Obsessive compulsive disorder - OCD - is a mental health condition where intrusive, unwanted thoughts can become all consuming. Some people report anxieties over something terrible happening to them or someone they love for example, and, in some cases, in a bid to alleviate these fears, they may carry out compulsive actions repetitively to the point they become extremely disruptive to their lives.

Due to pervasive misconceptions around this serious psychiatric condition, a lot of people suffer with their symptoms for a long time before getting help. It’s also complicated to unpick the mechanisms of the disorder, as James Tytko explores...

In this episode

Living with OCD

Patrick Dolan

Due to pervasive misconceptions around this serious psychiatric condition, a lot of people suffer with their symptoms for a long time before getting help. It’s also complicated to unpick the mechanisms of the disorder, and we’ll be exploring the ideas at the cutting edge of current research in this programme. But first, to help us understand a bit more about OCD, I’ve been speaking with Patrick Dolan, a third year student at the University of Cambridge. He first started noticing abnormal behaviours when he was 16 years old…

Patrick - Checking doors were locked, checking I hadn't left the hob on, continuously making sure my dog was inside and I hadn't left him outside when I was about to leave the house. It also manifested in ways in my studies, so I had to constantly reread paragraphs because I wasn't sure whether I'd completely understood it. I'd get stuck on certain pieces of work because completing it just didn't feel right. And turning in assessments, they had to be perfect for the teachers.

James - Distortions of useful behaviours. Checking your work, something that would make sense to do, making sure the hob's not on so you don't burn the house down, but how would you describe it to someone who's not familiar how it turns into something more than just a rational thing?

Patrick - Like you say, a lot of the behaviours actually stem from normal things you would do every day. However, the obsession comes when you go back to it multiple times. Even if you see, for example, that the hob is turned off, it doesn't feel right in your head that it is turned off and that's where the compulsions kick in. You might need to turn it off and on, off and on, off and on. You might need to keep revisiting it or in some more severe cases, if it's not treated, you might for example leave the house and get five minutes down the road and then think, did I turn the hob off? And in some cases that might require you to return back, go into the house and check the hob is off. That cycle can go on forever and ever until you actually feel satisfied in yourself.

James - It's, I can imagine, extremely exhausting when people claim to be a little bit OCD, which is a gross misunderstanding of the genuine psychiatric condition experienced by people like you.

Patrick - Exactly. And I think mental health is something that's more talked about nowadays, and we do have the words to speak about it and people are becoming more comfortable speaking about their own feelings. However, for example, if you say that you have depression when you don't, you haven't actually been diagnosed with it, people will call you out and say, 'you can't just say you're depressed because you feel a bit sad. That's not fair on the people that are actually suffering from depression.' But if you get people saying, 'I'm so OCD, I like to colour coordinate my notes, I have to have everything lined up,' they might actually be OCD symptoms, but if you haven't been diagnosed and it's clear you don't have the condition, then it can be upsetting for people that do. I'm not saying people do this maliciously, but I think now as we have these conversations it needs to be something that we stop saying.

James - I think you are definitely right there. As you got older, did your OCD change in any way?

Patrick - The best way to describe it to you is that it shifted from the compulsions more into my head. It almost became more of a mental health issue because there weren't physical symptoms of it anymore. I wasn't tapping or checking. I admit, I think this probably came from a bit of shame. I didn't really want to speak about it when I was younger and I noticed that people noticed I was behaving in certain ways. I think I tried to stop and repress the compulsions as much as possible, but as you'll know, that's just not possible. It kind of went more into my head and it became more of a pure form where it just completely affected my thoughts and I had less compulsions, but it was stronger than ever really.

James - It's just this overwhelming feeling of powerlessness against the thoughts inside your head?

Patrick - Exactly, yeah. It's like my brain is blackmailing itself. It wasn't sure of where it stood in any situation.

James - How have you managed to manage the condition? Whether it be in those earlier years or more recently?

Patrick - To be honest, the best thing I did was to start speaking about it. I didn't know anybody else that had suffered from such a thing. I felt so different to everyone else. I'd heard of depression and anxiety, but I hadn't seen these symptoms in real life. It's only coming to Cambridge actually, when I first got here, that I found a lot of people were very comfortable speaking about the condition. That almost gave me the confidence to be like, okay, I'm not alone. It's from there that, for the first time, I could say stuff out loud, I could admit it to other people, to my friends and my family, without feeling I was different or I was strange. It was only these conversations that actually made me go and get help, go to the NHS and get cognitive behavioural therapy.

06:38 - Is OCD caused by a bias in the brain?

Is OCD caused by a bias in the brain?

Trevor Robbins, University of Cambridge

We need to try to understand what’s going on inside the brain to bring on these obsessions in OCD. Trevor Robbins is a professor of cognitive neuroscience at the University of Cambridge…

Trevor - The classical idea would be, intrusive thoughts are often very unpleasant and cause anxiety. In order to cope with this anxiety and reduce the stress, you perform this repetitive behaviour. It's a kind of a coping response. And there may be some truth to that, but the evidence isn't totally clear. It's interesting from a psychological point of view that we know that avoidance behaviour, for example, in the lab, often develops into what we call habits. Habits are more automatic and they no longer really depend on the original conditions which produce them. In other words, you might perform the behaviour initially to reduce anxiety, but then you just do it automatically and the anxiety is irrelevant then in the brain. There's a balance between your goal directed behaviour and habits. We think it's flipped over a bit to the habit system in OCD. That's partly why it becomes more automatic and less amenable to cognitive manipulation as it were.

James - Fascinating to hear the nuance and the active debate clearly on this particular condition. If we stick with the classical model for one minute, what's the psychological sequence of thoughts that leads some people to demonstrate the behaviours, the compulsions that we see? Because I think there's quite a few misconceptions on that topic.

Trevor - There's a lot, and OCD is expressed in a variety of ways, but the classical example really is germs: fear of infection. This leads to excessive hygienic behaviours, washing your hands so often with bleach that you actually cause damage. Then clearly it's a compulsive behaviour. Another classic example really is checking. Checking whether you've locked the door after you've left your house, maybe spending 15 or 20 minutes to ameliorate this anxiety that somehow your house is going to be violated in some way. Checking by the way is a very fundamental symptom in OCD. Even if you are afraid of germs, essentially you are checking all the time whether your skin is clean. OCD can often extend into other areas, for example, perfectionism and ordering, which is a more cognitive aspect. But again, checking is important there. Checking that the arrangement is perfect, checking uncertainty. Uncertainty is core to OCD. The issue I suppose is whether uncertainty causes inappropriate anxiety which is relieved in some way.

James - And these compulsions, they have, on the face of it, a practical and reasonable reason for doing something. Checking, for example, that you haven't left the oven on, that makes sense as something to do.

Trevor - Absolutely. In a sense, habits are obviously very adaptive and leading them into compulsive behaviour is also adaptive in some sense. As a scientist, I'm fairly careful and compulsive and checking, if you are proofreading for example, that's a skill that you have to develop, being very careful and checking everything is correct. In a sense, we all have a bit of OCD and what I would argue is that there is a dimension of behaviour called compulsivity which extends in very normal areas. For example, stamp collecting or something like that. But then gradually it becomes excessive and there is a point where this tendency to compulsivity is maladaptive because it stops you doing other things, for example, or you are not even doing the thing you wanted to do in the most efficient manner. It's really interfering with your life because you're spending all your time doing this behaviour.

James - It's interesting because one of the key frustrations I find having spoken to people with quite debilitating OCD is people describing themselves as a bit OCD because they like to keep their room tidy or because they engage in other sorts of behaviours. So I was interested to pick up on that.

Trevor - It's a major problem I think socially because OCD is stigmatised and that I think that has prevented large attention being devoted to it for treatments and so forth and research activities. This has to change because it's a very serious and disabling disorder in quite a large number of people. The incidence is 2 to 3% of the general population, which is enormous.

James - That's the kind of psychological grounding. This is manifesting in a wide variety of ways as we've described, presumably with a common neurological basis.

Trevor - Yes, indeed. I said earlier, one way of thinking about this is a bias towards the habit system in the brain from the goal directed system. There's a lot of brain scanning experiments in humans and experimental animals showing this dissociation between the systems. You can discern some of this in OCD patients, but I think there's a third factor. The third factor relates to the system which controls the balance between these systems in the frontal lobes of the brain, in the frontal cortex. We call this the arbitration system, and it's mediated by parts of the frontal cortex and the stratum, which seem to switch in whichever behavioural system is required. If this switch is a bit inefficient, then you're going to land up with habits. Compulsions aren't simply habits, they're habits which can't be regulated, which you can't inhibit. OCD patients also are a bit rigid cognitively. They're cognitively inflexible if you like. So that doesn't help either.

James - A lot of people who experience OCD will point to trauma earlier on in their life. Can you elucidate the detail as to why that might be related and where that fits in the psychology or the neurology as you've described it?

Trevor - That's a very interesting one. Trauma obviously is associated with stress. Really it comes back to what I was saying earlier that maybe you have to cope with that stress. You have to protect the brain, you feel anxiety as a consequence of the stress and you indulge in these compulsive behaviours in order to reduce the stress. That's the hypothesis. On the other hand, the other possibility is that something in brain development just goes slightly wrong and you find yourself repeating your behaviours. One idea we've had is that when that happens to you, that makes you anxious as well because you have to find reasons to explain why you're doing this weird behaviour.

15:12 - Interest in electrode therapy and psychedelics for OCD

Interest in electrode therapy and psychedelics for OCD

Camilla Nord, University of Cambridge

Once patients do get over the critical hurdle of diagnosis, effective treatments are out there, but it’s something of a mixed picture, hardly surprising given the evolving theories as to what the mechanism behind the condition actually is. Here to talk us through what we do know is Camilla Nord, who leads the mental health neuroscience programme of research at the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at the University of Cambridge. We started with the gold standard first-line treatment or OCD, cognitive behavioural therapy…

Camilla - In the context of OCD, cognitive behavioral therapy or CBT is a kind of talk therapy, but it's a little bit different than the way you might think about talk therapies. It's not dealing with your history and your family and where these things might come from. It's dealing with symptoms often in the here and now is how you can think about it. One aspect of CBT is the C - cognitions - that you experience. There you might work on why you have certain thoughts that emerge and perhaps reexamine, or it's called restructuring, those thoughts. Then particularly crucial in OCD treatment is the B part, the behaviours. Even if you don't experience compulsions as some people with OCD don't, actually, the behavioural part of CBT is really crucial because this often involves exposing you to the very things that you're having intrusive thoughts about. Working on those reactions often little by little, starting with something at the minor end of what you're having intrusive thoughts about and working up to maybe a more realistic setting of what you experienced day to day.

James - Say your obsession was over germs and health. By exposing you to unhygienic scenarios and the result being that you are okay, you overcome the fear of the germs and realise that no significant harm came to you.

Camilla - Yes, exactly. So if you're particularly worried, for example, about germs on something that you're about to eat, you might work your way towards eating it, starting with maybe handling it and observing, experiencing that you don't become sick, you don't have consequences from that. I think I remember one context of a therapist not washing their hands after the loo and then touching a biscuit. We can all imagine how that might be a bit gross, but for someone with OCD that is a prohibitive, intrusive thought that they might have and that might lead to the kind of compulsions that they experience. And so working up to maybe even being able to eat that biscuit.

James - Well, let's hope for their sake that it is effective. But as I understand it, CBT works for 75% of people. So that still leaves a significant portion who persist with their symptoms even after cognitive behavioural therapy.

Camilla - Yeah. And I should say that's 75% for whom it works a little bit. So they have a response to it, which would mean a noticeable reduction in your symptoms. But even in that 75%, there will be a substantial number of people who have some residual symptoms. It doesn't necessarily make them totally go away.

James - Okay. And on top of that, is the point that the waiting list to see a psychiatrist is very long.

Camilla - That presents a challenge because for that 25% who don't experience really any noticeable change in their symptoms, there are other strategies that exist, but they might be difficult to access. For example, some people respond very well to the high dose of antidepressants, the most common class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs. But with that, you would want to be working with a medical doctor to work out the right dose for you, ensuring that you don't have side effects and so on. Sometimes those can be used in combination with CBT and it actually helps you access the CBT to have that pharmacological intervention. It achieves the goals of the psychotherapy that it might not achieve on its own.

James - As we've been hearing, there's an active debate as to what the mechanism of the disease actually is or the condition actually is. Is OCD caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, perhaps? And that would make sense as to why SSRIs would be effective. Or perhaps it's a bias towards a certain brain network, the habit network and against the goal directed system. Because depending on that answer to the question of what the mechanism is, the treatments might be different?

Camilla - I'm not sure that I agree that the treatments would be different depending on whether you think of it as a chemical imbalance or not. I don't think of OCD as a chemical imbalance. I think many neuroscientists don't. Brain networks, it might not even be exactly the same change in every patient. Nevertheless, we use lots of drugs for things that aren't just a deficit in that problem. Paracetamol works without you having to have a deficit in the specific thing that paracetamol is targeting. I think SSRIs have properties that can change brain networks, and so it's sensible that they might be working in OCD without necessarily curing some sort of decrease in a brain chemical.

James - Tell me about the interest in deep brain stimulation at the moment and its potential perhaps in curing OCD or alleviating the symptoms.

Camilla - Deep brain stimulation is a treatment that originally comes from Parkinson's disease. The way that it works is, surgically, neurosurgeons implant electrodes deep in the brain, in the structures that we know to be involved in OCD. Then by delivering electrical currents to those regions, it can change the biasing of brain networks in a direction closer to people without OCD. Whether or not it works in OCD was something that has now been explored in a couple of big studies and there does seem to be effectiveness, but I think the problem, or I suppose the challenge with deep brain stimulation is you have to get the target right. There we get back to the idea of, does everyone necessarily have the same region that should be targeted overall? These are patients who don't respond to anything else. This intervention works in, I think, more than half of them, over 60%. So that is still a really useful and effective treatment. But I would say that, in the long run, for most patients with OCD, they might not be candidates for something as risky as neurosurgery, but there might be other ways of changing those brain networks, for example, with non-invasive brain stimulation.

James - Quite. And to go one step further, what about something like a psychedelic treatment? I know there's obviously lots of interest in psilocybin and ketamine for treatment resistant depression, the theory being that they encourage the growth of connections between systems in the brain. So why couldn't the same be true for OCD potentially?

Camilla - Yeah, you're right. The interesting thing about ketamine is, in OCD, like in depression, SSRIs take a really long time to work, and yet ketamine in depression is a rapid acting antidepressant. So it's very effective for many patients and it works quite quickly. That would be incredibly useful for people with OCD to have more immediate relief from these very debilitating symptoms. In many cases, the jury is still out. I think there is probably a little bit more work that's been done now on ketamine than on, say psilocybin, which I think is truly ongoing, because you really need things like a robust placebo group working at the level of, is it this specific, or is it your expectations of getting better, which are incredibly powerful unconscious drivers of treatment response in many cases.

24:04 - The gut microbiome and OCD

The gut microbiome and OCD

Stephanie Fitzgerald, University of Cambridge

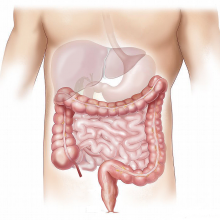

We’re going to move on from looking solely at the workings of the brain in relation OCD, and incorporate the growing body of research into the body’s so-called second brain: the gut microbiome. It’s no doubt a very trendy topic, with so much ongoing research into how the diversity in the species of the 100 trillion bacteria in your gut can impact all facets of our health. Here to provide the picture as relates to OCD is clinical psychologist Stephanie Fitzgerald…

Stephanie - The reason people started to talk about the second brain in the gut is because the same chemicals that are found in the brain are also produced in the gut. So for example, serotonin, the availability of those chemicals to the brain can be governed by the activity of the gut bacteria.

James - One of the mainstream treatments for OCD is SSRIs, serotonin reuptake inhibitors. So obviously crucially important if a significant portion of the serotonin in our body is residing in our gut.

Stephanie - Yes, absolutely. There's a precursor to your serotonin, a necessary precursor, which is tryptophan. Your levels of tryptophan in your body are very tightly governed by your gut bacteria. Even if you are taking a medication to enhance or promote serotonin, if your gut bacteria aren't healthy, if your gut microbiome isn't healthy, then actually you may struggle to get the full benefit of that medication. Even if you're taking something very specifically focusing on serotonin. It's very similar to if you've taken an iron supplement, but your vitamin C levels are low, actually you're going to struggle to get the benefit of that supplement. It works in the same way. If you're taking serotonin, but your tryptophan levels are out, you're not really going to see the full benefit of that medication.

James - Tell us about the gut and its role in mental health, perhaps in terms of potential mechanisms.

Stephanie - If we think about it more broadly, our microbiome also affects our mood, our libido, our metabolism, our immunity, our perception of the world, and the clarity of our thoughts. So if we think about, for example, depression and anxiety, we know that whether we feel full of energy or demotivated or very lethargic, these things can really show up as symptoms of depression or anxiety. Really our microbiome could be said to control every aspect, or certainly contribute to every aspect of our mental health and how we feel physically as well as mentally.

James - If we think about OCD, the compulsions that people exhibit are as a result of their stress response. Does what you are saying here have any part to play in that story?

Stephanie - Yes, absolutely. Really it all comes down to inflammation and gut permeability. High levels of inflammation in the gut dramatically increase that risk of developing depression and anxiety. If we think about OCD and symptoms, the higher the inflammation in the gut, the higher the level of anxiety and symptoms you are likely to experience. There's quite a bit of new research which is suggesting that some antidepressants, for example, actually target inflammation in the gut now rather than directly impacting the brain. So the acknowledgement is if we soothe and calm this inflammation in the gut, we're going to reduce symptoms. The thing with OCD is obviously is it's an anxiety disorder. The anxiety response runs on the same mechanisms, if you like, as the stress response and your gut microbiome and the levels of inflammation are going to affect your stress response. They will also affect your reactions in stressful situations. So those compulsions won't necessarily go away, but the distress that they cause, the level of anxiety around having to do them in a certain way at a certain time, that can be managed by a much calmer gut.

James - Maybe we've fermented some inspiration in our listeners, Stephanie. What are the foods we should bear in mind when we're trying to keep our gut healthy?

Stephanie - It's a great question, and what I will say is that it doesn't need to be expensive. I would always encourage people to start supporting their gut health with a simple probiotic supplement. But actually beyond probiotics, it's looking at things like live cultured yogurt, for example, things like kefir, which is a fermented dairy product. Things like kombucha tea, again, it's a fermented tea. It's slightly fizzy. You serve it chilled. It's quite easy to make yourself. And then more broadly you want to have a very varied diet that's good for your gut. We do have this sort of good food for good mood guideline where you know lots of vegetables and a good variety of vegetables. Your plate should look quite appealing and quite colourful. That's a really good way to see, am I eating something that's good for my mood? If you take something like chicken and chips, that's a very beige meal. There's not a huge amount there that's good for your mental health. But if you look at a chicken salad, suddenly you've got all those colours on the plate and you think this is doing me some good.

Comments

Add a comment