Stripping down STIs

We’re stripping down sexual health and sexually transmitted infections! Coming up, will we soon have a vaccine for chlamydia? And what happens in a sexual health check up? And in the news, the fires in the Amazon rainforest, and a new weapon against malaria...

In this episode

00:57 - Fires in the Amazon

Fires in the Amazon

Rachel Carmenta, Cambridge University

Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, often dubbed “the lungs of the planet” and home to an impressive variety of plants and animals, is on fire. The scale of the damage isn’t known yet. So why has this happened, and what might be the consequences? Izzie Clarke spoke with Rachel Carmenta, from the University of Cambridge Conservation Institute...

Rachel - In its natural state the rainforests wouldn't burn. They're very moist places, they're steeped in shade, there are ferns and there's a lot of water in the system. But what's happened over time is that rainforests have become more fragmented and they've been logged and so that means that certain trees, the large valuable timber trees, have been taken out. When that happens, big openings in the forest appear which means that sunlight can penetrate through, which means that all of that tinder and all of the vegetation can be dried out and then it becomes fuel for fire. And then you combine that with many more actors in the region using fire, combined with the climatic factors of drought and changing temperatures. It has created a situation in which once fire resistant rainforests are now fire prone.

Izzie - You mentioned that people sometimes use fire in the Amazon. So why would they use fire in that case and how is this year different from that?

Rachel - For many many years and generations, traditional small scale landholders including indigenous communities, they use fire. It's absolutely essential because that's how they clear the land to grow their crops. But they do so with different management practices to contain a fire. And so this is why for all the generations in which fire has been used we haven't always seen these uncontrolled fires in forest landscapes. But today we have begun to see, and not just this year but since really the 1990s, fires and mega fire events recurring throughout these landscapes because of other types of land uses which have come to the region, such as soy and cattle production and other different types of agriculture and including industrial scale agriculture, which has created a very different situation where fires are now prevalent.

Izzie - What is the impact of these fires at the moment?

Rachel - A lot of the discourse that talks about the problem of fire focuses on the environmental burden. So for example the climate and carbon related emissions, or the biodiversity impacts which are relevant to the global community and of course really do matter. But what is missing perhaps is thinking about the local and the lived experience of suffering those wildfires Those households that are feeding their own families, growing their own food, hunting when they need to, fishing when they need to, and when fires come through they lose their agricultural plots, they lose the ability to hunt because the animals have made themselves scarce or been caught in the blaze, but also because hunting is more difficult when the forest is burnt because of all of the crackle and the crunch underfoot. So you can no longer have silent passage through those forests.

Izzie - Is there any way that forests can recover from damage like this?

Rachel - More so when the fires have passed through the first time, I think the cycle gets harder to break the more that the fires recur because the forest gets more and more impacted from those events to the extent where some scientists talk about tipping points in the Amazon, which are a real concern for the global climate, for biodiversity.

Izzie - Are we seeing more uncontrolled fires around the world?

Rachel - Yes, we are, and that's predicted to increase into the future because of extending fire weather seasons. The Indonesian peat lands for example have suffered catastrophic fires, 2015 was declared a humanitarian crisis, Bolivia is also having problems with uncontrolled fires and it's predicted to worsen if something doesn't change.

Being glass half full

Olivia Remes, Cambridge University

A paper published in the journal PNAS suggests those of us with an optimistic outlook live longer! To put this idea under the metaphorical microscope, Cambridge University mental health researcher Olivia Remes, who wasn’t involved in the study, spoke to Chris Smith...

Olivia - They looked at two cohorts, one was about 70,000 women and 1,500 men, and they followed up the women for ten years, the men for 30 years. They measured various confounders and they found that optimism leads to longer life.

Chris - How did they establish that someone was an optimist?

Olivia - They used self reported questionnaires such as: “Do you tend to see the brighter things in life?” “Do you get upset easier or not?” “Do you handle stress well?”

Chris - And the outcome measure was just whether or not someone lived longer or not?

Olivia - So they looked at mortality.

Chris - And what did they actually find, what were the raw numbers?

Olivia - They found that people who were more optimistic had, in general, a longer lifespan, but it wasn't just that, they also found that the most optimistic people were almost twice as likely to live to age 85 and beyond than the least optimistic people.

Chris - Did they look at ill health as well? Were these people, they were living for ages, but they also were living with all kinds of disability and disease or did they remain overall healthier? Did they have a longer healthspan as well as longer lifespan?

Olivia - Of course, they took various confounders into account, like chronic diseases, cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. They also looked at socio-demographics, or their age, marital status, but also their health behaviors because this influences your life and survival.

Chris - Big numbers aren't they? I mean not just the size of the cohort they looked at, which argues this is probably a very robust study, but the effect, the scale of the effect, is very large in terms of if you're an optimist you live a lot longer. Why is that?

Olivia - There are various factors that come into play. One is your immunity. It actually enhances your immunity, but also you are able to cope with stresses in life better and you have a tendency to reframe situations. So, instead of seeing something as a threat, you will see it as a challenge instead.

Chris - Do you not think though, that if you live in a particularly nice environment and you're used to things going your way, you're more likely to be an optimist, as a consequence of that environment? And if you live in a pretty awful environment and things don't go your way very often, you're more likely to be pessimistic, and really this optimism/pessimism side of things is just a proxy marker for your living conditions.

Olivia - It could be, however in this study they did take into account education and income, so people who have more education and higher incomes tend to live in nicer places. But they did account for this in this study and even after they took these factors into account it was interesting that optimism was still associated with a longer life span.

Chris - And do you think that these people are representative of the public at large, because they are specific groups of people that they study? I mean the veterans and so on, so do you think it's a reflection just on who they studied, or if I were to do this in a totally different geography, a totally different group of people, totally different culture, I'm gonna get the same thing?

Olivia - I do think inherently optimism is linked to a longer life span, because it's also been linked to just better health in general, and lower mortality rates. However, this study was you know, as you said, limited to a certain population, it was mainly white people of higher socioeconomic status Americans. So it would be useful to have this study replicated in other cultures, in other countries.

Chris - And the thing I'm really dying to know; say I was a bit less optimistic than I am or if I become even more optimistic than I am, will I gain 15 years? Does it work like that?

Olivia - I mean, why not try it out and find out.

Chris - It's a once in a lifetime experience, isn’t it? What about if I'm wrong? But no, more seriously can you make yourself into an optimist and does it then play out that you will live longer? Is it a reflection on your mindset in that way, is it cause or effect?

Olivia - If you are an optimist then that is better for your health, it is better for your lifespan, and you can become an optimist. So one of the things that you can do, is to just picture positive scenarios. If you've got a work meeting coming up, or if you've got an interaction with someone, you know, like a social gathering, instead of picturing all of the negative things that are going to happen, as often happens and when you have anxiety or depression, why not picture a very positive outcome, and how you're going to do so well and succeed in that environment.

Chris - Easier to say, hard to do!

Olivia - I would tell people to just give it a try because, even if you don't feel like doing it, motivation comes after action. So give it a try, and motivation will catch up with you...

10:43 - New target for malaria

New target for malaria

Andrew Tobin, University of Glasgow

Every year malaria kills nearly half a million people, most of them children. The cause is the plasmodium parasite transmitted by mosquito bites. Unfortunately, the parasite is rapidly becoming resistant to our current anti-malarial drugs. Now, scientists have uncovered a vulnerability in the parasite that can stop it in its tracks. It’s a crucial molecule - called protein kinase PfCLK3 - that’s essential to the parasite. Andrew Tobin and his team at Glasgow University have found a way to block it, and he spoke to Katie Haylor...

Andrew - The world does have very effective treatments, and those treatments have seen a reduction in the amount of malaria in the world. However, the parasite is able to adapt. We're seeing evidence of resistance to the current frontline treatments. We need new medicines with new molecular mechanisms of action.

Katie - Tell us about this treatment then, how does it work compared to the treatments we've already got?

Andrew - This treatment targets a very specific protein in the parasite which is essential for the parasite to survive. This protein is involved in producing the messenger molecules that make other proteins. Your protein is encoded on DNA. You need to transfer that code in order to get converted into protein and that's done using a molecule called RNA. But the RNA needs to be chopped up before it can effectively be used to make protein. Our target is involved in cutting up that RNA and by interfering with that process we stop essential proteins being made in the parasite. We’ve picked protein kinase PfCLK3 because we suspected that this protein kinase needed to be active in multiple stages of the parasite lifecycle. So by inhibiting our protein kinase, we prevent essential production of proteins and have therefore a very effective medicine for malaria.

Katie - How do you know that this works?

Andrew - Firstly you need to make sure that it works in the test tube against your target. Does it kill real malarial parasites which we culture in the lab here in Glasgow. It kills the parasite. Now you've got to know whether or not the different stages of the parasite lifecycle are killed, and then you've got to ask the question: can you actually cure an animal that's infected with malaria. And we go to a mouse model there to see if our compound can prevent the infection of the parasite in the mouse model. And finally we asked the question whether or not our inhibitor can stop insects from being infected and therefore be a transmission blocker as well as a cure. And it does. Treating the mouse with our compound prevented the mice from contracting mouse malaria. And remarkably, and these are extraordinary experiments because you have to feed mosquitoes with red blood cells that have been infected with the malaria parasite. And we find that by treat in the blood before the insect feeds on the blood, we can prevent the insect from becoming infected with malaria.

Katie - And that stopped transmission.

Andrew - That did indeed. And so that's a really critical experiment because if you want to eradicate malaria you need to prevent the transmission through the insect.

Katie - You need to get it into humans though I imagine next, so how do you envision that happening?

Andrew - The way that you do that is to now take your current drugs and develop them so that they become more effective but importantly they become safe for human use. And so we have a pipeline of experiments now involving all the major players in the drug discovery area: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Medicines for Malaria Venture, Malaria Drug Accelerator. These organizations will help us refine this drug optimize this drug and develop it for human use.

Katie - The problem is, there's a new drug, then the microbe genetically changes to counter that drug. Aren't you going to run into the same problem with this?

Andrew - I don't see there's any question that the parasite will become resistant to our new drug. This is why antimalarials are given in combination. But even then, resistance still develops and we will just need a new drug after a while.

15:12 - Mars solar conjunction

Mars solar conjunction

Paul Meacham, Airbus

There’s something getting between us and the rovers on the Martian surface collecting data... Adam Murphy has the details.

Adam - NASA's Curiosity rover has been trundling around Mars for nearly eight years now, dutifully sending back data giving us brand new information about the red planet. But from the 28th August until the 7th September, NASA will stop sending signals to Curiosity and all their other rovers. But what sort of thing could possibly get between NASA and their beloved rovers? Well, it's one of the biggest things that could get in the way.

Paul - Something is occurring called a solar conjunction. In simple terms, Mars is on the opposite side of the sun to the earth and thus the sun is blocking the direct line of sight.

Adam - That's Paul Meacham, lead systems engineer for the ExoMars rover at Airbus.

Paul - Because there is no essentially relay system to sort of bounce the signal either side of the sun, what you end up with is effectively a communication blackout period where you cannot talk to the rover and it cannot talk to you.

Adam - It's a bit like an eclipse, but instead of something blocking out the sun, the sun is quite rudely getting in the way of Mars. And we have no way to bounce signals around something as absolutely massive and enormous as the sun. So does that mean we have to completely shut down all of the rovers?

Paul - It depends on exactly where they are in the mission, and what their particular science goals are. I think the NASA rovers do have some sort of background scientific tasks they are able to do whilst it is essentially blacked out. So the NASA engineers have been uploading activity plans lasting about two weeks to allow them to do that.

But certainly anything that would require some sort of oversight from Earth, even if the rover was doing it autonomously, like driving or some sort of scientific experiment, cannot be done.

Adam - So it's just crunching some numbers, doing the bare basics parked somewhere safe. You don't want to park your very expensive rover on a sandy hill and hope for the best! Powering these rovers down isn't that dissimilar to putting your computer into sleep mode, still ticking along doing nothing too intensive. You just want the essential systems on. So what are the essential systems?

Paul - The communication system, the power system, and the computer, all of which will be in a sort of a low power configuration and sort of waiting to almost be woken up. But because it’s sometimes a bit difficult to predict when the first signals will come back, you have to lead the rover in a configuration where you can talk to it as soon as the solar conjunction in this case is over. So primarily it's just having your essential equipments on in as lower power mode as possible.

Adam - So the Mars rovers will be getting a much-deserved holiday and we'll be back trundling around the planet very soon.

18:10 - Black hole collides with a neutron star

Black hole collides with a neutron star

Joris van Heijningen, UWA

In 2015, the LIGO/VIRGO collaboration announced the first ever detection of gravitational waves, and won the Nobel Prize. Gravitational waves are ripples in the very fabric of space and time that are created when heavy objects move in certain ways. If you rotate your hands around each other, right now, you’re actually producing gravitational waves, they are just so tiny that they could never be detected. In order to produce detectable waves, the sources need to be much, much bigger. But LIGO didn’t stop after those observations in 2015, and, to tell us about some fascinating new gravitational wave results, Ben McAllister spoke to Joris van Heijningen, from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery, OzGrav, at the University of Western Australia. Joris didn’t work on the new result directly, but he does work with LIGO/VIRGO...

Ben - It’s September 2015 and two laser beams are travelling down two perpendicular four kilometre long tunnels. The lasers are making extremely precise measurements of the distances between two sets of mirrors, one mirror at either end of each of the tunnels. Why are they doing this? Well, that's a fair question. If a gravitational wave, a ripple in the fabric of space and time, were to travel through those tunnels, it would ever so slightly change their length as it travelled by, thus changing the distance between the mirrors, and scientists would be able to detect it. And that's exactly what happened. A long time ago, 1.3 billion years to be precise, in a galaxy far far away, two black holes each weighing tens of times the mass of the sun were rapidly rotating around each other, moving at half the speed of light. Then they collided and merged. The resulting gravitational waves travelled at the speed of light for 1.3 billion years to be detected by LIGO with their tunnels and lasers.

Now let's back up for a minute. Just in case you don't have a degree in astrophysics, I asked Joris van Heijningen what exactly is a black hole.

Joris - So a black hole is a result of a collapsing star.

Ben - And these aren't just any collapsed star corpses, these star corpses are so dense that nothing can escape their gravitational pull, not even light. Well, nothing except gravitational waves, that is. Since the initial observation of black holes colliding with each other, the team hasn't looked back. They've since observed more collisions between black holes, as well as collisions between interesting astronomical structures known as neutron stars.

Joris - The neutron star is also products of a dying star. The star explodes and all matter collapses down to something that is under very high pressure, all the protons and electrons smash together into neutrons to form a neutron star.

Ben - One of the reasons these results are interesting is because we don't really know a lot about what neutron stars are made up of and these observations may help us learn more.

Joris - what scientists call “the neutron star equation of state” is one of the holy grails in astronomy these days. This equation of states basically tells you what the inside of a neutron star is made up of.

Ben - But it isn't all just black holes merging with black holes and neutron stars merging with neutron stars. The LIGO-Virgo team recently announced that they believe they've spotted something different for the first time ever. Something which actually occurred 900 million light years away, 900 million odd years ago.

Joris - On the 14th of August, just before midnight European time, we saw a signal that may be a neutron star-black hole event. It was very loud. So we're pretty certain that this signal is real. However we are not certain what's the lighter object is.

Ben - Okay. But to clarify, it's a collision between two objects, one that we think is a black hole and one that we think is a neutron star.

Joris - Yes that's correct.

Ben - Frequently, gravitational wave observations are accompanied by corresponding signals of light like for example when they first observed two neutron stars colliding back in 2017. But as the LIGO-Virgo team found with this observation that isn't always the case.

Joris - The August 2017 binary neutron star merger gave lights across the spectrum. So far we haven't seen any light. If that turns out not to be the case when astronomers stop looking there it could mean two things. It could mean that the neutron star was gobbled up a whole, a little bit like a pacman, or it could be that the lighter object was actually also a black hole.

Ben - With observations like these, we're now entering what some scientists are calling “the era of gravitational wave astronomy”, where we're able to use detectors like LIGO and Virgo to detect enormous universe shaking events like collisions of black holes and then tell traditional astronomers with regular telescopes where to point those telescopes in order to pick up the corresponding light signals.

Joris - We are just having our detectors in observation mode. And then it's just waiting for the signal to come.

Ben - They're expecting many more observations in the future and more results like these ones could help us uncover the mysterious nature of neutron stars. Despite the fact that these gravitational wave observations sometimes don't give off any light at all, the future looks bright for LIGO-Virgo.

Joris - We will continue measuring gravitational waves. One thing that we still want to measure is a supernova in order to understand more about these events. And we need more of these binary neutron star events to determine this equation of state.

Ben - With gravitational wave detectors only getting more and more sensitive, we're sure to learn plenty more incredible things about the universe!

Chlamydia

Caroline Cooper, iCASH Cambridge

Chlamydia is one of the most prevalent sexually transmitted infections in the UK. To find out the scale of the problem, how it can be treated, and how far we might be from a vaccine, Chris Smith and Katie Haylor spoke to sexual health doctor Caroline Cooper from Cambridge. First up Chris asked Caroline how much of an issue STIs are in the UK in general...

Caroline - Well, certainly the rates of sexually transmitted infections are increasing year on year across the UK. I think it is an important issue. In particular, infections like chlamydia are becoming more common.

Chris - And when you say the rates are high, how high?

Caroline - For example chlamydia, there's about 220,000 new cases in the UK last year.

Chris - I did see some statistic of about 10% of 16 to 19 year old girls having it in this area. I mean that's quite high. Isn’t it?

Caroline - Yeah, certainly, it’s prevalence in the UK is somewhere between nine and eleven percent. And I think one of the challenges with chlamydia is that often people don't have any symptoms. About half of men and up to three quarters of women don't know they've got it. So they have no reason to go and be tested or go and seek help from a professional.

Katie - Also with us is Graham McKinnon. He's a sexual health doctor from Peterborough who specializes in HIV. Graham, what is the most common issue you see in your clinic?

Graham - I mean the most common issue is when you get someone coming in and they're worried that they've got something, they're worried that they've picked up an infection. They want to know what it is, they're worried whether it's going to affect them, maybe affect their partner. And you know they want to sort of get it sorted. And often they're quite embarrassed about things as well, we try to deal with that.

Chris - A very warm welcome to both of you. As Caroline alluded to, chlamydia is a major problem. So that's the first thing we're actually going to look at this week. Here's Phil Sansom with the quickfire signs of it.

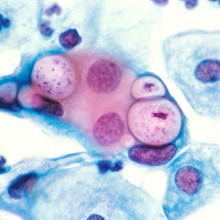

Phil - Chlamydia is a bacterial infection. It's one of the most common sexually transmitted infections in the UK. It's easy to be infected with it without realizing, because many people with chlamydia have no symptoms. For those that do have symptoms, they can become apparent a few weeks after you're infected. You might experience a discharge from the vagina or penis, or a burning sensation while urinating. For women, there may also be bleeding after sex or between periods. For men, there might be painful testicles. The long term consequences can be varied and severe. For women, chlamydia can cause pelvic inflammatory disease which can affect fertility. In men, testicles can become inflamed and if not treated there could be a risk to fertility. It normally only takes a urine test or a swab of the relevant body parts to diagnose chlamydia and you can treat it with a course of antibiotics. It's a good idea to get checked regularly if you're sexually active. There is currently no vaccine for Chlamydia, but a group of Danish researchers are about to start the second stage of clinical trials on a possible candidate.

Chris - Interesting stuff. So Caroline, when someone has chlamydia, we've heard there that it can be asymptomatic, it can be smouldering away inside. What sorts of things actually happen when you get things like pelvic inflammatory disease, what are the consequences?

Caroline - Certainly chlamydia when untreated can lead to widespread pelvic infection. So this can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, it can also lead to ectopic pregnancies where a woman will have a pregnancy outside of the uterus, most commonly in the fallopian tube, and in some women it can lead to infertility. So you know it's a potentially very serious condition.

Chris - What happens if someone contracts this when they are pregnant? Or if they’ve already got it and then they get pregnant. Because you've said it can be asymptomatic.

Caroline - Yes certainly. We would always encourage women to have treatment during pregnancy. It doesn't have any implications for the delivery, but for some of the babies born they can have eye infections. They can sometimes have quite a severe lung infection.

Chris - And is it relatively easy once you've got the diagnosis to actually treat it?

Caroline - Yes. So the treatment is very straightforward. We have extremely sensitive tests now. We have antibiotics that will treat chlamydia that are extremely effective.

Chris - Because with some of these infections we've seen that the bugs are becoming resistant to the drugs. That's not the case for chlamydia is it?

Caroline - It's not such a problem for chlamydia. Certainly the widespread resistance to treatment we're seeing with infections like gonorrhea, like Mycoplasma genitalium. But at the moment we're fairly confident with our chlamydia treatments.

Chris - Why do you think in recent years this has become such a big problem, because it wasn't such a big problem historically and it seems to have really grown. Why is that?

Caroline - Well I guess part of the reason is that people don't always know that they've got it. I suppose another reason is the changes culturally, in that people are having more sexual partners over their lifetime, and having more frequent change of partners. And once you've got the infection, up to 85% of your partners are likely to have it too.

Chris - So it's pretty easy to catch.

Caroline - Yes certainly it is. It generally would be caught through having either vaginal sex or anal sex with someone who's infected.

Katie - So if we take a step back, what is the main way of preventing getting a chlamydia infection?

Caroline - Well, I suppose it's the same as the ways that you would prevent getting any sort of STI. It would be having protected sex using a condom and having regular checks. Certainly, I think you mentioned at the beginning how common it is in young people. And we would encourage everyone under the age of 25 to have an annual checkup, or to have a check anytime they have a new partner.

Katie - The piece that we just heard also mentioned a vaccine for chlamydia, that's that's undergoing trials at the moment. So tell us about that. How does that work?

Caroline - This is potentially a very promising vaccine. The early trials were just on 35 women but they found that it was extremely successful in provoking an immune response. So the women produced antibodies to chlamydia both in their blood and in vaginal fluids. And certainly, the vaginal fluids would be the first line of defense against chlamydia. Obviously we now need much larger numbers of people to see if it will actually prevent chlamydia as well as producing the antibodies.

Chris - What's the nature of the vaccine, how do you administer that, is that an injection?

Caroline - In the trials it was a course of three injections and then two nasal sprays. But it's felt that continuing injections would be enough.

Katie - We were talking just a moment ago about the fertility implications for women. What about men?

Caroline - There is some suggestion that for men it can cause them to have inflammation, infections in the epididymis where the sperm is produced, and so that would have implications for their future fertility as well.

Chris - Is there any way for a person who gets treated, clears the infection, and now can be regarded as uninfected, to find out if it's had any long term consequence on them or do they have to wait and see?

Caroline - I think that is a real dilemma because there isn't a particularly easy test of someone's fertility after Chlamydia. You know, we can say statistically if you've had one episode you may be at risk of infertility. The more times you get it the higher your risk. But there's not really an easy test. So I think it is a bit of a dilemma for people.

Sexual health check up

Meg Veit and Grant Chambers, Dhiverse

When was the last time you went for a sexual health check? It might feel a bit daunting, but regular check ups are important if you’re sexually active. To find out what goes on, what might get looked at, and what tests are involved, Katie Haylor headed over to Cambridgeshire sexual health charity Dhiverse to meet Meg Veit and Grant Chambers...

Katie - Hello! Are you Meg?

Meg - I’m Meg, nice to meet you!

Katie - Nice to meet you.

Meg - And this is Grant.

Katie - Hi Grant. I’m Katie.

Meg - My name is Meg. I am the young people's service manager at Dhiverse, we do all sorts of things including HIV support, but also education and training for young people, professionals, people with learning disabilities, physical disabilities and really anybody that wants to learn about sex and sexual heath.

Katie - Right. Meg, I walk into a sexual health clinic. What happens?

Meg - You'd speak to the receptionist, and then when you go in, you’d speak to a sexual health nurse or doctor, they'd ask you some questions about who you are, your health, and your lifestyle, and then also often about the kinds of sex that you've had before. These questions aren't to be invasive or to judge you, they're just about working out what kind of tests you need.

Katie - And those tests could involve weeing in a pot, using a swab in your vagina, or in your anus, or in your mouth, and you might need to do a blood test. It's not always necessary to actually look at your bits, but it might be.

Meg - If you have symptoms, so maybe you have some lumps and bumps or sores that you want somebody to have a look at, and that's why you were there, then they would ask to have a check. They're very good about making you feel comfortable and you can also bring somebody with you. You can have another person in the room, but you don't have to do that every time. And if you have no symptoms it's unlikely they'll want to see you naked.

Katie - And how long might I be waiting for my results?

Meg - Takes about 10 working days and then they'll give you any follow up advice after that as well.

Katie - And if the test is positive?

Meg - So they might prescribe you some treatment, see if you need some follow up appointments. There's no STI you can get where they can't help you manage it. A lot of STIs are curable as well. They also might refer you to get some psychological support if you feel like you might need help with how you feel about that diagnosis, which is something that we offer free here at Dhiverse with our trained counsellor.

Katie - Dhiverse do a couple of STI tests, one being for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, which is a test that they offer to young people in Cambridgeshire, and Meg took me through it.

Meg - I’d give you either a little swab, and there's also a little pot which is for doing a urine sample. So it was just a little wee sample, you could just go and do these on your own in the toilet and then bring them back to me when you're finished.

Katie - Almost like a film canister, but see-through, and presumably you need to have quite a good aim?

Meg - They are a little bit on the smaller side I'll give you that. It's worth noting that we put it inside another pot, and put the lid on, so if you do splash wee on the outside, it's really not the end of the world.

Katie - OK so it's not that big a deal.

The vaginal swab looked just like a cotton bud you might use to take off mascara, but with a much longer handle.

Meg - The cotton bit, that's the only bit that needs to go inside your vagina. Just need to put it in for a few seconds. The key is to give it a nice little twizzle while it's inside. You just pick up those cells to make sure you get a good sample and then put it back in the little tube it comes in. You don't need to shove it all the way up there, which is a mistake that I made in my youth. You only need to put it in a little tiny bit and you hardly feel it at all. If you come back positive for chlamydia or gonorrhoea, it’ll be a little course of antibiotics and then another test to make sure that it's definitely gone.

Katie - If my test result is positive, what about my sexual partners?

Meg - So one of the things that's really really good about sexual health clinics, is they have a service to help you do this. So if you think there's anybody that does need to know they can actually send messages around for you anonymously.

Katie - Another test the diverse team can do is for HIV. It's called an INSTI test, and you get the results there and then.

Grant - So my name is Grant and I'm the health promotion and training manager for Dhiverse. But one of the little extra things which I do, is I can give people finger prick tests for HIV. And that's what's in front of me at the moment. It just contains various chemicals, a little lancette with which you can prick your finger, the same kind of thing that you would use to test your blood sugar levels if you were diabetic.

Katie - Grant explained the reason they do these INSTI tests is because although it's possible to manage HIV very effectively with treatments, late diagnosis can be a problem. If you only become aware you have HIV when you start to get ill, treatment can be a bit more difficult.

Grant - So we really want to make sure that people living with HIV find out about that as soon as possible so that they can start on treatment, and that's what this service is about. We do need to have a chat beforehand to make sure that someone can give informed consent to have the test. And that's really because you get the result there and then. So we need to make sure that they are prepared and they've got the right information to be able to process that result when they get it. So the lancette is this little yellow cylinder. You just press it down and then, it’s a little blob of blood. You gather the blood in a pipette, and you put it in a little cup shaped container. Add various different chemicals, and like some pregnancy tests the results are determined by the number of dots that appear. So if no dots appear, that means the test hasn't worked which is quite unusual. If one dot appears that means the test has worked and it's saying that your negative, non-reactive I should say. And if two dots appear that means the test is reactive and it's saying that you do have HIV.

Katie - Grant did note that this particular test has a false positive rate of 1 in 200.

Grant - So it says you have HIV, but in one in two hundred cases you don't have HIV. So every time we have a positive, a reactive result, we fast track that person to one of the sexual health clinics so they can have a checkup, have an intravenous blood test and get their medical follow up that they need. We can offer psychological support around some of the social issues, for example coping with prejudice and stigma around HIV.

HIV

Graham McKinnon, iCASH Peterborough

Around the world, almost 38 million people were living with HIV/AIDS in 2018. To find out how HIV is diagnosed and treated in the UK, Chris Smith spoke to sexual health doctor Graham McKinnon. First, here's Phil Sansom with the Quick Fire Science...

Phil - HIV is the human immunodeficiency virus. And around one in six hundred fifty people have it in the UK. Often the only symptom is a short flu like illness, a few weeks after the infection which lasts for a week or two. However long after this symptom disappears, HIV is infecting and damaging vital cells in your immune system. This can lead to AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

If you have AIDS your immune system has become severely damaged by HIV. You become vulnerable to a whole host of potentially life threatening illnesses from tuberculosis to cancer. HIV is diagnosed with a blood or saliva test at a clinic or using a kit at home. The earlier it's diagnosed the quicker you can start treatment and the more chance you have of controlling the virus. The treatment consists of daily tablets called antiretrovirals, which stop the virus from replicating itself. Often you need a combination of different antiretrovirals, as HIV can quickly develop resistance to a single one. There is no cure for HIV or AIDS. However with enough treatment you may eventually have an undetectable viral load meaning you have so little of the virus in you that you won't even transmit it.

Chris - With us is sexual health doctor Graham McKinnon. He has a special interest in HIV. What actually does that mean when we talk about viral load Graham and undetectable viral load. What's the implication of that?

Graham - It’s essentially the amount of virus that you have in your blood. So we measure it in terms of copies per milliliter of blood, and someone with HIV who's not in treatment might have 10,000 copies per ml of blood or millions if it's early on in the diagnosis. But essentially what treatment does is it brings down that virus level to undetectable levels.

Chris - And if you can't detect it does it go therefore that you can't transmit it?

Graham - Exactly and this is one of the big things that we've learned recently from big studies which have looked at couples where one person has HIV and one doesn't. If you're on treatment there's zero risk of transmission. We call it U = U, because undetectable equals untransmissible.

Chris - And obviously that's a mainstay of trying to deal with the HIV epidemic, because if you've got people who can't transmit, it then they're not going to give it to other people. And therefore we're not going to grow the epidemic as fast as we were.

Graham - Absolutely and we've seen in the UK, so 2017 there was 4000 new cases of HIV, compared with about 6000 in 2015, and part of that is because of rapid access to treatment people going on treatment early.

Chris - So if you can suppress the virus down to the point where you can't detect it, why does it come back at all?

Graham - If someone stops taking their treatment, what happens is that the virus in your immune cells, that are sleeping if you like, the virus in there can wake up and when those cells wake up they reproduce virus and then that fills the blood again.

Chris - And how do the drug regimens actually work to control the virus?

Graham - So the drug regimens are clever in that most of my patients are on one or two tablets and they've got two or three different drugs in them and they act on different parts of the virus replication cycle, blocking at different levels, which then stops it reproducing itself.

Chris - What are the strategies that we're using, beyond just managing people who've already got it, to stop people getting it in the first place? Because those same drugs are being used in that context aren't they?

Graham - Yes, so as well as testing there's also something called PrEP which is pre exposure prophylaxis. So the idea here is that you give people who are at the highest risk of HIV a drug called Truvada which is a drug used to treat HIV and they take it every day, or around the time that might be having high risk sex to reduce the risk of transmission. Of course condoms are also another way of preventing HIV transmission.

Chris - Sure. But if that person who is on that preventative medicine encounters someone who's got a form of HIV that is resistant - because this happens doesn't it, to that drug you're giving them - they wouldn't be protected would they? So might they not be in a false sense of security if they're doing that?

Graham - Actually when you look at the rates of resistant virus it's actually very very low.

Chris - Any other preventative strategies? I was in South Africa last week they said they have a very big program there for circumcision because this has been shown to be very effective in reducing transmission in some cases.

Graham - Yes. So there is evidence that men who are circumcised there's less carriage of the virus between the foreskin and the head of the penis itself. That's not something that we're looking to introduce in the UK. I think one of the key things actually is testing.

Chris - Because if you know you've got it you're going to take steps to make sure you don't pass it on.

Graham - Yeah. If you know someone's got it you going to go on treatment so you're going to have an undetectable viral load and you're going to live a long and normal life. It's best for you as well.

Chris - Obviously the number one goal in everyone's mind is that we need a vaccine for this thing. Where are we on those stakes?

Graham - So the problem with developing a vaccine for HIV - because people have been looking at this for years really to see if we're able to do this - is that HIV changes itself. So some of your listeners probably get a flu vaccine and every year that flu vaccine is slightly different. But HIV changes far more rapidly than the flu virus. So developing a vaccine has been difficult because the virus changes so rapidly.

Chris - Last thing I want to dwell on a bit because it often gets overlooked, and that is that people who catch HIV very often get pregnant at the same time. And so you end up with someone who is pregnant and has HIV. How do we manage people in that situation?

Graham - So I myself have diagnosed people who are pregnant and with HIV and it's a devastating thing because they're worried about themselves they're worried about their baby. But I think the key message to get across is that they go on treatment and actually with treatment they get an undetectable viral load. And actually they can have a normal vaginal delivery and not pass on the virus to their baby.

Chris - So what fraction of women who have a normal delivery and are HIV positive will pass their virus onto their baby?

Graham - We’re looking at less than one in two thousand.

Chris - So a well managed person has a fraction of a percent chance of actually passing it on?

Graham - Yes, it's very encouraging. It's amazing what treatment has done and changed over the last 30 years.

Chris - And what should someone do if they're worried that they might have encountered HIV? What would be the appropriate guidance?

Graham - So what they should absolutely do is come to a sexual health clinic, and we can test you, we can counsel you, we can get you sorted.

Chris - But there is a chance when you first encounter HIV, that you're not going to test positive straight away. And what do you do under those circumstances? How long does it take before you do register positive on a test?

Graham - So the test that we use in our sexual health clinic and that other clinics use has a four to six week window period. So if someone's had sex four weeks ago, and I test you and your test is negative we can be very confident that you've not got HIV. But if it's within that, we'll still test you but would ask you to come back for a repeat test at the appropriate time.

45:54 - HPV

HPV

Caroline Cooper, iCASH Cambridge; Graham McKinnon, iCASH Peterborough

From September 2019, boys will be offered the HPV vaccine, as well as girls. To find out more about the virus, how it's tested for, and why the UK vaccine protocol has changed, Chris Smith and Katie Haylor spoke to Cambridge sexual health doctor Caroline Cooper...

Phil - HPV is a group of very common viruses, called the human papilloma viruses. Most HPV infections pass through you without any symptoms, but in some people some viral infections lead to genital warts. A doctor can usually diagnose this by a quick examination, and you can treat them with a cream, or with surgery, or by freezing them. Other HPV infections can be more serious and put you at risk of different types of cancer. Cervical cancer in particular is nearly always due to HPV. Testing for it means a cervical screening. The NHS offers this, by invitation, to all women and people with a cervix aged 25 to 64. There is a vaccine for HPV, and starting in September all schoolchildren aged 12 to 13, no longer just girls, will be offered the vaccine.

Chris - I know that when we first began talking about HPV on this programme, it was in 2005, and we invited Margaret Stanley who was one of the architects of that vaccine, actually here from Cambridge, to come in and tell us about it. People were shocked to learn that cervical cancer is a sexually transmitted disease. Caroline how does this virus actually cause disease?

Caroline - The HPV can cause cancer by damaging the cells in the cervix and it's a persistent infection. And the damage to the cells can lead over many years to the changes that could become cervical cancer.

Chris - It's really common isn't it? And so only a fraction of people who actually encounter the virus go on to get the disease. Do we know why?

Caroline - Absolutely. And we don't know why some people will go on to develop cervical cancer and others won't. I think it's important to know that the human papilloma virus can also cause other cancers of the head and neck, the throat, and other genital cancers in both men and women.

Chris - And the vaccine will combat all of the above will it?

Caroline - The vaccine that's currently being used in the UK is incredibly effective. We've already seen a decrease in the number of warts that we're seeing in our clinics.

Chris - Yes because the virus also causes genital warts as the piece we’ve just heard there said

Caroline - Certainly in the women under 18, there's been a 92 per cent fall in warts over the last five years. So you know it's a staggering effect. Obviously it's going to be some years before we'll see the decrease in cervical cancer, because that takes longer to develop. But certainly the vaccine that's being used will prevent up to 90 per cent of cases of warts, and 70 percent of cervical cancer.

Chris - The way in which we go about cervical screening has changed in recent years though hasn't it, compared with previously, where we used to take a smear and look at cells under the microscope. Now people are taking a swab and they're looking for the DNA of the human papilloma virus. Why has that been that shift? And is this going to be as good, or better?

Caroline - And that's right. And you see now that we know so much more about the development of cervical cancer, and we know that it's so strongly linked to HPV, that instead of looking under the microscope at smears from all women, we are screening women by testing them for high risk HPV. Those that don't have high risk HPV don't need any further testing, and those who do will then have their slides looked at in the same way as we did in the past.

Chris - Does it have less of a failure rate? Because lots of people previously were having to come back because they got inadequate smears and so on, is it better in that respect?

Caroline - It's better from that point of view, and it means that less women are going to be having the unnecessary and very worrying investigations and treatments that they were having before. And we want to make sure that we're just picking up the women who've got the disease, rather than screening too many healthy women.

Katie - Now Graham cervical screening is obviously important for women but what is the risk for men when it comes to HPV.

Graham - So as Caroline alluded to, HPV can be linked to other cancers as well, such as head and neck cancer. In recent years seen it associated with some forms of oral cancer, anal cancer, penile cancer vaginal and vulval cancer, now they’re rarer forms of cancer but is associated with all these different sorts so it's an issue for men as well.

Katie - How do you test if a man's got HPV. You can’t obviously do a cervical screening.

Graham - Yeah, and this is the issue there's not screening programs for things like anal cancer in the UK, or indeed in many countries, because there’s not a good screening test.

Katie - So what do you do?

Graham - You look at vaccinating men, and that's something that has been introduced now. So from autumn this year boys aged 12 to 13 will be vaccinated as women have been as well. And that's a key kind of weapon in our arsenal in combating HPV in terms of causing cancer for this group.

Katie - Do we have an estimate of how impactful that will be? Because obviously it was just girls who were being vaccinated for a good few years before.

Graham - Yeah. In Australia they've been using this vaccine since 2013. You know, in terms of cancer, that's still very, very early, because cancer takes many, many years to develop due to HPV, but all the data from Australia shows that you're getting less high risk changes, less infection with the HPV types that can cause these cancers.

Katie - Do we know who's most at risk when it comes to HPV? Does it break down by any particular demographic? Is it certain age ranges?

Graham - I mean, I think the important thing to say is that, in terms of if you look at all HPV types you know, 90 percent of the population are going to be exposed to an HPV type, it is a really common virus. It’s more normal to have it than not have it but you know, obviously increased numbers of sexual partners, then you’re more at risk as you are of any sexually transmitted infection.

Katie - What would you see as being the main challenges for tackling HPV going forward then?

Graham - So I think one of the exciting things that's in development, they're looking at now a vaccine that's got nine HPV types in it, because as Caroline said you know, the current vaccine will protect against 70 percent of the HPV types that cause cervical cancer, but actually the nine valent vaccine will up that 90 percent, so I think that's the development.

Safer sex

Caroline Cooper, iCASH Cambridge; Graham McKinnon, iCASH Peterborough

STIs aren't just affecting younger people - they can be a problem at any age. And there are many more than the three we've discussed in the show - chlamydia, HPV and HIV. Chris Smith and Katie Haylor got some closing thoughts from sexual health doctors Caroline Cooper and Graham McKinnon...

Caroline - Well certainly a lot of the sexual health promotion and prevention is aimed at the under 25s but obviously STIs affect people of all ages. And we certainly have seen an increase in people over the age of 50 being at risk of STIs. And if you think that's the time when often people are coming out of marriages, or long term relationships, and may not have experienced the education around STIs and may not realize that they need to have regular testing and treatment when they have new partners.

Chris - For those also the stigma and the concern, the embarrassment factor, might be greater than it is for younger people who by and large seem to be more comfortable with engaging with screening services like those that you offer. So is there anything that someone who is a bit embarrassed, or is in that older group and might not want to go off to the clinic, is there anything they can do to get screened?

Caroline - Yeah absolutely. I think that the younger people are very chilled and they'll be in the clinic chatting to each other. And I had a teacher last week who was mortified that she might bump into one of her students. And certainly for anyone who doesn't want to come to a clinic, either because they're embarrassed or really just for convenience of having to make the time to get an appointment, there's been a rise in online testing over the last few years, and it really couldn't be easier. You can order a testing kit online. For men and women you do a finger prick blood test which will test for HIV and for syphilis. And women can do a vaginal swab to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea and men can do a urine test.

Chris - How do you get do you get the result?

Caroline - The results will come by text, so you send that kit back in the post but you'll get a text and that'll usually be within a couple of weeks. With any positive results you would want to contact someone by phone. So negative results would come by text and it would usually be a phone call with someone who's qualified to have that discussion. Certainly in Cambridgeshire when you're ordering the tests online we have a bit of a screening that people will go through around their risks to make sure that we're having the right test for the right person.

Katie - Caroline, these online tests. Is this a national service in the UK?

Caroline - Yes. I mean they're available all over the UK, generally run out of the local sexual health clinics with different availabilities in different areas. But certainly if you Google sexual health and the name of your town or city you'll get the information.

Chris - And obviously one has to be aware of the fact that a lot of these tests are designed to be excruciatingly sensitive so that we don't miss any cases. But that does mean you have to prepare yourself for the fact that - as Katie heard in her clinic visit - you're going to get a number of false positives.

Caroline - Absolutely. And I think that that's one of the things that we would want to discuss with someone you know in a telephone call if we had any positives.

Katie - Graham, can we bring you in here? What are your closing thoughts on this? We've talked about three particular STIs in this program but there are far more than three.

Graham - One of the things I say to people in clinic when we test them - because we don’t just test for chlamydia - gonorrhea, HIV, syphilis, sometimes trichomonas, sometimes hepatitis. If they’re a bit reluctant about having a blood test I'll say “STIs are a bit like like hyenas, they hunt in packs”. So you know if you've got one you might have another. So it is always good to test for multiple infections where appropriate, and that's what we do.

Katie - I heard on the grapevine that you've been doing some work on an STI I had never even heard of actually. Is this mycoplasma genitalium?

Graham - So mycoplasma genitalium is something that increasingly over the last four years we’ve become more aware of in the UK, and now a number of sexual health clinics are testing for. It's a small tiny bacteria. It's a bit like chlamydia but it doesn't get transmitted as easy as chlamydia, but it causes similar kind of problems.

Katie - Is the treatment similar?

Graham - The treatment is not similar, it's not straightforward to treat. It has got resistant to some of the first line antibiotics that we use, so often we have to go and do resistance testing as we get a positive result. And then treat with appropriate antibiotics. But we are able to treat it at the moment.

Katie - And all this talk about STIs, can we just get advice from you on safer sex and preventing these cases in the first place?

Graham - When I see someone in clinic I say “if you use condoms that reduces the risk of you yourself getting a sexually transmitted infection”. I also say “when you get together with a new partner, use condoms, both get checked out and then you know what each other has got and you’ve removed the mystery. Have that conversation, say “let's get a sexual health checkup”. Care about each other's health”, and I think that's an important thing to do as well.

Related Content

- Previous New producer of climate-cooling gas found

- Next Chlamydia

Comments

Add a comment