Measles outbreaks, and terrorist chatbots

In this edition of The Naked Scientists, What can be done to reverse a dramatic rise in measles cases around the world? We’ll also be exploring Japan’s susceptibility to incredibly powerful earthquakes. Plus, what may have prompted early humans to adapt the way they communicated...

In this episode

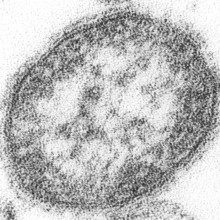

00:54 - Measles cases up 3000% in Europe in 2023

Measles cases up 3000% in Europe in 2023

Chris Smith, University of Cambridge

Top health officials have expressed concern over a significant surge in global cases of measles. Infections have been growing at an alarming rate since 2022 and the World Health Organisation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States say that millions of children are vulnerable to the potentially fatal disease. Our regular host and Cambridge University virologist, Dr Chris Smith, has the story...

Chris - Measles is a really horrible infection and it's probably one of the most infectious diseases that we know about. Most people have heard of the 'R value.' This is the number of people that each infectious case of a disease causes, how many people you give your illness to. And for flu and for COVID, it's 2 or 3. For measles, that number is 20. So it's extremely infectious, which means it spreads incredibly rapidly when you get a case of this. It has a short incubation period of a week or two, and people begin to feel unwell about a week before they get the rash. And they have this bright florid red rash all over their body for up to a week. And then they get better. And the problem with measles is that not only is it a really nasty infection when you have it - very high fevers, sore eyes, bad cough, and in some instances it also causes inflammation of the nervous system up to years later. But the damage doesn't stop there because it also has this bizarre effect of wiping clean your immune slate. It basically introduces immune amnesia. So if you look at someone who's been infected with measles, their immune system has forgotten how to fight off all the things that you've spent the previous part of your life learning to combat and becoming immune to, so you can then start to catch loads of stuff all over again. And that means that you have to live with the legacy, not just of having had a bad dose of measles, but catching things you thought you'd consigned to immune history. So it really is a nasty infection. And around the world, maybe as many as 150,000 people die of this every single year. It's not to be taken lightly.

Will - And the WHO is saying that there's been a 30-fold rise of measle cases in 2023 in the European region. What is behind such a dramatic rise in cases?

Chris - The WHO actually went further than that. Hans Kluge, who's the director of the European region of the WHO, points out that there've been a 30-fold rise, but 30,000 cases of measles, of which 21,000 have led to hospitalisation. And most of those have been in young children, 80% of them are in kids. And they attribute this really big surge recently, which we've also seen here in the UK. We've seen an increase of hundreds of percent in cases in the last year or so. We attribute this chiefly to a reduction in vaccine uptake. People are not vaccinating at a sufficiently high rate to stop the disease transmitting. Measles is incredibly infectious, which means you have to have very high levels of immunity in the population to reduce the chances that someone who's got measles can run into someone who can catch measles and maintain a chain of transmission. And that's herd immunity. And unless 95% of people are immune to measles in a population, it can still spread. And because our vaccine uptake rates have, across the world, sagged considerably. And in some parts of the UK sagged to about 60 to 65%, well down on the 95% we need, this is why we're now seeing increases in cases and a high likelihood we're going to get big outbreaks. And when you couple that to the fact that there's also a resumption in global travel off the back of COVID, we are now brewing up a perfect storm where we've got cases rising, people moving around the planet with measles and they're landing in an area where the outbreak can take root. And that's what's got people worried.

Will - We were sitting here maybe less than a few months ago in this exact same position talking about chickenpox and the need for a push for vaccinations. It seems like we're on almost a carousel wheel of diseases spiking. And you say it's obviously due to a lack of vaccination. Are the doctors having to counter the misinformation behind this sort of anti-vax movement as well?

Chris - We are not sure exactly why vaccine uptake rates have dropped, but there are probably a number of factors. One factor is that people are perhaps having vaccine fatigue off the back of COVID. The second factor is that when you look at who is not vaccinating, it's not a comprehensive thing across the populations of the world. In places like London, it's specific parts of London and specific communities. And this means there may well be misinformation, there may well be a lack of information in those communities that mean that people are not doing the things that other parts of the world have been and should be doing. And also the populations are quite mobile. We are seeing this in communities that tend to come and go, or are newcomers to a territory or a country. So they don't necessarily come from areas where there has been good vaccine uptake. And then there's the disruption caused by the pandemic, where some vaccine processes and procedures fell to the wayside in order to combat COVID. And people missed the boat and they haven't gone back and caught up. And all of that is adding up to a reduction in vaccine uptake, which is now leading to many, many people. I mean, we're talking about outbreaks in London of as many as a hundred thousand people if it really took off because there's so many people in one particular geography all in contact with each other, which means you could get an explosive outbreak. And this is probably why we are seeing a movement across the world of numbers in the way we are.

Will - So we've got, unfortunately, immovable things like population density, but also very real things you can do like getting vaccines. Is there any advice out there as to what you'd give to parents that they can do to protect their children from measles?

Chris - Best piece of advice anyone can offer is that vaccines are really, really effective. But you've got to have them. And they're really effective at any age. So even if you didn't have your MMR vaccine as a kiddy, it's normally given around one year of age and then there's another dose given just before you start school. Even if you've missed that cycle of immunisation, you can go back and have that at any point in your life. So if you think you might be vulnerable to measles, or your children haven't been vaccinated, or they missed a dose, please go and get a dose of MMR. This will stop you catching measles and stop you passing it on to somebody else.

07:16 - 7.5 magnitude earthquake strikes Japan's West coast

7.5 magnitude earthquake strikes Japan's West coast

James Jackson, University of Cambridge

Authorities in Japan have confirmed that dozens of people were killed when a 7.5 moment magnitude earthquake struck the Noto peninsula on New Year's Day. The island nation is located in one of the most active earthquake zones on earth. So, what happened, and how does Japan cope with such frequent and powerful tremors? Here’s James Jackson, a professor of active tectonics at the University of Cambridge.

James - This earthquake was relatively unusual in Japan in that it was on the West coast of the main island, Honshu, rather than the east coast. So the big earthquake in 2011, the Tohoku earthquake which damaged the nuclear power station at Fukushima, that was on the East coast. And what's happening on the East coast is that the Pacific floor is sliding underneath Japan. And that's happening quite quickly, geologically speaking, at about eight centimetres per year. And that makes very large, big earthquakes under the water and that's why you get big tsunamis. This earthquake was on the West coast of Japan, where that process is not happening. There's nothing sliding back into the earth. The earthquakes are pretty shallow and instead what they represent is Japan being squeezed. It's being crumpled up. So it's not just the escalator sliding underneath Japan, but as that happens, Japan is being squeezed. And occasionally you get faults which pop up along the west coast. And that's what happened this time. And it's happened before the last time there was one this size on that same area of the west coast was in 1964 at Niigata. And that one, the fault was also offshore. So it made a tsunami about five metres high and it killed about 40 people. But this one is about a hundred kilometres down the coast. And as far as we can see, most of the fault which moved was onshore. And that is why there's not really been a significant tsunami.

Will - And you mentioned it then, but it's something that stood out to me that was quite interesting is, as you said, the epicentre of this earthquake was quite shallow. It was only about 10 kilometres. For reference, the 2011 earthquake in Japan was at a depth of 29 kilometres. Does the depth at which the quake takes place have any effect on our experience at the surface?

James - Both of those are relatively shallow. But on the East Coast, the escalator, as it goes down underneath the east coast, goes down as far as 670 kilometres. So you get earthquakes all the way down, because as the escalator, if you like, goes down it also breaks up. And so you get deep earthquakes all the way down there, all those earthquakes. 20 is not going to make much difference frankly, whether you're at 30 kilometres or 15. But it does make a difference if you are 600 kilometres down where you are, even at the surface, so far away nothing really is going to do anything to you.

Will - Japan is no stranger to earthquakes. This is the 14th above magnitude 5.5 in the past 10 years alone. And as you've spoken about the remarkable area in which Japan sits is probably the reason as to why they get so many. But how do the authorities there try to manage the risk for events with such little warning?

James - There are a number of interesting points about this. Firstly, Japan is curiously helped by there being so many earthquakes. Even on the west coast, where they're not that frequent. But between the 1964 one and this one, these are two comparable earthquakes, there were probably half a dozen or a little bit smaller, but enough to shake you up and really scare you. So when you say to people in Japan, 'earthquakes are a problem. You need to do something and make everyone safer and your houses better,' it's not a theoretical discussion. They know this will affect them in their lifetime. This is not something you can say maybe my grandchildren will have to think about. No, it will affect them for sure, but also you and your children. So that means it's really at the forefront of people's consciousness and that's a big help. Japan is indeed very resilient to these things. But that's not chance, that's the result of decades of careful hard work, finding out what the problems are. Lots of conversations between the public, public administrators responsible for public safety, and the scientists, and the engineers. And again and again, earthquakes in Japan show that the architects and engineers can design things which will stay up. And the issue is always, when these buildings are built, do the constructors, the building people, actually follow the instructions precisely. It really matters that you don't cut corners to save time and money because anything you do will weaken that original design. But if you follow it precisely, the buildings are likely to be fine. And that is the message again and again from Japan. These things are sort of a quiet triumph of the integrity of the building industry in Japan, which is much admired and respected around the world because in the rest of the world it really isn't much like that. It probably is getting there in places like Chile and New Zealand. But that is a huge achievement.

Will - And as you say, we are still very much in the process of finding out what's happened, search and rescue, that sort of stage in development. But in the medium to long-term future, do you think there are any lessons that Japan can learn from this earthquake as to perhaps better prepare or change the way they see these sorts of things?

James - I think the Japanese are constantly learning lessons from these events, which is why they get better and better. They're not complacent. I mean these things are a tragedy. This one is a tragedy and a lot of people have died. A lot of destruction. It'll cost a lot of money. Lots of people's lives will be really messed up by all this. But from a perspective of people far away, as I say, Japan is much admired and respected because this size earthquake, anywhere in the big earthquake belt, which goes from the Mediterranean to China, routinely kills tens of thousands of people. And that is not likely to happen in Japan. And that is a tremendous achievement. And sometimes you lose track of that. I mean, it is really an astonishing thing, that huge earthquake in 2011 on the east coast, which was a hundred times bigger than this one. The earthquake itself did very little. It was the tsunami, which is a slightly separate story, coming later which drowned 20,000 people and knocked out the nuclear power station. But the infrastructure was really not that much damaged by the earthquake itself, which is a fantastic achievement.

13:36 - AI chatbots found to endorse terrorism

AI chatbots found to endorse terrorism

Gareth Mott, RUSI

The UK’s independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Jonathan Hall, has said that new laws are needed to combat AI chatbots that could radicalise users. Mr Hall told the Telegraph that the UK government’s new Online Safety Act, which passed into law last year, is “unsuited to sophisticated and generative AI”. Gareth Mott is a research fellow in the Cyber team at the Royal United Services Institute think-tank.

Gareth - In most recent articles that have been produced on this on Jonathan's comments, I think he actually a play with some of the examples of chatbot software that we have available, which are based on large language models. The big ones would be ChatGPT and Google Bard and others. And these are systems which process extremely large amounts of data to become a defacto search engine or become a defacto image creation system or become a defacto entity to talk to. And the idea is it gives you the information that you're looking for. There's a philosophy behind the software. It's really just trying to tell you what you want to hear within certain constraints and certain parameters. My understanding is that Jonathan played with an example of one of these chatbots and found that there was a possibility, in fact I think he found that it could, pretend to be a radicalising force, for example an Islamic state affiliate. And obviously the concern there is that given the recent prominence in recent years of, for example, lone actor terrorism, this is another tool that someone might use to kind of self radicalised and become extremist or terroristic.

Will - These large language models and chatbots take their information from absorbing huge amounts of data on the internet. So I guess the question is, do we know where all of this stuff that is causing them to spout potentially radical information is coming from? Is it someone on the internet posting huge amounts of radicalised data in the hope that a chat bot will pick it up?

Gareth - Partly yes. And it's worth pointing out that when you use these platforms, some of them you can use a paid service and ostensibly on paper avoid your data being fed into future systems. But generally, the data, whatever that may be, you feed into these systems, if it's a question, a query, an argument. Data that you feed into the system are then used to improve and build further versions of these large language models. It is providing us information that it thinks that we want, and in part that is fed by previous information that people have been feeding into it, as well as wider secondary sources available on the internet that is continually trawling and gathering in order to analyse. With the large language models, it's worth pointing out that they have guardrails in place, especially the mainstream large language modules that we speak about. And these guardrails are in place to basically ensure that, for example, if I was an extremist and I was asking it to help me write something that was very incendiary to a particular ethnic minority, it shouldn't do that. It shouldn't be able to undertake that command. It shouldn't know that that command is offensive. Of course, philosophically, it doesn't itself know that the command is offensive, but it's been programmed to understand that that command shouldn't be carried out. And so those guardrails should stop it from assisting me to create a bomb or identifying the ideal escape route from a terrorist atrocity that I might be planning to commit. But of course, ostensibly, there are ways to get around that. If you very carefully tailor commands. There are instances where you might be able to overcome the guardrails. At RUSI, We recently hosted a talk by the director of the NCA. He suggested we'ew now seeing instances of sexual predators using artificial intelligence to create artificial images of child abuse. Which is obviously horrendous, right? That's a horrendous activity. But ostensibly that is breaching the guardrails that are in place in these systems. The guardrails should make it harder, or ideally impossible, for people to misuse these technologies. But generally speaking, there will be often with these kinds of technologies, they are dual use and there will be actors out there who will try to find a way of breaching the guardrails.

Will - The concern seems to be as well that this is incredibly difficult because it's so decentralised, that information is coming from so many places, it's incredibly difficult to identify individuals to prosecute. Because if you radicalise someone, certainly in the UK, and they commit an act of terror, you get prosecuted for that. So who could possibly be blamed in the instance that a chatbot radicalises someone?

Gareth - That's a really good question. I was watching the Christmas lecture series by the Royal Institution. These large language models form galaxies of data, they termed it, but it doesn't know what the data actually means necessarily. It's just working out its own way to categorise data so that it can give the users what it thinks the users are wanting to hear. Even though it doesn't understand the data, it is making sense of the data in its own way. The system itself is just trying to give the user what it wants. If the user really pushes it and keeps pushing it to give it content that would help them self radicalise, harden their views and harden their perspectives. If they're determined enough, they'll probably find a way to make the system do that. I would suggest that it tells us more about the individual requesting that data than it does about the system itself. If the large language model didn't exist, that individual might try and find alternative sources elsewhere. In the same sense that individuals are able to radicalise themselves before social networks were widely available. Individuals could still self radicalise through literature, through pamphlets, through discussions with peers. So perhaps we have now ansation, but it isn't necessarily revolutionary. I suspect it won't be widely adopted as a radicalising form, but it's another possibility. And of course we have seen instances in the news where there's been suggestions that people have used this to self radicalise. So it is happening. But who do we focus on in terms of the criminality of this? I would suggest that it is more apt to focus on the user requesting information from the system rather than necessarily the system itself.

Will - Ultimately technology, all of technology, is a tool and dependent on how you wield it.

Gareth - Yeah, exactly.

19:36 - How changing scenery changed our ancestor's language

How changing scenery changed our ancestor's language

Charlotte Gannon, University of Warwick

Scientists from the Universities of Warwick and Durham say they have discovered how a shift in our ancestors' habitat may have prompted early humans to change their vocalisations and ensuing language. Charlotte Gannon is a language psychologist and lead author on the paper.

Charlotte - 17 million years ago, we started to have this big continental tectonic movement. So our geographical landscape completely changed. We moved from living in this dense forests-like world to much more open landscapes. And as a result of all these climate changes, we then started to have all of these different evolutions within our hominid line. So we were really interested in looking at that period when we came down from the trees and started living in these more open landscapes.

Will - So how do you take the tools and things that we have nowadays and turn back the clock and try and recreate something that was going on millions of years ago?

Charlotte - So we use two vocalisations that orangutans make. So orangutans are really important. They're the only arboreal great ape. They're still spending the majority of their time up in the trees. They also make many different vocalisations, but two in particular that we were really interested in were called the kiss squeak and the grumph. So kiss squeaks are what we refer to as consonant-like calls, and grumphs we refer to them as vowel-like calls. So when we make a consonant-like noise, so say a P or a B or a T, we are manipulating the tongue and the mouth and the jaw. And when we make an A-E-I-O-U, we are not using any of that manipulation. We're just making the sounds. And when an orangutan makes a kiss squeak, they follow a very similar pattern of mouth manipulation that we do when we make the consonants. And when they make the grump, again, like the vowels, there is none of this manipulation.

Charlotte - So we're able to kind of use them almost a bit like really early consonant and vowel-like sounds. So we were able to take recordings that we'd had previously and we were able to play these across the Savannah in South Africa.

Will - And what did you find when you played these vocalisations out?

Charlotte - We found that the consonants actually travelled much further than the vowels, which was really interesting. So the kiss squeak noise that the orangutans were making were still about 80% audible at 400 metres, whereas the vowel-like or the grumph calls, they were actually dropping off around 125 metres.

Will - I guess this is a question more acoustics than psychology, but do we have any idea why that might be?

Charlotte - Interestingly, we initially expected the opposite. So the kiss squeak calls are a higher frequency, and the grumph light calls are a low frequency. We would actually expect, from what we know about our frequencies and our law of sound propagation, that the lower frequency sound should have travelled a lot further. And really interestingly, I think it does highlight the importance of actually using the living great apes that we've got. Because if we ran this through a simulator, we would've actually expected the opposite. And what we're looking at could actually be more of an indication as to what happened to our early ancestors and maybe also how differently our vocalisations will have been back in the day.

Will - The idea then is that we shifted to a more consonant dominated vocalisations because it allowed us to communicate better and over further distances. What kind of advantages do you think that would've brought?

Charlotte - If you look upon, not just how far the actual vocalisations you're travelling, but that's how far the message will have been travelling. So if we could have been relying on these consonant light noises to travel much further, then the information was travelling further. It will have helped our social bonding, it will have helped our cognition, it will have helped strengthen our society and helped move our evolution further.

Will - The more I read about it, the more that this seems like because language is so fundamental to our cognitive development, that this could be one of the most important shifts towards us becoming the species we are today.

Charlotte - Language in particular is really hard to study because it doesn't fossilise. We can always carbon date anything we find, but language is just this great big mystery. We know we have it, and we know we're the only animal in the entire world that has it in such a way that we do. A lot of different areas of research will come back to language. You can look at child development, you can look at psychiatry, everything. A lot of it can always be linked back to language, language therapy, all of these things. And yet there's still this big great mystery around language. And I think if we really want to fill in the big jigsaw puzzle as it was about our story language is one of the really important pieces.

24:50 - Could we capture and recycle space junk?

Could we capture and recycle space junk?

Thanks to David Whitehouse for the answer!

David - There have been various initiatives over the years to prevent people from causing more junk. But in the last six months or so, it's now written in law in the United States that you have to have a means for removing your satellite when it's at the end of its life from a useful orbit and put it somewhere where it won't be a problem, preferably burn it up in the Earth's atmosphere. This used to be a convention that you did this, now it's coming into law and the first fine by the American government took place just a couple of months ago. So there are things moving in that direction, and there's a growing international cooperation that this is something that in the past was left voluntarily and has to be done legally now.

Will - So is there anything we can do about the space junk that's already up there?

David - If a satellite fails catastrophically, then there's nothing you can do. It's just stuck in that orbit. There are a couple of companies in the world who are working on smaller satellites, which will go up to an errant satellite, grab it, and then possibly bring it back down to earth so it burns up or push it into an orbit where it's not a problem. But you're never going to be able to do that for many satellites. Most of it we're going to have to tackle with just not causing any more and waiting for the stuff up there to decay naturally, which is going to take decades. There is no way of gathering, in any significant bulk or numbers, the junk that is up there and using it for something else. Space is just too big, junk is too numerous, and you'd use up so much fuel to go from one part to another to collect this stuff and collect small stuff along the way. Nobody's going to do that. It's just too expensive and too difficult.

Comments

Add a comment