Menstrual Science: periods, pills, poverty

This week - we’re pondering periods. With about 800 million people menstruating each day around the globe, we’re re-visiting the biology, musing over menstruation and mental wellbeing, and asking why, in 2020, period poverty is such a problem. Plus in the news - Lockdown, or let rip? Are our efforts to try to stop the spread of coronavirus taking us in the wrong direction? An update on England and Wales’ NHS Covid app. And with England’s ban on some single use plastics now in force, why do we have so much of it in the first place?

In this episode

01:16 - Is there a lockdown alternative?

Is there a lockdown alternative?

Raj Bhopal, Edinburgh University

Among the Covid news this week - US president Donald Trump announced that he and the First Lady are now self-isolating with the virus, and SNP MP Margaret Ferrier has been suspended from the party after travelling to Westminster despite experiencing Covid symptoms. But one of the most frequently asked questions across the media this week was “will we see another lockdown?” The government have described this as their “nuclear option” of last resort. Nevertheless, some are eager that we do go down that route to halt the spread of the coronavirus infection until we have a vaccine. The present strategy, though, is one of stricter local restrictions where there are hotspots and generalised control measures across the country. But, increasingly, as stories have been published of students spending their fresher’s weeks locked in their halls, the possible cancellation of Christmas, and the devastating impact on the arts, other voices are saying that we’re already going too far and that the present approach - to try to suppress the virus - is the wrong one. They’re arguing that it’s not going away; the prospect of a vaccine is too distant and too uncertain, and instead we need to learn to live with it. Chris Smith spoke to Raj Bhopal from Edinburgh University...

Raj - My name is Raj Bhopal. I'm emeritus professor of public health in the Usher Institute, at the University of Edinburgh. We've been hit by a very big pandemic that we've managed to control reasonably well. Considering the formidable challenges. We were slow to start, but once started, we have managed to control things, but we have a very long way ahead, and we cannot continue with the strict lockdowns and strict restrictions that we've seen over the last six months. We will have to change direction.

Chris - Why do you say that? Because if one looks at the numbers, you could say, well, look, the lockdowns in every country that's implemented one, have been incredibly successful. They brought the virus count from what would have been hundreds of thousands of cases a day to near zero.

Raj - I think it's absolutely amazing what's been achieved, but the cost has been very high. The financial costs, the restrictions on freedoms, the damage, not just to the economy, but to health services, care services, very important sectors of our lives. Theatre, cinema, sport, have been seriously damaged. We cannot live with it much longer. The public is voting with its feet. So we've done well, but we need to change direction. We can't keep on going in this direction forever.

Chris - And what direction are you advocating that we should consider pursuing instead?

Raj - Like everyone else I'm desperate for a vaccine. If we get a vaccine, I will be in the queue. Vaccines are not there to be discovered. They have to be invented. That takes a lot of work. Three vaccines I've examined that have been published in the Lancet. The side effects are very common symptoms that mimic COVID-19. Then we still don't know about the long term safety in terms of serious problems. And we don't know the effectiveness. By the time we understand all this, it is going to be a long time. Yes, we may well get vaccines that we can begin to use in spring, but their long term effectiveness, long term safety will not be clear for a very long time. If we get a vaccine that will be a game changer, but the game will change over a period of about two or three years.

Chris - So what is the alternative?

Raj - We learn to live with the virus, whereby we decide that we're going to minimise the damage while we keep our societies as open and functioning as possible. We have to remember that the single most important determinant of health is income and wealth. If we don't have income and wealth, our health will very quickly be damaged, and our health services will crumble. So it's not a case of health or wealth. It's a case of balancing these two things. So the alternative is that we change strategy, clamping down on whole populations is not really working, and it's not necessary. The one bit of good news I can bring is that this disease under 18 is much less severe than flu. After 25, it becomes a bit more severe than flu, but it's over 70 when the problems really start. But even then people over 80, 90% or more will survive. It's not a death sentence, as some people think.

Chris - What would you advocate then? Are you advocating for, almost where it feels like the UK government was sort of heading originally, before they then went down the full lockdown route, which was a sort of managed population immunity approach, where there's a slow trickle of the virus seeping through society. And leaving in its wake immunity. And that translates into a way of controlling the virus for the many in the long term, but it's much less painful economically, psychologically, and educationally than locking down a country, putting everyone on hold until we have a vaccine which might never materialise, let's face it.

Raj - That's exactly what I'm advocating. But I'm not advocating it in a, let the virus rip, or pay no attention to some people. Let's start with young people. They need to socialise. They need education, and they need freedom. They need to develop themselves. It's a huge need and they are hardly harmed by this COVID-19. So we must let them get on with their lives. If some of them don't want to take the risk of getting infections, we would have to respect that. But in their day to day lives, as we're already seeing, it's a high likelihood they're going to get it, even before a vaccine is available. Currently, people are not talking about that. We must start talking about that.

Chris - Raj, on the one hand, I can see what you're saying, but how do you propose to protect the people who are vulnerable so that we can allow this seepage of virus through the younger age groups who are at low risk, without taking risks for the older people? Because that's at the end of the day, why the government has implemented, they say, the present stringent measures.

Raj - Nothing in our society, or any society, is a blanket policy for everyone. Every policy is tailored. We don't give breast cancer screening to men. We don't give influenza vaccines to everyone. Everything is tailored according to need. And we have more than 12,000 deaths every week in the UK, they occur from diseases that are sometimes a lot easier to prevent and treat than COVID-19. But we live with them. Some level of death and disability is going to have to be accepted. Otherwise we will destroy our society.

Chris - Why do you think then, Raj, that the approach that's being taken, is being taken?

Raj - Well, I think there is a great deal of guilt. We were slow to start. We didn't do a good job on the care homes, but also at the moment there isn't a proper, honest dialogue. There's no one brave enough to tell the truth, but we have produced data on 137 million children in nine countries. And we can see what is really happening. The policy has been to petrify, in the hope that people will be so scared, they will follow all guidelines. We didn't use punishments to handle the AIDS pandemic, which is still with us, 32 million deaths, over 600,000 deaths last year across the world. We've had to learn to live with these things.

09:29 - Covid appdate

Covid appdate

Vanessa Teague, Australian National University

The England and Wales NHS test and trace app has been - finally - released! This public health tool, designed to assist with coronavirus contact tracing, has been much-touted by politicians but suffered a number of issues during the launch, including problems with QR code scanning at venues, and no way to register a positive COVID test if you got tested at a hospital. The app was originally very similar to Australia’s version, called COVIDSafe, but switched during development to a different model created by Apple and Google; and so it’s useful to compare the two to see what works and what doesn’t. COVIDSafe launched in Australia back in April, and Phil Sansom asked cryptographer Vanessa Teague: how successful has it been?

Vanessa - We're not quite sure. And that's part of the trouble. The federal government, for some reason, refuses to cough up any data at all. We don't know how many people are actually using it. And we don't know what fraction of contacts that it is successfully detecting. They must have that information, right? Because the app interacts actively with an Amazon server at least once a day. So they could easily be telling us, but they've chosen not to.

Phil - Right. So I'm guessing, we're not saying that no news is good news here?

Vanessa - Indeed. One assumes that if 99% of people who had downloaded were still using it, they would probably find it in their hearts to share that information with us.

Phil - Now, can you just explain how different is it to this NHS app that's just been released?

Vanessa - Right. It's actually very, very similar to the earlier British app. COVIDSafe runs a centralised protocol. In other words, the Bluetooth messages that you're sending around, are encrypted versions of your ID. And when you test positive, you upload to the authorities, a list of the encrypted IDs of all the people you've come close to, and they decrypt the ID and notify the person. The information flow is exactly the opposite way round from the decentralised Apple-Google framework, which Britain and most other countries are now using. In the decentralised exposure notification framework, you're doing on your own phone, a computation that tells you whether or not you've come into contact with anybody who has just tested positive for the infection. There's never a need for a centralised authority to learn who's been in contact with whom.

Phil - It's been quite a crucial question, hasn't it? Because the NHS app switched from the centralised to the decentralised. Why is that?

Vanessa - Yes. One of the reasons was that centralised vision just kind of didn't work very well, and COVIDSafe didn't work very well either. You know, it drained the battery. It wasn't as effective as people hoped. It crashed, et cetera. Realistically, that's probably why the NHS app switched over. But I think there's a huge advantage to the decentralised version in that it doesn't build up in a centralised database, a list of which infected person has been near whom. Now, the epidemiologists would say, you also don't get the advantages of scientific analysis of a great big centralised database of who's been near whom, when, and who got infected how, but I'm concerned, at least in the Australian case, about the possibility that that highly sensitive database might potentially be misused, or potentially might just be leaked.

Phil - What about this other factor, that Apple and Google protected this technology that the apps rely on, which is using Bluetooth at really low power?

Vanessa - Right. So long, long before COVID, advertising companies, specifically Google, but plenty of others as well, realised that you could get a very, very accurate picture of where somebody was, if they were willing to turn on Bluetooth low energy on their phone, and scan for Bluetooth beacons that you could carefully put at special locations in shopping malls, or train stations, or something. And so Apple in particular, controlled access to these functions as a privacy feature. Then when COVID came along, somebody had the brilliant idea of using Bluetooth based tracking for connection recording, then Apple and Google had to think of something to do about it. So they responded to this situation by creating this very specific decentralised protocol, rather than just declaring open slather.

Phil - Right. So what you're saying then, is that Australia have essentially stuck to their guns, and they're struggling to get around these privacy restrictions on phones that don't let you use low power Bluetooth easily.

Vanessa - Yeah, that's exactly right. The only slight additional complexity there, is the Australian app initially had a lot of bugs that interfered with the basic workings of the thing. And they blamed Apple for a lot of them, which in fact were just coding bugs in their app.

Phil - Okay. Taking it altogether then who do you think has made the right decision?

Vanessa - Oh, I definitely think Britain has made the right decision. In Australia, we never really had the opportunity to have a real discussion or democratic decision about it. We still have never really got a clear answer on whether the Commonwealth authorities have access to the data, or whether it's only the state authorities, which is actually a big deal in Australia for various reasons. The fact that it was fairly openly and democratically done in the UK, led directly to a good decision to switch.

15:59 - England bans plastic straws

England bans plastic straws

Taylor Uekert, Cambridge University

On Thursday 1st October, the government announced that plastic straws, stirrers and plastic-stemmed cotton buds are now banned in England. This is welcome news for many with concerns over single-use plastic and its wide-ranging environmental impacts, with England using an estimated 4.7 billion plastic straws, 316 million plastic stirrers and 1.8 billion plastic-stemmed cotton buds each year. So how much difference will this make? And how can science help our society to use plastic more sustainably? Taylor Uekert is a plastics expert and member of the CirPlas (circular plastics) research group at Cambridge University, and Adam Murphy and Katie Haylor asked her about the ban...

Taylor - So it's definitely a great first step. The thing about a lot of these plastics is: a) they can't be recycled because they're too small, so they fall through the sorting equipment, and often it's just not economically viable to recycle them; and b) when they do leak into the environment, they can cause a huge amount of problems for wildlife and the oceans. Because they're so small, they break down easily; they're brightly coloured, they look like food, and so a lot of creatures will end up eating them and that causes problems later. So it's a really good first step in terms of getting us to think about what single use plastics are necessary and which ones aren't, and how we can cut them out of our lives. But it's still just a first step. Overall these straws and stirrers probably account for less than 0.1% of marine plastic pollution. So there's still a long way to go in terms of addressing this huge issue.

Adam - But what about for people who can't drink without a plastic straw? Are there any accommodations being made for those people?

Taylor - Yes, definitely. So people with disabilities or other medical reasons for needing a plastic straw to drink - they will still be able to access these materials.

Adam - How come now, in 2020, with everything that's going on, why is so much plastic not getting reused or recycled?

Taylor - So there's a few reasons behind that. One is that we just have a huge diversity of plastics. So when you look at all of the things in your recycling bin, you might actually see that they all have different labels, and each of those different types of plastic has to be recycled separately. And this is not always straightforward in terms of separating them out and then recycling them. So that's the first issue. And the second issue is just that single use plastics are still just really convenient; especially now with coronavirus they're essential in many cases. And so replacing them with a more sustainable reuse or refill model does take commitment, and it's something we haven't quite managed to do yet.

Katie - In addition to just using less, your group are exploring a few different avenues; what particular solution have you been working on?

Taylor - What I work on is a sunlight driven method for turning plastic waste into hydrogen fuel. The cool thing about this is it's really simple, you only need four components: plastic, water, sunlight, and a photocatalyst, which is just a material that uses the energy in sunlight to make a chemical reaction happen faster. So you combine all of these different ingredients and the photocatalyst ends up breaking down your plastic and water, and releasing hydrogen which we could potentially use as a green fuel.

Katie - What's the yield, or how long does it take to do?

Taylor - It's still a very slow process. We're at the beginning of this research. It probably takes about a month to break down half of the plastic, but it's something we're really working on and trying to push that further.

Katie - Are you hopeful that you'll be able to scale it up in terms of time efficiency and how much you get out of it?

Taylor - Yes, definitely. We've done some initial experiments going from these small pieces of plastic, like two centimetres, up to something 50 times larger; and we're hoping to go further and build a rooftop demonstrator to show this is feasible on a larger scale.

20:22 - Mailbox - artificial sand in Manila Bay

Mailbox - artificial sand in Manila Bay

This is the section of the show where we address your correspondence. Razel is from the Philippines, and is asking about some news about the “white sand of controversy” in Manila Bay - where an artificial beach project using dolomite rocks has been criticised for being an environmental hazard. He asks: “what is the science around Dolomite sand, and does it have health related risks?”

Adam - Well our very own Phil Sansom has been looking into this, and he explained that dolomite is a naturally-occurring type of rock that’s closely related to limestone - it’s a sort of calcium-magnesium carbonate. In this case it’s coming from a large dolomite quarry on a southern Philippine island, and since August has been travelling on ships in crushed form up to Manila.

This is part of a rehabilitation programme to clean up the notoriously polluted bay - or at least, clean up its image. But the Philippines Department of Health have warned of respiratory risks if you inhale aerosolized dolomite dust, and as Bored Chemist pointed out on our forum, people and the waves will probably crush the rocks down to dust over time. Others warn of damage to the bay ecosystem from heavy metals leeching into the water.

There’s limited evidence around dolomite dust’s health or environmental risks in particular, but perhaps this is a relevant point and worth exploring before continuing the project. We’ll be following this story and hoping for some more concrete research soon.

22:13 - What actually is a period?

What actually is a period?

Caroline Overton, Royal Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

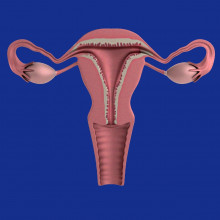

It’s October, and now that kids are back at school here in the UK, perhaps it’s time to consider some conversations other than covid that might be taking place in the corridors, classrooms and bathrooms. This year in England the government announced it was making period products freely available for schools to order in, for kids that need them. And according to period.org, the 10th October marks national period day in the US. So this week we are pondering periods. How does the menstrual cycle work, and change throughout life? When should you seek help if you’re worried about your periods? And how can we improve access to not just period products, but period education too? First though, what actually is a period? Close to half the global population have them each month - but how confident are you of the basics? Consultant gynaecologist Caroline Overton is with us to get us all up to speed. But first, here are Eva Higginbotham and Phil Sansom with a quick fire science...

Eva- If you have ovaries and are between the ages of about 12 and about 50, chances are that roughly each month you’ll experience a period - a bleed from the vagina. It’s not dangerous, or gross. It’s biology.

Phil - Periods are unique to the person having them, but on average, they tend to start at around 12 years of age and will last somewhere around 5 days each time.

Eva - Say a typical menstrual cycle is 28 days long. Day 1 is the first bleeding day, and by day 5 or so the bleeding will have probably stopped. A few weeks later, day 14 or so, the brain will release chemical messengers - called hormones - into the bloodstream that tell the ovaries to release an egg into the adjoining fallopian tube. Then the ovaries release hormones to thicken the lining of the uterus (sometimes called the womb), in case the released egg meets a sperm on it’s way down the fallopian tube and gets fertilised.

Phil - The egg - fertilised or not - then moves into the now thickly lined uterus. And if it’s not been fertilised, it breaks down.

Eva - Ovarian hormone production drops, and the uterus lining also breaks down, and it’s the broken down lining that comes out of your vagina for a few days that is your period.

Katie - Caroline, which hormones were Eva and Phil talking about there?

Caroline - Oestrogen and progesterone, produced by the ovaries and controlled by the pituitary gland.

Katie - So those are the main hormones we're talking about when we're thinking about the cycle, is that right?

Caroline - Those are the main hormones.

Katie - When we talk about blood loss - and we'll talk about pain in a little bit as well - is it possible to quantify how much bleeding we're talking about, and how much pain people might experience? Is there a typical amount?

Caroline - So a typical amount of blood shouldn't make you an anaemic. You shouldn't be passing big clots; you might pass tiny clots, but you shouldn't pass clots bigger than a 50p. And essentially you should be able to carry out your work, school, normal activities, without needing to stay at home. In terms of pain, you might need to take a household painkiller such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, but it would be abnormal to regularly miss work, school, or activities because of period pain.

Katie - So we heard there, around the ages of between about 12 and 50 is when people would tend to menstruate. People who have ovaries are born with potentially millions of eggs in the ovaries, is that right? So why do we actually stop menstruating?

Caroline - We don't know exactly why people stop menstruating. We know that there are still eggs present in the ovaries, so there is some sort of signal for the periods to cease; exactly why, we don't know.

Adam - When that actually happens, it's called the menopause. So what actually goes on then during that, in the body?

Caroline - Menopause just means "end of periods". Actually, what happens... there are greater changes happening in what we call the perimenopause, the run up to your periods stopping. And there, your periods - which might've been regular and monthly - start to first of all get closer together, so they're coming around maybe twice in a month; and then they will tend to space out, you'll start to miss periods, and you might also start to get the symptoms of low oestrogen of which hot flashes and night sweats are the classic ones.

Adam - We associate periods with fertility. So what happens if that menopause happens much earlier than expected?

Caroline - So you're quite right that some women can have an early menopause before the age of 40. It is commoner in some families, so it's worth asking if your mother had an early menopause; sometimes it's the result of surgical or hormonal or chemical treatments, for example for cancer.

Adam - What should women do if they run into these problems?

Caroline - I think the main thing is to be aware that your periods are a sort of marker of your hormonal wellbeing; you should have them roughly monthly, and if your periods have suddenly changed to stop, then there's something not quite right. Women shouldn't feel embarrassed to go along and talk to their GP and say that their periods have changed.

Adam - How serious would it be, or is it just something that just needs to be dealt with?

Caroline - It would all depend on the stage of life. Early menopause is going to be very serious if somebody is still planning to have a family, but mostly people with ovaries will have spacing out periods due to hormone imbalances like PCOS, which I think we're going to discuss later. And all of this is amenable to treatment.

28:02 - Menstruation and mental wellbeing

Menstruation and mental wellbeing

Hannah Short, GP and women's health doctor

To discuss the relationships between the menstrual cycle and mental health, GP and women's health specialist Hannah Short spoke to Adam Murphy and Katie Haylor. Firstly, Katie asked whether the cessation of periods (the menopause) can have an impact on how someone might feel...

Hannah - Yeah, they certainly can. I think there's two main aspects. The emotional and psychological impact of changing hormones in itself can have an effect because the changing levels affect your brain and so it can lead to symptoms like mood swings and insomnia, anxiety, loss of confidence and irritability. But then there's also the psychological side of it directly by the fact you've stopped your periods. Some women will mourn their loss of fertility or they see it as a sign that they've now passed their youth. And obviously that's particularly problematic for women or girls who have gone through a very early menopause or lost their ovaries as a result of surgery.

Katie - In general, how well do scientists understand the relationship between your mental wellbeing and your menstrual cycle?

Hannah - There's a general appreciation that there is a connection, but to be honest, I don't think it's understood well enough or the severity that can occur is not really fully understood or recognised. I mean, the Royal college of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists have guidelines for PMS, which is premenstrual syndrome. And that's where women will struggle with symptoms in the two weeks leading up to their period. There's a recognition that there's some degree of severity. So for some women it will just be mild unpleasant symptoms and others will be really quite severe. Not everybody's aware of these guidelines. So I think the scientific and medical community needs to do a lot more kind of work around it, but I think it is gaining recognition and understanding.

Katie - Is there a sort of a correlation that we can appreciate between hormonal variation and moods specifically?

Hannah - There's no such thing as typical, I suppose, but often people will associate the first part of the menstrual period - so just the day that your period starts and for the first two weeks of oestrogen rising - their mood tends to improve, their energy tends to be better. Libido is often increased around ovulation. Then the second part of the cycle, when the oestrogen is dropping and the progesterone is rising, a lot of women might feel a bit more irritable, may feel more tearful. Again, this, as I was saying, the severity of that really varies. In about one in 20 women will struggle with very, very severe symptoms. They say it's almost like a switch has been flipped and they're a different person in the second part. And that's when you have something called premenstrual dysphoric disorder or PMDD.

Adam - And, what would you do to advise people to seek help with how they're feeling and what kind of problems can arise for them?

Hannah - Well, I was just saying about the PMDD for the 1 in 20 women, or those who are born female who still have their ovaries, it can be really quite debilitating the symptoms. So they can have suicidal thoughts, it's not just feeling a little bit low. Very severe anxiety. If that's happening, that's obviously not normal and needs help and recognition. Going to see your GP would be the first port of call and keeping a track of your symptoms to kind of show that there's a cyclical kind of nature and that you're not feeling like that all the time. There isn't like an underlying psychiatric diagnosis there.

Katie - What can be done to help? Are there medications that would be appropriate? How do you help as a doctor?

Hannah - It depends on the severity. So women who are having milder symptoms, lifestyle changes like regular exercise, sleep, eating a fibre rich diet can help. Vitamin B6 and magnesium supplements - there's some evidence for those. With people with the more severe symptoms, where they're having to miss school or work or it's affecting their relationships, then things like the SSRI antidepressants can help stabilise the brain and reduce those mood side effects. And things like the contraceptive pill, or HRT can help as well. In some severe cases, having an induced medical menopause - so you have injections to switch off the ovaries - can help. And you're given some HRT to help protect your bones and things like that. And in very severe cases, some women have their ovaries removed, but that's at the very extreme end.

Katie - The menstrual cycle and wellbeing isn't a subject that is talked about loads. As a woman's health doctor, how would you summarise the societal perception of menstruation and mood?

Hannah - I think it's probably still viewed as quite a taboo, I think. Because you've got two kinds of taboos there anyway. I mean, hopefully things are changing, but historically menstruation and mental health are things that people steer away from so when you get that combination I think there's quite a reluctance to talk about it. Unfairly women have often been viewed as quite hysterical, it's probably where the word comes from - stereo and hysterectomy when you're talking about removal of the womb. I think things are getting better, but because it's not fully understood, I don't think women are often believed when people say that their menstruation is really affecting their mental wellbeing. And I'm hopeful that will change as the conversation opens up around it. There's the lack of acceptance really on the societal level, that our moods do change - it's a normal part often of being female. I mean, obviously if it's affecting your day to day life in a very difficult way, that's different. But I think that there's definitely room for society to kind of embrace the fact that women are generally cyclical creatures and not going to feel the same from one day to the next and that's not how we've evolved to be.

33:41 - Not everyone has an average period

Not everyone has an average period

Caroline Overton, Royal Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Not everyone has the average period described in the quick fire science earlier. In this section, we hear a tough personal account of endometriosis, and discuss the science of endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome with gynaecologist Caroline Overton...

Sophia - Before experiencing endometriosis, I didn't know that such pain was possible every month. I would find myself on the floor fluttering in and out of consciousness as an invisible hand seemingly worked to slice my lower abdomen apart with a series of blunt knives. I was so scared. The first doctor I saw told me some people just have painful periods. Fortunately, I didn't listen.

Eva - Endometriosis affects about 10% of people with ovaries worldwide, where cells like those that line the womb, the endometrium, grow where they shouldn't - like on the ovaries or fallopian tubes. These misplaced cells respond to the same cyclical hormonal cues as the endometrial cells in the womb, so with each menstrual cycle, they grow, and then shed. Only because they are outside the womb, they can't leave the body through the vagina and instead can cause irritation and pain. And this in turn can lead to the growth of scar tissue and adhesions between organs.

Sophia - I'm now post-op and things are much better, but there is no cure, only management. And I worry everyday that a resurgence of that immobilising pain, those days of lonely desperation and fear, await me just around the corner.

Katie - That was Sophia there sharing her experience. And you also heard from Eva Higginbotham. Caroline, is it common with endometriosis to experience that level of pain?

Caroline - Well, thank you for sharing Sophia's experiences. I'm very glad that she didn't take the doctor's advice that it was normal. Very much wasn't, and that sort of severe pain where she is in agony is not normal and is classic of endometriosis.

Katie - In Sophia's case, she had surgery, which helped what are the treatment options short and long term with this condition?

Caroline - So the main aim of treatment now would be about picking it up as early as possible so that hopefully you can avoid the long term complications such as adhesions and infertility. So the current guidelines are to actually make the diagnosis based on the symptoms. So somebody like Sophia coming along and saying, I'm doubled up with my period. That should flag up that she might have endometriosis. There are painkillers, there are treatments like the hormonal pill. Basically, you want to make the periods either disappear completely or shorter and much lighter in order to control the endometriosis and the symptoms.

Katie - Are there fertility implications here?

Caroline - There are fertility implications. Endometriosis starts as little pimples in the pelvis, which are slightly sticky as they grow and develop. And those can cause the organs to stick together, which we call adhesions, and the adhesions then can get in the way of the egg escaping from the ovary and/or getting down the fallopian tube, causing infertility in the longer term. What we don't know is why some women get severe adhesions and in other women, it seems to have a much more benign course where it doesn't progress so much.

Katie - What are the theories?

Caroline - There may be a sort of family link there, so an inherited problem - you are more likely to have endometriosis if a family member of yours has got endometriosis and it's more likely to be severe. We think it may be linked with the amount of period, think of that period slightly overwhelming the body's immune system and stirring up the blood cells from inside the pelvis. The other one is that there is an immune modification, that you've got a slightly altered immune response where in some ways those immune cells are not clearing up as well.

Katie - Endometriosis can result in having to manage severely painful periods as we've heard. And managing irregular ones throws a different challenge and one potential reason for this could be a condition called Pcos or PCOS. Time for another quick fire science from Eva.

Eva - Polycystic ovarian syndrome, sometimes called Pcos or PCOS, is a common syndrome whose cause isn't well understood. It's often characterised by its symptoms, which can include the growth of more follicles or egg sacs than is normal on the ovaries. These sacs aren't always able to release the egg inside, which can cause problems with ovulation periods and fertility. People with PCOS can have irregular or no periods at all as a result. And also often have higher than normal testosterone levels, which can lead to symptoms like weight gain, acne, and hair growth on the body in a more typically quote unquote male pattern sometimes with hair growth on the face, chest and back.

Adam - So we've talked about the fertility outlook for people with endometriosis, but what about the fertility outlook for someone diagnosed with this, with PCOS?

Caroline - Somebody diagnosed with PCOS is likely to have irregular periods with long gaps between them. Although some people with PCOS can have regular periods. If you're having long gaps between your periods, you're not ovulating as regularly and there might be a delay in getting pregnant. It's normal to have a period every 25 to 35 days. So if you're getting longer than that, that might be a problem, and you might have Pcos.

Adam - Now the condition is also associated with high insulin levels. So why is that? And what does it mean for someone's health throughout life?

Caroline - Those high insulin levels are part of the changes in the body causing the hormone changes that lead to the effects that we heard about in the snippet there. You get increased production and activity of hormones like testosterone. That high insulin level leads to insulin resistance. So your cells if you like are numbed to the effect of the insulin, and there's a diabetic tendency there.

Adam - How can you manage a condition like this, or what's the best way to go about it?

Caroline - It would be about making a diagnosis. It would be if you are overweight, trying to lose weight, eating a healthy, balanced diet. And if your periods are still very irregular, drugs such as Metformin, which increase insulin sensitivity, and possibly if you're wanting to get pregnant fertility drugs such as clomiphene.

40:49 - Tackling period poverty

Tackling period poverty

Ema Jackson, Plan International

Let’s zoom out from the doctor’s office now, to take a broader societal perspective on menstruation. And “Every month, girls in the UK face period poverty: two fifths have had to use toilet roll because they can’t afford proper sanitary products.” That’s a rather damning quote from the charity Plan International in reference to a recent report they conducted, and global campaigns manager Ema Jackson spoke to Katie Haylor and Adam Murphy...

Ema - The term period poverty refers to the inability to afford or access the products needed to manage your period. And this is an issue that's affecting millions of people all around the world and having a huge impact. It's especially acute in places of extreme poverty, as you might imagine. So places where there's little access to water and sanitation facilities. But like you say, it's also an issue here in the UK too, which people are often quite surprised about, given the fact that we're kind of in one of the richer countries in the world. We did a survey with girls in the UK and we found that many were suffering because they couldn't afford to access the products to manage their periods. So we found that 1 in 10 couldn't afford period products and then 42% - so almost half - of girls were saying that they'd been forced to use makeshift items such as socks or toilet roll because they'd been struggling to afford proper products. And our research showed us that period poverty is quite a complex issue that goes beyond simply this affordability of period products. And it's actually made up of what we're calling a kind of toxic trio of three connected and reinforcing issues. So firstly, the high cost of period products. Secondly, a lack of education about what makes a healthy period. And then thirdly, the deep stigma that still surrounds periods all around the world.

Adam - Given that we are in the middle of a global pandemic, what are the consequences for young people now with this?

Ema - There's huge consequences always to this issue. And then we've seen them kind of increase during this lockdown period. So period poverty has a huge and very real impact on girls’ lives. So a key example of this is on education. We see that girls are embarrassed around kind of leaking, or not having access to products, or being bullied. And so they're missing out on school because of their periods. And this is happening all around the world. So we see that 70% of girls in Malawi - a country in Southern Africa - are missing one to three school days per month due to menstruation, which is more than they miss due to malaria. So it is really significant. And period poverty is also putting girls physical, sexual and mental health at risk. So damaging their self image, their self esteem. Because of this kind of period stigma and lack of education, that's meaning that they don't access doctors in the same way and because they're embarrassed. And so it's causing late diagnoses of serious conditions, such as the ones you've been talking about on the programme. So it's brilliant to kind of be opening up those issues.

But then in lockdown, we've seen this compound, particularly around the issue of access to products. So we found that girls are struggling to afford and access the products that they need. We know that families are facing tough financial choices all around the world right now. And it's meaning that more women than ever are having difficulty accessing the products they need. We surveyed girls and found that 3 in 10 girls since lockdown began, had been having issues, affording the period products that they need, which is sad to hear.

Katie - I was talking to a colleague, Ema, earlier in the week about access to toilets as well, not just period products. How are charities like yours trying to support people at the moment?

Ema - Yeah. So there's a whole range of different things that we are doing. So you spoke about toilets there. So kind of firstly, on the global side, we're doing things like constructing girl-friendly toilets in schools and communities, and access to water and sanitation facilities. And trying to support girls so that they no longer need to use unhygienic materials. Also, when an emergency hits like a natural disaster or also COVID, we're providing essential dignity kits, which include period products because these are often kind of forgotten about in emergency response.

And then in the UK, we're doing lots of different things to raise awareness around period poverty and break down the stigma. It's an issue we've been working on since 2015. We did a big research report called Break the Barriers to get more people understanding this issue and getting people talking about it. And then we've done campaigning to the government to call for change around the education curriculum, around access to products. We even secured a kind of period emoji after girls told us that they felt that this would help them better communicate on this issue. So we're kind of trying to tackle it holistically across those three different areas that I discussed in that toxic trio, the access to products, the education and the stigma.

Adam - You mentioned the stigma there. How pervasive is that period stigma, now, in 2020?

Ema - Unfortunately, it's still really pervasive. So it's been there for centuries. But it's still there now. So whilst periods are a normal bodily function and a universal fact of life wherever you live in the world, sadly the shame and stigma still comes with them. So there's a sense that periods are kind of dirty or disgusting or make women weak. They're shameful, they need to be kept a secret. So we've kind of been indoctrinated to think that a perfectly natural bodily function is kind of abnormal in some way. And because it's predominantly affecting girls and women, it's a gender equality issue really. So we know that one in five girls have experienced teasing and bullying because of their period, and that one in five admitted that they didn't actually know what was happening when they started their period, which shows how much this stigma is still pervasive in 2020, because it's not being talked about enough for girls to understand what's happening when they started their period. And it's an issue globally as well. So 48% of girls in Iran believed in a survey that menstruation was a disease. And then there's extreme examples of this period stigma that are still practiced in 2020. So an example of that would be a practice called chhaupadi in Nepal, in which girls and women on their period are considered impure and unclean. And they're banished from the household and made to live for the duration of their period in makeshift huts, outdoors, which exposes them to lots of health and safety risks. So unfortunately, even though we think maybe there's lots of more progressive thought around lots of different health issues in 2020, this is still a key issue. And it's called a lot the final taboo. And it's definitely still there.

Katie - The thing is, better menstrual education and awareness is just better for everyone, whether you have ovaries or not, it's better for society. So what progress do you think, Ema, is being made in terms of access to education around periods, whether you menstruate or not?

Ema - Yes. We've definitely seen a lot of progress on this issue. So there's been a kind of growing and active periods activism movement in the UK and around the world. And from that we saw calls that Plan International UK and others supported to the government to call for the relationships and sex education curriculum to be amended, which we have seen happen. And so there is now discussion around what a healthy period is on the curriculum. And it will be interesting to see how that new curriculum is rolled out, especially in the post lockdown Covid situation that we're in now, seeing how education is prioritised in different ways.

But as you mentioned, it's really important that everyone learns about periods. I think the idea that it's something that just girls should learn about really reinforces a lot of the stigma and the secrecy and it being it kept as something just for girls. And so it's important that in all areas of life and with all people, we're having education on this topic. So it's not just traditional school things. I think this programme has been a kind of really good example of education and information sharing about this issue that can go out to everyone in society. And everyone in society has a role to play in breaking this stigma down.

Katie - Caroline, I want to bring you back in here because of course not all women have periods. And equally, not everyone who has a period is a woman. So how well do health professionals understand the experiences of menstruation for people who don't necessarily identify as women?

Caroline - So I think that the primary duty of a doctor is to the number one care and safety of their patient. And that should be separate to their beliefs. And just bear in mind that our patients come from very diverse backgrounds and beliefs. So I would like to see doctors just taking an open view, taking the lead from the patient and then dealing with those issues as the patient sees them.

Katie - And Ema, does this relate to the issues around access and stigma that we were talking about earlier?

Ema - Yes, definitely. So I think we need everyone in society to be part of that process of breaking down the stigma. And we need to be really inclusive in the language we use and recognise, as you've said, there are trans-men and non-binary people that are experiencing periods as well as lots of women who, for example, for health reasons or being pregnant or post-menopausal, or being trans-women, are not experiencing periods. And sometimes this is where the stigma can be the deepest. So we definitely need to be inclusive in the language that we use and recognise that this is a complex issue. And that no two period experiences are the same.

Katie - So we've mentioned education, we've mentioned stigma, and cost is still a major factor in this problem. Are we going to see the end of the tampon tax, do you think?

Ema - Yep. So the government has committed to ending the tampon tax. That's the tax that sees period products as a luxury item, so there's a 5% tax on them. And so the government in the spring budget committed to the end of that, which is a big step forward in gender equality. And we should see that being removed from January, 2021. But it's important to recognise that won't go that far in tackling period poverty. It saves about 40 pounds per woman over her lifetime. And so we need to see more action towards ending period poverty, even though that is a forward step.

Katie - Caroline, we started the topic of periods by talking to you about some of the basic biology. And now I want to come to you for the close. Is there anything else that you would like to add?

Caroline - Hannah brought up a very good point about periods and the hormonal changes during the month. 90% of women will get some sort of changes in the run up to a period. So we all recognise a bit of breast tenderness, a bit of bloating. PMS and PMDD are just much worse, and often with severe depression as one of the symptoms. So if I had one key message from today, it would be that your periods should be entirely manageable. And if you are running your life around your periods, then your periods aren't normal.

51:36 - QotW: Do insects have a stress response?

QotW: Do insects have a stress response?

Eva - Thanks to the cooler weather here in the UK, the mosquitoes and flies that like to take up residence in my house each year have finally moved on, but I know one scientist who won’t be celebrating that fact - insect expert Eleanor Drinkwater, who answered Charlie’s question for us.

Eleanor - It's actually been suggested that this fight or flight stress response may have evolved really, really early in animal evolution. In fact, it could have evolved earlier than the split between animals, which have a backbone of vertebrates, and invertebrates, which means that we might expect to see certain similarities in stress responses between vertebrates and invertebrates. So in vertebrates, a signal from the brain in very simple terms, leads to a release of adrenaline, which in turn leads to a range of physiological changes preparing the animal for fight or flight.

Eva - Heart racing, rapid breathing, sweaty palms? All a normal response to stress in humans and caused by adrenaline. But what happens in invertebrates?

Eleanor - Well, first of all, we don't see adrenaline. But we do see other hormones which appear to perform a similar function. So in invertebrates, one of the key hormones for this is a hormone called Oktober mean. Now, this hormone is released in the invertebrate brain, as well into the hemolymph. So hemolymph is essentially an invertebrate equivalent of the bloodstream. So from the human limp, the Oktober mean affect a wide range of tissues, including things like the heart, the airbags, the sensory organs, and on top of this, it also causes a release of stored hormones, which lead to fat reserves being mobilized, allowing the invertebrates to prepare for rapid activity.

Eva - So there are remarkable similarities between how humans and invertebrates prepare their bodies for this fight or flight response. But some invertebrates do have some...creative defensive responses in their arsenal, too!

Eleanor - So one of my favorites, for example, is the small caterpillar. Now when they are alarmed, they will rear up lash with these amazing whips which come out of their tails, as well as even spraying formic acid. And which is just really remarkable, and something that you just wouldn't see in vertebrate systems. So even though you get these certain similarities in the kind of physiological preparation for fight or flight between vertebrates and invertebrates, invertebrates still have a lot of really fascinating and specific tricks up their sleeve.

Eva - Thanks Eleanor! Next week, we’ll be pondering over this question from Jo:

Jo - My question is about drinking water. We drink gallons of the stuff in a lifetime, but which is better for us, hard or soft?

Related Content

- Previous Nudging you to act...

- Next Do insects have a stress response?

Comments

Add a comment