Interview with Dr. Fred Piel

The number of people with sickle cell anaemia is set to rise dramatically in the next 40 years.

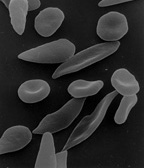

Sickle cell anaemia is a blood disorder that affects around 2 million people worldwide. It causes the haemoglobin inside red blood cells to aggregate, distorting the cells into a sickle shape under low oxygen conditions.

As a result the red blood cells become trapped in small blood vessels, called capillaries, which supply oxygen to the tissues. The disease also lowers the amount of oxygen that can be carried in the blood, because the condition causes the patient's haemoglobin to be less efficient at holding oxygen.

Consequently patients with sickle cell have a reduced life expectancy, although with proper management they can live to their 70's. But that does rely on the standard of health care they have access to.

High income countries have a 10% mortality rate for under fives with sickle cell, whereas in low-income countries the mortality rate can be exceed 90%.

As the population is set to rise, the incident of Sickle Cell Anaemia will rise as well. Now, in a study in PLoS Medicine, Dr. Fred Piel and his colleagues from Oxford have looked at the impact of predicted population rises, based on data from the World Health Organisation (WHO), to give an idea of where the burden of sickle cell anaemia will fall most heavily.The team offer three scenarios.

The first covers what might happen if we do nothing. The mortality rates stay as they are and education and health care receive no additional investment.In this case the number of deaths a year due to sickle cell would rise dramatically, in line with the rise in population.

The second scenario considers what the outcome would be if we could drop the mortality rate to 50% in low income countries and to 5% in high income countries. This could be done through screening pregnant women and making antibiotics available to combat the infections frequently suffered by sickle cell patients. This approach is predicted to save 5,302,900 children by 2050.

Scenario three is even more optimistic. It suggests introducing more specialized clinics, screenings and antibiotics which could achieve a mortality rate amongst under 5s of just 10% in low-income countries and 0% in high-income countries. This could save nearly 10 million lives over the same period.

However, as Dr. Piel has said "whatever scenario is tested, the burden is likely to increase"

Such an intervention would put a large strain on the health care services of their respective countries, as children who would have previously not survived past the age of five, would then require health care.

To limit the healthcare costs to of the countries affected by this rise in sickle cell anaemia, education about inheritance patterns may be the best option, which would help avoid the birth of affected individuals.

It is predicted that even if only the most affected countries were targeted, 10million children could be saved in the next 35 years It seems clear that countries need to start planning how the rise in sickle cell anaemia will be tackled; this study shows the human cost if they don't.

- Previous Nanothermometer takes cell temperature

- Next Palm oil genes

Comments

Add a comment