Remembering makes you forget

Interview with

The process of recalling memories also involves actively forgetting things. Researchers at Birmingham University asked a group of volunteers to memorise pairs of things, but then to recall just one of the pair,  forcing their brains to suppress the memory of the other item, which ultimately led to it being forgotten, as Maria Wimber explains to Chris Smith...

forcing their brains to suppress the memory of the other item, which ultimately led to it being forgotten, as Maria Wimber explains to Chris Smith...

Maria - Imagine you're standing in front of a cash machine and you just got a new bank account. So, you're desperately trying to remember your new pin code but the old one that you've used for a couple of years keeps popping up back in your mind. You can probably imagine that in those situations, it's quite useful to have a mechanism that helps us forget the old pin code in order to better remember the new one.

Chris - So, what is the mechanism that's at play to solve that so that I can remember my pin code despite having lost my card and had it replaced - God knows how many times.

Maria - What we show in the study is that the brain has a mechanism of actively getting rid of information that constantly blocks our access to the information that we're really trying to recall. Like in the example of the bank account or the bank pin, it's trying to get rid of the old pin in order to make it easy in the future to retrieve the new pin.

Chris - Are you saying then that by remembering one thing, I am actively forgetting another?

Maria - Absolutely, yeah. I think it's important to mention that it's an active process that is happening. So, it's not just that we passively forget the information that we don't use, but remembering actively shapes which information we retain in long term memory and which one gets lost.

Chris - Is that an irreversible loss?

Maria - In the long term, it might be, yeah.

Chris - Gosh! That sounds a bit worrying. How did you find this?

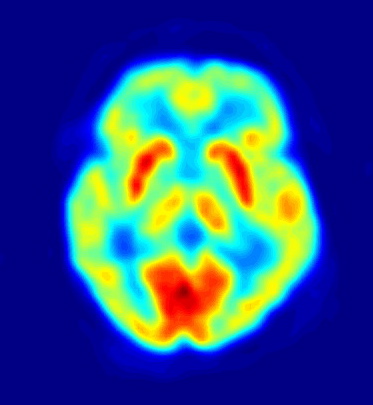

Maria - New developments in brain imaging have made it possible recently to decode just based on somebody's brain activity what picture for example somebody is looking on right now.

Chris - And this is because you have shown those people those pictures before and looked at what their brain did when they were looking at those pictures. So, you can, in that person, say, with that pattern of brain activity correspond to them viewing a picture of Einstein or Marilyn Monroe.

Maria - Absolutely. We show people the same pictures over and over again. So, we can sample something like the prototypical fingerprint that Albert Einstein leaves in the brain. The challenge for us was then to ask, well, using these neurofingerprints, can we even try to decode what somebody is thinking of, or what somebody is recalling from memory at a given time? And the answer is yes. We were able to do that and the studies that we were able to track individual memories as they come back in the brain when people are remembering something. So, we trained people to create certain links in their memory, links between words and different kinds of pictures. So, we knew that each of the keywords that we were using would elicit two different pictures in their brains. So, the word 'sand' for example might have been linked to Barack Obama, but also, to a picture of a rope. So, when we ask people to remember only the face that had been linked to this word, we could actually watch whether their brain was able to bring up the face of Barack Obama and at the same time, to suppress the picture of the rope that is interfering or distracting them at this time.

Chris - I see. So, in other words, when you're saying to them, "We only want the face" but because the word you're cuing them to remember the face with is also linked to another memory, the brain needs to be able to suppress the rope so that it doesn't interfere with them thinking about Barack Obama and you can actually see that happening.

Maria - Exactly.

Chris - How do you know that the brain is suppressing the image of the rope?

Maria - So, it's not just the neuro-fingerprint of the rope is more and more fading out. But the picture of the rope was being suppressed for example below the picture of a hat that wouldn't interfere during the task.

Chris - The brain is actively deactivating that fingerprint that would correspond to the picture of the rope in the minds of these people. So, you see a very strong representation of Barack Obama, but the representation that would normally correspond to the rope is being more and more eroded.

Maria - Absolutely, yes.

Chris - Goodness and so, that suggests that the brain has actually actively unwritten the memory of that association.

Maria - It sounds a bit scary but yes, that's probably the essence of it.

Chris - What would be the implication of this then in everyday life, apart from actively, when you learn something new and you overwrite a memory, what other implications might there be?

Maria - Most people tend to think of forgetting something that is like a failure of a memory system. But I think in most situations, forgetting is actually something incredibly useful. To give you a real life example, this forgetting might become really relevant when you're studying for exams. It's often recommended that you test your own memory often enough. So, you read a chapter in the book and then you use for example flashcards to test your own memory. This is actually a very good idea. Testing your own memory makes your memory better and more stable in the long term. But it can also make you prone to this negative side effect of remembering which is forgetting related information. So in simple words, when you study for an exam and you use flashcards to test yourself, try to do this comprehensively. So, test yourself on everything you have just learned and don't leave out any information because by testing yourself on some pieces of information, you might actually lose other pieces of information.

Comments

Add a comment