Waterloo Uncovered: Veterans Excavate Old Conflicts

This week we’re on the historical Waterloo battlefield where veterans of modern wars - often with disabilities, PTSD and other mental scars - are joining archaeologists to excavate remains of one of the most important conflicts in European history. Plus news that an anti-obesity pill might be on the scientific menu, and the space probe heading for the hottest part of the Sun...

In this episode

00:57 - Blocking intestinal fat absorption

Blocking intestinal fat absorption

with Sam Virtue, University of Cambridge

Fuelled by cheap calories and sugar-saturated treats and drinks too tempting to resist, the world is in the grip of an obesity epidemic with over a third of the human race now overweight. Carrying excess weight is a major risk factor for a range of disorders including diabetes, high blood pressure, heart attacks, strokes and joint problems. And given the rate at which the problem is growing, advice about healthy eating and calorie control is clearly not working, and the prospect of stomach stapling the world population is inconceivable. But might it be possible to produce an anti-obesity pill that can control how the intestine absorbs calories? Scientists in America have uncovered a system at work in the gut that can shut the door to fat uptake. Sam Virtue, from the Metabolic Research Laboratories at Cambridge University, took Chris Smith through the findings...

Sam - If you eat fat, pieces of fat come into a specialised cell called the enterocyte, and the enterocyte rebuilds the fat and exports them into ball-like object called chylomicrons. These then exit the other side of the enterocyte away from the gut and go into these small tubules called lacteals.

Chris - Once they’re in those lacteals they’re into the body and then able to get into the bloodstream and so on? So that’s the sort of gateway into the body isn’t it?

Sam - Yeah. It’s the gateway into a second circulatory system in the body called the lymphatic system. You may have heard of lymph nodes, and when you hear people saying "oh, my glands are swollen," that’s because the lymph nodes are swollen, and they have an important role in our immune system; but they also carry a milky-white substance called chyle round the body, which includes of all these fats we’ve absorbed from our intestines.

Chris - How have they looked at that transmission process between the cells lining the gut and those lacteals?

Sam - They’ve looked at a molecule which is called VEGF-alpha, and VEGF-alpha is a molecule that we’ve known for ages. It’s very important for controlling how your body makes new blood vessels. It also turns out it now has important roles in controlling this other circulatory system - the lymphatic system - and how those knit together. So what they’ve done is they’ve deleted two genes that negatively regulate VEGF-alpha to make it more powerful and work better. And they’ve found something really quite cool, which is these little balls of fat normally get into the lacteals and the lymphatic system through gaps between cells in these lacteals, because the cells are not very closely or tightly knitted together; in fact, the junction is described as a bit like "buttons". And, in fact, if you think about the fly on a pair of trousers, you can slot something between the buttons and the fly. Remarkably, when you add the VEGF-alpha, they turn into structures that look like zippers, and you cannot shove something through the gaps in a zip!

Chris - Effectively it closes the gateway? It’s locking up the cells tightly together so that they can’t export these balls of fat into those tubes that would then carry them round the body?

Sam - That is exactly the case. And because they can’t absorb them, the fats that should be absorbed remain in the gut and are actually excreted in the faeces.

Chris - If you feed animals a diet that would make a normal mouse become obese, one would presuppose, then, that these animals don’t gain weight. Is that what happens?

Sam - That is exactly what happens. The animals are normal on a low fat diet, but when you give them a tastier, higher fat diet - something more akin to a McDonalds or Burger King - the normal mice enjoy it and get much fatter; whereas these mice with these tight "zippers" that prevent the fat going into their bodies cannot get fatter and remain pretty much normal weight.

Chris - We do depend on fat absorption for really quite critical processes, don’t we? There are fat soluble vitamins: A, D, E, K, so if we clog up this process is there not a risk we could end up very deficient in some really quite important factors?

Sam - Absolutely! And there will be a need for further follow-up to see how practical this is and safe this will be if it’s ever to go forward as a treatment. There may also be impacts on other aspects of gastrointestinal health; does it affect nutrient absorption? Also, does it have effects on the microbiome of our gut and could this have other negative impacts? But it’s certainly a promising avenue for future research.

Chris - And talking about that future research, would the grand vision then be you could turn this on or off a bit to just tip the balance so you could still enjoy a few extra helpings of trifle and you wouldn’t pay the price with your waistline later?

Sam - Yeah. And I think that there are other aspects about this which make it quite interesting; one is that within the paper itself they do have a pharmacological inhibitor of this process. But one of the striking things is they show that physiologically, just in a normal gut, this process can happen very rapidly and be very rapidly regulated, and why the body has the sudden ability to shut off lipid absorption is one of the most interesting things. Generally, if you’re doing something that modulates something that the body normally does, and you can do it a bit, it’s often a healthier approach than something that’s really kind of alien if you’re looking to try and generate a treatment.

Chris - So you could literally pop a pill with a "bad for you" lunch - if you’re going to be really naughty and pig out, you could pop a pill and temporarily disable the system just for lunchtime and then return to full virtuousness by dinnertime?

Sam - That’s conceptually the case, but let’s just remember where the fat from that "naughty" lunch would go. One of the side effects you have to worry about with this kind of treatment is an unpleasant sounding thing called steatorrhoea, which is actually about as unpleasant as it sounds - it’s oily poos! So you would have to decide what you want to do with regards your lunch!

Chris - You know what they say: there’s no such thing as a free lunch… And that seems to put a nail in that coffin doesn’t it. Cambridge University’s Sam Virtue there, commenting on the paper in the journal Science by Anne Eichmann and her team at Yale University who made that discover...

06:52 - Exoskeletons, and Metal Organic Frameworks

Exoskeletons, and Metal Organic Frameworks

with Peter Cowley, Business Angel & The "Invested Investor"

Estimates vary but we think that an ant can lift between 10 and 50 times its own body weight. For a human, that would be the equivalent of being able to pick up a truck. Now it seems that the car manufacturer Ford is seeking to take a leaf out of a leaf cutter ant’s book and is equipping staff on the production line with wearable exoskeleton suits to help with lifting and reaching. So is this the future? Here to share his wisdom with Chris Smith on this and other technology developments is business angel investor Peter Cowley...

Peter - An exoskeleton is a skeleton outside the body, and so examples of those are crabs, cockroaches. Human beings have endoskeletons - our skeletons are inside us. The point about an exoskeleton is to assist the movement of limbs, so whether those are arms or legs in order to either replace that limb or to improve the ability to do something. And this example with Ford is for workers who are possibly working above their head height underneath the chassis of a car tightening up nuts and bolts, which is really hard. If you imagine eight hours with something in your hand, which might only weigh a kilo or two, it’s going to be really difficult. A lot of of strain on both your arms and your shoulders.

Chris - How does it work then? Just describe what it looks like this exoskeleton. Is it like an "exosuit" that you would step into and you’ve got a wearable robot effectively on the outside of you?

Peter - A good question, yes. In fact yes, they are working on those sort of things, and the military, particularly, are working on things. But these ones that Ford have got from a company somewhere in the States are actually really small. They’re only four kilos, they mount on your shoulders and around your waist, and they provide a relatively small amount of lift. It’s only adding two to seven kilos, which is still quite a bit compared with your normal arm.

Chris - How are they powered then?

Peter - They’re powered with springs so it’s spring assistance here. The big ones you mentioned before are powered with, in one case, a little internal combustion engine. So you’ve got a little petrol engine on there and batteries and things, and they’re huge and they can weigh a hundred kilos on top of your own body weight.

Chris - So it’s almost like an external angle poise lamp that you’ve got strapped to your arm but it means that sustaining a position or a posture for an extended period of time, you’ve got that extra bit of support and makes it easier?

Peter - It’s a bit more than angle poise because it will actually assist you with lifting as well. It won’t just stay in position as the microphone in front of you is, it will actually allow you to push up as well.

Chris - But there is no such thing in physics as a ‘free lunch’ so you can’t get a push for nothing. So if it’s sprung loaded the energy must be supplied by the wearer to move it?

Peter - Well, it’s actually redistributed around your body I think, rather than just in your arm. So it’s you shoulders and the rest of your body that’s helping that assistance.

Chris - What do the workers say? Is it going down well?

Peter - There were some prototypes out for some time. I’m just taking this, of course, from the internet and they’ve just ordered 75 sets of these in order to go out throughout the factories around the world. They’re not cheap though because they’re low volume so they’re talking about 6,000 Dollars for each one. This is something without any batteries, without any power, without any computing power, etc.

Chris - But they must have done some kind of cost benefit analysis and worked out that’s 6,000 well spent? They must thing they’re going to get that back in terms of productivity, or fewer lawsuits because someone gets repetitive strain injury type things on the production line?

Peter - Exactly, yeah. I don’t think it will be productivity because I think the line will still move at the same speed, but it will be in terms of strain injury, and people being off work, and potentially lawsuits.

Chris - What about extrapolating this to people who have disabilities, weakness or other kinds of problems that means something like this might help them?

Peter - Yeah. This comes back to what you’ve just said; it’s that a spring loaded device won’t do that, you need something that’s actually got it’s own power. There are a number of exoskeletons that are being experimented with and sold around the world, particularly in Japan for the aged. An example might be that a nurse needs to lift a patient regularly and move them around. You can’t easily do that if you’re a small lady nurse perhaps and how are you going to lift 70 kilos or something? They can do that with these suits on.

Chris - Now in other news: you mentioned to me that you have been looking at some technology that you’re thinking of investing in. Tell us about that...

Peter - Yes. I’m a very very active Angel investor and have invested in over 60 startups, some of which have failed and some have executed a good amount of return. And the one I mentioned earlier on is actually coming out of the Engineering Department here, University of Cambridge. The concept is if you have a cylinder of gas, at a certain pressure you’ve got a certain amount of gas in there. If you add something called a metal oxide framework, which I’ll come to in a moment, you can actually increase the amount of gas in there. The volume of gas in there at the same pressure, which doesn’t seem to make much sense in principle because you’ve got more material in there, in the same volume, at the same pressure, but more. This metal oxide framework is a structure which allows the atoms of the gas, not of liquid of the gas, to be pulled into place; as such they’re not knocking into other atoms and, therefore, you can get more of them in the same volume.

Chris - People talk of these as a bit like a molecular sieve, don’t they? You can imagine chicken wire at the molecular scale, where the wires link together you would have atoms of different types and it gives specific properties so you can have different gauges of your chicken wire and you can have different chemical properties. So in this context you’re saying you can use this to store gas? Presumably they’re choosing atoms that lock onto the gas you want to put into the cylinder very tightly and enable it to bond onto the walls?

Peter - That’s right. The framework size will be tuned to the type of… so if you’ve got a single say hydrogen atom, which is probably not used for they’re minute. But if you’ve got a complex - acetylene or something - which is very much longer, you’ll need larger pockets for these molecules to sit in.

Chris - Why is this a good thing? Does this mean what, we can get more gas into the cylinder so we need to spend less money on very dense, thick cylinders so you can have a gas at lower pressure? What’s the reason for this technology?

Peter - Yes, that’s part of it. You can, at the same pressure, have the same thickness of wall so you don’t have to increase the pressure, but it’s more to do with transport. It’s to do with the fact you can transport around more gas. Now there is two ends to the spectrum; one end is amazingly is ships. So you imagine there’s a lot of natural gas, which isn’t liquefied, that’s transported around the world. And the numbers they’re talking about are 14 times. If you can get 14 times more gas in a ship, that makes a huge difference, doesn’t it, in terms of cost. And at the other end is bottles say of something used in hospitals where you don’t have to replace the cylinder that often.

Chris - Thank you Peter! Peter Cowley - whom you can also catch talking about business and entrepreneurship on his Invested Investor podcast.

14:19 - Parker Solar Probe

Parker Solar Probe

with Nicky Fox, Johns Hopkins University

This week, a very special spacecraft is beginning an extraordinary journey into the heat of the Sun’s corona (or outer atmosphere). The Parker Solar Probe launched on August 12th and is setting off to uncover some of the mysteries of the hottest part of the Sun, and hopefully, won’t melt in the process. Katie Haylor has been finding out more…

Katie - On the 11th August, 2018 the Parker Solar Probe - 60 years in the making - older than NASA itself is set to launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida. It’s quite a small craft; imagine an hexagonal compartment about 1 by 1½ metres - that’s the main body where most of the scientific kit is housed. About 1½ metres above is the heat shield.

Nicky - It is made of a carbon-carbon composite. It’s very similar to a graphite epoxy that you might find in golf clubs or a nice tennis racket. And it’s a sandwich structure; there are two very thin face sheets and then there about 4½ inches of a carbon-carbon foam about 97 percent air when it’s here on Earth. And then on the very front surface of that we have a plasma sprayed alumina coating that actually reflects most of the sunlight. The front side of the heat shield will get to about 1400 degrees celsius, but the instruments on the main body of the spacecraft just a little bit above room temperature.

Katie - The mission's project scientist, Nicky Fox. So, equipped with this rather impressive shield, once in space the probe will journey through the Solar System using gravity assists from Venus to do a series of fly-bys through the Sun’s corona across the seven years of the mission focusing its orbit closer and closer to the Sun and getting to, at its closest point, a mere 3.8 million miles above the Sun’s surface. This probe will get closer than ever before to our Sun and will, hopefully, survive long enough to beam back data to us here on Earth. So why attempt something so daring? Well, there are a few mysteries about the corona that have been bothering scientists for decades. First up, the corona itself is about 300 times hotter than the surface of the Sun despite being further away from the heat source, which is rather puzzling…

Nicky - The other mystery is why it's accelerated so fast in this region. So where you see this incredible heating, the plasma itself gets energised and it does accelerate away from the Sun at supersonic speeds out and bathing all of the planets. It carries with it the Sun’s magnetic fields; so the Sun is rotating, and the magnetic field of the Sun is rotating with the Sun and all of that material is kind of stuck on those magnetic field lines. Where the plasma gets super-energised it is so energetic that it actually grabs the magnetic field of the Sun and pulls it away from the Sun with it as it streams out towards the edge of our Solar System. The Earth has a magnetic field and those two fields can interact, when the Solar wind arrives at the Earth, and cause large scale changes and it can lead to big space weather events. And by going and making these measurements in this region it will finally enable us to put the physics behind the drivers of the solar wind - the stuff that is coming and impacting our planet. It will make transformational improvements in our ability to predict the impact that the Sun has on our Earth every day.

Katie - So what kind of equipment is on board this probe, which is going to capture the information needed to answer these questions?

Nicky - I mentioned the magnetic field as being something that’s changing so we carry three magnetometers with us to make sure that we cover the full frequency range. Where there’s a magnetic field that's changing there’s an electric field that’s changing, so we carry antennas on the spacecraft and they will also measure plasma waves. And so when you have all these particles moving around they generate waves and the characteristic wave will tell us a lot about the physics that is going on. If we see one type of wave we know it’s likely to be one type of physics, etc.

Katie - The probe will also capture some key characteristics of the continually streaming Solar wind. Things like speed, temperature, composition and density, so scientists can learn more about the plasma close to the Sun…

Nicky - And then we also carry high energy particle detectors with us that measure those very high energy particles associated with those transients, so the flares, coronal mass ejection shocks in the solar wind. And then, last but not least, we have a white light imager that is taking images of, essentially, the Solar wind right in front of the spacecraft - so what the spacecraft is about the plough through - so that will help us to put into context all of these wonderful in-situ measurements that we’re making with the rest of the payload.

Katie - There are big expectations for this little craft. I asked Nicky about what challenges lay in store…

Nicky - We do have to worry, of course, about the heat, the dust. We have to keep our solar panels cool. Another really huge challenge: it takes light eight minutes to get from the Sun to the Earth so there’s no way we can "joystick" this mission. If anything goes wrong, she is totally programmed to figure out what it is that is going wrong and fix it on orbit. You’re sending a spacecraft into this very challenging environment and she’s very very small, but she’s very independent. It’s an amazing team that we have that have really put her through her paces. And it is rather like sending your kids to college; you do the best you can, you bring them up, and then you send them out into the world, and you just hope that they can take care of themselves...

Could animals speak?

with Jacob Dunn, Anglia Ruskin University

Here on the radio we certainly enjoy talking. And a new piece of research this week has revealed the parts of the brain that may have been key to this behaviour evolving. Georgia Mills has been investigating...

Georgia - Who hasn’t wanted to confer with cockatoos, banter with antelopes, or rabbit on at rabbits. But can any animals talk back?

Jacob - It kinda depends on what we mean by "talking"...

Georgia - That’s Dr Jacob Dunn, Director of the Behavioural Research Group at Anglia Ruskin University.

Jacob - There are other animals that can mimic speech sounds - famously a lot of birds do this like parrots, and budgies, and so on. They can make lots of different sounds; whether we think that cognitively they're using language in the same way that we are is a bit of a different question. But certainly, they can make complex speech sounds which sound very much like they’re talking.

Georgia - This mimicking has even been seen to some extent in seals, elephants, and killer whales. So what about our closest cousins - the primates?

Jacob - Well, this is where it gets really interesting, because the apes and the other primates, one would think, because they’re closely related to us and do lots of very clever things like using tools, one would think that they would have very advanced communication similar to our own. But when it comes to vocal communication, they seem to be really quite limited and they don’t use complex vocalisations in any similar way to the way that we use speech.

Georgia - So something quite distantly related like a parrot can mimic human speech and demand crackers, yet our closest relatives can’t despite the fact that all things point to them having a very similar vocal anatomy. So what’s going on?

Jacob - What people have said for a long time; in fact Darwin said this, he said “perhaps the brain is much more important in this regard.” What we went out to do was the first sort of large-scale comparative study looking at non-human primates, which make a range of different sounds, and saying okay, well they don’t make many different sounds, but there is a variation across different primate species in how many sounds they produce. So we carried out an analysis trying to compare that variation to brain architecture.

Georgia - How did you do that and what did you find?

Jacob - The brain data came from published data. There are large brain collections in different places around the world, and the information about the size of the brain, the weight of the brain, and then the various different structures within the brain are calculated through histology. So what that really means is that you’ve got, a bit like in a delicatessen in a supermarket, you put your brain through a slicer. You’ve got lots of very very thin slices of pastrami, and then you’re able to take images of each of these slices and, eventually, recreate a 3D model of the brain.

Georgia - Crucially you then don’t eat it afterwards!

Jacob - Then you don’t eat it afterwards. You’d probably get quite sick if you did! We took this data on the size of different structures of the brain across these different primate species and related it to the number of different vocalisations that they produce.

Georgia - What did you find?

Jacob - We found a very strong positive correlation between the number of different sounds primates produce and the relative size of their cortical association areas. The cortical association areas are important information centres in the brain. They receive the sensory input and they are a bit like a computer that decides what to do with that. We also went on to look at some other areas of the brain. What we found was that the hypoglossal nucleus, which is this little structure in the brain stem from which the nerve comes out and innervates the tongue, was found to be significantly bigger in apes than in other primates, as were the cortical association areas. So this might tell us a little bit about how, through human and hominin evolution, we evolved with time to grow smarter brains but also how that might have co-evolved with this particular part of the brain, which is innervating the tongue. And that might tell us something about how, eventually, in our primate ancestors, we achieved better control over the vocal apparatus as our brain was changing.

Georgia - But forget about finding out the answers to crucial questions on the origins of humanity. When are we going to get talking monkeys?

Jacob - The recent literature - a really great paper came out saying that the monkey vocal tract is "speech ready". What they argue is that the vocal tract of the macaque, which they looked at, is capable of moving in all the ways to be able to produce the key vowel sounds which are important for human speech. And therefore, if we were to stick a human brain on top of a macaque larynx, it ought to be able to speak!

Georgia - Monkey butlers.

Jacob - Exactly. And therefore, in the future, who knows exactly how this is all going to play out but, one way or another, there may be new techniques to be able to fiddle around with the brains of bio-med primates, which I would not be on board with I have to say, to begin to get them to produce language...

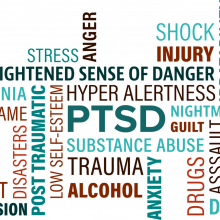

26:59 - What is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

What is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

with Jennifer Wild, University of Oxford; Malcolm Iliffe, former Sergeant, Coldstream Guards

What is PTSD? Georgia Mills talks to Oxford University clinical psychologist Jennifer Wild...

Jennifer - PTSD is a severe stress reaction. It develops after exposure to extreme trauma and it has a number of symptoms. The main symptoms that are quite disabling and troubling are what we call the “re-experiencing symptoms.” These are unwanted memories that come back to mind very frequently and are very distressing and take up a lot of attention and disrupt somebody’s day. There are also flashbacks, and when flashbacks occur it can make someone feel as though they’re back at the time of the trauma and it happening all over again. Nightmares are another form of re-experiencing symptoms and memories that wake people up in the middle of the night and are distressing, and usually people can’t get back to sleep afterwards. The next set of symptoms are the avoidance symptoms. This is avoiding reminders of the trauma. And the next category of symptoms are what we call negative alterations and cognition and mood. And what that really means are that after trauma, people either develop quite negative beliefs about themselves, or they may have had negative beliefs early but these get quite a lot stronger afterwards so they may feel and believe that they’re very worthless, for example. Then the final category of symptoms are the hyperarousal symptoms. So feeling hyper aroused, difficulty concentrating, difficulty sleeping, feeling very very on edge.

Georgia - What kind of a trauma could bring PTSD on?

Jennifer - Quite a broad range of trauma can trigger PTSD. A trauma such as a sexual assault, a physical assault, military trauma, bombing, terrorist attacks, the loss of a loved one by traumatic means.

Georgia - When someone develops PTSD, does a change happen in the brain that we can kind of "see"?

Jennifer - We know that, with trauma, stress hormones are released and they may affect the brain. They may make it difficult for the amygdala, which is our emotion centre in the brain, to dampen down an emotional response. So, in PTSD, we see this over-generalised sense of danger so lots of things feel very dangerous. And this could be because the amygdala, the emotion centre of the brain, isn’t well dampened-down in PTSD. So, after trauma, for some people, they’ll have a hypersensitive amygdala, which will make it very difficult to feel calm in response to a trauma reminder.

Georgia - How common is PTSD?

Jennifer - It’s quite a common disorder and what we call the “lifetime prevalence” is between seven and eight percent. So, seven or eight percent of people will have PTSD at some point in their life...

Some studies have estimated the lifetime risk for PTSD of up to 30% in veterans of certain wars. It can make transition from the military into what’s commonly dubbed "civvy street" much more challenging. Malcolm Iliffe, was a sergeant who served with the Coldstream Guards, a regiment that played a key part in the proceedings at the Battle of Waterloo...

Malcolm - Sometimes to be an ex-forces you think you’re alone a bit. We all seem to have slight problems. I mean I know I’ve got PTSD. It’s not the nicest of thing. It plays havoc with your life. I still can’t even hold hands with my wife, for instance, because I can’t let my guard down. It is horrible at times.

Sometimes to an ex forces it’s a lonely life after you leave. There’s ex-forces on the streets, there’s ex-forces in prisons, they’re in mental homes. And for somebody like myself I can go months without actually talking to anybody or going out. I feel safe in my own environment.

But I feel like now I want to go out and tell people. The experience I’ve had here it’s so hard to explain when you’ve actually found something from the period. The history of my regiment it like give you… it’s like an injection. It’s pumping something back into you. But just to come to Hougoumont for me is a big honour because I’m ex-Coldstream Guards.

My battalion was the gate; one of our sargeants shut the door and I think for any Coldstream to come here. It was such a big battle for us. I mean it must have been a hell of a feeling for them. They were surrounded on three sides, there was a fire fight going on, but you’re doing your job. They’ll have all been doing their job yeah, but everybody’s frightened. If anybody says to you in any interviews they weren’t frightened in any conflict, they’re lying.

You are frightened but you’re doing a job. You’ve been trained to do a job. They’d have been trained to put their musket balls in the barrels. They’d have been trained to fire back. No different than us changing a magazine on the rifles that I used when I was in. You’re doing a job.

Your colleague drops next to you; if he’s badly injured you try to do someert, if not, you just carry on. He’s another dead person; you’ve got to carry on. And there’s always that saying stand, stand, stand your ground, stand. Even in today’s warfare they stand.

The lads that were here in 1815 would have been exactly the same. They’d have been no different from me...

34:48 - Battlefield archaeology

Battlefield archaeology

with Tony Pollard, Professor of conflict history and archaeology, University of Glasgow; Hilary Harrison, Finds Officer, Waterloo Uncovered

So how are the Waterloo Uncovered teams doing the archaeology? Tony Pollard, from the University of Glasgow, has state of the art equipment which can scan the ground for magnetic anomalies. Georgia Mills heard how it works...

Tony - Basically what these allow us to do is to look for disturbances under the ground. If you dig a hole you will change the local magnetic field. If you light a fire you again, will create magnetic anomalies. If you dig a hole and backfill it with soil which then becomes wet, its resistance relative to the soil around it will be less. So all of these physical properties can be read and measured, and they create a map of disturbance that is invisible on the surface.

The thing is though you still have to do what we call “ground truthing” which is doing some ‘old school’ archaeology - dig a trench and see what the anomaly actually means, and we’re about to do some of that today. We’ve got two large anomalies just beyond the trees there in that field, which is just south of the south gate at Hougoumont and we’re going to see what they actually relate to. They could be any number of things.

Some of the first anomalies we looked at were brick kilns. They gave up high magnetic readings which suggest burning and, indeed, they related to the construction of the bricks, and those bricks were used to build the farm. So now we have the plan of genesis of Hougoumont which is really exciting.

Georgia - And as well as old fashioned digging, they’re also using metal detectors as the musket balls, weaponry, and parts of uniform were often metallic…

Tony - What we are looking for, at least in part, artifacts, objects that were dropped during the battle. So they may be musket balls that were fired, horseshoes, bits of broken weaponry…

Wow. look at that one, eh!

Georgia - These finds end up in the aptly named Finds Room...

Hilary - I’m Hilary Harrison. I am the Finds Officer for Waterloo Recovered. I have been on every dig that they’ve had here so this now my fifth dig out here. I did two in the first year.

You are in, at the moment, what we call the Finds Room. Everything that comes out of the trenches is brought into here. We then dry it all. We dry clean it,so we don’t wash anything because the majority of what we get is metallic and you never wash metal anyway, so everything is dry brushed.

Georgia - There’s this big white table in front of us full of mysterious items. Are these the finds that have been coming in? Can you tell me a bit about them?

Hilary - These are finds that have been coming in. What we have across here is an awful lot of iron nails, musket balls which have been impacted so they’ve actually been fired.

Georgia - Are those the sort of flatter circles?

Hilary - These are the flattened ones. We have an impacted one here.

Georgia - Wow! So it’s really gone ‘splat’ hasn’t it?

Hilary - Oh, this one’s hit something really solid. Get some mud out of the back of it… that’s the sounds of me carefully digging around the entire musket ball to get the mud out of the back of it so we can see what it looks like. This has gone splat against something and because of the speed that’s it’s travelling at, and because it is a soft metal, when it goes splat it doesn’t stay flat. If you think of a drop of water hitting something it hits and then comes back a little bit, and because this is solid you then get a hollow in the middle and a hollow round the outside where it’s gone splat and bounced back.

Georgia - So you can really tell the ones that have hit something.

Hilary - This one I think has probably hit a wall because you’ve got little bits of red in it, so you’ve got little bits of brick dust in it. Each musket ball has its own tale to tell.

Now what else have we got here. We’ve got mysteries on here; I mean I’m not sure what that is but it’s a little decorative piece probably off the end of a rod of some sort.

Georgia - Like a flag pole?

Hilary - A flag pole. It could be off any one of a number of things but that’s sort a little decorative thing of some sort. We’ve got some coins here; lots of musket balls; indeterminate pieces of metal. I think that’s a handle. That might well be a button, possibly English, plain, it doesn’t weigh very much. The French ones had bone and wood inside them so they did tend to weigh a little bit more.

Georgia - There’s about a hundred things just on this table so there’s a lot to get through.

Hilary - Oh yes! We will have dealt with over a thousand finds and there’s two of us who have got experience in the room. We’ve got two people who have come in just this week and last week so their learning and working really help. We’ve got Malcolm who’s just come in for today.

Malcolm - Yes.

Hilary - And he’s thoroughly enjoying himself.

Georgia - Yeah?

Malcolm - Yeah. I’m finding lots of things. I mean I’ve picked lots of these things up with the detectors. Now, I’m actually cleaning them and finding out what they are. It’s just an absolutely fantastic feeling to know when the dates are, where they’ve come from, and everything else.

Georgia - But there’s something that conspicuously has not been found. Over 50,000 people died at Waterloo…

Tony - We haven’t come across any graves. We’ve not been deliberately hunting graves but, obviously, with a battle site it’s an issue. And we have various paintings of the time of bodies being buried here at Hougoumont, and one instance here in the car park we investigated the site of one of these paintings. So two years ago we had look here, and we got the machine, and then we broke out the tarmac. But, at the end of along project, we came up with a single finger bone.

Georgia - Tony Pollard. So where are all the bodies?

40:55 - Mysteries of Waterloo

Mysteries of Waterloo

with Tony Pollard, University of Glasgow; Phil Harding, Time Team Archaeologist

Napoleon’s forces were advancing towards Brussels. Wellington's smaller army had to hold them off, knowing Prussian reinforcements were on their way. The fighting was fierce at Hougoumont farm, with the allied forces trying to hold off a French onslaught; the field outside the compounds became suitably-dubbed “the killing zone”. Meanwhile, outside the field, there were infantry, cavalry, cannons and muskets all firing salvoes into each other. It was a mess of blood and musket smoke. Over 50 000 people are estimated to have died. So where are their remains? Speaking with Georgia Mills, University of Glasgow archaeologist Tony Pollard...

Tony - There are several theories that could be drawn from that. One is that in the decades following the battle, the mass graves at Waterloo and other battlefields from the Napoleonic era across Europe were actually exploited for the human bone because, prior to the modern phosphates industry, bone meal was a very important fertilizer along with things like bird poo. And it was a bit of an industry, so teams would go out scouring these big battlefields and, no doubt, asking the locals where the big graves where that would be worth their while literally quarrying. Given that this one is represented in a painting it’s highly likely that even 20 years later it would be remembered and they may well have come here and dug out the bones and shipped them back to Hull in England where they’re ground up and spread on the fields. Yeah - unpleasant. These were hard times. The idea that people are coming here and moving those bodies, the evidence is here to suggest that might be the case because we just don’t have them.

Georgia - Now there is a less gruesome theory, and that’s that there is a war grave but it’s just somewhere no-one’s thought to look yet. And the team are keen to emphasise that they’re not actively looking for human remains, but there are still lots of items telling the story of the battle being unearthed minute by minute. I paid a visit to one of the trenches from inside the compound…

Paul - It’s quite exciting actually, yeah.

Georgia - That voice is Paul who was a soldier for 24 years and is now very well acquainted with an archaeologist's trowel. What’s that?

Paul - I don’t know. I really don’t know! It’s just trying to add to the stories eh, that’s what we want to do. And as I soldier I get it, you want to add to the soldier’s story. The (02.36) history, these voices, unheard voices, are they coming back to life again or in my mind they are. They’re coming back to life. It’s given them that opportunity.

Phil, there’s loads of stuff coming up. I’m all excited.

Phil - He’s found a buckle, eh.

Georgia - That laugh you can hear is the trench supervisor.

Phil - Well, I’m Phil, Phil Harding. I suppose everybody knows me off the the tele programme Time Team.

Georgia - It’s Phil’s fourth year with Waterloo Uncovered.

Phil - They aint sacked me yet.

Georgia - I sat down with Phil to find out about this trench inside the compound and what they’d been finding…

Phil - well, where we’re conducting this interview would have been an enormous barn at the time of the Battle of Waterloo and we know the barn was set fire at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, and it is a crucial part of the battle. We are as close as we can get to the north gate and, if you’re a Coldstream Guardsman the north gate is holy ground. They famously shut the north gate at the Battle of Waterloo.

Georgia - Is that the gate we’re looking at there?

Phil - That is the gate that’s there. I mean it’s a modern reconstruction of course. But had the French broken in the could have taken Hougoumont farm, and if Hougoumont farm had have fallen then that would have very very strongly weakened Wellington’s right flank. So the closing of it really was a very very important part of the battle.

One of the great discoveries of what we’ve been doing is masses and masses of grey slate. Now, you look at all the reconstructions and they all tend to show red ceramic tiles and, apparently, some people even think the barns were thatched. Absolute rubbish!

In my humble opinion it’s a slate roof and I believe the whole of Hougoumont farm would have been slate roofed and that’s a brand new discovery.

Georgia - What have you found so far?

Phil - We have exposed vast areas of slates and they, we believe, are part of that roof that fell in at 3 o’clock on June 18th, 1815. And believe you me, as an archaeologist, if you can deal with something in spans of 50 years plus or minus you’re probably doing quite well. But when you can actually pinpoint the day and the actual time, that is something else.

Georgia - We know that it’s hard to think of when we’re sitting here; it’s very peaceful, it’s a lovely bright sunny day but this would have been a massive barn in a battle, that was on fire and collapsed?

Phil - That’s the awful thing. I mean, it’s the obvious place for people that were wounded to crawl away for a little bit of a safeguard. And, of course, when you’re in a building and you watch the roof set fire and you haven’t got the strength or the energy to make it back out of the building and there’s smoke everywhere, you probably can’t even find the doors.

Georgia - What is it like? You’ve been doing this project for four years but you’ve done all kinds of archaeology, what is it like working with this team of veterans?

Phil - Oh it’s great, you know. I’ve been an archaeologist all my life; that’s what I was put on this planet to be, sadly I suppose. It’s nice to have a bit of purpose in it really? You’re only here for a short while I might as well make use of the time. And so I’ve always wanted to be a an archaeologist and so I’ve been happy with my life.

I get so sort of blinkered, so narrow minded about archaeology being the be all and end all of it that is kind of nice to be able to sit back at times and reflect that, actually, it can be beneficial. Not just in finding stuff and understanding about the past but actually serving people who are alive now and giving them a break, and giving them fresh ideas and fresh insights and all the rest of it. It’s very very rewarding and it’s really an accolade that archaeology can be one of those things that can help benefit people. I’m a dry old stick, you know. I’ve been doing archaeology a long time now. But I still get a buzz of finding stuff and, of course, these guys they’re finding stuff for the first time and they’re getting that buzz that I’ve had all my life. I’m sure you’d agree, you were here when Paul found that buckle. There he is, he’s a grown man, but he was behaving like a five year old schoolchild.

Georgia - I was that excited as well though.

Phil - Yes, well you were just behaving like a three year old.

Georgia - I’m going to cut that out of the tape. No-one needs to know that!

And the project ideally works two ways. As well as providing therapy, having people who’ve seen battle can actually provide unique insights into what might have happened. Tony Pollard again…

Tony - There’s the old phrase they’ve seen the elephant, they’ve been in battle. None of us archaeologists we’ve not experienced battle. And to have people here who’ve been through that incredibly unique process is very rewarding. One example is the walled compounds here. They’ve stormed walls, they’ve defended walls and every now and again one of them will look through the loophole in the wall go well, that’s too low for me that field of fire isn’t great. It makes you step back and draw breath really because it is an amazing connection that reaches out across the centuries to the time of the battle. I think we’re very privileged to have these people here.

51:15 - Archaeology as a therapy

Archaeology as a therapy

with Jennifer Wild, University of Oxford

How effective can archaeology be as a therapy for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)? The University of Oxford’s Jennifer Wild gave her opinion to Georgia Mills...

Jennifer - PTSD in and of itself has a natural recovery. So unlike other psychiatric disorders over time, within a five year time period, the majority of people will recover from PTSD, so about 60 percent of people. However, whilst that sounds optimistic; one it means that 40 percent of people won’t, and two that means for a five year period people are still suffering from their life being turned upside down - they’re relationships falling apart, being unable to work.

So whilst PTSD does have a natural recovery, it is important to offer treatment early on. The best treatment for PTSD is trauma focused cognitive behavioural therapy, which focuses on the trauma and helping the person to pull apart the trauma in a lot of detail and start to think about it differently so that, with the help of a therapist, the person can break the link between the past and the present and overcome the debilitating symptoms.

So you think archaeology is a novel form of treating PTSD is an exciting idea. We’ve been talking about trauma focussed cognitive therapy and one of the components of that treatment is actually going back to the site of the trauma where it happened. This is really important because often people have beliefs or feeling like the site of the trauma is frozen in time, and it hasn’t changed, and it’s completely dangerous and overwhelming and I won’t be able to cope if I go back.

The therapist would often, as much as possible, go back to the site of the trauma either in person or, if that’s not possible because it’s happened in another country, by Google Street View. We would look at it on computer together and look at what’s different now and often the client realises that the site has moved on and it no longer contains all of the dangerous, traumatic features that were there when the person went through the trauma.

In terms of veterans, using archaeology to come to terms with PTSD as a way forward this is novel and potentially could be really helpful because it’s not exactly their trauma site, but there will be reminders of their trauma when they’re there. And if they can focus on what’s different and what’s helpful, and what people did that was helpful who were involved in that particular battle, then this may help them to see the trauma site in a different way and thing about, and reflect on their own trauma site in a different way which may help to reduce some of those memory symptoms that they’ve been having.

Midge - My names Midge Spencer. I’m a British Army Veteran. I served for 25 years in the British Army as a combat medical technician. I started to have mental health problems and I’d had problems over the years and didn’t really understand what was happening and didn’t say anything about it because it’s not a good thing for your promotion and such like, you know to admit that you might have some mental health problems. So I kept it to myself really and I was then basically isolating myself from the world. I didn’t go out, I didn’t see anybody but my wife. If somebody phoned the house and I didn’t recognise the number I wouldn’t answer it.

After my first year here I mean it just gave me an interest back in life really. So talking to the academics while I was here I told them that I’d dropped out of my Masters degree and I felt a failure as a result of that which, of course, adds to the cycle of depression and negative thinking. They encouraged me to sort of try and re-engage with it. Several months later I contacted my old supervisor to see if I could get back into it to just finish my dissertation because that’s all I needed to do, and they’ve made it so that I can do that. So I’m working on that now and I have to submit my dissertation by the end of January next year - 2019.

Georgia - What about the project do you think that... or have you taken a personal benefit from it?

Midge - I’ve taken a personal benefit because it gave me back an interest in myself, an interest in life in general, a sense of purpose. It brought me back into engagement with fellow veterans, people who felt the same way that I did. I mean before this I sat at home thinking I’m the only one who feels this way and, of course, I’m not. But because I didn’t go out and engage with others I didn’t speak to anybody else with similar circumstances.

This is my third time but already, just at the beginning of week two, I can see changes in some of the guys from when they first arrived last weekend. I can already see them coming out of themselves. And it changed my life more than I can really explain.

Related Content

- Previous Testing for Tuberculosis

- Next How did early life evolve?

Comments

Add a comment