In this NewsFlash, how box jellyfish navigate by seeing the shape of the objects above them, why researchers have trapped anti-hydrogen for an extended stay and how a changing climate has reduced global corn and wheat crops. Plus, how the very first exposure to nicotine causes changes in the brain's reward system, potentially strengthening future addictions.

In this episode

00:17 - Climate change has affected crop yields

Climate change has affected crop yields

This week researchers from Stanford University have revealed that, in the last 30 years, corn and wheat crop yields have dropped by 3.8 and 5.5 per cent in response to climate change. This decrease in production has occurred in spite of technological advances, pest control measures and the use of fertilisers...

Publishing in Science, David Lobell and his team note that all major growing regions for wheat, maize, soybeans and rice have experienced increases in temperature since 1980. The notable exception was the US, which experienced cooling. And, although corn and wheat have seen a drop, soybean and rice crops have remained roughly unaffected across the globe.

To reach their conclusions, the researchers developed two models: one which mimicked the observed increases in climate temperatures; and one which assumed temperatures had stayed the same since 1980. They also used statistical tests to see if precipitation changes affected crop yields. The results demonstrated that increases in temperature had reduced global yields of wheat by 5.5 per cent, and increased rainfall also had a negative effect on crops but it was much less marked than temperature.

Given that the U.S. is a notable exception, it shows that analysing climate change data on a country-by-country scale will be misleading. This team have shown that temperatures in the United States haven't increased in a statistically significant way, and subsequently their crops haven't suffered. But the rest of the world has seen a very obvious and worrying change. And this doesn't mean the U.S. is unaffected, since decreases in food availability across the world will inevitably have an effect on the cost of imports. In fact, the authors argue that it already has.

02:53 - Box Clever: jellyfish use eyes to navigate

Box Clever: jellyfish use eyes to navigate

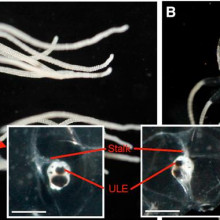

At just one centimetre across, the box jellyfish - Tripedalia cystophora for lovers of Latin - makes a poor contender for being a paragon of intellect. But now  new research has show that these tiny creatures can actually navigate by following the outlines of objects in the sky above them.

new research has show that these tiny creatures can actually navigate by following the outlines of objects in the sky above them.

The jellyfish live in-shore among the roots of mangrove trees where they prey upon tiny light-loving plankton species that gather in sunny spots along the margins of the swampy surroundings. But if they wander too far from the shoreline and away from their food source, the jellyfish risk starvation; consequently they are rarely found out in open water.

So how do they avoid being swept away?

University of Copenhagen scientist Anders Garm and his colleagues suspected that the jellyfish might be making use of the 24 "eyes" that adorn structures called rhopalia on each of the four sides of the animal's box-shaped body. Surprisingly, two of the eyes in each rhopalium, one looking up and one looking down, actually use a lens system similar to our own to focus light.

To find out what this upward-gazing eye might be capable of seeing, the researchers used a wide-angle lens to take photographs from just below the water surface. The pictures reveal that, owing to the way that water causes light to bend or refract, each eye would be capable of surveying a 180 degree field of view. And from distances of up to 8 metres away, the outline of the mangrove canopy against the sky would be clearly visible to the jellyfish, providing them with fixed reference point to keep them close to home.

Working in a mangrove swamp in Puerto Rico, the researchers then tested the theory by placing locally-caught box jellyfish into a floating, circular open-toppped tank that was partially submerged in the seawater. This meant that the animals could see the sky, and the overlying trees, but were isolated from any water-borne chemical cues that might provide navigational aids.

The researchers then slowly moved the tank different distances away from the shore and watched the movements of the jellyfish. Incredibly, at distances up to 8 metres, they all swam towards the shore-facing side of the tank. At distances greater than 8 metres, the animals moved randomly again, consistent with having lost the visual reference of the treeline, just as the underwater photographs had predicted.

The team don't know exactly how this intelligent photaxic behaviour is achieved but they speculate that it could be a neurological adaptation of a solar compass. The animals actually lack brains, although each rhopalium carries an associated nerve ganglion equipped with 1000 neurones, and a "ring nerve" links the four ganglia, presumably helping to coordinate the animal's response to what its eyes are seeing.

But regardless of how it works, as the team point out, their observations "defeat the idea that a central brain is a prerequisite for advanced behaviour."

06:13 - Antihydrogen trapping

Antihydrogen trapping

Every particle we know of has an anti-particle, so there are anti-electrons, anti-protons, anti-neutrons etc. These seem to behave pretty much the same as their normal relations, but they have the opposite charge, and if an anti-electron meets an electron they anihilate completely releasing a huge amount of energy in the form of photons.

Physicists don't understand why there is far more matter in the universe than anti-matter, so they would like to study anti-matter to understand it. The problem is that the only way to make it is in violent collisions so it is enevitably moving very very fast, so you don't get a lot of time to study it, and whilst you can slow down charged particles magnetically, if you want to study the details of anti-atoms slowing them down is much more difficult

Physicists don't understand why there is far more matter in the universe than anti-matter, so they would like to study anti-matter to understand it. The problem is that the only way to make it is in violent collisions so it is enevitably moving very very fast, so you don't get a lot of time to study it, and whilst you can slow down charged particles magnetically, if you want to study the details of anti-atoms slowing them down is much more difficult

In November researchers at CERN managed to trap 38 atoms of antihydrogen for a maximum about 0.2 seconds. Now they have managed to trap over 300 antihydrogen atoms for a maximum of 1000s or about 17 minutes.

They are now moving onto studying the anti-hydrogen, looking very carefully at the energy levels in the atoms, and possibly even finding out whether anti-matter is attracted or repelled gravitationally by ordinary matter

08:29 - The Brain's First Whiff of Nicotine

The Brain's First Whiff of Nicotine

Professor Daniel McGehee, University of Chicago

Chris - A new study sheds more light on how the brain responds to its first ever whiff of nicotine. By looking at activity in the brain tissue of a rat as it's exposed to nicotine for the very first time, Professor Daniel McGehee, at the University of Chicago, has found that the drug triggers changes in the brain's circuitry, which makes people much more likely to then get hooked.

Daniel - The dopamine system is this reward pathway. The effect of addictive drugs on behaviour is dependent on a change in dopamine signalling, so that's been a focus for our work and many other groups. We know that dopamine activates a specific type of receptor, a protein that's on the surface of many different neurones. And these receptors are excitatory - they depolarize the cell, causing it to fire more so more electrical activity occurs - and we know that that's the first step in the process. What our most recent study has shown is that this actually initiates a whole cascade of events. One of the things that happens is that the inputs that normally excite these dopamine cells become stronger. The synaptic connections - the points of connections between cells - are stronger after nicotine exposure.

Chris - So are you saying that the nicotine comes in, it stimulates some dopamine-producing nerve cells to make more dopamine, which the brain experiences as being a pleasurable experience, and at the same time, the cells that make that dopamine, which are connected to other nerve cells, begin in future to respond more strongly to those connections than they would have done before?

Daniel - That's a nice description of what our data and others have shown, yes. The connections are stronger and this is something that persists for days. What we're looking at is the steps that lead to that change. Even after the nicotine is gone, these connections remain strong for between five and ten days after exposure, and just to emphasise, that's a change in an animal that has not seen the drug before and it's in response to one exposure.

Daniel - That's a nice description of what our data and others have shown, yes. The connections are stronger and this is something that persists for days. What we're looking at is the steps that lead to that change. Even after the nicotine is gone, these connections remain strong for between five and ten days after exposure, and just to emphasise, that's a change in an animal that has not seen the drug before and it's in response to one exposure.

Chris - And when the person has had that change happen in their brain, what then makes the person keep reaching for the cigarette packet? Because if their cells are now producing more dopamine because the connections to them are stronger - the cells are getting more excitable than they were before - then why carry on smoking?

Daniel - Yes, that's a great question, and one that we would love to have a complete answer to. The transition from occasional use or a single exposure to the full-blown addicted smoker is a long and complex process that we really don't understand. We know that there are huge adaptations happening in the brain areas that we're looking at, but it's also very likely that other brain areas play critical roles. In adolescents who are experimenting with smoking, they will quite often sample cigarettes at a very low rate, like once a month, once every two weeks etc. One theory that I like is the idea that the duration that this increase in excitation in the pathway persists for is contributing to that process and establishes a framework for associating the tobacco and nicotine with pleasure, and that basically sets the stage for the progression to full-blown addiction. The progression is going to be involving this process but also almost certainly other processes that we don't yet understand.

Chris - Does it transfer to other drugs? Because if you rewire this circuitry which makes your brain much more prone to getting hooked on things, and then another drug comes along, does the tobacco pre-priming mean that some cocaine is much easier to get hooked on that it would be without this happening?

Daniel - That's certainly a possibility. It's beyond the scope of what we're looking at right now, but co-use of a variety of different substances is quite common, so the idea that exposure to one drug modifies or enhances the rewarding effects of another drug makes perfect sense to me, as far as I understand the system, and this could be one of the ways in which that could happen.

Chris - I think 75% of smokers say they would like to quit - that's the intended quit rate - though the successful quit rate is another matter. What about using this information to help people to quit or to not get hooked in the first place?

Daniel - I do think that this adds to the public health message that I think is being broadcast quite effectively in many parts of the world - that exposure to tobacco products and nicotine is potentially addictive and long-term exposure has hugely negative health consequences, and there's just no argument here. Even occasional and casual use of tobacco products could be inducing persistent effects on parts of the brain that we know are involved with reward and addiction. As far as the potential for treatment of the full-blown smoker who is trying to quit, we certainly hope that identifying steps in the process, in terms of cellular events and molecular events that are happening inside neurones, may lead to the identification of new drugs that will improve the abysmal quit rate that's out there. I do think that the most important message is that there are changes happening with the very earliest exposures, and they are part of the progression to full addiction.

Chris - Well they say that it only takes one cigarette to get you hooked, and that evidence does look compelling. That was Professor Daniel McGehee, from the University of Chicago - he's published that work in the Journal of Neuroscience this week.

Using antioxidants to combat radiation poisoning

This week, researchers from The University of Pittsburgh have found that a chemical similar to that found in red wine can protect against radiation sickness.

Specifically, they looked at gamma (γ) radiation and how its effects might be reduced by a substance similar to resveratrol. Resveratrol is an antioxidant commonly found in wines, grapes and nuts; and plants commonly use it to fight off bacterial or fungal infections. The reason the researchers think that an antioxidant might help in protecting against radiation exposure is that they 'mop-up' the free radicals that gamma radiation can produce. And it's these ionised free radicals which do the cell damage.

Specifically, they looked at gamma (γ) radiation and how its effects might be reduced by a substance similar to resveratrol. Resveratrol is an antioxidant commonly found in wines, grapes and nuts; and plants commonly use it to fight off bacterial or fungal infections. The reason the researchers think that an antioxidant might help in protecting against radiation exposure is that they 'mop-up' the free radicals that gamma radiation can produce. And it's these ionised free radicals which do the cell damage.

Publishing in ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters, Michael Epperly and colleagues first tested the naturally-occurring resveratrol on live cells in flasks, which were exposed to radiation. They found that these cells were given some protection by the chemical but, when they tested it on a mouse, it had very little positive effect. So the researchers turned to another, similar chemical known as acetyl-resveratrol. This time, the drug produced an eighty per cent survival rate amongst the mice. The difference between the two drugs efficacies is most likely because acetyl-resveratrol is more slowly metabolised and therefore lasts longer to provide its protective effects.

And the authors also argue that this could be good news for cancer patients, since the other candidates for anti-radiation drugs work by suppressing cell apoptosis (that is, cell death) and could therefore aggravate a cancer. Because they think acetyl-resveratrol is using a different mechanism, it could be a better alternative and, they add, it is relatively cheap to produce.

16:40 - Space Dragging Confirmed by Gravity Probe B

Space Dragging Confirmed by Gravity Probe B

In 1918 two Austrian physicists worked out that if Einstein was right any large spinning object should drag space and time around it. So if you are near the spinning object your idea of not spinning should be different to the idea of someone in deep space.

The problem is that although this would be quite noticeable if you were near to something very heavy spinning very fast, there is nothing nearby that is heavy enough to make a large effect. Near the Earth the effect should only be tiny.

This is such a big problem, in fact, that the project to measure this effect has taken 52 years, and produced a satellite called Gravity probe B. This is an incredible mission using some of the most outstanding physics out there.

This is such a big problem, in fact, that the project to measure this effect has taken 52 years, and produced a satellite called Gravity probe B. This is an incredible mission using some of the most outstanding physics out there.

Basically, it involves incredibly smooth spheres covered with a thin layer of superconductor spinning very fast and acting as a gyroscope.

If there are no external influences, these should keep pointing in the same direction. The satellite detects their direction using superconducting sensors called SQUIDs and compares them to a fixed star. The whole thing has to be cooled to make sure the superconductors work, and minimise thermal noise; to reduce friction, it is cooled using superfluid liquid helium, which has no viscosity, minimising its effect on the gyroscopes.

The satellite was lauched in 2004 and took measurements for 18 months until the helium ran out, it has then taken about 5 years to analyse the data properly, coming out with a figure of about 10.3 millionths of a degree per year for the frame dragging effect, which compares well with 10.8 millionths of a degree per year which relativity predicts. They also found a very good agreement for a second effect called geodetic precession.

These not only show how good Einsten's theories are, but allow astonomers to improve their models of heavy objects like neutron stars and black holes.

Related Content

- Previous How do we keep warm?

- Next Should I Lie Down to Tan?

Comments

Add a comment