Finally, 40 years after the norovirus bug that causes intestinal trouble for millions every year was discovered, scientists have found a way to grow the virus in the laboratory.

Every year, norovirus infections leave millions of people locked to lavatory seats with diarrhoea and vomiting. In the third world 50,000 children die of the disease annually usually through dehydration and debilitation.

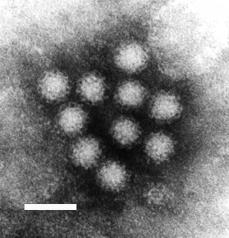

Noroviruses are tiny. The individual virus particles measure only about one thirty-thousandth of a millimetre across, smaller than some particles of smoke, and ingesting just ten of them almost guarantees an infection.

A person symptomatic with norovirus will also be hurling out sufficient amounts of virus in what leaves their body to infect the entire world population many times over.

So it's not really surprising that noro infection is the leading cause of gastrointestinal infections in developed countries. But what is surprising is that, despite 4 decades of effort, scientists have never been able to grow the virus in culture in the laboratory, which has greatly hampered efforts towards understanding the biology of norovirus and the development of vaccines and other therapeutics to treat it.

Now researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, Texas, have pioneered the world's first norovirus culture system.

Using a system developed by scientists in the Netherlands, they have used stem cells collected from human intestines to produce structures called "human intestinal enteroids", which could also be dubbed "mini-guts".

These enteroids recapitulate the natural three dimensional cell architecture of the intestinal lining, which appears to be critical to the ability of the tissue to support the growth of noroviruses.

Enteroids grown using stem cells harvested from different regions of the small intestine were all able to be infected and, within hours, were releasing large numbers of viral particles in the culture medium.

Under an electron microscope, the particles resembled norovirus particles and, most critically, according to Mary Estes, who led the new study which is published this week in the journal Science, the viruses could be used to infect new cell cultures.

"We can passage the virus in culture," she says, although the team don't know why their approach works while others have failed. "I can only speculate that the previous standard lab transformed cell lines tested may lack a receptor or have altered signaling pathways that either don't support or inhibit replication," says Estes.

Crucially, the discovery paves the way to study human noroviruses in a standardised and reproducible manner. This will help scientists to understand how these agents cause disease, what makes some individuals more susceptible to infection, and it brings the prospect of a vaccine against the world's worst food-poisoning offender a step closer.

Comments

Add a comment