Hands-on, Minds Open: The Changing Face of Science

This week we're asking whether scientists and technologists are in short supply, and how the way that we teach science in schools is changing: some classrooms are pumping out published papers! Plus, in the news, a 2 metre-long scorpion, seabirds with stomachs stuffed with plastic, and the facts behind fat - is butter really all that bad for you?

In this episode

00:54 - Butterfly inspires new nanotechnology

Butterfly inspires new nanotechnology

with Dr Tim Starkey, University of Exeter

If you're lucky enough to visit the tropical forests of central America, you might  spot the highly distinctive bright blue wings of a Morpho butterfly. And if you look really carefully, you might see their wings subtly switching colour in response to changes in the chemical make-up of the surrounding air. Now, taking his inspiration from these insects, Tim Starkey, from the University of Exeter, has developed a new form of sensor technology that works the same way, as he explained to Kat Arney...

spot the highly distinctive bright blue wings of a Morpho butterfly. And if you look really carefully, you might see their wings subtly switching colour in response to changes in the chemical make-up of the surrounding air. Now, taking his inspiration from these insects, Tim Starkey, from the University of Exeter, has developed a new form of sensor technology that works the same way, as he explained to Kat Arney...

Tim - Ususally colour is produced in two ways. The most common one is through chemicals. So for example most of your clothes and the things you see around you are created through pigmentation. And that's where light comes in. Some of it is absorbed and what is reflected or transmitted to your eye, you perceive as the colour. These butterflies create colour through structure so they're made up of lots of very thin layers which manipulate light to give you a blue colour.

Kat - What does the structure of these wings look like? How do they look?

Tim - If you were to take one of these butterflies and take a scale off, if you take a cross section and look at these sort of side on, you'll see that this scale contains what look like tiny little Christmas trees which are about a millionth of a meter tall. So, it's like a hundredth of the thickness of a human hair. Within these little structures are reflecting layers. So, it's made up of material which is a protein, much like our fingernails. But it's layered in such a way and its structure exists in such a way that light will come in and the butterfly is optimised to reflect blue colour.

Kat - So, how did these little Christmas trees, these structures change when different gases or different levels of humidity are around?

Tim - What happens is, because of the local chemistry, the vapour in the atmosphere will stick to the Christmas tree in different places. So, for one chemical for example water, it will stick to the top of the Christmas tree preferentially and for a different chemical, maybe methanol or ethanol, or some other nasty thing in our environment would stick in a different way. The actual positioning or the way that these vapours stick to the nanostructure gives rise to these different optical or different colours.

Kat - There are devices being developed that can sense nasty chemicals, different levels of gases in the air, how could you use this observation that the butterfly's wings do change colour in response to these chemicals? I'm assuming that you can't make a sensor just of a butterfly pegged in the middle of it.

Tim - No. So, when the initial study came out, when we realised when we were studying the butterfly, we had some proposals that maybe we should farm these butterflies and turn them into sensors. But we're so very much against that idea because we know we can go one better and make an improvement on nature's design. So, we actually create these nanostructures through special fabrication processes. It's very much like taking a photographic film and exposing it to light to create colour, but we actually do that with electrons to create these very intricate nanostructures.

Kat - What sort of chemicals could they detect? Could they pretty much detect anything you wanted to pick up?

Tim - I think we could actually tune these for different chemical, biological sensing applications. Really, this study shows the principles by which we can do that. Providing we have the correct chemistry and we can create these structures, we can even grow them potentially in the future then you could tune them to many different applications.

Kat - How soon do you think that might be that you could see a working prototype sensor based on these butterfly wings?

Tim - Often, scientists are sort of limited by the scale that you can produce these, so it's fine to produce them in the lab and they work perfectly. But really, it's about making them cost effective and being able to roll them out for mass market. It's a difficult question to answer, but assuming that the techniques by which we can create these continue to improve at the rate they have been recently. Conceivably, things like this could be put into market, possibly in the next few years.

05:06 - 90% of seabirds are dining on plastic

90% of seabirds are dining on plastic

with Dr Eric van Sebille, Imperial College London

Plastic is everywhere, from our homes to our cars to our food, but where does it  all end up once we're done with it? The sad fact is, much of it ends up in our oceans. And with all this plastic floating around, some is inevitably picked up by sea birds. Eric van Sebille, from London's Imperial College, has looked at 60 years worth of data and found that, compared with the 1960s when only 5% of birds were found to have plastic items lodged in their stomachs, today that figure has risen to 90%, and could reach 99% in 2050. Connie Orbach spoke to Eric about the problem....

all end up once we're done with it? The sad fact is, much of it ends up in our oceans. And with all this plastic floating around, some is inevitably picked up by sea birds. Eric van Sebille, from London's Imperial College, has looked at 60 years worth of data and found that, compared with the 1960s when only 5% of birds were found to have plastic items lodged in their stomachs, today that figure has risen to 90%, and could reach 99% in 2050. Connie Orbach spoke to Eric about the problem....

Erik - We think that these birds, they're foragers, right? They spend a lot of time just hovering above the ocean surface, trying to look for fish. And maybe sometimes, they mistake a lighter for a fish or maybe they're just curios and they want to pick it up.

Connie - And so, why do you think there's so much plastic in their stomach? Where is it all coming from?

Erik - Many people will have heard about what we call the garbage patches - these areas in the open ocean where all the plastic in the ocean at some point accumulates. But what we found is actually that there's not very many seabirds foraging there, not very many seabirds eating the plastic out of the ocean. So, most of the harm due to the plastic is actually done in other regions closer to our coastlines.

Connie - What does it mean that these birds have plastic in their stomach?

Erik - We don't really know what the plastic does to the seabirds, but we're pretty sure that it is harmful. It can be either from gut blockage or actually, wounding them internally. The other thing that can happen is that it's actually quite a lot of plastics in some cases. In some cases, we found up to 8 % of body mass in the stomachs of seabirds. For a grown person, that would be 6 kilos. So, that's like walking around with two big cats everywhere you go. And then thirdly, it might be that there's actually toxins in the plastics itself and these toxins might leach out in the birds.

Connie - The idea of carrying two cats around does sound really annoying. When I think of seabirds - I think of seagulls which in the UK are kind of pests. They steal everyone's chips by the seaside - why should I care about what's happening to these seagulls?

Erik - So first of all, although seagulls don't really have a good name, many of the other birds are beautiful. Think about penguins, think about albatrosses. But I think more importantly, the seabirds are almost literally the canary in a coal mine here. If seabirds pick up plastics, we can be pretty certain that other creatures also pick up plastics. It's just that seabirds have always been easy to study. They nest on land so the literature on seabirds goes back much, much longer than many other animals.

Connie - Is there a possibility that the seabirds could be picking up some of this plastic through the animals that they're eating as supposed to just directly?

Erik - Probably, that's true but from our studies, it was really hard to entangle that. So again, that's something that we really need to understand. We roughly know how much plastic gets into the ocean. We don't know where that plastic is, and where worryingly, some of it might get into animals, in what we call the biota. So, the plastic might actually reside within birds, within fish, within plankton, within mussels. All of these creatures might actually take up plastic.

Connie - I mean, some of the things you mentioned then - mussels and fish, they're the things that we eat as well - is there a possibility that we're also taking in plastics through the food chain?

Erik - Yes, although nobody really knows how big this is, how much plastic we really are taking in through the food chain. I think we have to realise that we live in a plastic world. Plastic is a fantastic material, right? It is durable, it is lightweight, it is waterproof. It is everything you want from a material that's so versatile. The problem is just how we manage the waste of plastic. We need to make sure that it doesn't get into the ocean, that it doesn't reach natural environments.

Connie - So, you're saying that it's not that we should be using less plastic. It's that we should be managing it better.

Erik - I think we should be more aware that if we use plastic, we should take care of how that plastic is discarded in the end.

Connie - Then this figure, this 99% of seabirds in 2050, do you think we can turn this around?

Erik - Yes. One study reported that after there was a big effort in the European Union to reduce the amount of plastic getting into the ocean, actually, there was a significant drop in the amount of plastic in seabirds in the North Sea. So, that's a great news story. It means that if you stop, the birds will get less harm, they will rebound.

09:56 - Fat: the good, the bad and the ugly

Fat: the good, the bad and the ugly

with Professor Peter Weissberg, British Heart Foundation

It can feel like we're constantly bombarded with claims and counter-claims about the harms of cholesterol and fat. Now, according to recent headlines, there's controversy over whether traditionally 'bad' saturated fats, like butter, really are 'bad' for our hearts. So how do we know what to believe? And what should we eat to keep our hearts healthy? To get to the 'heart' of the issue, Kat Arney spoke to Peter Weissberg, medical director at the British Heart Foundation...

Peter - When it comes to these sorts of study, you can't rely on any one study. So, headlines based on a new study that says a particular dietary constituent is either good or bad for you is probably not worth taking a lot of notice of. What really matters is the cumulative evidence of many, many studies over many, many years. This is true of all forms – medicine and also all forms of research. You should never really take the word of one particular study. And in those circumstances, when you look at the totality of the evidence that’s available, and the weight of the evidence that’s available, that evidence suggests that a diet that’s very high in saturated fats is probably bad for your heart. A diet which is low in saturated fats but higher in polyunsaturated fats is probably good for your heart. The problem with that is that it’s much harder to do carefully controlled, randomised control trials of different dietary approaches to determine which is the best way to achieve firstly the lowering of the bad cholesterol, but secondly, ensuring that the rest of the diet is sufficiently good for you, that you're not substituting something good. In other words, taking out the saturated fat from your diet with something which may be very harmful, putting loads and loads of calories for instance which will put you at risk for other reasons. So, I think the focus perhaps over the last few years on particular nutrients whether it be saturated fat or whether it be salt or whether it be sugar is not that helpful. What we really need is a reasonably balanced diet.

Kat - We’ve seen some headlines recently saying things like, “Margarine will kill you but butter is absolutely fine.” In terms of the argument about good fats, bad fats, trans fats, unsaturated fats, is there something that we can take away and think about from this?

Peter - Well, I think with the trans fats, where they're concerned, I think the evidence is pretty strong. They're not good for you. Actually in the UK, most of the trans fats have been taken out of the margarines and the softer spreads. So, from our perspective in the UK, it’s not really a big issue any longer. Whether you eat butter or whether you eat the lower cholesterol spreads, I think it’s entirely up to you. The important message is that if you do eat butter, don’t eat loads of it. If everything you eat is layered with butter and if you cook in butter all the time that you're taking in a very large amount of butter then that may be bad for you. And that really applies to all the other nutrients. If you overdo it, you're probably not going to do yourself any favours. If you cut it out completely, you're probably going to do yourself no favours. When it comes to dietary constituents, we’re never going to have categorical (Carl Stein) black and white evidence. It’s always going to be a balance of best evidence available and that’s liable to change. There is only one (Carl Stein) certainty about diet and health and that is, if you don’t eat, you die. So, you have to eat something.

13:46 - Robotic hand picks up UK Dyson Award

Robotic hand picks up UK Dyson Award

with Peter Cowley, Tech Investor

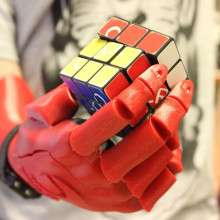

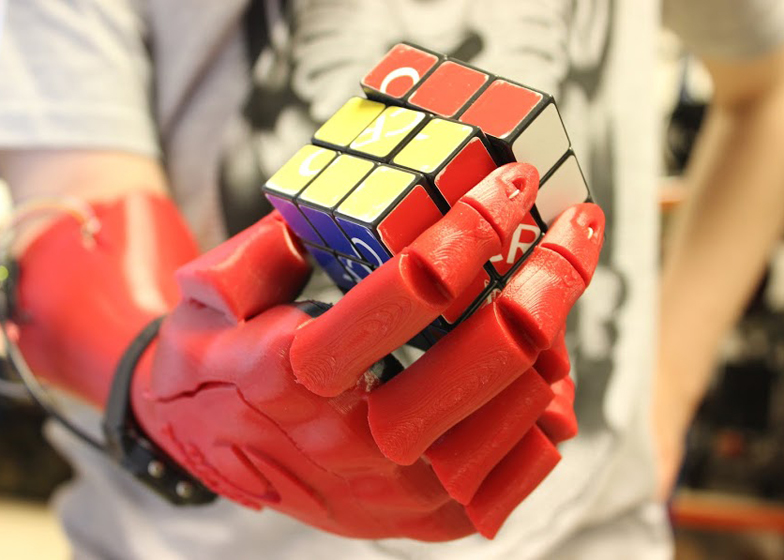

Last week Joel Gibbard won the UK leg of the James Dyson Award for his 3D  printed prosthetic arm. Joel will now go on to represent the UK in the international Dyson Awards. Winning any type of award is always good but why are we excited about this one? Peter Cowley, tech investor, told Graihagh Jackson a bit more about the awards...

printed prosthetic arm. Joel will now go on to represent the UK in the international Dyson Awards. Winning any type of award is always good but why are we excited about this one? Peter Cowley, tech investor, told Graihagh Jackson a bit more about the awards...

Peter - Well, many people will have heard of Dyson and the various forms of domestic plants he's produced. About 8 or 9 years ago, he set up a charity specifically to entice engineering students, probably his own students from 18 countries around the world to enter into this award which is really just to find the best product that would solve a problem.

Graihagh - Okay, I see and tell us a little bit more about this year's winner. What is this prosthetic hand?

Peter - This hasn't yet won the international award. It might do of course.

Graihagh - So, this has just won the UK leg to get into the finals.

Peter - The final ones were announced just before Christmas. This is in fact a bionic hand and the idea behind is it's 3D printed so it looks like a hand. If you went and looked online, you can see they're doing versions which is purely plastic and then ones that are covered which look the right sort of colour for a hand. But the important thing about it is that it's driven by electrical signals in muscles in the forearm so that with some training and some tuning or tweaking, one will be able to actually operate the fingers and the thumb, and pick items up, just by effectively doing what one would've done before if one still had a hand.

Graihagh - Okay and this is not available already yet in the prosthetics industry?

Peter - I'm not one of the judges on this panel so I can't answer that, but clearly, there are some high profile judges who have chosen this thing. There's various things about it, a.) it's open source which is likely unusual, b.) it's already got some funding from the crowd (some product funding), and c.) it's apparently going to be considerably cheaper than anything else that's out there at the moment.

Graihagh - So, lots of positives there. How much will this win and will that then take it off the ground and into the wider world? What's the scope for it?

Peter - No. This will have won about 5,000 pounds. If it wins the international award, it will win about 30,000 pounds. Those numbers are not big enough clearly to actually generate a product and get it out into the market. So, there are various other ways of doing that.

Graihagh - You mentioned the crowdsourcing.

Peter - The crowd, yes. There were various forms of crowdsourcing. This is a product crowdsourcing but there's also a crowdsourcing of loans which may not be possible for early stage business or crowdsourcing of equity. But there are other ways of getting equity into a business. So, it commonly takes some hundreds of thousands of dollars or pounds or euros just to get to start up a business and this prize won't be anything like enough to do that.

Graihagh - Just giving them a little - perhaps an edge and in terms of previous winners, are there any that we might have heard of?

Peter - One that's probably most successful of all the international awards at the moment, you probably haven't heard of is called Plumis which is a fire suppression system for the home. There are many thousands of homes already fitted with them, but even the people who've got them fitted won't necessarily know the product. It's one of these things like a fire extinguisher.

Graihagh - It's top secret, yeah.

Peter - That's sits in the corner and doesn't do anything until there's a fire. This system works by mist. So, this is a very small mist droplets which float in the air and they get pulled into a flame. So the idea behind it is it would either fit underneath the tapper on the wall, be set off by heat alarm, not by a smoke alarm and then it will put the fire out. At the same time of course, the alarm is going off and one hopefully get out of the building quickly. But if one was disabled or asleep perhaps then this has got a good chance of saving the person or people.

Graihagh - I guess it gives you a bit more time perhaps if you were disabled. It's not easy if you're in a wheelchair to get out of the house as quickly as you might like.

Peter - It's not just time, but it also could put the fire out. I mean, the collateral damage, if you had a fire in the bottom floor of a block of flats, imagine what that could do there. The other thing about sprinklers is, sprinklers distribute an awful lot of water. This mist system distributes and it only uses about 8 times less. So, the actual damage after the fire is put out is much less.

Graihagh - Yeah, because I've actually - sadly, a friend had a fire and actually, one of the most damaging things was the water but also, the smoke as well. The smoke was really damaging.

Peter - Yeah.

Graihagh - Both things are cheaper alternatives to what we already had. Is there anyone who's invented something that just wasn't there before that's completely like new on the market?

Peter - It's a really canny one which I actually met the guy, the inventor a couple of years ago which is to try and stop fish that are too small being picked up in a net. It's hard to imagine on the radio, this, but it's a little device that's a size of a ring which allows little fish to swim through. So, this is actually in the mesh of the fishing net. So every now and then, there'll be a little ring and the important thing about it, this ring is actually illuminated. So underwater, the fish for whatever reason, are then attracted to this illumination and then they will swim, and they'll get into safety because tens of millions of tons of fish wasted because it's either wrong type or they're too small.

Chris - Is that an engagement ring because I was thinking about they might be female fish you see and they might be attracted to a very sparkly...?

Peter - This is remarkably good for somebody who has just got back from Australia. How do you manage to crack a joke, Chris?

Chris - That's why I made it because for me, it's about 4 o'clock in the morning, right?

Graihagh - Thank you so much, Peter. Peter Caley, tech investor.

19:02 - Giant sea scorpion discovered

Giant sea scorpion discovered

with Dr James Lamsdell, Yale University

Now here's a story with a sting in the tail - scientists are claiming to have found the remains of the biggest and the oldest fossilised scorpion. It was more than 1.5 metres tall, but it didn't live on land; it inhabited the deep ocean and lived 460 million years ago. It's a distant relative of the horseshoe crabs that are still around today. Joanna Kerr spoke to Yale scientist James Lamsdell. He had the painstaking task of piecing together the remains of the creature, which were found in a meteor crater that sat on the floor of an ocean in what is now the state of Iowa in the USA...

James:: I tend to work very closely on various arthropod groups and Eurypterids or sea scorpions are sort of the primary group I work on. And so, what we’ve done is found the earliest known representative of this group which means that we know these things were occurring earlier than we previously thought. We also found out that this thing was a large a predator and this means that these things were very important members of these early ecosystems.

Joanna:: When you say ‘a large predator’, what sort of size are we talking about?

James:: So, the biggest ones we’ve found, bear in mind that these are moults so this probably would have got bigger than this – 1.7 metres long.

Joanna:: What does that look like? I mean, when I'm imagining a 1.7-metre long scorpion, I imagine something out of the film, out of like Jurassic Park.

James:: This thing would’ve been obviously a very aggressive animal. The first thing we noticed were this big appendages with these long spines coming off the head. These things sort of have been used to grab prey. The body would’ve been vaguely unusual. I mean, this thing was just a really bizarre animal. It was really strange-looking. We named it Penteconter which is named after the Greek Penteconter which is early warship. The reason we did that is not only is this an early large predator, but the outline from above kind of looks like these Greek warships. It was very sleek and the head is projected into this strange prow-like structure that just looks like the front of the ship. And then there are paddles coming off the back of the head which would’ve helped it swim.

Joanna:: When you found the fossil, was it a whole fossil? Was it something that you had to piece together like a jigsaw? What did you actually discover?

James:: The initial discovery are made by researchers at the Iowa Geological Survey. And so, they found these sheets of black material that was kind of paper-like and you could sort of peel it off the rock. And so, they did this excavation where they dammed the river and dug out 8 metres of this rock and then I got all these material to look through. This stuff is fragmented exoskeleton and it really does look sometimes, like this animal has just moulted. And so, what I have to do then was first of all, get this exoskeleton out of the rock which was easier than it could’ve been because the rock thankfully became very soft when got it wet again, so I could sort of peel this off. But then I essentially had a jigsaw puzzle where somebody had removed some of the pieces and then dumped a bunch of other jigsaw puzzle in with it. And so, I had to sort of workout which belonged to which animal, what went where and just basically, place this meter and a half long animal together from fragments that were no bigger than 10 centimetres each.

Joanna:: That sounds really tricky. This is the first example of this sort of fossil. Why do you think this was so well-preserved so that it allowed you to actually tell what the fossil was?

James:: A lot of it has to do with the environment of where this thing was found. So, these things seem to have (concreated) into this old meteorite crater to shed their skins. The first is the fact that these are shed skins, meant that scavengers will not have been interested in them. So, we wouldn’t have had to deal with animals picking up corpses which is what you would normally have when you're trying to have something fossilised. This environment was very deep, very calm. There was not a lot of wave action. There was also lower levels of oxygen in the environment than usual. And so, this meant that decay probably was really supressed. And so, there was really not much around to break down these fossils. And so, we’re really lucky that this meteorite crater was here for the duration, so that we can get this exceptional preservation. The preservation really is exceptional. I've never seen anything like this before and we can see things like patterns of the hairs on the legs which is fantastic...

23:12 - How is science education changing?

How is science education changing?

with Dr Becky Parker, Institute of Research in Schools

Considerable sums are being ploughed into initiatives to encourage more people into  STEM subjects - that's science, technology, engineering and mathematics. One such initiative is by getting pupils to collect, anaylse and publish data in peer reviewed journals. Graihagh Jackson spoke to Becky Parker about the Institute for Research in Schools but first, she got the perspective of sixteen year old Amy O'Toole, to hear what she thought about science education...

STEM subjects - that's science, technology, engineering and mathematics. One such initiative is by getting pupils to collect, anaylse and publish data in peer reviewed journals. Graihagh Jackson spoke to Becky Parker about the Institute for Research in Schools but first, she got the perspective of sixteen year old Amy O'Toole, to hear what she thought about science education...

Amy - Well to me, science was just a boring subject and I never thought it would play a major role in my life. To be honest, I didn't see the point in having it as a subject, but I think that was mostly down to the fact that I was never taught it as a scheduled lesson until I was in the upper years of primary school.

Graihagh - We'll be hearing more from Amy later in the programme, but first, Becky Parker, director of the Institute for Research in Schools and also a secondary school physics teacher is with us. Is this a common perception amongst youngsters?

Becky - Well, I think it may even be more so. The new GCSE's and A Level's being started right now actually don't have even practical work as part of their assessed grade. Now, we hope that teachers do practical work, but much of syllabuses are very content-heavy and it frightens me to think that what we try and teach them, all the answers are known. There's no sort of scope for the students to contribute, you know, they turn the page and see the results of the experiment they've just done. The sort of aspect of how science works is a bit contrived. I think young people have a love of science, it's just it gets a bit deadened. I think teachers are doing their best. I think we just need to support teachers to let them do real science when they're actually learning science rather than just a set body.

Graihagh - Indeed. I remember very clearly my science lessons. Most of the experiments were actually done by teachers at the front of the class. There wasn't anything hands on and there certainly wasn't anything where we were actually conducting our own scientific investigations of stuff that isn't known about so much. Do you think that's the main reason why perhaps youngsters might think it's a little bit boring or might not be going into the discipline?

Becky - Yeah. I think this sort of like doesn't mean enough to them and it doesn't nurture the potential they have. We just think there's so much content they need to know, but perhaps in the internet age today, perhaps they don't need to know all that content. I mean obviously, they've got to get exams but we've got to be able to sort of inspire them with the wonders of science rather than thinking they've got to get through a certain quantity of material and not do anything investigative and inspirational, experimental themselves.

Graihagh - Because ultimately, this isn't really what science is about. You don't sit around and read a text book the whole time. You're actually out there and investigating things. Science as education has been changing recently and I've noticed there's this increasing pattern where children are actually beginning to do science themselves that's previously been unknown before.

Becky - Yeah. I think there's a number of schemes and what we're trying to do at the Institute for Research in Schools which has just established - thanks to a fantastic philanthropist funding us to start up. We're trying to make schools able to have the support from us to actually take part. We've got a number of national projects already going, we've got one big project called CERN@school where we have detector chips from the Large Hadron Collider in 50 schools across the country, and we've put a detector in space. The students design this and they're getting new data off which is useful for NASA. Students can do amazing things and we've got to give them the ability to take part in this stuff.

Graihagh - What strikes me here is that not only are these students becoming scientists in their own right, but also, this is a great potential for professors to help outsource some of this research to younger people as well. It's like a two-fold benefit so to speak.

Becky - Well, it is exactly and I think if universities start to realise there's this whole group of young people who have the ability to contribute - I mean, it's a bit like Citizen science but a bit more beyond that because you want the students to actually do some of those real investigations of, "what computer programmes do I need, what sort of analysis do I need?" You want them to use the skills of a scientist to contribute to a major research project. They don't have to start doing that at the end of their university degree. Many more schools can do thi and that's what we want to do, to make it a more standard thing that teachers have that inspiration and re-invigoration in their subject. Students see what real science is like and universities have some more meaningful interaction with their partner schools.

Graihagh - Indeed. But one thing that does strike me is, how can you trust this data? How trustworthy is it? Is it following the correct standards that you would expect of a peer reviewed publication?

Becky - Yes! We have to go through exact... that's why we publish my student's work in peer reviewed journals. We have say, data from the satellite. I've got an expert in astronaut dosimetry flying over from NASA next week to talk to my students about their data. This is proper stuff. It's not anything Mickey Mouse. It's the real thing and that's what we should give our students an experience of. They don't have to just be given sort of cleaned up perfect things. They should see the real world of science.

Graihagh - What sort of reaction have you had from your students very briefly?

Becky - Well, they love it! I mean, it's the chance for them to actually feel as though they're making a contribution. I think that's one of the real downsides of science education is, they don't feel they can ever contribute. Yet, they've got amazing ideas and they're so skilled in so many areas. And so, they can actually see how they might see themselves in the future as a contributing scientist and so many of them carry on and be real, proper scientists of the future.

29:29 - Pi in the sky thinking

Pi in the sky thinking

with Carrie Anne Philbin and James Robinson, Raspberry Pi Foundation

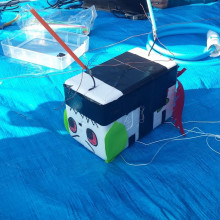

A project that allows students of all ages to collect and analtse data is called the Skycademy. It involves attaching a mini computer to a hellium balloon and sending it on to the borders of space. The balloon pops and the mini-computer - a raspberry pi - returns to Earth on a parachute. The students retrieve it and analyse the data they coded it to collect. Connie Orbach took part in a trial run of the project with the Raspberry Pi Foundation's Carrie Anne Philbin...

Carrie - There's a real shift in education at the moment towards STEM and all of these can be taught through the arts which is what we're quite excited about. There's also this shift towards project base learning, this idea that you can actually learn a lot of subjects and a lot of skills just doing one project. It gives you that kind of real world relevance and it makes it engaging for children and they can see the point of it rather than having these separate subjects that don't really mean anything to each other.

Connie - Kind of moving away from that classic blackboard route learning.

Carrie - Precisely, yeah.

Connie - I guess it's rare that a school will be able to do something like this that often. So, how easy is it to get on a smaller scale more application base learning into schools and into kind of day-to-day lessons?

Carrie - I think it comes a lot of it from parents or from the community. I mean, the reason we're able to do this, is thanks to community members like Dave who's here to do the balloon launches. I think schools can actually tap into a whole bunch of enthusiastic groups in science and in technology. Who will come and help them and help them build these projects and show them some real world relevance?

Connie - What the High Altitude Ballooning Society and a computer programming hardware called Raspberry Pi have done is combined both approaches. Pupile can encode the hardware or Raspberry Pi to collect whatever data they want as the balloon flies from A to B. Today, scout leaders and teachers of primary schools and secondary schools are testing it out and launching a Raspberry Pi onto the borders of space. There are 4 groups who will work together to launch a balloon and then again, after the training, when they take their kit, a new learning back to their schools.

Connie - Okay, so where are we going?

Ted - We're heading towards Norwich which is the region in which we think the balloon should come down according to all the predictive software.

Carrie - Okay, but we've also got - we're looking at the software now and we just got our first photo for it, right?

Ted - Yup! It's downloading, sending down photographs that have been uploaded to the internet to a web server and it's also sending its GPS position so we know exactly where it is.

Connie - That was teacher Ted. I joined him and the rest of his group for the chase. It was a long car ride with 3 of us squished in the back and for the most part, it was pretty sedate - driving along as we tracked the balloons ascent 28 kilometres to the edge of space. But suddenly, things started to get a little more tense. The balloon had burst and was falling steadily. We're stuck at a very long traffic light and the balloon is currently at what?

Ted - One and a half kilometres high.

Connie - And seconds from the sea. So, we really want to get there so we can see it land because it could be that it goes into the sea.

Ted - So we can see the splash.

Connie - So now, we really are picking up the speed and it's all got a lot more dramatic.

Luckily, the GPS told us that we had narrowly missed the sea and the balloon fell in land to a large open field where we found ourselves searching for the payload - a small polystyrene box that was attached to the balloon and had all the equipment. Of course, when the kids do it, their payload could land anywhere - from someone's garden, to the middle of a river, to the top of a tree.

Ted - Alright, we need to pull in somewhere here.

Carrie - There's people here. Maybe they've got it there.

Ted - Excuse me. I don't suppose you saw a parachute come here, did you?

Male - No.

Connie - So, this is the radio. Is it buzzing because we're nearby?

Ted - That signal is coming from our spacecraft in this field.

Connie - Okay, we're going to climb the fence. I found it.

Ted - Found it by the look of it.

(Everybody cheering and clapping)

Carrie - This is amazing.

Ted - I can't believe that this has been to space and it stayed on.

Connie - So that was that. In around 2.5 hours, our payload had gone all the way to the outer reaches of the atmosphere and come back down to land in a field near the east coast - quite a day really. Back at base, I got to catch up with James Robinson from Raspberry Pi and find out a little more about what the project would actually do for kids in schools.

James - The aims of the project is to really show young people how the combination of science, technology, math and engineering can achieve really spectacular results. So, there's lots of cross curricular potential with the project. So, you've got the science of the forces that were involved, how we get something from the ground to high altitudes, you've got pressure. There's loads of calculations involved in how we predict the flight path of the balloon so we know we can recover it. You've got the programming side of things so it's the software that governs how the tracker device works and then the other aspects, the arts and the English, and other sort of curricula that could be linked into this. So, telling the story of the journey of the balloon and the items that the kids have placed inside. So yeah, we think it's a really cross curricula project.

35:24 - Students get swabbing for bacteria

Students get swabbing for bacteria

with Lucy Robinson and Dr Anne Jungblut, Natural History Museum, London

The Microverse project launched recently at 130 colleges and schools across the UK. Recruited by the Natural History Museum, London, participanting A-Level biology students were shown how to swab their local buildings to discover which micro-organisms live on what buildings. Project manager Lucy Robinson hopes the data will be academically rigorous and publishable, as she explained to Graihagh Jackson...

Lucy - The Microverse is a Citizen Science project and it came about by one of our researchers, Dr Anne Jungblut, coming to us saying that she wanted to collect a lot of data across the UK on the bacteria and other microorganisms that grow on buildings. She wanted our help in getting members of the public involved in collecting those samples.

Graihagh - And it’s not just member of public. You sort of narrowed down and focused actually into school children, A-level students. So, what would they do? You send them out a pack and then what happens?

Lucy - Schools across the UK signed up to take part. We sent them a pack containing all the equipment they would need and then the schools took that, went outside, chose a building near to them, and they collected 10 swabs of microorganisms from that building.

Graihagh - And we’re standing outside the Natural History Museum today. It’s ample opportunity to take a swab.

Lucy - We can give it a go. So, I've got the kit here that we gave to the schools. So, we can take a sterile swab here and then I need to dip it into the sterile water, and then we can rub it on the wall to collect the sample.

Graihagh - It’s looking pretty grapy already.

Lucy - So, I'm collecting a sample from glass here and you can already see that there's actually black on the white cotton ball bit there. So, we can see some of that obviously is going to be pollution. We’ve got a road nearby, but some of that is actually the microorganisms that are living on that glass.

Graihagh - How do you make sure it doesn’t get contaminated?

Lucy - Yeah. So the school students put on a pair of plastic gloves to collect their sample and then they put the sample straight into some DNA preservative liquid. It captures that DNA and keeps it in a good state.

Graihagh - How many swabs have you got back so far?

Lucy - So, 130-ish schools have taken part and they’ve each done 30 swabs each. So, we have thousands and thousands of these to process, just what keeps Anne and her colleagues very busy in the lab.

Anne - So, my name is Anne Jungblut and I'm a researcher here at the Natural History Museum. So, when we get them back, the first thing is we’re going to freeze them and then later on, we come back to the lab to extract the DNA. Once we get the DNA, we amplify a piece called like the 16S gene which is like a piece of DNA all bacteria have. We amplify it and then afterwards, we sequence this and that allows us to characterise all bacteria that we have from the samples.

Graihagh - Why do you want to characterise all these bacteria samples? What's of interest to you?

Anne - Well, it’s really exciting. So, we have like all these environments but we actually don’t really know what's happening in the cities.

Graihagh - So, once you have the samples you need to amplify this DNA, I'm assuming you’ve done some on the Natural History Museum, what sort of things have you been finding? Any surprises in there?

Anne - So, we have found lots of different species. So, we found for example, cyanobacteria. They're also called like blue-green algae and they sometimes make the walls appear like greenish.

Graihagh - Is that the slimy stuff you often get on when it’s really wet and things become a bit slippery, particularly on wood, I seem to remember?

Anne - Yeah, it’s part of this. So, you have the cyanobacteria and then you also have some micro algae, but they basically make slime.

Graihagh - Anything else?

Anne - We also found some organisms which are potentially interesting for like biotechnology.

Graihagh - When you say use for everything in the lab and biotechnology, what sort of use does it have?

Anne - So like the streptococcus is like an organism that has this enzyme called DNA polymerase which basically helps in the duplication of DNA. So every organism, we all have it, but these organisms, it’s really cool because it’s functional at 50 degrees. And so, when you extract that enzyme, you can then use it in a lab like we do. So, everybody who would amplify DNA in a machine everywhere in the world uses that enzyme.

Graihagh - And it’s just growing casually on the buildings.

Anne - Well potentially. So, we haven't found the exact match, but we’ve potentially found relatives to that species.

Graihagh - Ultimately, you're hoping to publish?

Anne - Yeah and it’s going to be part of I think several really good publications.

Graihagh - It looks like Anne is getting some really interesting results already. What sort of reactions have you had so far from people that have taken part?

Lucy - We’ve had really positive reactions from the students and the teachers that have taken part, in that this is real science.

Graihagh - And I assume this is restarting up as the school term starts and these 130 schools will be moving on with their next set of A-level biology students.

Lucy - So, we’re hoping the project will continue in future years. We’re currently fundraising to keep it going and we’re still analysing the data from last year. So, there's still plenty more work to be done on the data that we’ve got.

Graihagh - Is it only the one propagation about the species? Are you hoping to do more with this and look at how this might affect or impact how we teach?

Lucy - There are two really interesting elements to this project. The first is the actual science research that we’re doing that you’ve heard from Anne about. But the other side is, how do we do science? And so, we’ll also be writing up how we’ve gone about running this project, how we got the schools involved, the much wider benefits of doing that beyond getting our science research. The museum has also reached out to over 100 schools, started a dialogue with those teachers and really, sort of spread the word about what science is about. So that in itself is a really in part of the project that we’re going to be writing up...

41:31 - Is there a shortage of scientists?

Is there a shortage of scientists?

with Professor Stephen Gorard, Durham University

Many science engagement initiatives are based around the idea that we need  more scientists. However, the UK is one of the top countries in the world for STEM graduates, beating the US, Germany and Sweden, and there has been a 39% increase in STEM graduates between 2003 and 2010; which begs the question, is there really a shortage of scientists in the UK? Durham's Stephen Gorard examined the evidence with Chris Smith...

more scientists. However, the UK is one of the top countries in the world for STEM graduates, beating the US, Germany and Sweden, and there has been a 39% increase in STEM graduates between 2003 and 2010; which begs the question, is there really a shortage of scientists in the UK? Durham's Stephen Gorard examined the evidence with Chris Smith...

Steven - No. We found references going back to the 1920s. Certainly, in the post war era, there was a lot of fuss about rebuilding science skills and so on after the war.

Chris - What's driving that then and what's the motivation behind pushing for more people to go into this discipline? Why is it good for the country?

Steven - There is a lack of numeracy in the British industry and the British workforce, and in the academic workforce. It might help with that. It helps people as citizens and as workers to judge the security findings. So, there are all sorts of skills that it would inculcate. On average, they would be likely to earn slightly more than graduates of some other professions. It's also fun. It's interesting in its own sake. It doesn't have to be for a STEM occupation necessarily afterwards.

Chris - So, it's a reasonable thing to go into. It's certainly not going to harm someone to be going into STEM. So, if there isn't a shortage, it's certainly not going to do any harm to have a few more scientists around. What's the evidence that there might or might not be a shortage?

Steven - The problem is not so much the data as the definitions. What's really happened over the last say, 30 or 40 years is the names of things have changed. So, the number of people doing a degree called physics has remained about the same. It's gone up a little bit but not as much as say, higher education participation has in general. What happens, we've got new things which are STEM related, but don't have words like chemistry, physics, and biology necessarily in their titles.

Chris - What about the issue that if you look at the UK's CS report which looked at the issue of how many people are training in science, technology, engineering, maths type topics, and what happens to them? If you train in medicine and dentistry which were included in those figures, not surprisingly, 90 per cent of people who train in those subjects end up working in those subjects. But then you look at things like life sciences or medical training which is basically learning about biology for example, 75 per cent of the people who study their subjects don't end up working in them. So, I would argue that's a bit of a waste.

Steven - But is it necessarily? These people would take their skills to work in other areas. With say, medicine and dentistry, there are clear vocational routes whereas with degree schemes within STEM which don't have a clear vocational trajectory, someone has to make a decision and there will be opportunities, there'll be serendipity, and all sorts of things that will determine why people end up where they are. That doesn't mean that what they've learned will be harmful or useless to them.

Chris - If we look at those figures and say, well, if people are going and working in sectors that are not relevant to a science training, does that therefore give us an indirect measure that there is an oversupply and we don't need to worry about how many scientists we've got. We've got plenty.

Steven - Well, the paper we published in 2011 suggested at that stage and is now been confirmed by more studies that there isn't a huge unmet demand for people in STEM occupations. There is some evidence that STEM graduates earn more in their STEM occupations than they would in other occupations or the non-STEM graduates would. But I don't think the difference is such that their hands are being bitten off. It's not like the market has got this huge unmet demand for scientists.

Chris - If we do a more fine-grained analysis and we look at these people in STEM subjects, if we sort of home-in on how many people are doing physics or doing chemistry or doing biology, is everything a rosy picture or are there gaps in our market where we perhaps should be focusing more?

Steven - There will be small areas. As with anyone, when you're trying fit a certain supply to a set of demands there will be regional, geographical and sector specific shortages. They might be temporary or they might be chronic. We're talking about the overall picture of supply is, I would've thought reasonably healthy.

Chris - What about the international picture? Britain is doing quite well. There are not many countries that have as many scientists per head of population that we do here. Therefore, are other countries actually in a more powerless position than we are?

Steven - I haven't done a lot of international comparisons, but I would've thought we were in a reasonably good position for a developed country. If that's what we're looking for - but it's very kind of a sort of human capital agenda underlying all of the policy about STEM supply. There's also of course the usual agenda of, "We need a scientific literate population." So, a lot of scientific education shouldn't necessarily be aimed at producing people who end up in STEM occupations. And nor is it a waste if people are given STEM educations and don't end up in these occupations.

Chris - I think as the late (Collin Pilinger) said, "It's much easier to turn a scientist into an artist than to teach an artist to become a scientist. So, I think the point perhaps you're saying and I'll just finish on this point because we are short for time is that, actually, giving people a scientific training regardless of what they do with the rest of their life is a good thing to do.

Steven - I would think it's a good thing to do and it could be something that could be adopted in schools in the key stage 5 where perhaps everyone should continue with some element of STEM some study.

47:13 - Seeing science differently

Seeing science differently

with Amy O'Toole, Blackawton School

Iniatives that get students doing real research can clearly alter perceptions of what scientific research actually involves. But what sort of impact is it having? Amy O'Toole is one of the youngest people to have authored a peer reviewed paper when she published a school project, aged ten. She told Graihagh Jackson a bit more about how it changed her perceptions of science...

Graihagh - It’s interesting to think this, ‘are we short of scientists or not’ debate isn't quite as clear-cut as you might have thought. But one thing that really came out in my conversation with Amy, the 16-year-old girl that we heard from earlier in the programme was that these initiatives that get kids doing actual research do give them a clearer perception of what's really involved in science and ultimately, that’s probably just as important. Amy is one of the youngest people to have published a peer reviewed paper, aged 10 and she told me a bit more about the study.

Amy - So basically, we asked, what if bees could think like humans which was extraordinary because they only have something like 3 million brain cells compared to our 300 billion. So, we set them a simple puzzle. And so, we just did this a few times and tested our results and everything.

Graihagh - And do bees think like humans?

Amy - We came to the conclusion that they did especially when solving puzzles.

Graihagh - And you got this work published. You were only 10 years old. How did that feel?

Amy - It was pretty surreal mostly because I didn’t realise the importance of our findings until I was told that I was one of the world’s youngest probably, scientist. The paper itself was downloaded 30,000 times just on its first day. But most importantly, it’s the most read paper biology letters. It’s pretty amazing that not many people can say that they have a published paper in the Royal Society journal, let alone that they're one of the world’s youngest probably scientists.

Graihagh - Yeah. I'm a whole 26 and I can't put any papers behind my name. How did it change how you felt about science?

Amy - Science has definitely changed a lot after doing the bee project. But now that I can see that science is all around us and it’s in every aspect of our lives.

Graihagh - And has it affected what you want to do with your life and your career?

Amy - Yeah, definitely. I want to sort of inspire more kids into science and give them the opportunity that I had because it’s definitely changed my life so much. I was very lucky and I'm very grateful to for giving me that opportunity. I also sort of want to pursue a career in science and technology. So, a robotics engineer or a neuroscientist, which I’d never dreamed of a few years ago.

49:31 - Is there a reason for toenails?

Is there a reason for toenails?

Fingernails seem to have obvious uses but what are our toenails for? Sam Mahaffey and Dr Isabelle Winder from the University of York go in search of a gripping answer...

Sam - Well, this question got us Naked Scientists talking. What is the point of toenails? Gary on Facebook thinks they must’ve benefitted our ancestors at some point, and Gerald says that our nails gives support when gripping. I asked Dr Isabelle Winder, a paleoanthropologist at the University of York to help me answer this one…

Isabelle - Our nails evolved from claws. Primates all have flat nails like ours although not all of them have nails on every finger and toe. The small lemurs and lorises for example have a special grooming claw on some of their toes.

Sam - I'm not sure I like the sound of the grooming claw. How did we go from claws to nails then?

Isabelle - Nails appeared when the early primates grew larger and moved into the smaller branches of the trees where the fruits, seeds, flowers, and insects are. Claws are strong enough to bear the weight of small bodied animals – think of a squirrel. But a larger animal can't put all its weight on small claws so the larger primates evolved a strong grip and fingers and toes that can grasp efficiently instead. We don’t know if this change especially favoured nails or is there a by-product of the evolution of grasping hands and feet? But they're part of the same package that gave us opposable thumbs.

Sam - Okay. Our nails evolved from claws and this was part and parcel of our dextrose hand and feet. But do nails serve any purpose now, other than looking nice when we paint them different colours?

Isabelle - Well, their main job is to protect the sensitive ends of our fingers and toes from damage. They also help us with precision movements. When you touch another object, the soft tissues in your finger push against our nail which provides a solid anchor and enhanced sensitivity. It’s even been suggested that nails may serve us as indicators of health because poor diet and disease often show up in changes to the colour, condition, and strength of our nails. Of course, we can use our nails themselves as tools.

Sam - Okay. I can see why our fingernails would be useful as tools for picking, peeling, and scratching, but what about our toenails? I can't peel an orange with my toenails. Even if I could, I don’t think I’d want to. In fact, it seems like our toenails actually cause us problems like when they become ingrown and maybe we’d be better off without them. Are our toenails at all advantageous? If not, might we one day evolve to lose them?

Isabelle - I suspect you're right that toenails aren’t as useful or essential to our modern lives as fingernails. I think some of the same functions, protection for instance are applicable. But now that our toes have lost their role in grasping, we probably need them significantly less. But personally, I don’t think we’re going to evolve to lose our toenails mostly because to see a change like that, I’d expect there to be a benefit to not having them rather than a small benefit to keeping them.

Sam - So, our toenails might not be very useful to us, but unless there will be some evolutionary benefit to losing them, it looks like they're here to stay. Perhaps Rachel on Facebook is right. Toenails are just something to decorate. I hope that answered your question (Lou Allan). Next week, I’ll be trying to fathom Paul’s question…

Paul - Why do we make mistakes during repetitive tasks?

Comments

Add a comment