In England and Wales some one has a stroke every 5 minutes, that's 100,000 people each year. Anyone can have a stroke, including babies and children, but around 90% of strokes occur in people over 55. The Stroke Association estimates that some 300,000 people are currently living with disabilities caused by a stroke and that up to one third of people who have a stroke will die within the first year, another third will make a good recovery, while the final third will be left with moderate to severe disabilities. A stroke is an interruption of the blood supply to a localized area of the brain* The brain is the nerve centre of the body, controlling everything we do or think, as well as controlling automatic functions like breathing. In order to work, the brain needs a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients. These are carried to the brain by blood through the arteries. If part of the brain is deprived of blood, brain cells are damaged or die. This causes a number of different effects, depending on the part of the brain affected and the amount of damage to brain tissue.

What are the symptoms of a stroke ? Stroke is well named because, for most people, symptoms come on literally at a stroke. The key symptoms include: sudden numbness, weakness or paralysis on one side of the body. Signs of this may be a drooping arm, leg or eyelid, or a dribbling mouth, sudden slurred speech, difficulty finding words or understanding speech, sudden blurring, disturbance or loss of vision, especially in one eye, dizziness, confusion, unsteadiness and/or a severe headache.

What causes a stroke ? There are two main types of stroke, and each has different causes. The first type, an ischaemic stroke, occurs when a blood clot blocks an artery serving the brain, disrupting blood supply. Very often an ischaemic stroke is the end result of a build up of cholesterol and other debris in the arteries (atherosclerosis) over many years. The second main type of stroke is a haemorrhagic stroke, when a blood vessel in or around the brain bursts, causing a bleed or haemorrhage. Long-standing, untreated high blood pressure places a strain on the artery walls, increasing their risk of bursting and bleeding.

A subarachnoid haemorrhage, in which a blood vessel on the surface of the brain bleeds into the area between the brain and the skull, known as the subarachnoid space.

Who is at risk from stroke ? A number of different factors increase the risk of stroke, including:

- Untreated hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Atrial fibrillation. (An irregular heartbeat that increases the risk of blood clots forming in the heart, which may then dislodge and travel to the brain.

- A previous Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA) or 'mini stroke'. Around one in five people who have a first full stroke have had one or more previous TIAs.

- Diabetes. People with diabetes are more likely to have high blood pressure and atherosclerosis, and so are at much higher risk of stroke.

- Smoking. This has a number of adverse effects on the arteries and is linked to higher blood pressure.

- Regular heavy drinking. Over time this raises blood pressure, while an alcohol binge can raise blood pressure to dangerously high levels and may trigger a burst blood vessel in the brain.

- Certain types of combined oral contraceptive pill. These can make the blood stickier and more likely to clot. They may also raise blood pressure.

- Diet. A diet high in salt is linked to high blood pressure, while a diet high in fatty, sugary foods is linked to furring and narrowing of the arteries.

- Age. Strokes are more common in people over 55, and the incidence continues to rise with age. This may be because atherosclerosis takes a long time to develop and arteries become less elastic with age, increasing the risk of high blood pressure.

- Gender. Men are at a higher risk of stroke than women, especially under the age of 65.

- Family history. Having a close relative with stroke increases the risk, possibly because factors such as high blood pressure and diabetes tend to run in families.

- Ethnic background. Asians, Africans or African-Caribbeans are at greater risk. The reasons are not yet fully understood but are partly linked to factors like diabetes, which is more common in Asians, and high blood pressure, which is more common in people of African descent.

What are the effects of a stroke ? The effects of a stroke vary enormously, and depend on which part of the brain is damaged and the extent of that damage. For some, the effects are relatively minor and short lived; others are left with more severe, long-term disabilities. Common problems include:

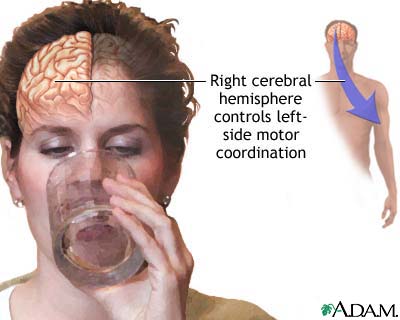

- Weakness or paralysis (hemiplegia) on one side of the body. Because the right side of the brain controls the left side of the body (and vice versa), hemiplegia occurs on the opposite side of the body to where the stroke occurred.

- Speech and language difficulties. Many people experience problems with speaking, understanding, reading and writing. These problems can range from temporary difficulty in finding words, to a complete inability to communicate. Most people who experience speech and language problems have damage in the left side of the brain, which is responsible for language, reading, writing and numbers.

- Difficulties in perception. There may be difficulty recognising familiar objects or knowing how to use them. There may also be problems with abstract concepts such as telling the time. Although vision may not be affected directly it may be difficult for the brain to interpret what the eyes see.

- Cognitive problems. A stroke often causes problems with mental processes such as thinking, learning, concentrating, remembering, decision making, reasoning and planning.

- Fatigue. Tiredness is very common after stroke, though the causes for this are unclear.

- Mood swings. As with any serious illness, emotional ups and downs may be experienced following a stroke. Depression, anger, low self-esteem and loss of confidence are also common. Sometimes people experience difficulties in controlling their emotions and may cry, swear or laugh at inappropriate times.

How is a stroke diagnosed? A number of investigations can help identify the type of stroke that has occurred and the best treatment options. The precise tests will differ from person to person, but common ones include:

- blood pressure measurement

- blood tests to check blood sugar, clotting and cholesterol levels

- chest X-ray to check for heart or chest problems

- an electrocardiogram (ECG) to measure the rhythm and activity of the heart

- an echocardiogram, a type of heart scan, to check for heart problems

- brain scans to determine the type of stroke and to look for signs of damage

- an ultrasound scan of the carotid arteries to check blood flow to the brain

How is stroke treated? Depending on the severity of the stroke, the person will either be admitted to hospital or receive treatment at home. Wherever treatment takes place, in the early days the aim is to stabilise the condition, control blood pressure and prevent complications. The doctor may prescribe drugs designed to prevent a further stroke and to treat any underlying conditions, such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol levels. There are literally hundreds of drugs available and the ones prescribed will depend on the patient's specific needs. Many people who have had a stroke are prescribed aspirin because it helps make blood less sticky and less likely to clot.

How are stroke victims rehabilitated ? Once the patient is stable the medical team will work out an individual rehabilitation programme designed to help them regain as much independence as possible. The purpose of rehabilitation is to help people relearn skills they have lost, to learn new skills and find ways to manage any permanent disabilities they may have been left with. A rehabilitation programme is likely to include methods designed to help with posture, balance and movement, together with any special help needed with specific difficulties such as speech and language.

Many different professionals may be involved in this, but a patient's motivation and efforts are equally important. Key experts likely to be encountered include doctors and nurses (specialist stroke nurses or community nurses) to oversee medical management; physiotherapists to help with problems of posture and movement; occupational therapists to help with everyday activities at home, leisure and work; speech and language therapists to help with communication problems; and clinical psychologists to help with problems affecting mental processes and emotions. A number of other professionals may also be involved, including social workers, dieticians, chiropodists and ophthalmologists (eye specialists).

How long will it take to recover from a stroke ? The brain is a remarkable organ and is capable of adapting to change. In the weeks and months following a stroke many partially-damaged cells recover and start to work again. Meanwhile, other unaffected parts of the brain take over jobs that were previously performed by the brain cells which were destroyed. The length of time it takes to recover varies widely from person to person. It is common to have an initial spurt of recovery in the first few weeks after the stroke as the brain settles down. As a rule, a majority of recovery often takes place during the first year to 18 months, but many people continue to improve over a much longer period.

MRC Cognition & Brain Sciences Unit Rehabilitation Section The MRC Cognition & Brain Sciences Unit Rehabilitation Section is undertaking some truly fascinating stroke related research in the area of Unilateral Neglect. With colleagues at Addenbrooke's hospital and within the Unit, Tom is investigating the processes that may contribute to recovery and investigating the mechanisms that underpin effective rehabilitation techniques.

|

Figure 1 - The right cerebral hemisphere controls movement of the left side of the body. Depending on the severity, a stroke affecting the right cerebral hemisphere may result in functional loss or motor skill impairment of the left side of the body. In addition, there may be impairment of the normal attention to the left side of the body and its surroundings. |

Over 80% of people who experience damage to the right side of their brain due to stroke will - at least for a short time - show something rather strange; they will behave as if the left half of the world simply isn't there. They might fail to respond to someone approaching them from the left, leave the left half of the food on their plate untouched, not shave one side of their face or completely ignore one side of their body. About 60% of patients with damage to the left side of their brain will experience similar problems noticing things on their right. These problems are termed "unilateral (i.e. one-sided) spatial neglect".

Below is a picture of a man drawn by (let's call him) Morris (a 63 year old accountant who suffered a right hemisphere stroke and thought that he might have "a slight problem with his arm"). He was also asked to draw numbers onto a clock face. Morris was, and remains, a bright man and yet he could see nothing wrong with the pictures. We asked him to cross out all of the lines that he could see on a page - again, he could see nothing amiss with his performance.

|  |

Figure 2a - Stick-man drawn by a patient with a right hemispheric stroke. Note the absence of the left hand side body parts | Figure 2b - Clock face drawn by the same patient. Again, note the failure to complete the left hand side of the image. |

|

Figure 3 - Line crossing task results of a patient with right hemisphere stroke |

What can explain this problem? It could be that people like Morris have a visual problem that makes it hard to see things on the left. That is quite common after a stroke but cannot explain this unilateral neglect.

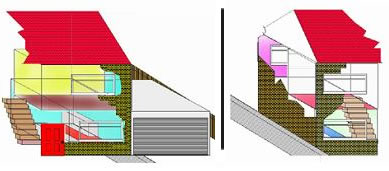

A good example of this can be seen in Morris' description of his house. Morris had lived in the same house for 20 years and knew it "back to front". In hospital, we asked him to describe his house, imagining that we were approaching it from the front. The first thing he told us about was the fence on the right hand side. When we asked if there was anything more that he could remember, he told us about the garage - next to the fence. With continuous prompting we managed to get descriptions of the fence, garage, kitchen, two bedrooms and a hall (see figure 4a below). Morris then stopped - there was nothing more of the house to describe. We then asked him to imagine walking with us around to the back of the house and for him to again tell us about the house. From this new perspective we suddenly learned about a lounge and further bedrooms that were entirely missing from his initial description - when they were on the imagined "left"). This example (based on previous research by Bisiach) shows that even for Morris, access to his memories crucially depends on where he views that information as being in relation to himself - and is certainly something that we certainly can't explain purely by a loss of vision.

|

Figure 4a - Patient with right hemisphere stroke. His description of his house as he imagined approaching it from the front (left) and as if from the back (right). All of the information about his house is represented in his memory (figure 4b, below) but his access to that information depends crucially on where he imagines himself standing. |

|

Figure 4b - How the complete house looks when the patient's descriptions of its appearence from the front (above left) and back (above right) are combined. |

The high frequency of unilateral neglect following stroke, the relationship between right sided brain damage leading to us ignoring left space, and left sided brain damage leading us to ignore right space, when taken together with results from patients like Morris, suggest that although the world appears as a single entity, the hemispheres of the brain give the perceived world an inherent sense of "leftness" and "rightness".

The balance between these is delicate and very vulnerable to disruption from damage to one side of the brain.

Because patients like Morris are often entirely unaware of their difficulty it suggests that, when the balance is disrupted, we don't see the world as half complete - rather, we see one side as the entire world.

The good news is that most patients recover their "balance" within hours or days of their stroke. This process strongly favours those with damage to the left side of their brain and almost all patients with long-lasting unilateral neglect have right-sided damage and ignore left space. For those patients, it is a very serious clinical problem that leads to high degree of dependence on others for many everyday activities. The patterns of rapid recovery - and the imbalance between patients with left and right hemisphere damage may provide some clues that can help with the rehabilitation of unilateral neglect. If we know how most patients compensate for the problem can we help those who are less fortunate to do so?

The first important clue is the observation that most patients with unilateral neglect can notice things on their "bad side" if they are reminded to do so. The problem is that they tend to quickly forget to do this themselves (imagine that someone pointed out to you that, just to the left of the world that you can see, there is a little bit more information.)

A second clue comes from observing patients who have made an apparently good recovery. Researchers have found that if these patients are asked to do an 'attentionally demanding' computer task (a bit like being asked to do mental arithmetic), while their attention was elsewhere, their neglect came back. This suggests that the patients are actively using attentional resources to overcome their problem - to force themselves to notice a world that, without this effort, does not exist.

Research goals This suggests a two pronged approach. Firstly we might want to use techniques that make patients more aware of the left without them having to think about it. Under this category come many weird and wonderful techniques such as putting warm water into one ear and cold water into the other (this appears to fool the brain into thinking we are turning around), looking at a moving background of dots (that does much the same thing), and adapting to prism lenses (ditto). Each have these have been found to improve patients ability to detect information on the left. Some very promising results from Prism lens adaptation have shown benefits that last for at least 6 weeks. Secondly, if we work to increase patients more general "pool" of attentional resources, they may be able to compensate for their problems more easily. Work conducted in Cambridge, for example, showed that training patients to get into an alert, attentive state before they did a spatial task had significant benefits. This approach also suggests an area where drug therapy may be increasingly important. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

*We gratefully acknowledge and thank The Stroke Association for allowing us to paraphrase their booklet 'QUESTIONS and ANSWERS' by Patsy Westcott for the initial Q&A section of this article.

** We gratefully acknowledge Yahoo.com Health Encyclopedia for the diagram of the right cerebral hemisphere controlling left side motor co ordination. http://health.yahoo.com/health/encyclopedia/000726/i18011.html

References

- Previous Space Rockets Save Fish

- Next Heart Disease gets in a FLAP

Comments

Add a comment