Science meets MasterChef!

The Naked Scientists are hosting their very own dinner party, and the guests include a master distiller, a MasterChef finalist and a master of chocolate, all on hand to help reveal the science behind the perfect dinner party. Plus, the world's fastest supercomputer boots up in China and news of why itchy mosquito bites are more likely to infect.

In this episode

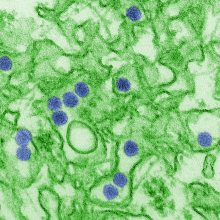

01:02 - Itchy mosquito bites boost infection

Itchy mosquito bites boost infection

with Clive McKimmie, University of Leeds

The itchiness of a mosquito bite isn't just an aggravation: scientists have discovered that the inflammation that makes you want to scratch, dramatically boosts the infection rate for viruses like Zika, dengue and yellow fever, that the insects can carry. Clive McKimmie is at the University of Leeds, and explained his research to Chris Smith...

Clive - When mosquitoes bite you, what they're doing is they're trying to take a blood meal from your skin but, in the process, are spitting out saliva into your skin. This rather disgusting to think about, but this saliva actually contains a lot of disease causing viruses and some of these are quite well known such as the zika virus, dengue virus, and chikungunya and together that infects maybe several hundred million people each year. What we do know is that the mosquito bite somehow tends to be helping virus infection and giving it a boost.

Chris - So, over and above the physical fact you've got this flying hypodermic needle that comes along and injects you with virus particles, there is an effect in addition to just putting the virus into you whereby the mosquito increases your likelihood of catching whatever it happens to be carrying itself?

Clive - That's it. We actually know very little really about what happens during the early stages of infection, and what we've done in our recent paper is to show how - what we call the mechanistic basis - by which the mosquito bite really seems to help the virus infection along.

Chris - And how does it, what does it do?

Clive - There's two things going in here. Firstly you have a bite and I think anyone who's been bitten by a mosquito knows what that's like. You get a horrible red swelling, there's some what we call inflammation. What your body is doing actually is perfectly normal. Whenever you get injured or cut, what happens is your immune cells, these are the cells that help to defend your body against infection, they rush to the site of the damage which is the mosquito bite in this case and they're trying to stop any infection that's there, but actually what happens is quite strange. These immune cells that we call leukocytes actually seem to get infected by the virus if it's present, and the virus takes over these cells and uses to replicate so there's more and more copies of the virus in your skin. So if you can stop those cells coming into the bite site, then you can also stop the virus from getting that extra boost.

Chris - Does this mean then we might have a new way of arresting the spread of some of these viral agents so that you might, for instance, have something that you could rub on which would cut down the risk of a virus infecting you via that route?

Clive - Well, we've certainly shown in the laboratory setting where everything's very well controlled that if you can stop that bite inflammation, then you can stop the virus from causing disease. Now the next step, obviously, is to work out how best we can do that before we could even begin to imagine doing any studies in humans. Because I think we have to be very careful about any form of immune suppression because that can actually be quite dangerous, even if it is a topical cream. We're very keen now that the next step is to say can we use this knowledge to stop the virus from spreading by targeting the bite inflammation, and that's particularly exciting because it's common to a lot of these infections. Whether it's zika or dengue, they're all transmitted by the same mosquito into the bite site.

Chris - That was going to be my next question which is, is this generalisable? Viruses spread by mosquitoes and there are many types of them, do they all exploit this mechanism?

Clive - Well we've looked at two very genetically distinct viruses. These are viruses that have nothing in common with each other, but what they do have in common is they're spread by the same mosquito. We showed that in this paper that this mechanism, this way by which the bite boosts the infection, does seem to be the same. And there's actually a paper out just this week from another group in America which is working on dengue, and they find something similar where mosquito saliva is boosting the dengue infection.

Chris - Is there any evidence that, in turn, the virus is manipulating the mosquito for instance, to make it's saliva more inflammatory so that the mosquito makes your bites itch more, so more immune cells are effectively coming and, therefore, you increase even further the likelihood you'll pick up that infection?

Clive - Well that sounds like an excellent question. I don't think there's any data out on that just yet. There is some data which shows that viruses do change what genes and proteins are made by the mosquito but we have yet to look whether that's actually directly related to how itchy or how inflamed a bit can get, but it's certainly a very good question.

Chris - Clive McKimmie, and that discovery was published in the journal Immunity.

05:49 - Abortions boosted by Zika warnings

Abortions boosted by Zika warnings

with Catherine Aiken, Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge

Fears about the dangers of Zika infection in pregnancy are fuelling a dramatic  rise in illegal abortions in Latin American countries, a new study has shown. Because the practice is against the law in these places, women are feeling compelled to explore unsafe "back street" options that can place their health in serious jeopardy. And, ironically, this is happening in response to public health measures designed to educate people about the Zika threat... Catherine Aiken is one of the authors of the study and a women's health doctor at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, and she explained the problem to Chris Smith...

rise in illegal abortions in Latin American countries, a new study has shown. Because the practice is against the law in these places, women are feeling compelled to explore unsafe "back street" options that can place their health in serious jeopardy. And, ironically, this is happening in response to public health measures designed to educate people about the Zika threat... Catherine Aiken is one of the authors of the study and a women's health doctor at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, and she explained the problem to Chris Smith...

Catherine - There's been a huge surge in demand abortion across Latin America countries where government and health organisations have issued warnings about Zika virus, and what we see is it's been panicking women. They've been feeling that they have to take matters into their own hands to procure abortion in settings where it isn't legal to access it.

Chris - How big is that surge in demand?

Catherine - In the highest countries that we've seen is up to 150% increase.

Chris - And you know this how?

Catherine - We know this because we partnered with a non-profit, non-governmental organisation called Women on Web. They're an organisation to provide telemedicine abortion all over the world but particularly in settings where legal abortion is restricted or not available. They do online consultations with women and they either provide abortion drugs directly or they give women advice on where they can be reliably obtained within their own settings. And were were very fortunate to obtain their data to model how demand for abortion in various regions across Latin America has been over the last five years, and then to study it since Zika virus has become an issue in these places to determine the effect, not only on Zika but also these public health warnings.

Chris - And, of course, if one worries people into putting themselves in the position of seeking an illegal abortion, they're potentially putting themselves in the hands of unscrupulous operators and much worse health outcomes than anything Zika might throw at them?

Catherine - Quite right. So Women on Web's method of telemedicine abortion has been shown to be very safe, but it's only available to women who have access to the internet and it's only available to women who know about it. There are many, many other women who may well be driven to other much less safe methods of illegal abortion and we're very worried about their health.

Chris - Rather than pursuing abortion, are we not also really in need of a decent test that will tell a woman whether or not she has Zika and, more importantly, if she has whether or not her baby's at risk?

Catherine - Absolutely, that would be the very, very high priority. But we're in a situation at the minute where we don't have that, where we're very unlikely to have that because the babies that we're seeing now, their problems may not manifest for many years, and we may not be able to develop something like that within the timescale that these women need it. A very neglected part of this whole story and the whole epidemic is what's actually happening to the women who are right now facing the day-to-day reality of pregnancies that they can't prevent because contraception access is also limited, and that they can't do anything about and that's a very frightening place for them to be. And one of the main things we wanted to do from our work was to give them a voice in the world's media.

Chris - So, put their thoughts into a few words that you would have said to the politicians in these countries. What's your message to them?

Catherine - My message would be that a public health warning on which people have no means to act and no means to help themselves, is a hollow and empty message that actually harms your population's health rather than improves it.

09:46 - New Chinese supercomputer

New Chinese supercomputer

with Peter Cowley, Angel Investors

China made history this week, when their super computer Sunway TaihuLight  was announced as the fastest in the world, and China can now claim more spots in the world's top 500 fastest supercomputers than the USA. Naked Scientist "techspert" Peter Cowley was on hand to take Georgia Mills through this 'super-development'.

was announced as the fastest in the world, and China can now claim more spots in the world's top 500 fastest supercomputers than the USA. Naked Scientist "techspert" Peter Cowley was on hand to take Georgia Mills through this 'super-development'.

Peter - Super's probably not the right term. I can imagine back in '76 when it was first used, then super made sense but it should be sort of hyper-ultra. The speed increase has been dramatic since then, like all computing power. So, for instance, the 1976 Cray, which probably cost many millions of pounds, is actually the first supercomputer which is actually 15 times slower than my watch on my wrist and 400 times slower than my phone. In the meantime, in the sort of 40 years since that happened up to the latest Chinese one we're going to talk about in a minute, they've been through all kinds of iterations, including one USAF (United States Air Force) computer that is 1,760 Playstation 3 consoles connected together. So a supercomputer is basically something that's processing very, very, very rapidly.

Georgia - So how did this new computer, Sunway TaihuLight, top this list?

Peter - Well the Chinese are actually number two as well, so they were obviously number one a few years ago. So about three years ago they must have said we're going to start to design a much faster computer and, unlike almost all the other ones in the top 500, which is a list that's published which will mostly use intel processes which are used in many of our PCs, they design their own silicon on that. So they've got something that's actually got 10 million separate processes in it. It's got 1.3 million gigabytes of memory - unbelievable. It processes almost a hundred million billion floating point operations a second. Absolutely, massively first.

Georgia - And floating point operations, what are they?

Peter - Floating point operations. If you multiply to long numbers together, that's floating point as opposed to fixed point and they're actually, interestingly called flops. They talk about petaflops and gigaflops and teraflops, so this computer is a 93 petaflop speed.

Georgia - That's a very floppy computer. So what does it actually do?

Peter - It's used for parallel processing - very important it paralleling processing vast amounts of data. So, weather prediction, flow around aircraft for design purposes, possibly for military applications I suspect, drug research, computer aided engineering, oil prospecting, etc., etc. So it's all to do with processing simultaneously vast amounts of data.

Georgia - It sounds pretty useful, so what makes them hard to make?

Peter - Obviously cost. I mean this one in China apparently cost 270 million dollars. They take a lot of power - 15 megawatts this thing takes and probably another 25 megawatts to cool it down, and software. You need some specialised software which will load huge amounts of data and run it in parallel and then pull the data back again for results.

Georgia - How big are these?

Peter - They are huge. I mean, if you compare it with my watch. It's 25 times faster, my watch, than the one originally but that is 40 years on. This thing, I say, probably takes up 200-250 square metres of floor space.

Georgia - Wow, incredible! This top 500 list, does the U.K. have any supercomputers on it?

Peter - Yes. It has slightly less than it did in 1996 but it does actually have 11. The two that are around about the 15/16 mark are Crays, which is an American manufacturer that's been around for many years , used by the Met Office for weather prediction. But the Met Office is actually buying a new one at the moment that will cost 100 million pounds. And to partly answer your question earlier on it actually weighs 140 tons, has got half a million cores, which is still 20 times less than the Chinese one but it's only 5 times slower so 16 petaflops per second.

14:02 - Myth: Chewing gum sticks inside you

Myth: Chewing gum sticks inside you

with Kat Arney, Naked Scientists

This week Kat's been getting her teeth into a sticky subject for her  mythconception...

mythconception...

Kat:: Are you a fan of chewing gum? I love the stuff and get through several boxes of peppermint gum every week. But I'm always careful to dispose of it carefully in the bin, and never swallow it, because I've heard the stories that it can stay in your gut for up to seven years. It certainly persists on pavements, desks and pretty much everywhere else people without good gum etiquette care to stick it. Flagrantly disregarding this advice, Naked Scientist Georgia's sister apparently swallowed a meter-long stick of chewing gum when she was six. So was it still working its way through her system when she hit her teenage years?

Well, luckily for Georgia's sister - and presumably her panicked parents - this is a myth. So what's the real story?

As the name suggests, chewing gum is designed to resist being broken down by the normal processes by which we digest our food - the first one of these being chewing. Because it's made of a base containing stretchy polymers, resins and other non-digestible components, chewing gum doesn't break down no matter how hard we mash it in our mouths. So it's pretty sturdy stuff. It's also resistant to the strongly acidic conditions in the stomach, passing through into the intestines in the same state it came in.

But once it gets there, it continues on its journey back to the outside world in the same way as the rest of our food, although possibly a bit slower than might be expected. In fact, gastroenterologists say that although they can sometimes see evidence of gum in people's guts when they're having a look in there, there's nothing that looks like it's more than a week old. This isn't unexpected - it's exactly the same for other non-food objects that get accidentally swallowed, including small coins or plastic toys, and even false teeth that mistakenly go down a grown-up's guts. We do swallow undigestible objects from time to time, especially kids, and unless they're particularly big or magnetic or batteries, nature usually takes its course and they'll eventually come out the other end.

There are a couple of reasons that the myth around chewing gum's longevity in the gut has sprung up. For a start, it's clearly not food - it doesn't break down in our mouths like normal chow, so we think we shouldn't swallow it. Then there are some published case studies, like the children who swallowed chewing gum every day for several years, and ended up having to have a large toffee-like trails of the stuff surgically removed from their intestines. Even more concerningly, in some cases the gum had collected other solid swallowed objects, such as coins or sunflowers seeds, adding to the problem. So it's still much better to spit rather than swallow your gum, especially if you're a daily chewer.

However, there are a few things that are hard to swallow. Pairs of magnets can pinch bits of the intestines together, leading to major problems, and it's also very bad to swallow batteries. And there's also an indigestible substance that does hang around in the guts for a long time, and that's hair. People with a compulsion to pull out and eat their own hair can end up with Rapunzel syndrome - a large hairball, known as a bezoar, trapped in their intestine that needs to be surgically removed. So that's definitely not a good idea. But humans have chewed gum - or at least stretchy tree resin and other indigestible plant matter, or even tar - for thousands of years. And although it's not a good idea to swallow it day after day, the occasional accidental swallow won't leave you with an unwanted intestinal visitor for years on end.

17:43 - Shark-proof wetsuit!

Shark-proof wetsuit!

with Jamie Oliver, Sea Life London Aquarium, Professor Shaun Collin, University of Western Australia

This week is Shark Week: an annual celebration of these charismatic swimmers whose numbers have dropped dramatically owing to human activity. So how can we better share the ocean? Georgia Mills has been investigating our relationship with these fearsome fish...

whose numbers have dropped dramatically owing to human activity. So how can we better share the ocean? Georgia Mills has been investigating our relationship with these fearsome fish...

Georgia - We are obsessed with having sharks on our screens. There's mega shark versus giant octopus, a film called Sharknado and, obviously, Jaws. And this week is actually known as Shark Week in American with a whole channel devoting their output to shark documentaries but off the screen in real life our relationship with these fish is less than perfect. Shark attacks can stir up tremendous fear and shark numbers are dwindling due to human activity. To find out more about how our relationship could maybe improve, I went to meet Jamie Oliver, Senior Curator at Sea Life London Aquarium and also got to see some of these fish face to face...

Jamie - So we have several species of shark. We've got this one coming towards us now called a Brown shark, also known as a Sandbar shark. You can see it's got a real classic shark shape - a nice large dorsal fin. And just behind it there we've got a Sand Tiger shark...

Georgia - Oh he's a big fellow, isn't he?

Jamie - He is. He's one of our biggest sharks at around 10 feet long - really beautiful animal actually. Actually quite harmless but they have this sort of fierce look about them because they're always bearing their teeth, you can always see their teeth. A lot of sharks hide their teeth, you can't see them when they're swimming around but the Sand Tiger's always got their teeth on show and it looks pretty awesome.

Georgia - Awesome indeed! But also very noisy so we nipped behind the scenes where I asked Jamie why sharks had such a fearsome reputation?

Jamie - There is a certain amount of misunderstanding when it comes to sharks. They're not really these dangerous predators, certainly towards humans, that we think they are. And the media do like to shout about it whenever there's a shark bite or a shark injury because it can be quite intensive in terms of injury. However, for the most part, they need our respect, they need our care, our love because they're really endangered in many parts of the world.

Georgia - Shark attacks may be extremely rare (there is only about 70 a year), but there's still pressure to cull them in popular surfing spots like Australia. But perhaps there's a way to make sure people and sharks can share the oceans. Professor Shaun Collin at the University of Western Australia has teamed up with Shark Mitigation Systems, and they're using their knowledge of shark biology to design a range of so-called shark proof wetsuits. I went to visit Shaun to have a look at some of these designs, the first of which was a funky blue and teal pattern, and asked him about how they're going about designing these wetsuits?

Shaun - So our approach was to look at the visual system. Firstly whether sharks can see in colour and, unlike most vertebrates, sharks don't see in colour, they're in fact colour blind. So contrast is actually more important to them in finding prey than colour is. So we used that information and, actually, took a lot of light measurements within the water off the coast of W.A. and tried to work towards a way of camouflaging the silhouette, or the high contrast boundary produced by a human in the water, which generally would be dressed in say a black wetsuit, for instance, which is the predominant neoprene colour.

So with reflectance measurements of different materials and different colours, and knowledge about the light environment that the animals live in, we were able to model and construct the optimal camouflage pattern that could be put onto a wetsuit to camouflage the wearer at different depths. Whether it be near the surface, halfway down or even at quite deep depths so thereby potentially helping surfers versus divers which would go deeper, so that's two of the designs you can see here. These are camouflaged wetsuits of slightly bluey-green tinges but, of course, this would be seen as shades of grey by the shark, not the colour that we in fact see them.

Georgia - If these two wetsuits works on camouflage, there's one on the end there that's got these white stripes across a very dark blue background. This doesn't look very camouflaging to me. Does this work in a different way?

Shaun - It certainly does, yes. The other design is quite the opposite, it's actually a very high contrast presentation where it's black or blue with intermittent stripes of high contrast and low contrast. And yes this will, in fact, make the wearer more obvious to a shark and will, hopefully, elicit the same behaviour but for a different reason. The different reason being that most sharks do not like striped patterns, as in they see striped patterns as being a deterrent, and indicator of something venomous. Normally animals avoid such patterns in nature and there's lots of examples of how that works with sea snakes and various other animals that are also striped. We have this conspicuous pattern that we've looked at and the banding periodicity, if you like, is governed again by our research on the visual acuity of sharks, so we've actually assessed what their spatial resolving power is. The patterns are actually designed to be obvious at a certain distance to a range of different predatory sharks.

Georgia - Well they haven't been able to tests these wetsuits on human subjects. There are obviously some ethical issues there. Shaun and his team have been using barrels instead and, hopefully, it won't be too long before they have some results out. So, if you're a surfer, watch this space. And, if science can help us to avoid shark attacks, can it also help us to conserve them? Because despite being more ancient than the dinosaurs, many species of shark are in real danger of extinction. Back to Jamie at Sea Life...

Jamie - One of the big factors is overfishing for their fins. There's a lot of sharks taken out with estimates between 20 and 70 million sharks per year taken from the sea. That's just not sustainable for a species that's slow to reproduce and that's having a devastating effect and, for many of those sharks, all that's used is the actual fin in shark fin soup, which is a tasteless broth really that has no real need for the shark fin anyway. There's artificial versions out there now but it continues to be a very popular dish in certain parts of the world.

Georgia - So what kind of things are being done to try and protect sharks?

Jamie - Many things. Certain governments are trying to create marine protected areas where fishing is banned. Here we're trying to educate all of our guests that come through the door and inspire them to go away and campaign, and sign petitions, and get out there and really shout about these creature, and really care for them.

Georgia - And just don't order the shark fin soup?

Jamie - Absolutely!. Don't go anywhere near it!

27:04 - Ant-flavoured gin

Ant-flavoured gin

with Will Lowe, Cambridge Distillery

No dinner party would be complete without some apéritifs to wet the appetite.  Before mixing up some gin and tonics, Chris Smith caught up with Will Lowe, Master Distiller of the Cambridge Distillery, who explained a little bit about the science of distilling gin, and how ants are providing him with funky new flavours...

Before mixing up some gin and tonics, Chris Smith caught up with Will Lowe, Master Distiller of the Cambridge Distillery, who explained a little bit about the science of distilling gin, and how ants are providing him with funky new flavours...

Will - So the Cambridge distillery is a unique distillery. We focus mainly on the production of gins but the way we make gin is different to pretty much everybody else in the world makes gin.

Chris - Can you just explain actually what is gin because I know I like it, I know how to drink it but I've no idea really what it is and what goes into it? I know it's got something to do with juniper.

Will - Sure and that's the start point really. Gin is just a spirit which is predominantly juniper flavoured but the way that that flavour gets there is very important. So the way most people gin is you start effectively with a very large pot, fill that with a neutral alcohol, and then add your juniper to that along with other botanical ingredients. Then you boil all that up, collect the vapour that results, condense that back into a liquid - that's gin. But that's not how we do it...

At the Cambridge distillery we take the observation that not all ingredients like to be boiled at the same temperature. In fact, some don't like to be boiled at all so we separate all the ingredients out and apply vacuum distillation. This allows us to reduce boiling temperatures so, in the case of things that are more delicate, cucumber rose for example, instead of increasing the temperature we simply drop the pressure right down so we can just lift the flavour off.

Chris - So instead of actually boiling up this giant stew and keeping the vapour and chucking the stew residue away, you're actually saying we can boil things off at a much lower temperature and, therefore, we may not get this deleterious, destructive effect on some of these more delicate ingredients? You can get them into the final product rather than just boiling them away?

Will - Yes, that's exactly the principle. So instead of having one big pot, we've got lots and lots of little individual chambers. We control the boiling point because of the pressure (different temperature in each case), so much lower temperatures for the much more delicate flavours.

Chris - Tell us about how you actually blend a gin or what is the anatomy of a good gin if you like?

Will - I like to think of a gin as having base notes, heart notes and top notes. This is something that really brushes shoulders with the perfume industry in many ways.

So with base notes for example, the key base note here will always be juniper. I've got some here for you to try actually. This is a juniper distillate so if you taste that you'll notice it's base notes typically tends to be characterised by being relatively bold flavours but relatively simple flavours.

Chris - I'll give this a try. So this is just a clear colourless liquid... It just actually tastes like cheap gin if I'm honest. It's just literally got that flavour of gin but just tastes like vodka and some junipery flavour.

Will - Yes. That is gin without its clothes on. That's a naked gin for a naked scientist. Where the character comes in, that's where we add a heart note. So at this point it's useful to understand a bit about how flavour actually works. Flavour being a combination of your sense of taste, which is what happens in your mouth. The way you have sweet, sour, bitter, acidity and umami and then you've got smell so olfaction. There are two routes to that, one through your nose so smelling as most people would call it but also orthonasal olfaction as we call it, and then backwards through the back of your throat, which is retronasal olfaction, and these interact very differently. A way of demonstrating this - I've got a spirit here that I'll put into a pipette and ask you if you can to put it into your mouth but with your nose held. Do you want me to hold your microphone?

Chris - You hold my microphone so I'm going to hold this pipette, I'm going to hold my nose and squirt this in my mouth...

Will - There you are. Now try and swallow with your nose still held.

Chris - Okay done that.

Will - You taste almost nothing and then when you release your nose... breath in and out.

Chris - Ohh. Oh it's a beautiful lemony flavour. Do you know I used to do the same thing with brussel sprouts when I was at school because I hated them, and I found if I held my nose I didn't have to taste them. That's the same principle?

Will - Exactly the same. By cutting off that access to retronasal olfaction, you can really dampen the flavour right down or the opposite as we just saw in there.

Chris - How does this apply to gin though?

Will - We use a heart note as something that you can identify by ortho and retronasally, so it's that character that you'll pick up when you nose the gin but it's also a really persistent flavour after you've swallowed it.

Chris - Yes, I can still taste that lemony essence now.

Will - So the opposite of that, in many ways, is the top note which I've illustrated here by using an atomizer. It's like a perfume bottle a bit of perfume you can spray directly into your mouth.

Chris - So this is a big square bottle; it's got a squirty thing on the top like perfume. I'm going to spray this just on my tongue, yes?

Will - Straight into your mouth.

Chris - Oh, OK. That's a rosy flavour. It's like rose but it wasn't like the lemon one which I could still taste minutes ago. That was there in a flash. It was like someone detonated a sudden explosion in my mouth that was over in a flash, it's gone.

Will - And that's exactly what we use a top note for. By using the atomiser we're massively increasing the surface area there. It gives you a really intense strong hit but then it disappears. It's almost ethereal, a really sort of elusive element of the flavour that we balance. So what we do is we take all these elements together, wrap those up into one single flavour as it were and then that's how we make gin. But, of course, because not all people are the same, we also offer a gin tailoring service where we can do this and fit a particular gin to each individual person's particular palette.

Chris - Now you've educated me about how you do all this, does this mean Will that you could make gins from ingredients that would, I suppose, be regarded as unusual?

Will - It means exactly that. Certainly the weirdest one I think could be anti-gin.

Chris - Anti-gin, like antifreeze?

Will - Anty gin like ants as in creepy crawlies made from actual ants, yes.

Chris - How do you do that?

Will - Long story short, this was a collaborative project between us and the Nordic Food Lab. They made the observation that some ants from some places have very specific flavours. We actually used a red wood ant which is cytrusy. If it were just a citrus flavour we would use lemons, they don't run away, they don't try and bite you, but they have a completely unique flavour. And all gins have a citrus flavour in them somewhere as well so.

Chris - How do you get the flavour out of an ant? Do you go and dig up and ants nest and just get millions of ants and just do what you would do if they were juniper berries?

Will - Well actually what we do is we work with a chap called Miles Irving, who is a forager in South Kent, and he very cleverly waits for these ants to be on the move. So they go very deep underground to avoid the frost during winter and then in the spring they start to swarm. Now it's very important to us that we use happy ants because if you get upset ants then they express their discomfort by spraying formic acid. Now that's the bit that we actually want so we use these happy ants. Miles will put down a sheet that they crawl over on their swarming journey and pick that up and sort of gently shake them into a high strength ethanol, which conserves the formic acid and despatches them in as humane a way as possible. That ethanol comes back up to us in Cambridge where we distill it.

Chris - Can I have a go?

Will - Of course. So what I'd like to show you first of all is the ant distiller. So this is what the ants taste like when distilled, so this is pure ant distillate.

Chris - Here we go...Mmm it's not at all unpleasant and it's quite a subtle flavour. It tastes gin-y without any actual gin there.

Will - This is how we knew immediately on first tasting that this was a project that was going to be successful.

Chris - Right, so what, you blend that in with your other notes now to get that very nice rustic flavoured gin?

Will - That's right and this is the result.

Chris - It looks like a clear colourless liquid. OK here we go, let me try... Well it's extremely pleasant and it's much more complex and much more interesting than the rather boring base that we tried earlier. Which is a good thing because if it wasn't, obviously there'd be a problem. But no, that's delicious

34:36 - Dinner party tips: part 1

Dinner party tips: part 1

with Professor Charles Spence, University of Oxford

It's not just the food and drink cooking that makes your dinner party a blast - your  mind decides if something is tasty or not for a whole host of different reasons, not all of them related to flavour. Professor Charles Spence is head of the crossmodal research lab in Oxford, and he gave Georgia Mills some tips into how psychology can improve your dining experience.

mind decides if something is tasty or not for a whole host of different reasons, not all of them related to flavour. Professor Charles Spence is head of the crossmodal research lab in Oxford, and he gave Georgia Mills some tips into how psychology can improve your dining experience.

Charles - Intuitively, I guess, we all sort of think, well I like the taste of this or the taste of that and by using that language we can imagine that what we're reflecting, and what we're enjoying is derived solely from what's going on in our mouth, namely from the taste buds on the tongue. And yet what psychology and neuroscience shows is that what's going on in the taste buds and in the mouth is only a very small part of what we all can experience as the taste and flavour of food and drinks. So taste buds themselves give us just sweet, sour, salty, bitter, perhaps umami and a few other basic tastes but all the other interesting stuff in foods, the citrus, the meaty, the floral, the herbal, the burnt, all those notes are coming from our nose instead. Through to the sound of the crunch of the potato chip or any other dry or wet food product that makes a crunch, a crackle, a carbonated, creamy, crispy, squeaky, all of these attributes that we love in food again. We think we're sort of feeling them in our mouth or between our teeth and yet, it turns out that what we hear, the sounds of the crunch or the fizz or the bubbles in your drink, places a much more important role again than we realise. But the neuroscience and the psychology's helping to unpick just how important each sense is.

Georgia - Say I'm having a dinner party, do you have any top tips on ways I could use psychology to make sure everyone has a nice time?

Charles - Yes, indeed. I would say one of the simplest things to do is to increase the weight of the cutlery that your guests hold because that does, in a number of studies now, lead to food being rated better than it otherwise might be with light cutlery instead. I'd think about playing classical music in the background because, generally speaking, that tends to be associated with higher quality, classy offerings. And you find that people in the wine shop will generally ascribe a higher value to food and drink if there's classical music rather than the top 40 playing in the background.

37:02 - Fry me up a perfect fish

Fry me up a perfect fish

with Alex Rushmer, Hole in the Wall, Dr Sue Bailey, London Metropolitan University

How does temperature affect flavour, why does brown food taste better and  how can a blowtorch improve your cooking? Food scientist Dr Sue Bailey and head chef Alex Rushmer have teamed up to take Chris Smith through how to fry the perfect fish.

how can a blowtorch improve your cooking? Food scientist Dr Sue Bailey and head chef Alex Rushmer have teamed up to take Chris Smith through how to fry the perfect fish.

Alex - OK. So I've got some lovely fillets of white fish here. We use cod but you could do the same thing with hake, or turbot, or halibut if your budget allows, but the process is exactly the same. The cod comes in to us, we choose the best possible fish. That's crucial to it. Before we do anything with it we salt it, that's the first thing we do. We liberally season it with just regular table salt, we then leave it in the fridge uncovered for about three quarters of an hour to hour depending on the size of the fish. After that we rinse it, we give it 2-3 minutes in fresh cold water. Then it goes back into the fridge on blue cloth. We dry it as closely as we can, we really get both sides very, very dry. We leave it uncovered in the fridge for about 4 or 5 hours.

Chris - That may sound counterintuitive to some people why you would want to dry fish because some of the things I've had in restaurants in the past. Not yours, because I've not dined in your restaurant but the fish is dry and you think, Uh I don't like that. Why are you drying it?

Alex - So we're drying it to caramelize the outside, we're not drying the inside of the fish. It's a very delicate cure that we put on the outside. A symptom of overcooking fish is a fish that feels dry in your mouth, that's what we're trying to avoid.

Chris - Right, so you dry the surface, then what do you do? Is that straight in the pan or is there another step?

Alex - Before we put it in a pan we blowtorch it.

Chris - Blowtorch it?

Alex - We use a blowtorch to further dry out the skin and begin the caramelization process.

Chris - Is that that?

Alex - We've got one right here

Chris - The same thing you'd see in your garage actually, OK. Well don't burn my microphone or my worktop.

Alex - I'll try not to.

Chris - Here we go... Alex is literally blowtorching the surface of the fish. So we've got the fish sitting in an oven tray and each piece is 10-15 seconds on each piece I'd say?

Alex - Yes, about that. Just enough when you see the colour starting to appear.

Chris - It's just turning, isn't' it? Little tiny black spots here and there on it like dark spots and it's just sort of crisping up. And you're done?

Alex - That's it.

Chris - Now what?

Alex - It's as easy as that. We've got a pan on the heat here. A very, very high heat usually for fish cookery. We've got a little film of oil in there and the fish goes straight into the pan...

Chris - And you're actually holding the fish down, you're actually pressing that down into the oil?

Alex - I'm holding it down very, very gently. What you don't want to do with meat or fish cookery is apply a lot of pressure to it. It's something I see a lot, especially with new chefs in the kitchen or people that cook in their own homes, is they play with the food when it's in the pan or they mess around with it. It's something that you actually want to do is leave it alone, let it cook, let it do it's thing.

Chris - Right I'm going to leave you alone and let you do your thing, do what you do best. I'm going to come over here and have a chat to Sue. Because Sue, can you tell us what Alex is up to, what is actually going on chemically in this frying pan?

Sue - Well, what's going on chemically is that the protein of the fish is beginning to denature. And what's happened is that you really don't want your fish to cook at too high a temperature, typically about 40 degrees centigrade. He cooked it with a blowtorch, that goes up to over 1,000 degrees centigrade but it's just enough to brown it and give the Maillard browning, the browning reaction which you saw. And now what he's doing is just cooking the fish very gently. Normally what happens, you have to cook up to about 110 degrees centigrade in order to get a Maillard reaction. If you did that to the fish, you'd get not very juicy, not such nice fish as he's going to produce.

Chris - You've mentioned a number of words there. Denature was one of them, denaturing the proteins. First explain what that is, and then tell us what this Maillard reaction that you've mentioned a couple of times is?

Sue - Well denaturing is what happens when you have the protein which is typically in layers, what happens is that the protein, as you heat it, denature it, the protein parts of the food begin to unfold. It's what's known as its tertiary layers, and it begins to unfold, and then it begins to firm up...

Chris - The protein changes shape?

Sue - The protein changes shape.

Chris - That's why we get sort of colour change and the texture change?

Sue - That's why you get colour change and so on.

Chris - What about the Maillard, the browning?

Sue - Right. The Maillard reaction is where you have got a reaction between the sugars and amino acids from the protein, and that's what give you a lovely caramely, smokey, flavour, and also the visual effect that you...

Chris - Ah, so that's the good taste?

Sue - That's the good taste, yes.

Chris - So that's why Alex did the blowtorch was to get lots of that Maillard reaction which needs the high temperature but now he's cooking at the slightly lower temperature to avoid destroying the quality of the meat inside? So we've got the best of both worlds, the good taste plus the good texture.

Sue - Absolutely so. That's exactly right.

Chris - How are you getting on Alex?

Alex - Yeah, I think we're looking good. There's some nice colour that's starting to appear on the side of the fish that's in contact with the pan. I think another 30 seconds or so on that side and then we'll flip it over and cook it from the other side, and we'll introduce some butter to the pan as well.

Chris - He's going to put butter in - is that a good idea Sue?

Sue - Oh yes for flavour, yes absolutely. What it's going to do is give you a bit more caramelization on the fish and when you serve it it's going to be nice and foamy, slightly golden brown, nutty flavour and, because you were cooking it before in a very neutrally flavoured oil to have the temperature right, he's now just making sure that it's finished nicely and tastes perfect.

Chris - That's quite a big knob of butter.

Alex - This is the other thing that you don't see in home kitchens and awful lot is the amount of butter that we use in a restaurant kitchen.

Chris - And I'm liking this. You've got that lovely technique of flicking the melted butter over the top of the fish as it goes.. Is that so you don't have to fiddle with it and turn it over like you were saying?

Alex - That's exactly it. So I've got the pan leaning towards me ever so slightly, probably at an angle of about 30/40 degrees. The fish is at the far side of the pan and then there's a nice pool of butter sitting just in front of me here which I can then spoon straight over the fish. You can smell it and you can smell the slightly biscuity nature of the butter.

Chris - it does smell biscuity and it's also browning off the top of the fish as well.

Alex - It's browning of the top of the fish and the butter is foaming as well. That's how we know that the temperature is right. What we don't want to do is take the butter to far and actually burn it, you end up with a slightly bitter flavour.

Chris - Right. As they say on Masterchef you've got 30 seconds to plate that up Alex. We'll just ask Sue - why was the butter all foamy like that?

Sue - That's partially because of the salts and a little bit of the water.

Chris - It's sort of boiling away and driving steam inside the butter?

Sue - It's slightly boiling away driving some steam away making sure that it's perfectly cooked.

Chris - Now talking about perfectly cooked, what can you say about the sort of food safety aspects. How do we know that that piece of fish if it's only 40 degrees in the middle, how do we know that's safe to eat?

Sue - Well, I think this is where Alex is going to use a tried and trusted thermometer which perhaps...

Chris - With his thumb?

Sue - No, no, no! I can just him wiping it off now. Because the important thing is from a food safety point of view, you need to have it at 40 degrees centigrade...

Chris - Or above?

Sue - Or above to make sure that it's safe to eat. And so I've just seen him prodding it now - I don't know what's happening...

Chris - What's the verdict?

Sue - The verdict is it is cooked.

Chris - Georgia - it looks good. Are you going to come and try this?

Georgia - I absolutely want to have some. I'm just going to wiggle over...

Chris - I can't wait. Can I help myself to one of these forks Alex?

Alex - Of course.

Chris - I'm always so jealous of the fancy guys on tele when the do this. So I'm going to have a little bit - here we go... Oh, that's melt in your mouth.

Georgia - Oh here we go.

Chris - I guess that's what you get paid for Alex. Is that what you're going for a sort of it falls apart in your mouth? It doesn't need much effort to make that fish fall to pieces on your tongue.

Alex - That's it. With cod you've got a fish with fairly large flakes which you do want to fall apart. You don't want them to be stuck together. I think that's part of the process of the denaturation of the proteins.

Sue - Yes absolutely. What's happening there is that the collagen in fish melts at a slightly lower temperature than it does typically in meat, so it typically goes at 41 degrees centigrade and the fish is cooked at 40 degrees centigrade. So, as you say, it should just flake apart beautifully but not be overcooked or dry.

45:24 - Dinner party tips: part 2

Dinner party tips: part 2

with Professor Charles Spence, University of Oxford

Head of the crossmodal research lab in Oxford University, Professor Charles Spence is back with more tips on improving your dining experience, and on why size is important when it come to how full you feel...

is back with more tips on improving your dining experience, and on why size is important when it come to how full you feel...

Charles - If you're aiming to try and satisfy with a little bit less, then think about serving off a smaller plate because it will trick your brain into looking like there's more food there, rather than one of those big American style plates where the food looks tiny as a result.

I've recently been very interested in this growing trend towards bowl food. You kind of think what's going on there but it's tied with the healthy eating and it's partly about if food is in a bowl, then you're more likely to pick it off the table, hold it in you hands and feel the weight of the bowl, maybe feel it's texture, that can then enhance the experience. You're more likely to sniff the aromas coming off the food if you're holding that bowl to your face and, again, those food aromas are a key part of the experience and can help you to feel fuller on less. Also a bowl without a rim say, then the food's going to fill almost to the very edge of the bowl and hence, that again, will trick your brain into looking like there's more food. And the final advantage of the bowl, at least for hot food is comes from the social psychology research showing that if you hold something warm in your hand like a warm bowl of food or a cup of tea or coffee, then the world generally looks like a better place and everything around you looks warmer too. This kind of transfer of attributes from what you hold in your hand to elsewhere.

46:58 - Chocolate emulsions for dessert

Chocolate emulsions for dessert

with Adam Geileskey, Hotel Chocolat

The best course of any meal? Dessert! To find out a bit about the physics of  chocolate emulsions, and how to make the perfect ganache, Georgia Mills invited Adam Geileskey, Head of Chocolate Development at Hotel Chocolat for a 'ganache-off'...

chocolate emulsions, and how to make the perfect ganache, Georgia Mills invited Adam Geileskey, Head of Chocolate Development at Hotel Chocolat for a 'ganache-off'...

Adam - Okay Georgia, so we've got a couple of things on the go at the same time. We've got some chocolate melting. I've got some orange juice which is actually Sicilian blood orange warming up and I've got some cream warming up and we're trying to get all of these to the same temperature, about 45 degrees centigrade. So as we know chocolate is sold at room temperature, and then as we warm it up to 45 degrees, it goes a lovely liquid, and what we're going to do is how we can combine these ingredients together to make some interesting desserts and maybe even chocolates.

Georgia - So what's the name of the dessert we're making?

Adam - Okay what we're going to do is have a go at making a ganache. A ganache is when you add chocolate and some kind of liquid. So normally traditionally that's cream but you can do some interesting stuff and we're going to try orange juice today but you could easily do this rum, tea and, in fact, any kind of liquid you can think of we could have a go at making this.

So the science of this is we're making an emulsion. An emulsion is a mixture of two immiscible liquids, so in this case we've got cocoa butter, which is a fat and at 45 degrees it's going to become a liquid, and we're also adding there's water in the orange juice and in the cream. And we're going to be combining both to those, trying to mix it really thoroughly to break the cocoa butter down into tiny little pieces and surround that with a sea of water. Adding the cream and the fruit juice will also give it some extra flavour.

Georgia - So when you say immiscible, you mean they can't mix together?

Adam - Normally no. They can't mix together so if you drop one on top of the other they would separate.

Georgia - Like oil and water, something like that?

Adam - Exactly, like oil and water. And what we're doing with the ganache is very similar to what you do if ever you've had a go at making a mayonnaise, or even paint! The way it works is the cocoa butter will get broken down into such small pieces that it's then held by this sea of water.

Georgia - Great, so we've got some bowls here.

Adam - Right, so we've got two bowls. We've got the cream and the... You're going to have a go at the cream and I'm going to have a go at the fruit juice, OK - we're going to have a ganache off! So I'm just going to now pour some of the melted chocolate into the cream and now I'm going to put some of the melted chocolate into my fruit juice.

Georgia - Chocolate and juice, it just doesn't seem right.

Adam - It's definitely going to work. I'm going to hand you a spoon. You need to get stirring. Get the spoon right in the bottom and get that moving.

Georgia - Oh gosh! I'm spilling ganache everywhere!

Adam - It's going everywhere, it's going everywhere! So you can see what's happening now. To start with it goes really lumpy and what's happening there is the water loving... you're doing really well now... the water loving cocoa powder in the chocolate sucking all the water and then the more you mix it the smoother it gets. And what you're looking for is something that's really nice and shiny and glossy, which actually, yours is looking better than mine.

Georgia - But on the other hand I have splashed it all over you and I'm very sorry about that.

Adam - I'll be having that later. OK so, actually, we can stop now. You've got a beautifully soft and glossy ganache. Actually, that looks really professional - if you're looking for another job we'd be happy to talk to you! Would you like to try some of it?

Georgia - I would love to. I was just waiting for you to say.

Adam - I recommend with your one, I recommend try it with a strawberry.

Georgia - Dip the strawberry... it's nice and warm.

Adam - While you're eating that now, you could use this as it is. This is still really nice and warm - it's like 45 degrees and his is perfect for dipping fruit and stuff like that into and just eating as it is or even a cracker or something like that, which I've also got. But if you left this and you left it overnight to set up properly, the cocoa butter then starts to crystallise. So it starts to go solid again and that firms the whole mix up and that's what we'd use for the centre of a filled chocolate, so a nice soft chocolate. If you then took a scoop of that and rolled it in cocoa powder or dipped it in chocolate, you'd have a nice filled chocolate.

Georgia - OK. So as they are now, they're kind of just a bit liquid and soft and oh.... You've got some here you made earlier Blue Peter style.

Adam - Yes, Blue Peter style - so the one I'd like you to try this is the orange ganache. This is the one that I made that didn't come out as well as yours but it does taste very good.

Georgia - This is on a nice cracker.

Adam - So tell me what you think.

Georgia - ...Oh.

Chris - Can we all try some?

Georgia - Mmm... that's fantastic.

Chris - Alex and Sue look like they're going to kill someone here if they don't get a chance to try it.

Adam - Here's some crackers and some chocolate.

Georgia - Well, I stand corrected. The orange juice and chocolate work lovely together. Does this mean it's a bit more healthy... Sorry you're wiping off all the chocolate I sprayed on you earlier. Does this mean it's a bit more healthier than the cream one, the traditional ganache?

Adam - Yes. If you think about chocolate. Half of the chocolate is cocoa butter and the other half it's a mixture of milk powder and sugar. So, obviously, adding water into that dilutes the energy parts of the ingredients so, if you were using a fruit juice, that then reduces the amount of fat in the chocolate. But then, if you were making this say with a tea, so maybe something really interesting like a matcha tea or an earl grey tea, you're just adding really water and flavour and that would do an even better job in terms of reducing the calorie count in that filled chocolate.

Georgia - I can't wait to experiment with all the different liquids. And so, just to summarise, it's basically as simple as melting the chocolate to 40 degrees, mixing it in with the liquid of choice and then leaving it to set in the fridge or just eating it all immediately with strawberries, as I tend to do with these ones.

Adam - Yes, pretty much. So the important thing is melt you chocolate, I'd melt it to just over 45 degrees, make sure you combine all your ingredients at the same temperature. Imagine if you add cold cream to warm chocolate it just sets the chocolate and makes your grenache go really lumpy, and then get on and mix those as fast as you can, and then just sit back and enjoy it. The advantage of this as a dip at the dinner table is that it takes a lot longer for it to set so you can enjoy it for longer.

Georgia - And this is the friend of the chocolatier. You can use this to make fillings for chocolates like those mojito chocolates we were eating naughtily before the show?

Adam - Ah we use all sort of things in this type of recipe, so we add all sorts of alcohol. So I would have a go with gin, I think that would work really really well. We use all sorts of vodkas and then equally we have a recipe with carrots, like carrot cake type recipes. We've got some really interesting cocktails like mojitos and then in some of our recipes we'd use real champagne and make things like champagne truffles, so it's really versatile.

Chris - Can I ask you a question though? How do you get the alcohol to stay inside the chocolate without sort of eating it's way out?

Adam - If you're making a ganache you don't really have a problem with that. What you do is you make your ganache up to this stage and then you add your alcohol. Don't try and hear everything up with your alcohol. Make your ganache first and then add your alcohol into it so it goes in last - it lasts really well. But do keep your ganache... If you are going to have a go a making them keep your grenache in the fridge because this is a really simple recipe and it needs to be kept refrigerated otherwise it will eventually go off, and it lasts for a few day.

Chris - What do you think Will?

Will - It looks, and sounds, and tastes delicious. I'm a fan!

Chris - You're tucking in Sue.

Sue - Oh yes. I've just tried a little bit and it's perfect!

Chris - You'll be going back for more. Alex - is that something you could serve up in the restaurant?

Alex - Yeah, I think it's a great idea. We make all our own petit fours and chocolate truffles to go out with coffees at the end of a meal and I think this is a great addition to it.

54:02 - How do octopuses camouflage themselves?

How do octopuses camouflage themselves?

Graihagh Jackson put this question Felicity Bedford, from the University of Cambridge...

Felicity - So your listener's absolutely correct. they are colour blind so they only see in black and white and the shades of grey in the middle. And all of the colours appear within that spectrum to an octopus so a much simpler world in terms of colour.

Graihagh - So how on earth do they then go about camouflaging with the environment if they're colour blind?

Felicity - Other than the fact that they can't see colour, they have incredibly good vision. So they can get a lot of accuracy about their environment, about the texture of their environment, about the brightness of their environment, and these are all really important things for when you're camouflaging to break up your outline, break up the pattern of your body. And generally, the way that predators pick out their prey is through movement, through brightness and through colour. So by getting the movement and the brightness right, they're taking away a few of the things that predators can use to spot them, and then it's only colour left. And we think this is probably due to the way that there's a limited set of colours available and octopuses use something called chromatophores in their skin. So they've got a range of pigments to work with and these are pushed towards the surface of the skin to change the colour, so lots of different sacks of colour that are pushed and manipulated and quite frankly, if they get it wrong they get eaten. So there's a sort of evolutionary pressure there.

Graihagh - And presumably I'm thinking octopuses are underwater and, if you've ever been diving actually, it's not that colourful down there in the first place so it's not actually that useful to see in colour anyway.

Felicity - No you lose a lot of different light frequencies under water, particularly the reds that get filtered out very early on. And the chromatophores that they're using are in the blacks, the browns, the oranges, yellows, those kinds of colours, so they do tend to go into those ranges. And there are some other cells that they can use which bring luminescence of blues and greens, which actually reflect light rather than using these pigments instead. So they've got a lot of things that they can use to change their colour but they're not necessarily aware of the colour they are.

Comments

Add a comment