This week, London’s latest ULEZ expansion - will it make much difference to air quality? The concerning impacts of poaching, and not just to endangered species, and the curious case of a woman with a worm in her brain.

In this episode

00:53 - Will expanded London emissions zone cut air pollution?

Will expanded London emissions zone cut air pollution?

Frank Kelly, Imperial College London

The detrimental effects of poor air quality on our wellbeing are widely acknowledged by public health bodies. There are 2 main types of air pollution which impact our health: nitrogen dioxide gas, or NO2, and tiny soot particles. Owing to its size, London is a particularly poor performer internationally, nearly always exceeding the safe levels of these pollutants as defined by the World Health Organisation. Motor vehicles are one of the primary producers of air pollution, so reducing traffic emissions is seen as a key way to tackle the problem. The latest ULEZ expansion, now covering the whole of Greater London, is the latest initiative in a 20 year history of congestion charges in the capital. Critics argue that the expansion punishes people with older cars too severely, while others question if it will have much of a meaningful impact on air quality at all. Chris Smith spoke to Imperial College London’s Frank Kelly to hear why he thinks the most recent ULEZ expansion is justified. He leads the London Air Quality Network project, a system of monitors across the city which measure air quality on any given day…

Frank - So when the inner London ULEZ was introduced after it had been in operation for one year, we looked at the data and we found that across all the major roads, the gas nitrogen dioxide had fallen by about 46, 47% compared to the year before the ULEZ was up in operation. So it had a big effect on that particular pollutant. The other one, which we worry about, the tiny particles of dust, the PM2.5's, had fallen as well. Not as much as NO2, probably around 20, 25%. So yes, there is evidence that if you bring in controls to eliminate the more polluting vehicles, then in due course you will get an improvement in air quality.

Chris - But that's been the bone of contention, hasn't it? Because it seems there's almost an arbitrary line in the sand where cars of a certain age can come in, cars of a greater age can't come in, electric vehicles are completely exempt and some people are arguing, well, electric vehicles, we regard them as highly green, but in fact they pollute in a different way. They're heavier, they produce more tire wear particles, they also produce more brake wear particles. So we may just be robbing Peter to pay Paul in pollution terms.

Frank - Well, there is a lot of very solid evidence, which has shown that the exhaust emissions, particularly from diesel vehicles, are particularly harmful to our health. So there is a very good reason to try and control the number of older diesel vehicles on the roads. So that is, I think, a very robust policy. The issue that we have is that we still, yes, we'll replace those older vehicles with newer ones and as you rightly say, any vehicle will produce powerware particles, brake wear particles, and it'll words on the road surface as well. So the actual solution to our air pollution problem in cities is actually not just making cleaner vehicles use the road, but actually to have fewer vehicles using the roads. And that really points to better public transport systems.

Chris - Others have pointed out that there's only so far you can go with stopping people or trying to stop people using the roads because the pollution will still blow in from elsewhere. So unless you've got clean air everywhere, you're still going to get some pollution.

Frank - So it is true that pollution doesn't respect any boundaries. And this is why you really need solutions, not just at the city level but also at the national level. And at the international level, we have to ensure that specific negotiations go on with our neighbours. In particular, we know that in the spring and early summer there are a lot of pesticides and fertilisers used in the agricultural system, not only in the UK but also in Europe. And these can end up being entrained up into the air. They get carried in the winds over to ourselves. So we do need two things to happen. We need improvements in our agricultural systems and emissions and we also need to recognise that we need to do this not just by ourselves, but in combination with our international partners.

Chris - Notwithstanding that, the other thing that people are objecting to is the fact that polluting cars can still carry on polluting. They just pay a bit more. And some people are saying, if we were really serious about the pollution problem, we would just ban them. Whereas at the moment it happens to be a quite convenient revenue stream for the mayor of London.

Frank - I honestly think that that's an unfortunate view to take. The ULEZ would be most successful actually if it wasn't making any money at all, because then none of those vehicles would be on the roads of London anymore. We already have 90% of the vehicles that are compliant and can legally use the roads. We just want to try and remove that final 10% and we're doing that by saying, you can use it if you will pay this extra money. So it's a deterrent. It's not a 'you must stop doing this'.

Chris - And do you think that London is a special case or we're probably going to see this sort of thing being implemented using London almost as a guinea pig in other major cities in the UK in the near term.

Frank - Yes. I think it's 15 cities across the UK which have what are called clean air zones. And they operate in various ways. Some of them, like the ULEZ, will charge a vehicle owner a daily fee if they use their vehicle on the roads. Others will only be in operation during certain times of the day and others will just be a deterrent to certain types of vehicles. I think London is at the vanguard, it is the guinea pig. It is important that London shows that these sorts of schemes can benefit not just simply from an air quality improvement point of view, but actually from a health point of view as well, because ultimately that's why we're going through this angst at the moment. There's 500,000 people with asthma in greater London and many of those require medications on a regular basis and require more medication when pollution levels increase. So ultimately that has to be the benefit. And if London can demonstrate that, then I think others will follow.

08:02 - First ever uterus transplant in the UK

First ever uterus transplant in the UK

Ellie Patterson

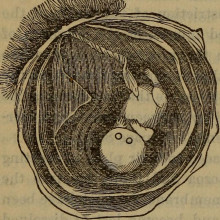

A milestone in UK medicine was reached this week when doctors announced that they had successfully completed the country’s first uterus - or womb - transplant. The organ was donated to the recipient - who lacked her own uterus - by her sister, who had completed her own family. Ellie Patterson is a junior doctor currently working in Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Wellington, New Zealand. She developed a keen interest in the science of uterine transplants from the time that she was a UK medical student and has been following the story over a number of years. She took our own Chris Smith through what the procedure involves…

Ellie - Uterus transplantation is now a proven available treatment for absolute uterine factor infertility, which means that women either don't have a womb or they have a womb which is unable to support a pregnancy. So the vast majority of cases of uterus transplant that have happened, and there's about a hundred cases that have happened across the world, are for women that have been born without a uterus. So that's a congenital reason. The process itself involves IVF as well as the transplant procedure you need to transplant embryos into the recipient. It's a very high risk pregnancy, so there's a lot of monitoring involved following successful pregnancies and live births. If that does happen, patients will need to have the graft removed to avoid having immunosuppression for the rest of their lives.

Chris - And when they actually do the surgery - I'm just thinking of the internal anatomy of the female body, you've got the vagina, the cervix, and then the uterus sits on top - what bits do they take out of the donor and how do they install that into the recipient?

Ellie - You need to take a decent amount of length with the arteries and veins that are going to supply the graft once you've transplanted it in, you need to take supporting structures. So that's mainly the ligaments that are attached to the uterus to be able to fix the uterus in place. The top third of the vagina is taken with the graft and that will be attached to the existing two thirds of the vagina. That will be within the recipient as well to allow menstruation once the transplant has started to work. And also you need that passage away for the embryo transfer after the transplant has hopefully been successful.

Chris - And the recipient, they can't conceive naturally once they've got this in place?

Ellie - They can't conceive naturally because you don't have the connection between the ovary and the uterus. So the patients will need to undergo egg stimulation and IVF prior to the transplant. They'll then have the transplant and their embryos that have been created from IVF will be inserted by embryo transfer.

Chris - And when will the obstetricians say that it's safe to do that? How will they know that the uterus they've put in has been grafted safely and it's healthy and it's capable of supporting a pregnancy in its new home?

Ellie - So in terms of the rejection that is monitored with a variety of different blood tests and also with cervical biopsies. In terms of being able to judge whether the uterus itself is functional, that's partially judged with the return of menstruation, which hopefully will occur in the first few months after the transplant.

Chris - And are there any major risks if you have a baby like this that we have to watch out for or do we think to all intents and purposes, this uterus in its new home should work the right way and it should grow a baby to term that's healthy?

Ellie - In terms of foetal outcomes, it's just really too early to say. There's been about 40 babies that have been born, but seeing as the first birth was in 2014, it's really too early to be able to comment on whether there's any foetal abnormalities as a result of the uterine transplants.

Chris - The surgery in the UK was paid for by donations. It cost about 25,000 pounds were the estimates that I've read. Some people have argued that the woman in question didn't have to have this done. She had her own eggs and her partner was able to fertilise them, producing embryos. They could have asked her sister to be a surrogate, for example. Is this a sensible thing given the risks?

Ellie - Yeah, so this is a concern that some people have raised; this idea of having gestational parenthood as opposed to surrogacy. There are some concerns about whether this is putting too much emphasis on the "perfect" nuclear family and the way that that should be produced. But with surrogacy, there's a lot of ethical concerns that also come with that process. There's a lot of countries throughout the world where surrogacy is actually not legal. So I suppose families are much more limited if they don't have that as an available option to weigh up as well. I think it really should be done on a case by case basis and taking patients' wishes into account. Obviously there's a lot of large surgery involved, which comes with a lot of risk.

13:53 - How hunting and poaching affect climate change

How hunting and poaching affect climate change

Elizabeth Bennett, Wildlife Conservation Society

As you will probably be aware, we are in the midst of a global biodiversity crisis, and one of the regions being hit the hardest are the world’s forests. Not only is deforestation increasing, but the ongoing trade of hunting and poaching is having a devastating impact on some of the planet’s largest and most charismatic species. In fact, poaching is estimated to be driving 30,000 species towards extinction. But now, a new study has just been released detailing that hunting and poaching is not just bad news for the animals themselves, but also the climate. The removal of large organisms is causing more carbon which is normally stored in these forests to be released in several different ways. Will Tingle spoke to the Wildlife Conservation Society's Dr. Elizabeth Bennett.

Elizabeth - The animals that are often the target of hunters because they're big and because they're spectacular, so they provide a lot of food and they also have tusks and horns that can be sold, are the large animals. If you can picture a monkey or a hornbill or a toucan, with big beaks, they can have very large fruits with big seeds and they disperse those seeds. And the trees which have those big fruits and big seeds tend to be bigger trees with harder wood, more dense wood, and therefore they capture and store more carbon. So over time, and it's a gradual process, but over time as those big seed eaters and seed dispersers are wiped out of a forest, then you'll get a gradual change in the tree composition of the forest to smaller, less dense wood trees which store and capture less carbon. So overall, you are reducing the value of that forest to mitigating climate change. Then elephants, which have been really hit very hard by hunting. On top of that, they change the composition of the forest through the way they eat, through their browsing. So they tend to eat smaller, more edible trees, little bushes and that sort of thing, which are more digestible. And that means that you again get a gradual change in the composition of the forest over time so that your big trees, which aren't eaten by elephants, tend to become more dominant in the forest. So again, overall, the impact is that you get a forest with bigger trees, with denser wood, which store more carbon and capture more carbon from the atmosphere. And so that's huge in relation to climate change, particularly because the climate change crisis is so extreme. We want to do everything we can to make sure we have all the tools in the toolbox to address it. And by wiping out some of these wild species, we're removing a tool in the toolbox to capture and store carbon.

Will - How much of an impact on the climate might this be having?

Elizabeth - Various studies have shown that loss of large mammals in different tropical forests around the world can lead to losses of 10% or more of the above ground biomass, the above ground weight of trees in the forest. So that's very significant.

Will - That is extraordinary, isn't it, that 10% of above ground vegetation could be lost due to poaching or hunting. Surely knowing that and being able to quantify that means that we can put more stringent protections in place for these organisms.

Elizabeth - The amount of resources spent on protecting wildlife in tropical forests in countries around the world, and this isn't just in tropical forests, it's wildlife conservation in general, is greatly underfunded and under-resourced around the world, particularly in some of the poorer tropical forest countries. So what this hopefully will do is, firstly, the knowledge that these animals are really important in mitigating climate change, hopefully will influence policies of governments to increase protection of them. But more importantly, hopefully it could influence funding streams. Wild species have no market value if they stay in the forest apart from tourism, which in forest areas tends not to bring in huge amounts of money. But carbon does have an increasing market value. So if the carbon of those wild species, their carbon value becomes a central part of the rapidly emerging carbon markets, that has the potential to raise very significant extra funds for forest protection and management, including protection of its wildlife. And if you have a carbon market for a forest which has its full elephant and primate and bird populations intact, that could raise very significant extra funds. And that's a really exciting potential opportunity.

Will - So as cynical as it sounds, the sooner we can put a monetary value on these organisms, the more likely they are to be protected or worth something.

Elizabeth - Sadly, yes. And it's a monetary value that would be keeping them in the wild, in the forest, for performing their natural functions rather than their market value for hunting them and taking them out of the forest, which is currently the main market value, sadly, that they have.

Will - This shouldn't really be perhaps the main reason we want to keep them alive. We want to keep them alive because they are wonderful and special organisms.

Elizabeth - Absolutely. I mean, every single animal in the tropical forest that we're talking about is spectacular. It's beautiful. It's the result of millions of years of evolution. And the world is a richer place because they're all there.

19:12 - Neurosurgeon finds wriggling worm in patient's brain

Neurosurgeon finds wriggling worm in patient's brain

Kieren Allinson

An operation developed an unexpected twist for an Australian woman recently when the neurosurgeon, working to investigate a large, unexplained lesion visible on her brain scan, pulled out a 8cm long wriggling worm! Not normally an infection seen in humans, the snake parasite had invaded her brain by mistake. Thankfully these sorts of events are rare, but Cambridge neuropathologist Kieren Allinson had a similar run-in with a worm in a patient’s brain himself a few years back. Chris Smith spoke to him about both of these extraordinary cases…

Kieren - This lady in Australia, I think she's 64, and she's had symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhoea, night fevers, headaches, forgetfulness and psychosis, depression, sort of psychological symptoms. And she's presented to hospital in Canberra and she's had a brain scan and that's shown a lesion in her right frontal lobes. That's the front part of the brain and that's the part of the brain that we associate with controlling behaviour, inhibition, normal social behaviours and personality.

Chris - So that would fit with the fact that she had mood changes and some forgetfulness and so on.

Kieren - Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

Chris - So what did they do next then? How did it come to light that there was a worm in her brain?

Kieren - So if normally someone has a lesion like this on a brain scan, it's most likely going to be a brain tumour. Sometimes infections, sometimes other things. She would've then gone to have neurosurgery and they would've operated to remove the lesion and to find out what it is.

Chris - Would that normally come to someone like you if a neurosurgeon does an intervention like that, would they normally send material to a pathologist to get them to tell them what it is?

Kieren - That's right. Yeah. So they'll take tissue during the operation and they'll send that to a pathology lab and then a pathologist like me and look at that on a microscope and try and work out what it is.

Chris - But I gather the neurosurgeon in this instance got something of a surprise and a shock when she got inside this woman's head.

Kieren - Yeah. So incredibly, she pulled out a eight centimetre long, or three inch long, worm, which was still motile, still wiggling about. And that obviously gave her a complete shock. It wasn't what she was expecting. And I think she then began to ring colleagues from microbiology and infectious disease, et cetera, to ask them what to do about this.

Chris - Some commentators have said that is a once in a career type thing, but you have some history with finding worms in people's heads yourself, haven't you?

Kieren - Yeah, that's right. So about 10 years ago, me and my colleague Andrew Dean, uwe were working at Addenbrooke's and we received a biopsy from a neurosurgeon. And it was an interesting case because the guy, he came from Hong Kong, he was a chef there. He also lived in the UK and he had a lesion in his brain, which had been followed up for a few years. And it actually moved. So on the initial scans it was on one side of the brain and a few years later it was on the other side of the brain. And when they finally biopsied it and sent it to us, it was a worm, a different type of worm called a sparganosis. So this was the one time where I've experienced this, a worm in the brain.

Chris - Did the neurosurgeons then realise what they were dealing with?

Kieren - No. So that's the main difference with these two stories. On this occasion, the worm was much smaller. It certainly wasn't eight centimetres long. It was around one centimetre long and very fine and thread-like, and they just put it in the pathology pot and sent it to us until we looked down the microscope, we didn't realise it was a worm.

Chris - How did you then work out what sort of worm it was once you had, this is your worm rather than the one in Australia?

Kieren - Andrew Dean took photos of it on the microscope and he sent those photos to an expert and he emailed back straight away saying, that's sparganosis. But then actually we also took some of that tissue and extracted DNA with a Sanger and they were able to confirm genetically that it had the DNA profile of a Sparganosis worm.

Chris - This is the Sanger Center at Hinxton that helped to sequence the human genome. You got them to read the genome of the worm and therefore work out what it was.

Kieren - Yeah, that's right. Yeah. And it was the first time that species had had its genome sequenced.

Chris - So in both cases we've ended up with weird worms in weird places in the brain, how do we think they got there?

Kieren - So they're both there by accident. Humans are not meant to be the hosts of these worms. The Australian one, the definitive host, the host in which it reproduces, is the carpet python. Small mammals and marsupials eat things contaminated with the faeces of the python. And then they get it and then a python eats them and that's the normal lifecycle. Whereas, in this case I have read that the lady in Australia has gone out foraging for her own stuff from the wild and it's felt that that was contaminated with a larva from the python. And that's how it's got into the human. But it's not meant to and there's no route for it to get from there. Back to its normal host of the python. The worm is not meant to be there and it's kind of reached a bit of a dead end by being there, I think. And it ends up in her brain of all the things you could have in your brain on an MRI scan, when you have a lesion in your brain on a scan, it's actually not a bad thing because it's treatable. And I heard she's doing well with antiparasitic therapy. So actually as gross as it sounds, having a worm in your brain, it's not that bad compared to the other things it could be.

Chris - I suppose there's a risk that she might have more worms. And will they therefore treat her to make sure that she hasn't got more lurking somewhere else that could also find their way into her brain ultimately?

Kieren - Yeah, that's right. So I heard she had lesions in her lungs and maybe in her spleen, but certainly in her lungs. And so she's receiving anti parasitic drugs like antibiotics, but for parasites, anti helminth therapy. So hopefully she'll make a full recovery with that.

Chris - And the worm that you studied, your chef from China, what was his story? How did he get it then?

Kieren - Supposedly from eating undercooked fish, an undercooked frog, undercooked amphibian, which is something that he did in Hong Kong. And that's how it got into him.

Chris - Was the story the same though in the sense that you end up with a parasite getting into the wrong host, us, and because it doesn't know how to behave in us. It does all the wrong things and ends up in all the wrong places.

Kieren - Yeah, that's right. Yeah. So it is an accidental host in a human and it's got nowhere to go from there. It can't get back into its normal lifecycle and it's a dead end really.

Chris - And did he recover with the removal of the worm and then treatment?

Kieren - Yes. You know, he made a full recovery.

Chris - So the odds are quite good for this lady?

Kieren - I think so, yeah. I hope she continues to recover well, yeah.

Chris - Discharged with the advice not to go foraging where pythons have pooed.

Kieren - That's right. Yeah. And that's his advice for anyone. I think.

25:57 - Is it possible to time travel before the Big Bang?

Is it possible to time travel before the Big Bang?

James - Thanks for this one, Daniel. Now, as far as we know, the laws of physics don't allow us to travel backwards in time, only forwards, but we're going to indulge the hypothetical and for that I'm going to need some help. Here's Toby Wiseman, theoretical physicist at Imperial College London.

Toby - The question really is, was there time before the Big Bang? And the answer is unclear, but there are various proposals. So one of them, one that I personally quite like, is one due to Hawking. And Hawking says that actually both time, space and all the matter in the universe was created in a quantum event. And really you can't think of time existing before that.

James - Can I ask you to define a quantum event as best you can?

Toby - By quantum event here, we really mean the universe, if you like, was measured <laugh>. So something somehow came along and measured the universe and forced it into a state. So we know in quantum mechanics you have to measure things and then they decide what they want to do. And the idea here would be that the state it was in is such that when we look at it today and we look back, it appears that it was just created at this instant time along with space and matter. So time was born with the Big Bang, with the whole universe and there was no before.

James - For this theory to be true, we kind of have to be comfortable with the idea that something came from nothing.

Toby - There are indeed other ideas out there. One such as the multiverse, which is quite popular, definitely suggests there was a before. So in that theory, the whole of our universe emerged from a tiny, tiny patch of some rather strange primordial space and time that was cold and possibly very quantum. But then for whatever reason, something caused our tiny patch to suddenly inflate in size incredibly. And then after that, it then heated up and formed what we call now the hot Big Bang. And that's a popular idea as well. The honest truth is we don't really know which, if any of these is the correct proposal at the moment.

James - We tried our best. Daniel <laugh>. I suppose the sticking point here is that this is where we are at in physics, so to speak. We've got our theory of general relativity from Einstein and how we understand spacetime and the physical world at the macro level. And that doesn't quite match up with our understanding of the very small things, the quantum world, which is what we need to get into if we want to understand the Big Bang. And until we find a way of kind of joining up these theories, that question is going to remain a mystery, isn't it?

Toby - That's exactly right. And there are many proposals now, but it's still early days for all of them. And perhaps one day we'll know the answer.

Comments

Add a comment