When our ancestors migrated out of Africa 100,000 years ago, a highly perfected killing machine was unleashed on the rest of the world, catching the local fauna off-guard...

Wherever humans have travelled, we have left a trail of destruction behind us: species have gone extinct on every continent that we have invaded, from the woolly rhino in Europe to the giant wombat (Diprotodon) in Australia. But, even though pre-historic extinctions have a strange tendency to coincide with human arrival, there is a lack of solid evidence demonstrating exactly when, and how, humans caused animals to die out, because eons of time have passed since it happened. In this regard, New Zealand is unique, as it was the last major landmass to be settled by humans. It was only 750 years ago that Polynesian seafarers reached its pristine coasts, where a unique and ancient fauna, dominated by birds and reptiles, roamed. Not surprisingly, human hunting rapidly drove many species to extinction, of which the best known example is the (undoubtedly tasty) giant chicken, the moa. On top of that, since the arrival of European settlers on the archipelago in the 18th century, extinction rates have accelerated, and the loss of habitat as land is cleared for farming has pushed several species to extinction during the past 100 years.

Reconstructing the diet of the past

So, how do archaeologists know what animals were hunted in New Zealand 750 years ago? Most of the information we have today comes from picking through the ancient trash of prehistoric settlements. Incredibly, the leftovers from meals cooked hundreds of years ago are still preserved in ancient waste dumps called middens, which, when excavated and dated, tells us a story of past diets. But we rely on bones that are intact and easy to distinguish from those of other animals. Unfortunately, such intact bones are rare, and typically the majority of excavated bones are in such small pieces that they cannot be told apart. So we do not know what animals a large proportion of bones found in middens came from, which in turn suggests that we might be missing important species in our dietary analyses of past cultures (imagine a jigsaw puzzle with half the pieces missing). In New Zealand, for example, it still remains a mystery exactly how, and when, the numerous species that disappeared were wiped out. Did they go extinct quickly, or did they survive until historic times only to be eradicated by Europeans? And for the species that made it and are still alive today, to what extent has human arrival affected their populations?

DNA from bulk bone

Intrigued by the vast amounts of bone pieces that are impossible to identify in excavations, we set out to analyse the DNA in them. Fortunately, most Museums save every piece of bone unearthed from excavations, even the seemingly worthless ones. Working with the University of Otago, Canterbury Museum and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, we collected over 5000 small bone pieces from 21 ancient middens and from 14 caves. By comparing bones excavated from caves that pre-date human arrival with bones from middens, we can estimate the loss of biodiversity in New Zealand over time.

We found genetic signatures from a vast array of different species of birds, marine mammals, fish, frogs and reptiles. In total, we identified over 100 different species of which 14 are extinct today. What was particularly surprising was that we were able to detect species that are typically missed by morphological approaches. For example, we detected DNA from five different species of whale: orca, dolphins, Cuvier’s beaked whale, fin whale, and southern right whale. Except for the southern right whale, none of these species had been previously identified in an archaeological context in New Zealand.

By combining these results with previous studies of bones excavated from middens in New Zealand, we now know that a range of different species were hunted in prehistoric New Zealand. Upon arrival in New Zealand, Polynesian settlers went after the biggest and tastiest target: the moa. When the moa went extinct, they turned to seals, which soon also disappeared from the mainland. With the disappearance of these important sources of food, the settlers next exploited smaller species and they turned to fishing. In the DNA data are an abundance of different fish species, which reflects the fishing waters surrounding each ancient settlement. Each midden was dominated by fish species common to that latitude today, suggesting that the Māori were loyal to their local fishing grounds and that they didn’t trade or travel long distances to go fishing.

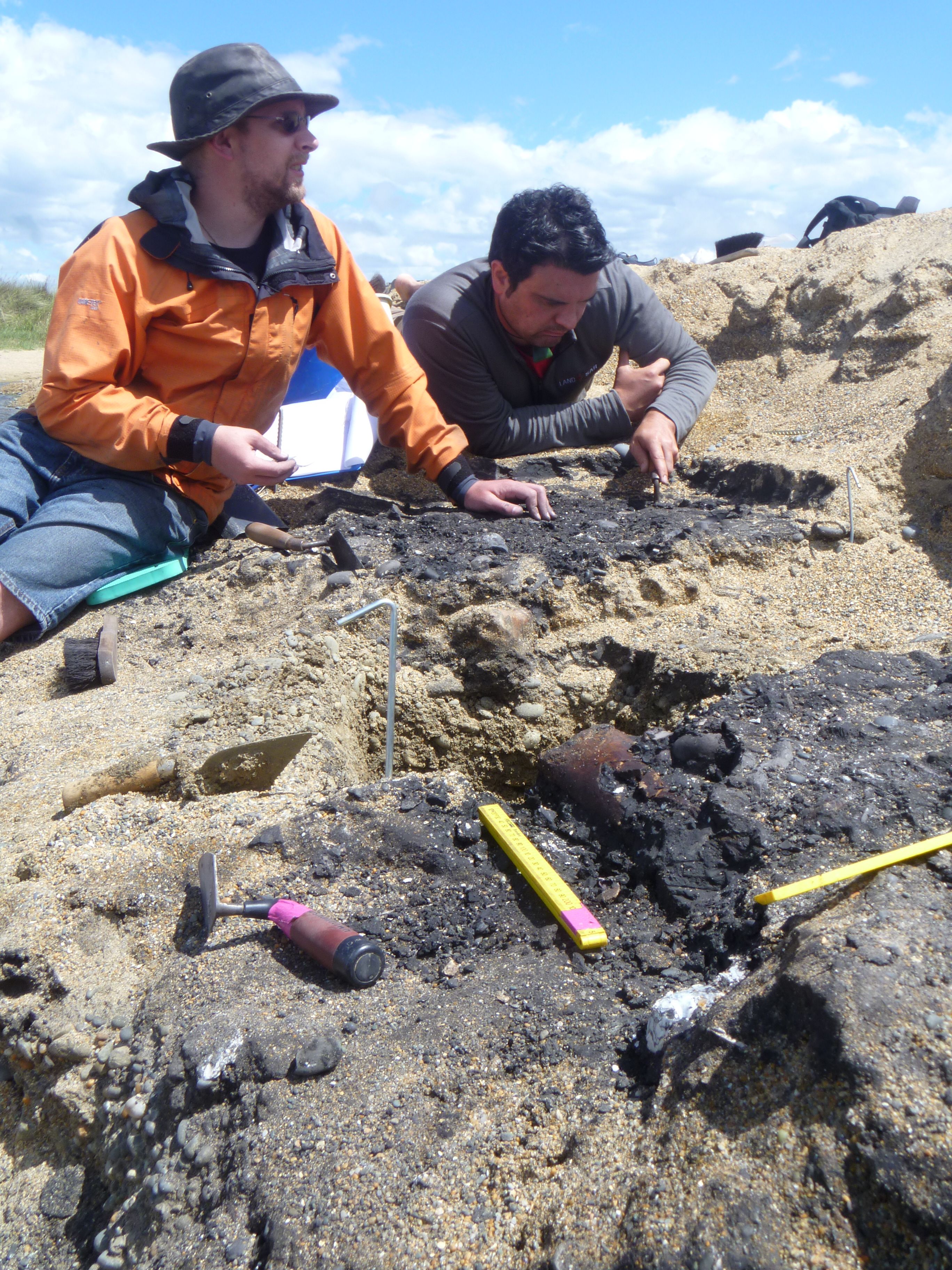

Nic Rawlence and Kyle Davis (Ngai Tahu iwi member) excavating a midden at Awamoa, New Zealand (Photo by Shar Briden)

Shrinking animal populations

Since humans got to New Zealand half of the terrestrial birds have gone extinct, and for the birds that survived it was not a walk in the park either. The nocturnal parrot the kākāpo was once thriving on both islands of New Zealand; today it is extremely vulnerable and the current population size is estimated to be around 150. We found that a total of ten different kākāpo lineages populated New Zealand before human arrival. Of these, only one lineage remains today. This demonstrates how genetic diversity in the kākāpo population has been constantly declining since human arrival in New Zealand. Similarly, for the endemic leiopelmatid frogs of New Zealand, we found that the past diversity was much higher in the past than it is today. We found DNA evidence suggesting that the endemic Markham’s frog was once widespread on the South Island of New Zealand. Today it is extinct.

The biodiversity in New Zealand has been declining continuously over the last 750 years, and there is no doubt that this decline is caused by human activities. While this phenomenon is extremely well documented in New Zealand, because of the short time that has passed since it happened, it is not unreasonable to assume that something very similar happened across the rest of the globe. Back then, we did it to survive, unaware of the impact we had on the fauna around us. Today, extinction rates are higher than ever before, and we are aware of what is happening. So perhaps it is time break the trend that started when we left Africa, before it's too late for the rest of nature...

Comments

Beautiful pic of the site at

Beautiful pic of the site at Awamoa, New Zealand. Caral is another site of what may be the oldest city in the Western Hemisphere. Constructed some 4,700 years ago in what is now the Norte Chico region of Peru, just north of Lima in the Supe Valley, Caral ranks on the short list of regions, along with Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, as the first to develop what most people would call civilization. Covering 165 acres, the site is one of the largest in Peru, a country with the most archaeological sites in South America. The site contains six pyramids, some originally as high as 70 feet, circular plazas and massive monumental architecture. Caral’s architectural style seems the precursor for subsequent Andean civilizations for the next 4,000 years.

Add a comment