we can identify druggable targets to kick it into action. So several drugs that have either been novel or repurposed have been taken to trial to see if they can enhance this process and stick myelin back on nerves. And across several trials now, we've seen positive and encouraging effects.

James - That is obviously brilliant to hear, but I want to also, while I've got you, ask you about another promising line of research going on to help halt the advance of progressive MS. Could you give us an introduction, please, to neuroprotection?

Nick - If we're not considering remyelination, the other thing you could conceivably do is try and enhance the resilience of the underlying axon, the underlying nerve fibre. So we call that neuroprotection. Now, what we're doing here is lumping together many different mechanisms because there are lots of different reasons why an underlying axon will be vulnerable to degeneration in the long term. And all of these factors contribute towards that nerve fibre withering, dying, and that is ultimately going to lead to progressive disability. So ultimately, when we talk about neuroprotective strategies, we are talking about a factor that addresses one of those different mechanisms.

20:54 - Can we speed up MS clinical trials?

Can we speed up MS clinical trials?

Emma Gray, MS Society

Neuroprotection for MS stops axons, the backbone of neurons, from degenerating as a result of demyelination. There are a number of intricate processes which cause this to happen, and so potentially a lot of different methods of stopping it.

But clinical trials are huge beasts. You need thousands of participants to make them hold any scientific weight and, due to the slow nature of MS progression, you need very long time periods over which to study them. Clinical trials are set up in this way for a reason. Each phase helps determine whether a treatment is safe and ready to progress to a broader trial. So how might we make this process quicker and more efficient, and speed up the process of finding neuroprotective treatments for progressive MS? Emma Gray is head of Clinical Trials at the MS Society, who have funded a huge project to do just that…

Emma - We have to have randomised controlled trials. They're the gold standard in terms of, you know, a patient having confidence that a treatment is safe and effective for the regulators to be able to allow it to be prescribed. So we can't get away from that, but we need to be smart about it. We know that all the trial stages are all required, but they're all done separately. You know, you set them up, you shut them down. You might have to apply for funding for the next stage. You set that up, you shut that down. Surely there must be a better way of doing that. Also, normally in traditional trials, you would trial your potential treatment of interest compared with a placebo or a dummy treatment, or if available, a current existing treatment. So again, that's a really inefficient way of just testing one placebo against one drug.

James - As I understand it, you've been looking at inspiration from other fields of medicine, where there are other methodologies of conducting clinical trials in operation.

Emma - Yeah, we have. And we're hugely inspired by the oncology field, especially prostate cancer, a trial called STAMPEDE. So we thought, we have to be able to do this. So we got some of the statisticians from that trial and said, look, can you come and help us? And so, yeah, so we got the community together and started to design a really exciting, what we call multi-arm, multi-stage trial called Octopus, where you can test lots of treatments at once, but also you merge the stages. So you have one consecutive trial that enables you to, as soon as you find a new treatment, if you're able to, you could add that in. If you find out one of the treatments aren't working, you could remove that. You could change the outcome measures that you're testing within the trial. You can change the cohorts. If you're able to personalise your trial in a certain way for a certain group, you could do that. And you're also, with these trials, able to link it to other data sets to bring new knowledge back in to develop new treatments in the future.

James - You started by talking about the kind of multi-arm phase of the trial, using multiple drugs at once. How is that made possible given the rigours of clinical trials usually and the safety with which they have to be conducted?

Emma - Yeah, it's a really good question. I mean, the short answer is you need very clever statisticians. So what you do, you'd have one placebo group or dummy drug, whatever you want to call it, control arm, against, instead of just having one, you can add in say two or three arms with active treatment in them. So Octopus has started actually with what we're calling repurposed off-patent drugs. So these drugs are used for other things, but we know that they are cheap and could be readily available for the population. So what you need to do is to consider all the possible biological mechanisms that trigger accumulation of disability in people with MS, and then look for drugs that potentially target those mechanisms.

So we did a huge piece of work looking at hundreds of potential drugs, whittling them down, shortlisting them, reviewing them, getting them reviewed by experts, coming up with a shortlist. So we're starting Octopus with two drugs. One is metformin, which is a commonly used drug for diabetes, and alpha-lipoic acid, which is actually kind of more of a food supplement, if anything else. We've got evidence that they are worth testing in MS. We also have other drugs, on a shortlist or a watchlist for the future, as and when the trial would be able to add the new drugs. You need to have the finances in place. You need to have the statistics in place. There's lots of things to do before you can add new drugs in, but there's plenty of things we'd like to test when we get there. I mean, obviously, the development of novel treatments is really, really important, but certainly for a sort of charity academic enterprise, using these drugs, I mean, they're great because you don't have to do the early safety testing of them. So they can go into later stage trial knowing they're safe and effective in people. I mean, we might not know everything about their safety profile in someone with MS, but the trial will do that in a really controlled, safe way.

James - Because you've got multiple drugs working at once and you're analysing on the fly, could you then look to further streamline the process by directing more energy towards treatments that seem to be working and away from those that seem not to be so effective?

Emma - Absolutely. So what we do with these studies is that normally, with a clinical trial, you'd have an outcome measure or a measurement you're looking for at the end of the trial to tell you whether or not that drug is effective. And what we do in these sort of MAMs or these efficient designs is use what we call interim outcomes. You find that you put in a measurement that is telling you something about your ultimate goal. So for MS, we're looking at people, how far they can walk in combination with other measurements like upper limb function. So what we do is we look for an interim outcome that tells us that if we get some signal there, it's worth continuing, doing an MRI scan essentially, halfway through the trial to see if the drug is worth continuing with or not. If it's not, it gets dropped, which frees up the resources to add in a future arm. Or if it is working, then what we do is we then randomise more participants into that arm. So we're able to kind of make that group bigger to give us a clear answer whether that drug is safe and effective or not.

James - So that's it in principle. In practice, how many people have you been able to recruit in the Octopus trial? And how's it been going?

Emma - So we've currently got around 400 people with MS recruited into Octopus. We're going to get to about summer, kind of autumn 2026 to analyse our interim outcome, that MRI scan, to find out if the two drugs are worth continuing with. Then the ones that are, we will then add more participants in, including more participants in the placebo control arm. And then I think we should get to 28, 29 before we have a definitive answer. But in the meantime, we're going to be working on adding in new arms as well. So it becomes this complicated, staggered design. But the idea is that every few years you read out something about the trial, whether it's this drug is worth continuing with, or, you know, we potentially have a new treatment for MS.

Comments

Add a comment