Malaria bites back, and the lunar base race

In the news podcast, what's causing the uptick in malaria cases in Africa? Also, scientists show statistically that the sex of a baby at birth is not random, and South Korea joins the throng in the race for settling on the Moon. Then, we hear how computer scientists are programming ethical AI to explain its decision making, and, sticking with AI, what are some of the environmentally friendly projects seeking to offset machine learning's vast energy consumption?

In this episode

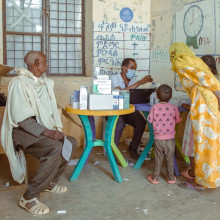

01:04 - Are USAID cuts leading to more malaria cases in Africa?

Are USAID cuts leading to more malaria cases in Africa?

Jane Carlton, Johns Hopkins University

Malaria is a deadly disease caused by parasites spread through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes - mostly at night, and mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. Cases are both preventable and treatable, but only with sustained funding for mosquito bed nets, insecticides, testing and treatment. However, the numbers are rising fast. Zimbabwe has seen a tripling of infections within the past year, and other parts of the continent are experiencing a similar uptick. One contributor is funding cuts in the United States. Washington has long been the biggest backer of global malaria programmes, but that support has been curtailed. Another factor is that a new species of mosquito vector has stepped into the ring. Jane Carlton is director of the Malaria Research Institute at Johns Hopkins University…

Jane - It's a species called Anopheles stephensi and it's usually found in cities and urban areas in Asia, and it's moved from Asia into the African Rift Valley countries, in particular Ethiopia. This was first found a couple of years ago, so in fact we think the invasion happened perhaps even earlier than that. This is very worrying because it could potentially lead to an increase in malaria cases.

Chris - Do we know why those mosquitoes are able to do what they do?

Jane - The Anopheles species of mosquito which transmit malaria are very prone to becoming resistant to the insecticides that are used either on bed nets—one of the main control methods in many African countries—but also what's called indoor residual spraying, which is the spraying of insecticide either indoors or outdoors on particular structures such as houses. So it's the fact that the mosquito becomes resistant very easily to these formulations of insecticide, which is very worrying.

Chris - Obviously a lot of research that goes into this gets funded from the US. How has the withdrawal of funding—or a lot of the funding being chopped recently—impacted things?

Jane - Terribly, it's awful. The USAID, which was the major programme that the US funded, for example in 2024, provided 270 million dollars for Zimbabwe—just one country—for their health and agricultural programmes. That has pretty much been disbanded now. In particular, the President’s Malaria Initiative, which distributed bed nets, anti-malarial drugs, methods for detecting the parasite, rapid diagnostic tests—all of that has now stopped. Many of these African countries are very worried about what the future is going to hold. It's very unfortunate the way this was done as well. It wasn’t a decrease over time, it was very much a sudden death of these programmes. And now that the malaria season in many African countries is part way through or starting—because of the rainy seasons—we're really starting to see an increase in cases, particularly in Zimbabwe, as you mentioned.

Chris - Do you anticipate, though, that this won’t just be a problem for, say, Africa? Because the thing about infectious diseases is that while they may have a hotbed in one geography, they don’t have to stay there. Very often they will spread, and there are repercussions for other countries, including those that would regard themselves as not really at risk to start with—like America.

Jane - Oh yes, that's very true. In fact, two years ago—I think it was in 2023—we had 10 cases of what's called locally acquired malaria in the United States, several in Florida, and one in my state, Maryland, too. That was unprecedented. We've not had locally acquired malaria cases in the US for the past 20 years. That’s because we do have the right mosquitoes—Anopheles mosquitoes—to be able to transmit malaria parasites. US citizens, when they travel abroad—perhaps back to their original home countries, or for work, or even in the military, for example—will pick up those malaria parasites and bring them back to the US. If a mosquito then bites them and picks up the parasite, it can then transmit it to someone who's never even left the country. So if the number of malaria cases starts to increase in African countries, there’s a possibility that the number of people bringing malaria parasites back into the US will increase. That could potentially lead to more malaria cases.

Chris - Particularly with a more mobile population, because not only are there more people on Earth now, they are travelling in unprecedented numbers. I mean, the figures I've seen quite regularly pop up as something like a million and a half people airborne around the planet on aircraft at any moment in time.

Jane - I think globalisation, as we know, also includes increased travel, which I actually think is, in the long term, a very good thing. But of course, infectious diseases and the vectors—the mosquitoes that carry them—don’t recognise boundaries at all. So you're absolutely right.

Chris - And what do politicians say when you put this to them and say, look, this can be regarded as almost like homeland defence? It’s almost like a security blanket. Chopping this off is punching a gaping hole in that sort of defence—not just for America but for the entire world. So why are they persisting in this course of action?

Jane - It's so short-sighted. It really is. In the long run, I think it's just going to turn around and bite us on the backside. I don’t understand it. I don’t really want to comment on why I think it’s being done. I also know that the international aid budget the US provides is really very small. To target and remove that is incredibly short sighted, in my view.

Chris - So what can we do? I mean, we are where we are. America is where it is. What sorts of things can be done to mitigate the impact of this?

Jane - Well, I know many African countries are now looking internally to see whether they themselves can take over their procurement of bed nets and other control methods. But many of these countries have economies already pushed to the limit. I know Nigeria is another example—it has increased its budget this year in order to provide bed nets, drugs, and other methods of malaria control. Apart from that, I’m not sure what else can be done, really. Many of us here in the United States are continuing our research programmes as much as we can. Obviously, there are some issues with the National Institutes of Health and the funding of those international projects. But we’re just really trying to push through and see what we can do over the next few years to continue to support the work on malaria control in endemic countries.

08:34 - 'Weighted coin toss' determines baby's sex at birth

'Weighted coin toss' determines baby's sex at birth

Jorge Chavarro, Harvard University

Now, is the sex of your baby really just down to chance? For years, scientists assumed it was, and the odds of having a boy or a girl was 50/50. But a new study from Harvard suggests some mothers may be more likely to have a slew of children of the same sex. We’ve all come across those families with a long line of boys because they kept trying for a girl, and vice versa. Well, after analysing data from over 60,000 women, researchers found the odds might not be completely random after all. They’ve even factored in parental preferences - and it turns out, the chance of having a boy or a girl might be more like a weighted coin toss. And maternal age could be part of the equation. Here’s Jorge Chavarro at Harvard’s School of Public Health…

Jorge - Everybody has the experience of knowing families that happen to have only boys or only girls. And people often wonder, well, is this a coincidence? Sex is supposed to be determined by the sperm at fertilisation, where you have either a Y chromosome or an X chromosome. You would expect that the distribution of sex would be essentially random. But the fact that we see these families that have only boys or only girls so often makes you wonder whether or not there are factors within a couple or within a woman that make it more likely that a couple is going to have either more boys or more girls.

Chris - So how have you looked at that then? How have you done the study to try to find out what's going on?

Jorge - Right. So we used data from two very large studies in the United States: the Nurses' Health Study and the Nurses' Health Study 2, where we had information not only on whether or not women had been pregnant throughout their life course, but also, for each of their pregnancies, whether it had been a boy or a girl. That is very useful because it allows you to look not only at the distribution overall, but also at behavioural factors. So, for example, if you have a boy and a boy, are you more or less likely to decide to have a third child to try to balance the family and have a girl? Or are you more likely to stop? And if things are essentially random, let's say you have a family of two, you should have approximately equal numbers of boy-boy, girl-boy, boy-girl, and girl-girl. Those four combinations should be approximately identical. And what we see is that they’re not. We see a very clear pattern where people are stopping when they have children of at least two sexes.

Chris - Right. So something is potentially biasing things, and then human factors kick in and attempt to reset the bias—is what you're saying these numbers show us.

Jorge - That is exactly what these numbers are showing. And other people have shown this too. Some of the first researchers who wrote about this called it "coupon collecting", right? It is more common in modern times, when people tend to start having children later in life and tend to have smaller families. It is much more common than if you look at, for example, historical data going back to the pre-20th century, when there was less control over how many children you were going to have over a lifetime and when or how you were going to space them.

Chris - Obviously, there’s a behavioural aspect to this. But as you said, there’s something loading the coin. So there's a bias which is there biologically. So what is that? How does it work? And how can you get to that?

Jorge - We wanted to understand if there was something other than behaviour, which led us to do several types of analysis. One was: OK, let's do all this analysis excluding the last birth, because the last birth would be the one most likely to be behaviourally driven. Do we still see the same signals? And we do. Then we wanted to explore to what extent different characteristics of the mothers might be associated with the chances of having only boys or only girls. And really, the only signal that was quite robust—regardless of what analysis we were doing—was maternal age. What we found was that women who started having children later in life—and “later in life” is not that late; our “late” category was over 28 years, compared to having your first child before age 23—even that small gap was associated with having only children of one sex. And the signal was stronger for having only girls. What exactly is that signal of age? It’s unclear. One possible interpretation is if you start later, you run out of time for having children faster. But it's also possible that age is capturing age-related factors we do not yet understand. For example, one of the limitations of our study is that we do not have data on the fathers. But we know that within couples, age is very highly correlated. So it is possible that maternal age is actually capturing factors associated with paternal age that may be influencing the determination of sex at birth. And we have no way of differentiating those two alternative hypotheses.

Chris - Other ways that we can get at genetic traits—you can comb through the entire genome, looking for markers that crop up more often in groups that do have a trait compared to groups that don't. It doesn’t tell you what the gene is—it tells you where in the genetic code something might be influencing the equation. Have you used a technique like that and looked at this?

Jorge - That is actually one of the things that we did in this case. We did something called a genome-wide association study. And we did identify that there are a few genetic signals associated with having only boys or only girls. But the few genetic hits that we identified have not been described before as having anything to do with embryo development, ovulation, or oocyte development. So it is difficult to assign a specific biological function to the genetic signals we're identifying.

Chris - Does this tell us, then, that the couples who are falling victim to the gambler's fallacy—where they keep going because there's been a load of boys and the next one’s got to be a girl—they're probably victims of that and should probably quit while they're ahead?

Jorge - We actually provide estimates of that in our paper. And I think the bottom line is: it is not random. It is not a coincidence that there are families that happen to have only boys or that happen to have only girls. It’s not like if you've had two boys, you're all but guaranteed to have a third boy. But it’s more like 60-40—it’s not 50-50. So if you want to take your chances, you should know that you are probably taking your chances with a weighted coin, as opposed to a completely unbiased one.

17:00 - South Korea enters the lunar base race

South Korea enters the lunar base race

Richard Hollingham, Space Boffins

South Korea has said it wants to establish a lunar base by 2045. The proposal - which is part of a wider roadmap unveiled by the Korea AeroSpace Administration - will include missions in low Earth orbit, microgravity research, and solar science. With renewed lunar ambitions from the US, China and others, it appears that the new space race is accelerating. But is this a realistic prospect? Here’s Richard Hollingham from the Space Boffins Podcast…

Richard - South Korea has got a track record in space. In fact, it has a satellite around the Moon right now, and it has had one astronaut—but only one astronaut. It doesn't actually have a human space programme at the moment. Of course, the US has its plan to go to the Moon, but no firm plans to build a Moon base yet. There's Russia. I think the most serious contender is probably China, and then other nations like India, the Arab nations—and remember, they have a huge amount of money—are also keen on exploiting and exploring the Moon. So I think this will happen. It's just that I don't think it's going to happen immediately.

Chris - What is the draw, though? What is it about the Moon that they are potentially seeking to exploit?

Richard - I think, as much as anything, it's a political ambition to go to the Moon. It's a political ambition to put the flag there, to explore beyond the Earth and to exploit beyond the Earth. It's also a stepping stone. So if we imagine humanity leaving the Earth, heading to the Moon, then maybe exploiting asteroids—now, there is money to be made potentially with rare earth minerals and just metal in asteroids—and then the next stepping stone on to Mars. If you can't live on the Moon, there's no way we can sensibly look to go to Mars and move beyond the Earth. A new golden age of exploration, of—use the word hesitantly—colonisation, and just moving out beyond the Earth into the wider solar system.

Chris - Have we got the first clue, though, how to actually build a viable, sustainable base on another celestial body like the Moon?

Richard - Sort of, yes. One thing that's been talked about—but we don't know these exist, or we don't have exact proof they exist, we haven't seen them—is that there are probably lava tubes on the Moon. So we could live in lava tubes, effectively living deep underground on the Moon. The European Space Agency has actually done a lot of work on Moon bricks—sintering bricks, essentially making bricks out of lunar dust, very much like you'd make a brick on Earth. And using the power of the Sun on the Moon, focusing that—I've actually been to the facility in Germany, and it does look like a sort of Bond villain lair, with this giant mirror focusing a beam of light. I think it's The Man with the Golden Gun, actually. Very similar to that—focusing a beam of light to create really intense heat, and just blending together—sintering, they call it—Moon dust into these quite ugly bricks. And then the idea is you sort of join them together. You have kind of bricklayers on the Moon—probably robotic bricklayers—that join all these up, perhaps over some sort of airtight inflatable. So an airtight inflatable they live underneath, and then these bricks around the outside. And, I mean, maybe a window so you can see out and see the view of Earth. So there has been a lot done on this, and it would make sense. And it's what they say about either living on the Moon or living on Mars—you've got to live off the land. Otherwise, you've got to carry everything from Earth. That's going to cost a huge amount of money to take something to the Moon. Whereas if you can live off the land—if you can use lunar dust, if you can use water on the Moon to drink and maybe provide oxygen—and then recycle as well. So any bits of stray spacecraft kicking around, you rip them up, melt them down, and make something else out of them. So that is the potential. So we sort of do know how to do it, and I think we could, but it's going to take a lot of will and an awful lot of money.

Chris - Well, on that point, most space activity is collaborative—because it involves a lot of know-how, it involves a lot of risk, and people like to share that risk, both in terms of sharing the brainpower and the cost, and the technological demands. So is South Korea just throwing its cap in the ring and saying, “We'll team up with people,” or are they saying, “We want to go this alone—this is our single-minded, single-country ambition”?

Richard - I wonder if it's sort of saying, “Well, look, we want to be in this as well,” and they will join with one of these blocs that's emerging. So at the moment, we've got the Artemis bloc, which is NASA's funded project to return to the Moon with astronauts—Europe is part of that. Of course, the US used to collaborate and work with Russia—I mean, it still does on the space station—that's not going to continue with the Moon. So you've got China as this other bloc, and then where does South Korea go? You could imagine a third bloc emerging, where you had South Korea, India, African nations, and maybe Arab nations—with all the money—as this third bloc also going to the Moon. Or maybe South Korea will partner with China or with Artemis. So it's really interesting—these geopolitical blocs on Earth joining together to work in space.

Chris - And on that, when they get there, who owns the Moon? Do we have a sort of legal framework for this, or is this literally a race, and whoever plants their flag—that's their bit?

Richard - Yeah, it's a really interesting question, actually. A lot of lawyers are working on that. When you look at the various agreements—there are lunar agreements, there's the Artemis Accords—and you look at who the signatories are, and it's always all the signatures apart from the key people who are actually doing the things. So the Artemis Accords, for example—which is peaceful cooperation in space, the way we would operate on the Moon—that's not been signed by Russia or China. So potentially, they're all aiming for the same place—the Shackleton Crater on the south pole of the Moon. You could actually imagine a US base with maybe some Japanese astronauts there, European astronauts, Canadian astronauts—and then on the other side of the crater, or a few hundred metres away, a Chinese base with Russians—and neither talking to each other. I mean, that's exactly what's going to emerge at the moment.

23:58 - 'Ethical black box' forces AI to explain itself

'Ethical black box' forces AI to explain itself

Alan Winfield, UWE Bristol

This work was carried out with the support of UK Research and Innovation.

Black box flight recorders are usually associated in most people’s minds with air crashes. But one expert believes something similar could help us understand what goes wrong when robots malfunction. It’s the brainchild of Alan Winfield who has been developing what he calls an ‘ethical black box’ - which can log a robot’s decisions and actions in real time. As we move into an era where artificial intelligence is increasingly calling the shots, knowing how systems arrived at their decisions will become more mission critical. Will Tingle…

Will - Ever since the 1960s, planes have been fitted with a black box, a data recorder that takes in flight data like altitude, aircraft speed, and direction. In the event of the unthinkable, this data can be salvaged and used to ascertain which parts of the plane or the crew were at fault. Data recorders are now found in machines across the world, from the air to the land, but our machines and robots are getting smarter, so to speak. More of the impetus is being put on the machine to make the decision, a decision which could be life or death. But the way that a lot of AI makes decisions is not well understood. Creators of large language models don’t always know what information their model used to produce its output, for example. So going forward, will there be a need for an ethical black box, a data recorder that looks at data fed into a smart robot to see what informed its decision? I went to see Professor of Robot Ethics, Alan Winfield. Alan has spent decades conducting research on robots and ethics at the Bristol Robotics Lab. I began by asking him how exactly you go about building an ethical black box.

Alan - It's actually conceptually rather simple because it could be a software module, unlike a flight data recorder, which of course has to be physically very robust. Most social robots don't need that, so it's essentially a software module.

Will - If we took a smart robot in a hospital, what kind of information/data would you be anticipating as being fed into that black box?

Alan - It's essentially everything that we possibly can capture of where the robot is in the world, what its movements have been and are, what decisions it's making, and the interactions that it's having with the human beings around it.

Will - The whole point of this ethical black box is therefore to understand why the robot made its decision. Is the point of that then to create almost an accountability, to be able to say that this robot made a decision that we do not agree with, that perhaps cost a life or caused an infirmity that was avoidable? And because of this particular input of information here, we can see that it made that and that needs changing.

Alan - Yes, that's right. I mean, essentially the reason for accident investigation, and this is true for aircraft and vehicles and so on, is essentially to ask three questions. What went wrong? Why did it go wrong? And how can we fix the problem to make sure it doesn't go wrong again? So the ethical black box for robots and AIs has exactly the same motivation. It's about the reduction of the likelihood of accidents and the mitigation of those accidents too.

Will - So are these ethical black boxes currently being made?

Alan - A few, yes. So obviously, we've designed and built several EBBs in the lab, and at least one, if not two companies are also building EBBs for their own robots. And in fact, one company, a very highly regarded company called PAL Robotics, they are certainly developing an ethical black box for their robots.

Will - To put these EBBs to task, scientists at the robotics lab devised a series of tests to see if data stored in an EBB could inform a fault in a smart robot. If a child was suffering from signs of psychological distress, could it be put down to a smart robot dog that suddenly became aggressive? If an elderly woman was found collapsed, could it be ascertained if her assisted living robot didn't raise the alarm? Could an EBB shed light on why a movement exoskeleton might stop? And could a black box suddenly stop functioning? These were real simulations played out by actors, but crucially, to keep things unbiased, the investigators had no idea what had actually happened. So were these black boxes able to help suss out what was responsible?

Alan - Yes, they were. And in fact, it was very clear that they couldn't have actually figured out what was going wrong without the EBB. They would have a fair idea, they would have good guesses, but there would be no way of verifying those, if you like, educated guesses. So the EBB turned out to be absolutely essential. We realised very early in the project that the EBB can be used as an explainer, not just as a recorder, an explainer that can be used more or less in real time so that you could ask the robot, why did you just do that? If, for instance, the user of the robot is puzzled, the robot should be able to explain why it did that thing because it has an EBB. And the second thing, which is a little bit more tricky, is you could say to the robot, what would you do if? In other words, robot, what would you do if I fell on the floor? Or robot, what would you do if I forgot to take my medicine? These are fantastically important and powerful extensions of the EBB. And essentially my colleague has this wonderful project called PACR in the lab, which is developing those explainer functions.

Will - And this seems particularly pertinent going forward because obviously those simulations that you ran were with hard physical robotics, but AI is taking over the world. There's no real other way to put it. And stuff like large language models, ChatGPT, it is still not entirely certain where they're pulling their information from. Do you think going forward that this is essentially a necessity for us to be able to ethically use stuff like this, which has such a large net that it casts that we don't even know where it's coming from?

Alan - No, I completely agree. I mean, if we are really serious about using AI for consequential applications, what I mean by that is applications on which lives depend. So a very good example would be diagnostics, medical diagnostics or clinical diagnostic AI. It's incredibly important to the clinician that the diagnostics tool should be able to explain why it reached that particular decision. Similarly, if your welfare payments suddenly get stopped and it was an AI that made that decision, then the AI should be able to explain why, what was the rationale? So these are really important things. There needs to be transparency of decision-making. And the only way you can do that is to have that process, the process that led up to that decision being recorded.

31:45 - Is AI all bad for the environment?

Is AI all bad for the environment?

James Tytko took on Geoff's question, speaking with University of Cambridge scientists harnessing neural networks on projects to protect the planet...

James - Thanks for sending that in, Geoff. You make a salient point about the environmental impact of AI. While AI is undoubtedly improving medical science and our productivity, the infrastructure behind it consumes vast resources—especially energy, but also water and raw materials such as rare earths. There's no getting away from the fact that we need to find solutions to decarbonise this booming industry. But following my conversations with some scientists here at Cambridge, I've found there is room for optimism about what AI can do to benefit the environment as opposed to harm it. First, I spoke with Ronita Bardon, Professor of Sustainable Built Environment and Health. She's developed an algorithm to reveal the heat loss from almost every home in the UK. Trained on satellite images and previous energy audits, the tool is helping identify the homes which could be prioritised to improve their performance.

Ronita - One of our main motives for the project was to look at how we can decarbonise our built environment, which is one of the biggest energy guzzlers. But this is not a very easy task. You typically ask a person, how much do you think it would cost to completely decarbonise your house? People will have absolutely no idea. And it's not just individuals—those who build homes may not have the correct estimation either. That's primarily because we do not have a very accurate estimate of the total amount of heat loss each building experiences during the winter months, when we are cranking up our heaters to keep our homes warmer. So this whole estimation—doing it at a large scale, faster, with more accuracy and information that actually feeds directly into policy—only AI methods can help us achieve that. It removes the tediousness; it removes the resource requirement that you would need if you had to conduct energy audits for every building in the UK.

James - Doing this the old-fashioned way, where a professional auditor inspects properties and awards them an energy performance certificate based on features like the age of the property and the type of insulation in place, would take thousands of assessors thousands of hours.

Ronita - I'll give you a real-time picture. If you want to get your house audited to get an EPC rating, typically it’ll take you three days—even excluding the days needed to plan and book it. Here, we can do it in a couple of minutes. We've generated an interactive map, which is accessible through our website, and you can actually explore whether a particular postcode is more liable to lose heat than a neighbouring one. That helps not just with policymaking, but also enables individual homeowners to make more informed decisions.

James - Ronita Bardon there. And that's not all. Aside from attempts to tackle energy concerns, AI is also putting the turbo boosters behind other environmentally conscious initiatives. I next spoke with Professor Bill Sutherland from Cambridge’s Department of Zoology. He's the brains behind the online tool Conservation Evidence. Over the past 20 years, an international team has combed through over a million research papers, looking into the effectiveness of actions to improve the prospects of hundreds of species. The result is a readily understandable ecological encyclopaedia. But now, Bill and the team have been leveraging AI to significantly broaden the pool of relevant research.

Bill - The interesting thing is that we've repeated a review we did. We did a review of all the possible measures for looking after the Lepidoptera—that's the butterflies and moths. And we repeated that using a large language model for the same set of journals. It found 97% of the papers, which is very impressive. But the really impressive thing is that it found other papers as well—quite a large number of other papers. Whenever people do what's called a systematic review—this is a standard approach in medicine and in many other fields—the approach is that you look at the title, and if the title looks promising, you then look at the abstract and decide whether or not to include it. But there are actually a lot of research papers where an action is tested, yet it's not mentioned in the title or the abstract. So there’s a lot of literature that gets missed, which large language models are able to find.

James - Broadening the scope of studies enhances the evidence base for species-saving interventions. Thanks to Bill Sutherland. So Geoff, while environmental concerns around AI’s energy appetite absolutely need to be addressed, I hope that's given you an idea of how scientists are already finding a whole host of applications for using deep learning to look after the planet.

Comments

Add a comment