Palaeo Ponderings: Can You Dig It?

Did dinosaurs live in herds? Why are mountains pointy? And what's the best preserved mummy? Plus we had a giant snake, a few skulls, a couple of “feet” and one of the oldest rocks on Earth in the studio. Scientists Lee Berger, Meghan Strong, Jason Head, and Owen Weller team up for an Early Earth Q&A show.

In this episode

02:57 - What did the Egyptians have against alphabets?

What did the Egyptians have against alphabets?

Egyptologist Meghan Strong, from the University of Cambridge, showed Chris Smith her hieroglyph dictionary and took on this fitting question from Matt in Melbourne...

Chris - I see you have a very useful text in front of you because you’ve brought a dictionary.

Meghan - I have. This is a very well-used, well-loved dictionary that was one of the first textbooks that I got as an Egyptology student and it’s sort of a bible for me really. Ancient Egyptian is a language that was written down and hieroglyphs is one of the scripts that was used to record it. It is one of the oldest that we know of.

Chris - When does it date from? Does it literally go right back to our earliest records of ancient Egypt?

Meghan - The earliest evidence that we have for simple hieroglyphs being used was probably about 3300 BC so that’s quite a way back. That’s into the very, very beginnings of dynastic Egypt but not up to the point of of pyramids, which most people think of.

Chris - Matt slightly provocatively said “what did the Egyptians have against alphabets and things?” How do hieroglyphs work, is it like Chinese characters where there are sounds? How does it work?

Meghan - Yeah. Hieroglyphs can work in several different ways. The Egyptians did have characters that could function as what we would recognise as an alphabet, so you can spell out people’s names for example - that’s very useful. But they could also stand for sounds so something that we would think of like a syllable, a single hieroglyph could stand in for that. Or you could also have hieroglyphs that would stand on their own as an individual object. so you can have a picture a goose, and that would stand in for the word “goose”.

Chris - How do people decode them in the first place?

Meghan - Most people would say that this goes back to Champollion, and the discovery of the Rosetta Stone was the real watershed moment. People have been working on the decipherment of hieroglyphs from the medieval period, but when the Rosetta Stone was found, that really allowed people to crack how you read hieroglyphs by comparing it to Greek.

Chris - So that gave: this is a Greek piece of text; this is the equivalent in hieroglyphs and so people could begin to get some insights into how the language was constructed?

Meghan - Exactly. The Rosetta Stone is recorded - it has three different languages on it. One of them being Greek, one being Demotic which is another script used to write ancient Egyptian, and then formal actual hieroglyphs.

Chris - Why did someone go to the trouble of writing that? What was the point if these languages were around at the time and they could speak all of them, which they clearly could, why make that tablet?

Meghan - Yeah, it’s a good question. I think at the time the Rosetta Stone was found in the Nile delta, and this was an area that was ruled by the Greeks at the time and so Greek, obviously, being a language that they would recognise. But ancient Egyptian being the language of the country and still being used quite heavily for monumental inscriptions, which is what the Rosetta Stone was.

Chris - Can you read hieroglyphs now thanks to your dictionary?

Meghan - I can, yes, thanks to the dictionary.

Chris - Can you really? So when you look at these things you can actually read it too?

Meghan - That is one of the cornerstons of Egyptology: you have to be able to read your hieroglyphs!

Chris - How long did it take you to learn?

Meghan - Well, there’s different phases of the language. Initially, to get your grounding it takes a good solid year and then you have to build up from there different phases.

Chris - That’s extraordinary to think that before you can actually begin to study something archaeological you have to learn a whole new language in order to do that!

Meghan - Yeah, absolutely. And sometimes multiple, depending on the period.

Chris - It’s a good selection process I suppose: it's only the fittest survive!

Meghan - Those who are dedicated.

Chris - Darwin would approve!

Meghan- Yeah, absolutely.

06:32 - Did fire make our ancestors lose their fur?

Did fire make our ancestors lose their fur?

Chris Smith put this question from Colin on the Naked Scientists forum to human origins expert, Lee Berger. Dinosaur expert Jason Head, from the University of Cambridge, then explained how dinosaur skin wasn't quite as crocodile-like as is often depicted...

Lee - I think the first part is what’s the difference between fur and hair? We often speak of humans as having hair and animals as having fur, and the answer is nothing, it’s the same thing. It’s a semantic argument. But the early part of our understanding of where we see a sort of "fining" and separation of hair in humans is probably at the root of that question, and we kind of tie it to two things. One is thermoregulation - the idea that we need sweat glands. We sweat on our skin to actually lose heat. We believe that happened with long distance walking and running, and this longer limb period is generally associated with the origin of the genus Homo. So the answer is maybe it was associated with the fire because those two things go back a very long way. Fire, the oldest fire that we’ve got is about 1.3 to 1.5 million years. It’s surprisingly hard to see in the fossil record, but that morphology, that wider chested, long-legged anatomy that signals sweat glands maybe 2 million years ago, but we don’t trust these dates these days. We keep finding something every other week that pushes something further back or in a different line!

Chris - We take for granted our access to fire in the modern era, but what would it have taken for ancient ancestors of humans to have mastered the art of fire making, and nurturing, and using fire to good effect?

Lee - Well, having spent the last several years down a deep dark hole looking at homo naledi fossils I’ve pondered fire a lot, and the idea of fire as both a heating source but also as a light source to move into these more remote, underground chambers. Fire is a tricky thing - most animals hate it. They hate it instinctively if you’re a terrestrial animals for very obvious reasons, fire is a very scary thing.

At some point in our past, and that is somewhere in our very distant past. A million and half, two million maybe, I would suspect even further than that, part of our family tree began catching fire, and catching fire is probably a first key to that. Manufacturing fire, we don’t really have any evidence of until the last several hundred thousand of years. And generally the early parts of that are controversial in of themselves because there’s a big difference between catching fire in the wild after a lightning strike or some event like that and then tending it for long periods, and manufacturing it.

Anyone who’s ever tried to use crude implements to actually manufacture fire would understand that there’s a great technologically leap and also maybe a mental leap that would have may have occurred a little later in our timeline.

Chris - Indeed. Someone who’s tried to make a fire in a camp the traditional way, it takes quite a bit of dedication, doesn’t it!

Lee - Extraordinary.

Chris then received this question from Sarah on Twitter...

Chris - Sarah Davey who wants to ask you, Owen, as a geologist, do you have a favourite rock?

Owen - I do. that rocks called a Blueschist and, as the name suggests, it’s a very vibrant, blue colour. Not only are they very attractive to look at in the field, they are also very special rocks because they tells us that there was an ancient subduction zone at that locality, so that’s where one plate goes underneath another.

Chris - What are they made of?

Owen - They’re made of principally a mineral called glaucophane [Na2(Mg3Al2)Si8O22(OH)2] and this has a very, very distinctive blue colour which gives it a very simple name, the blueschist.

Lee - I had a pet rock.

Chris - Go on…

Lee - Everyone who wants to get into geology has a pet rock when they’re a kid and so I had one. I lost it though and it’s been sad ever since.

Owen - Oh, your life could have turned out very differently.

Chris - Imagine what you could have been if you’d still got that pet rock today.

But what about dinosaurs?

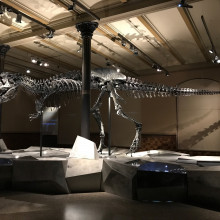

Chris - Interestingly, Jason, because Lee’s saying about our ancient human ancestors losing their hair but what about dinosaurs? What were they covered in because if you go to museums and things you see many specimens of dinosaurs and they show things with skin a bit like a crocodile, but they’re not exclusively like that are they?

Jason - That’s actually a really interesting question and there’s a lot of research being done on this issue right now, and there's’ a lot of controversy. From certain parts of the geologic record you have particular environments where you find fossils that actually preserve the impressions of soft tissues. With certain dinosaur groups, when we find those impressions, they often include integumentary structure that look kind of like hair. They’re almost quill shaped and they’re often called “protofeathers” because they have kind of a feather like appearance to them.

So right now there’s a big question as to when do these protofeathers first show up in the history of dinosaurs? Is this a feature that all dinosaurs have primitively at the origin of the group, or is this something that’s evolved once or more than once very high up or higher up in these nested groups within dinosaurs? Certainly, by the time we get to true birds, things like archaeopteryx, then we see these well developed flight feathers and so we know what they’re covered with. But whether or not T. Rex, for example, Tyrannosaurus or any of the larger sets would have had an overall covering and integument or feather-like structures, it’s a little more poorly understood.

Amazingly for some animals like velociraptor, a small maniraptoran that’s risen to fame through the Jurassic Park films, we know they actually had probably elongate feathers running down the undersides of the arms because we’ve found specimens that have feather quill spots on the bone.

Chris - Do you think that the dinosaurs could have evolved to have feathers in order to conquer new patches of the Earth, to access new bits of the Earth which would have previously been a bit cold for them, and having feathers enabled them to access and use those areas? Because there’s populations of dinosaurs - and therefore competition went up in warmer spots - the choice spots were taken, so this enabled them to go into further reaches because it gave them insulation?

Jason - It’s possible, although the initial function for these feather-like structures is not 100% known. They may have functioned as insulation for the animals but also, where we find them on these well-preserved specimens, they’re actually quite patchy along the body, so they’re not presented on the animals as being a complete covering to keep them warm. These patchy distributions suggest that maybe what they were being used for was actually communication. That they could have had colour cells in them and they could have functioned as a form of display.

Why are mountains pointy?

This question was sent in by Paul ia the Naked Scientist forum. Chris Smith put this to geology expert, Owen Weller, from the University of Cambridge.

Owen - Once you’ve had some kind of rock uplift the shape or morphology of a mountain is simply controlled by the principal style of erosion at the particular locality. So to generate pointy peaks or, as they’re more formally known, pyramidal peaks, you have the process whereby you have three or more glaciers which are diverging from a central point under the influence of gravity and this leave behind the pyramid. This has given us such iconic peaks as the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc, Mount Everest and, conceptually, this is how most people view mountains, sort of in their mind's eye they see these pyramids.

However, I should point out that not all mountains are pointy.

Chris - I was just saying Lee’s adopted homeland, of course it’s South Africa. If you go to Capetown you see a very famous flat top mountain. It’s called Table Mountain for a very obvious reason.

Owen - Absolutely.

Chris - How did that happen?

Owen - It’s wonderfully named. Table Mountain is composed of flat lying sedimentary rocks, and it’s actually capped by a particularly resistant type of sedimentary rock called a Quartzite. So what happens here is that you get erosion that preferentially weather out underneath the top lying Quartzite, which leads to failure at the edges, so you get steep sided cliffs and a flat lying top.

Chris - Talking of pointy things and permeable in structure because this is your bag isn’t it Meghan. How did they actually come up with the shape of the pyramids? What was their inspiration - do we know?

Meghan - The idea is in one particular creation method in ancient Egypt that Egypt evolved from this mound of Earth that came up from this watery void of chaos called Nun, and this original mound of earth is thought to have been shaped similar to a pyramid. So the idea is that pyramids are a way of recreating that original sort of mound of creation.

14:36 - Is it common to find a variety of dinosaur bones?

Is it common to find a variety of dinosaur bones?

Chris put this question from James on Facebook to palaeontologist Jason Head, from the University of Cambridge, and Lee Berger from the University of Witwatersrand. "Are they served up beautifully on a plate, one specimen, all in one place, easy to sort out or is it a bit of a mess that you have to try and unpick?"

Jason - It’s a bit of both and it all has to do with physically where the animal dies, and what are the various way in which it enters into the rock record and so you have different kinds of what we call “depositional environments.” These are areas where the sediments that form the rocks the dinosaurs are in are actually physically accumulate. For some of these environments you can have an animal effectively follow and be completely buried and then you have a very well-preserved articulated skeleton.

In terrestrial environment, more often than not, what you have is an animal die and then you’ll have some kind of water action that takes the remains and transports them into basically a river system or a lake system. In that case, yeah, you generally do find a jumble of bones from different dinosaurs or different animals, so you get a lot of disarticulation. You have different kinds of preservation as well where certain bones will be exposed in weather on the surface before they then get transported and buried.

So yes, it is very common. It’s more common than not to find multiple types of dinosaur bones mixed in together.

Chris - Is that your experience Lee?

Lee - Yeah. Ours is a field where, particularly when we’re looking for human ancestors, we find them one by one. Up until recently, the story of paleoanthropology was probably in excess of 90% of the entire record was made of isolated teeth or isolated small bone fragment. That’s exactly the situation of an animal dying on the surface and going about the usual process in Africa or elsewhere where it’s eaten or dragged apart and disintegrates.

More recently though, we’ve been very fortunate both on terrestrial deposits, but also in these underground cave environments, finding more and more complete specimens. We have complete skeletons like Little Foot skeleton in South Africa, an australopithecus, but we’re starting finally to find deposits in more extreme, more protected environments where we have more and more complete specimens and we’re able to put individuals together. We can do like these hands I’ve got here; that hand was found curled up just like that, just in a death grip.

Chris - This is a replica of Homo naledi isn't it, your most recent specimen that you've uncovered at the Rising Star system near Johannesburg? And the amazing thing about the work that you’re now doing is, unlike historically, where you’d find a specimen like this and then you’d study it and it would be your sole preserve, now you’re scanning these things and 3D printing them to produce a sub-millimetre precision thing a bit like that, which you can then share round the world and a scientist anywhere could then begin to work on your specimen?

Lee - Not only can we - we do. If you go onto morphosource.org you can download any of our fossils and 3D print them yourself in your local 3D printer in your library...

Chris - A DIY Homo naledi?

Lee - … or home, and they are accurate to just a few microns of the originals and it doesn’t have to be a scientist. In fact, the tens of thousands of downloads we’re getting from school children are people who just want to have a hand.

Chris - And give you a hand, as well!

17:58 - What was the purpose of the Pyramids?

What was the purpose of the Pyramids?

with Meghan Strong, University of Cambridge

Having talked about searching for dinosaur bones and our ancient human relatives burying each other, Chris Smith asked Egypotologist, Meghan Strong, about the ancient Egyptian burial process.

Chris - And Meghan, it wasn’t just dinosaurs that got mixed up together, the Egyptians were pretty good at burying people, that’s what the pyramids were all about. Isn’t it, or wasn’t it.?

Megan - Yeah, absolutely. And I have to add in that we have just the same amount of problems in Egypt of putting together complete mummies and skeletons as well because the tombs have been lived in more recently, and even in ancient times they were reused many, many times over. So you frequently have people who do not go together and bits and pieces of mummies that you can’t quite figure out how many skeletons you have in one tomb.

Thankfully, with pyramids, they were intended to serve for one individual, particularly the king, sometimes queens. They were primarily restricted to kings and queens of the old kingdom as well so this is a very early period in ancient Egyptian history, so about 2600 to 2100 BC we’re talking about and they were intended to be the burial structure. This was their final resting place.

Chris - But they didn’t just put themselves in there, did they? Because is it not the case that very often the other servants or other people who would have worked on the structure itself ended up being buried there too?

Meghan - Not within the pyramid itself, no. For example, at Giza, there are the main three pyramids: those were the ones designated for kings. There are smaller pyramids: those were for the queens. And then there’s an entire separate cemetary for people who actually worked on building the pyramids themselves, that they had their own separate cemetery, their own graves. Some of them more elaborate burials as well. But no, they weren’t actually mixed in together in the same idea and the same place.

Chris - But were they voluntarily intered or were they involuntarily intered? So having worked on the structures was it regarded as a real privilege for them to die alongside the person they were building the pyramid for?

Meghan - It’s not the same idea as servant sacrifice. These workers yes, they had an incredibly hard, backbreaking labour that they needed to be part of an order to build these structures. However, it was something that was well-compensated, so you had living quarters while you were there, you were fed well. There’s a fair amount of evidence that they had an incredible amount of meat that was brought into the site. Bread to beer, which was their staple drink for the time. And there’s even evidence that people who broke bones or even had traumatic brain injury for example, they had surgeons on site to heal them.

Chris - Were they any good at brain surgery?

Meghan - Well, they did actually live on a bit afterwards. There is some skeletal regrowth there, some cranium regrowth so yeah, they did live for a bit.

Chris - I think, was it Imhotep, was someone who documented one of the first linkages between what the brain does and the movement of the body? But I remember reading a text where I think it says if you put your finger through the hole in someone’s head and stimulate the brain underneath and the person shudders. And it’s sort of linking the fact that the brain makes you move because people didn’t really know what the brain did historically.

Meghan - The Egyptians didn’t have very high regard for the brain. They discarded it when you were mummifying somebody…

Chris - Through your nose?

Meghan - Exactly. Yank that out.

Chris - Scoop it out?

Meghan - Yeah. You were dead when that happened so that’s good.

Chris - You certainly where whether…

Meghan - whether you wanted to be or not. By that point you were definitely dead. Imhotep, he was actually quite a high regarded physician/priest and is actually deified by the time you get to later periods because of his knowledge. So yes, he was quite a famous person for his day.

Chris - So working on the pyramids was quite a privilege then.

22:21 - EXCLUSIVE: What did Homo naledi's brain look like?

EXCLUSIVE: What did Homo naledi's brain look like?

with Lee Berger, Wits University

Chris Smith spoke to human origins expert Lee Berger from Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, about his recent Homo naledi discoveries at the Rising Star Cave. He even brought skulls, hands and feet with him...

Lee - One’s an old friend of course. One is the actual type specimen of Homo naledi from the Dinaledi chamber. This is the one that we announced almost three years ago, I guess. We didn’t know how old they were at the time but it was the most complete skull that we had.

Interestingly, if you’re looking at this skull to describe it, it’s a brown skull but the white part in the front is the nose area which we didn’t have. These are some of the most fragile bones in the body and they did not preserve in those early specimens that we were pulling out so we kind of guessed at it. The rest of it all fit together but we had to guess at what the central face would look like so we put a nose on there based on the way the face was angling down and also the advanced features we were seeing in some of the back parts of the skull.

I’m really pleased to say that we discovered a skull in another chamber, the Lesedi chamber, and we announced it about four months ago...

Chris - This is the same cave system, it’s another chamber off of where you discovered these specimens?

Lee - About 110 metres away. Again 40 metres deep; very inaccessible. We found a skeleton there that had a complete skull. This is the skull, I’m now holding that one now in front of us. I’m pleased to say, after all that work, we got the face wrong in the original reconstruction. It’s very clear when you see the second skull (Neo’s) nose, that it’s much flatter. When I hold them up together you can see the difference in the reconstructions.

Chris - You hedged your bets a bit when you guessed, because you gave him a much more prominent nose. More towards what we would regard as human-ish?

Lee - A "Homo erectus-y" kind of thing! And that was being led by some of the shape of the skull. It’s clear though that Homo naledi (Neo’s) skull, and face is much flatter. Much more primitive.

Chris - Just to describe this for people at home: the actual skull vault is a bit bigger than fist sized I’d say...

Lee - Yeah.

Chris - So this would have been quite a small-headed individual. When would these have been running around on Earth? When do these date from these specimens?

Lee - When I was on your show last, we said they must be millions of years old. Every scientist was trying to guess at how old Homo naledi was based on the anatomy of the heads, of the body. There were several papers published saying it was a million and a half, two million, maybe two and a half million years old.

We now know that this population of Homo naledi in the Dinaledi chamber is actually around two hundred and fifty thousand years old. Between about 180 thousand and about 340 thousand with the central point around two hundred and fifty thousand years. That is really young. It’s really kind of put a landmine in the middle of archaeology and palaeoanthropology because that sort of primitive ancient human relative should not have been alive at that point according to what we’d been finding.

Chris - Meghan was talking about the ancient Egyptians burying their dead. That’s the striking thing about these individuals isn't it? You found this in a cave system where really the only way that that they could have got those bodies into that cave system is that they took them there?

Lee - Our very controversial hypothesis that we put forward about three years ago was that the Dinaledi chamber was a deliberate body disposal site. They came down this amazingly narrow shoot entrance. It has enclosures 17½ centimetres wide, say 7½ inches wide, down 12 metres, which is 50 feet or so.

Chris - Because the job advert you put out for people to work on this project said, “I want small, skinny women!”

Lee - No, I didn’t say women. I said I wanted a skinny scientist!

Chris - It’s the only job advert you can actually say these days - legitimately - and say "I want skinny people," isn’t it?

Lee - That’s right! We did hypothesise that they were deliberately disposing of the dead. That’s not been disproved - it still sits as the most valid hypothesis. We now have, of course, not just one more chamber - the Lesedi chamber - we found another chamber. I just came out from underground about 4 weeks ago. Now if one thing when we talk about Egypt or other places and deliberate body disposal like that but not with this brain. It’s just very hard to fathom that they had that complexity, yet we’re faced with “it is what it is.”

Chris - They’re very small-brained aren’t they? If one looks at the inside of the skull you can some idea as to what bits of the brain might have been doing what and what the behaviour of an animal may have been because it tells you about the size of the underlying brain. So if you look at these specimens, what does the brain look like?

Lee - Well, in fact that paper’s just about to come out...

Chris - Oh damn!

Lee - No, it’s okay. I’ll go ahead and break it!

Chris - Exclusive for the Naked Scientists then!

Lee - I’ll give you the exclusive! it’s very complex. Our scientist who’s been studying our image of the brain that’s pounded out on the inside of the skull all his life said "it’s finally the brain I’ve been looking for my entire life, because it’s very advanced. It’s very complex but it’s tiny."

Chris - Did they have language? If you look, is there a swelling on the left hand side roughly where the language centre might be? Were they talking to each other?

Lee - There is. Broca’s area is enlarged; there’s bilaterally symmetry. We don’t know if they had language. I can tell you that if we are right about this sort of very complex behaviour, I would be very surprised if they did not have a language or a communication much more complex than any animal communication we know of.

Chris - So maybe not hieroglyphs, Meghan, but they could have been saying something!

27:41 - Did dinosaurs live in herds?

Did dinosaurs live in herds?

This question came from Jack on the Naked Scientists facebook page. Chris Smith put it to palaeo-zoologist Jason Head, from the University of Cambridge...

Chris - "Did dinosaurs live in herds, or on their own?" - So, were they lonesome dinosaurs, or sociable sauropods?"

Jason - We know this from a couple of different lines of evidence for different dinosaur groups. We have trackway evidence that shows that groups like Duck Billed dinosaurs and the large long necked Sauropods were moving in multiple age class groups.

So you would have adults based on the size of their footprints, and juveniles and babies based on the size of their footprints moving in the same direction, and also changing directions in the same pattern and the same orientation, which suggest the animals just weren’t going along the same direction, they were making the same turns, the same manoeuvers.

That suggests animals moving in the same direction and the same grouping. We also have a few big monospecific bone beds which are catastrophic events where you have a population of dinosaurs that is killed usually be something like a flooding event.

Very famously there’s a group of horned dinosaurs called Centrosaurus from Alberta and there’s a mass death assemblage of these animals. So hundreds and hundreds of individuals in a bone bed, in a single horizon of rock, which really looks like a large herd of animals that was killed in a flash flood event. There are modern Caribou mass death assemblages that are patterned just the same way that we see in these animals.

29:49 - QUIZ: To Early Earth and Beyond!

QUIZ: To Early Earth and Beyond!

with Lee Berger, Meghan Strong, Owen Weller, Jason Head

It's not a Q&A show without putting our experts through their paces with a Naked Scientists quiz. Team One was Human Origins expert, Lee Berger, and Geologist, Owen Weller. They were up against Team Two: Palaeontology, Jason Head, and Egyptologust, Meghan Strong. And so it began with Team One.

QUIZ Q1: Pirates wore eye patches so they could see in the dark!

Chris - Is that science fact or science fiction?

Lee - I’m going to go false. How about you Owen?

Owen - I think the eye patch was so that when they came out of the bottom deck they could adjust their eyes to the light easier.

Lee - You're going to say true?

Owen - I’m going to say true.

Lee - I’ve got to go… you know there are ballast in the rocks.

True - It sounds like a joke, but it’s widely claimed that they wore eye patches to cover missing eyes, but they more often did this so that they could keep one eye adjusted to low light so they could see when they went below deck...

QUIZ Q2: True or False? Ancient Greeks would get drunk after making an important decision. They would know whether it was sound if they still felt the same way about it when drunk.

Chris - Is that science fact or science fiction - what do you two think?

Jason - I kinda want that to be true.

Meghan - Yeah. I know that Greeks liked to drink.

Chris - What today, or historically?

Meghan - They have tons of stuff dealing with wine: wine stringers, wine drinking cups, one drunk in wine drinking scenes.

Jason - And so much is written about the importance of wine, and the philosophy behind wine, and so…

Meghan - I’m going to say true. Yeah, we’re going to go with true.

A: False. I liked your logic but it was the Ancient Persians - (550-330 BCE). According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, the ancient Persians had a ritual of intoxication. They believed that you could only tell the truth when you were drunk, so they would drink a lot of wine after deciding on something and if their minds still felt the decision was right when then it is considered the right decision!

Chris - I think you’d have to be drunk to come up with a rule like that wouldn’t you?

Chris: Time for Round Two on size. Over to Team One.

QUIZ Q3: What number is bigger? Tastebuds on a human tongue, or the number of stone blocks used to build the giant pyramid?

Lee - Tastebuds.

Owen - I would go with tastebuds.

Lee - We’re going to go with tastebuds just because there are not that bigger pyramids, and there’s a void in them.

Chris - So you’re going true or false?

Owen - We’re going tastebuds.

Chris - You're’ going the larger number are tastebuds?

False - The pyramid wins!

Did you know that Meghan?

Meghan - I would have gone with tastebuds.

Jason - Did you count the void - the new void they found?

The pyramid wins! We estimate more than 2 million stones were used to build the Great Pyramid. That number’s at least 100 times larger than the 10,000 or so tastebuds on a human tongue. So not that many tastebuds.

Currently you're still in the lead you two but let’s see, this other pair might equalise now.

Over to TEAM ONE.

QUIZ Q4: What’s larger, the distance from the surface of the Earth to the centre of the Earth, or the distance from the surface of the Earth to where the International Space Station is orbiting?

Jason - That’s going to be distance from surface to centre.

Meghan - Yeah.

Jason - Greater distance would be the surface to the centre.

Chris - Do you know how far it is?

Jason - I believe… isn’t the diameter 5… oh no.

I’ll get this wrong - 5000 plus kilometres I believe is the diameter isn’t it?

Chris - It’s not surprising Owen has his hand up.

Own - Can I get a bonus point for suggesting 6,371 kilometers plus or minus? It’s actually greater at the equator than to the north.

Chris - True. The Earth’s centre! It’s about 6000km to our planet’s core although there is a bulge around the equator to make it slightly larger between the surface of the core of the centre of the Earth, but only about 400km to the altitude at which the ISS orbits.

One all so far. So here we go onto the final round.

Chris: Now for the final round, firsts. Team One, over to you.

QUIZ Q5: What came first, Coca-Cola, or “Tyrannosaurus Rex”?

Lee - They’re going to refer to the name there I presume. So we’ve got Coca-Cola in late 19th century right - early 20th century? And Tyrannosaurs Rex is going to be later than that I guess on naming. What’s your thought’s Owen?

Owen - It has to be a trick question presumably.

Lee - No. We’re not allowed to think like that. I go with Coca-Cola anyway.

A: Coca-cola. They company was founded in 1892, the Tyrannosaurus Rex was given it’s name by Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, in 1905.

So that’s two to Lee and Owen. Meghan and Jason currently on one. Let’s see if you’re going for a tiebreaker.

QUIZ Q6: What came first? The discovery of the hole in the ozone layer, or the first space shuttle launch?

Meghan - I was going to say space shuttle.

Jason - We’ll go with shuttle.

A: Space Shuttle. Columbia blasted off for the first time in April 1981; the ozone hole was discovered in 1984 by 3 scientists at the British Antarctic Survey. Brian Gardner and his colleagues. That was in Cambridge when they made that. They didn’t make the discovery in Cambridge obviously, they went to Antarctica to make the discovery but they were working in Cambridge when they made that discovery. It lead to the Montreal Protocol in 1986, the banning of chlorofluorocarbons in fridges and aerosols and things. And the ozone hole which is currently Australia sized has stopped expanding so we think that, actually, it was one of the most important interventions on environmental grounds we’ve yet made.

It goes to a tie break. Whoever gets the closest answer, wins.

Chris -Final question, when did the last woolly mammoths walk on Earth? Answer to the closest I’ve got written down here. What do you all think?

Owen - About 18,000?

Lee - I’m going to say something very different than that.

Chris - Are you guys ready?

Meghan - Yes.

Jason - Yes.

Chris - Well let’s give Lee the chance first. What do you reckon?

Lee - I’d say about 3½ thousand years to 4 thousand recent ones found in.

Chris - So 3½ thousand years to 4 thousand years ago or BC?

Lee - Oh BC.

Chris - Okay. You're going to 3½ thousand years to 4 thousand years BC.

Let’s go to the other team, let’s go to Meghan and Jason, what do you think?

Jason - I thought it was about 4 thousand.

Meghan - Yeah. That sounds right.

Jason - We have effectively the same answer.

Chris - A: 1650 BC. Although, most of the woolly mammoth population died out by 10,000 years ago, a small population of 500-1000 woolly mammoths lived on until 1650 BC. For context, Egyptian pharaohs were midway through their empire and it was about 1000 years after the Giza pyramids were built.

So I think everyone gets a point so we have actually a perfect solution that no-one goes home any the wiser on any much a winner. So very well done to everyone there.

37:42 - How do you age a rock?

How do you age a rock?

Chris Smith put this question to Geologist, Owen Weller, who brought in a very old rock into the studio with him.

Owen - Not my favourite rock but it is the world’s oldest rock. This is dated at 4.03 billion years ago and, to put that age into context, as I said before, the Earth is 4.56 billion years ago, so it’s the oldest rock. To date this rock we need to do some form of radiometric dating. This uses the principle that some elements are unstable and they will decay to stable isotopes.

Chris - So radioactive decay?

Owen - Correct. With a known and constant decay rate. So if we can accurately measure the ratio of what they call parent and daughter isotopes in a given sample using a machine such as a mass spectrometer, then we can ascertain the age of the rock.

Chris - So just summarising then… you know that just by chance there are some radioactive atoms in that piece of rock, and we know that radioactive atoms like that break down at a certain rate, which is a constant rate, and they turn into new types of atom. If you count how many of each type are there you get some idea as to how old, or how much time has elapsed because we know how fast that process happens, on average.

Owen - Yes, that’s correct. There’s actually many different radioactive decay schemes, so many different pairs of elements that you might measure. But the most common one that we use is the decay of radioactive uranium to stable lead, and we most typically measure this in a very special mineral, which is called zircon. Maybe people don’t realise it but there’s zircon present in many rocks, particularly granites, around the world. It has several extremely useful properties. First of all it’s extremely durable so it can last for several billion years. And second of all its structure really likes to take in uranium but doesn’t like lead, so when we find lead in its structure we know that that’s come from the decay of uranium in the structure from when that zircon formed or it was crystallised. So by measuring the ratio of uranium to lead in our zircon, we can say when the zircon, hence the rock crystallised and that’s exactly what was done with this piece of rock that I brought in today to say that it was 4 billion years old.

Chris - Lee?

Lee - I just had a question to follow on because I was thinking the oldest rock on Earth. Are there any fallen objects that are older than that that are on Earth, like meteorites or moon rocks or whatever that are actually older than that that are on planet Earth now? Owen - You’ve caught me. I should have said the oldest terrestrial rock. You’re quite correct. We do have meteorites that do date back to Sun or the Earth so to 4.5/ 6 billion years old.

Chris - Where do they come from - space obviously but were they just rained in from the debris that formed the solar system in the first place at some point in Earth’s history?

Owen - Yes, absolutely. There’s a whole variety of different meteorites that we get and the very oldest ones, they’re a particular kind called chondrite or chondritic meteorites. They’ve been really, really useful for telling us how the Earth formed because we get some slightly younger types which are then either formed of iron or they’re formed of silica minerals. This tells us very on in the Earth’s history we formed the Earth’s iron core and the silica exterior, so meteorites have been extremely useful probing these very, very early Earth planet formation

41:13 - Why is there a void in the Great Pyramid?

Why is there a void in the Great Pyramid?

Chris Smith asked Egyptologist, Meghan Strong, to fill in the gaps with this question from Gilad in Oxford.

Meghan - I think it’s a bit early to say. This comes from an article that was published last week in Nature. A Japanese team went into the Great Pyramid, the pyramid of Khufu which dates to about 2450 BC. They used muon particles, speaking cosmic rays and other kind of cool elements, but they used these in order to scan the interior of the pyramid to get a very accurate sense of where all the chambers are etc. In the midst of doing that they discovered this previously unknown void which rests above another vaulted space that was purposely put there called the Grand Gallery, which is a ramped vaulted structure that lead us to the burial chamber of the king, and this void is above that.

As for what it’s for? I think it’s still a bit too early to tell. There are other, what are called, “relieving chambers,” so spaces that were purposely built into the pyramid to sort of take of the weight from these smaller internal structures. It may be something along those lines. It could be the remains of construction… who knows.

42:35 - Why did dinosaurs achieve so little?

Why did dinosaurs achieve so little?

Chris Smith asked palaeo-zoologist, Jason Head, from the University of Cambridge whether dinosaurs were under-achievers?

Jason - I love this question so much because it allows us to probe a few things about how we think about dinosaurs. Dinosaurs get their start around the same time as mammal groups do. Where we are today we have about 5500 living species of mammals and we’re pretty impressive in terms of the diversity of sizes and ecologies that we do today.

Dinosaurs today are somewhere between 10,000 and 18,000 living species, depending on how you measure species in modern birds. They evolved intelligence; they do amazing things; they fly better than any mammal. Then when you think about the mesozoic record of dinosaurs, they achieved giant sizes on land, they had an incredible diversity of behaviours, body sized, and ecologies.

So it’s important to not think of dinosaurs as just being big lumbering things that lived in the past. They are one of the most successful and diverse groups of vertebrates in our history.

Chris - You’ve got a lump of one in front of you. That looks incredible… what’s that?

Jason - This is actually not a dinosaur. This is better than a dinosaur. This is the cast of the vertebra of the giant snake Titanoboa. Titanoboa is a fossil snake related to modern boas and anacondas and this animal occurred about 6 million years after the end of the Cretaceous, so after the end of the non-bird dinosaurs, and it was about 15 metres total length.

Chris - So how long ago is that dating from in millions of years?

Jason - We’re looking at about 58 to 60 million years ago.

Chris - Okay. Can you just describe, so people at home can actually picture this in their minds?

Jason - Yeah. So this is basically kind of a squarish vertebrae with a ball and socket joint on it. It is about 5 to 6cm wide and about 4cm long.

Chris - It completely covers my hand if you put it across the palm of my hand. This backbone bone is completely covering my hand. So that would have been along the spine of the snake and the ribs would have opened up off of that and come round towards the front of the snake. What would have been the diameter of the snake’s body then where that was?

Jason - This is one of about 300 vertebrae, probably, that would have composed the spine of the animal, and then the ribs coming off would have given the snake a diameter of about half to three quarters of a metre.

Chris - Uuph!

Jason - And the total weight of the animal would have been somewhere between three quarters of a ton and a ton and a quarter.

Chris - Goodness! What would it have eaten?

Jason - That is a really interesting question. It occupied an ecosystem with giant freshwater turtles, giant primitive crocodile relatives, giant lungfish. And the answer is... whatever it wanted!

Chris - And it’s a constrictor so it would presumably have crept up on these things, grabbed them, and then inspiraled them, would it?

Jason - With a constriction force that no biological tissue could withstand. I cannot remember the number, but it is exponentially larger than the constriction force of boas and pythons today, and those animals are extremely powerful.

Chris - Lee?

Lee - I just love being a scientist because only scientists would use the understatement of every time we find a big fossil call it Titanoboa. It’s just fantastic.

Jason - Well, the original name my co-author, John Block, University of Florida, wanted to call it Tiranoboa, and I told him no. I do also want to point out - this is important - Lee’s Homo specimens, you can actually see the scans of them at morphosorus.org. The Titanoboa’s there as well. So if you’d actually like to see a 3D reconstruction of these vertebrae or download the datasets to print your own, that’s where you should go.

Chris - Why did that organism become so big? Why is that not here today - where’s it gone?

Jason - The hypothesis that we’re working on is that the reason you can get snakes that large is that during this time period, after the demise of the non-bird dinosaurs, and what we call the paleogene period of the cenozoic, this is one of the warmest intervals in the history of Earth. You have no ice at the poles; you have incredibly warm oceans; you have tropical rainforests that are extending up toward high latitude; you have crocodiles and palm trees at the poles. And with what we used to call “cold-blooded” or a “poikilothermic” animal, we know that body size is going to be ultimately limited by the temperature within which is lives. So what we’re able to do is actually do the math to calculate how hot it would have to be to keep an animal this size alive, and so we’re able to estimate temperature for this interval in time. They’re consistent with a lot of other data and so for our main hypothesis it is that these animals got this big because the climate allowed them to do so.

Did ancient human species fight?

This came in from the Naked Scientists Forum. Sounds like one for Human Origins expert, Lee Berger.

Lee - I love how questions like this always end with this sort of fight - the neanderthal fight club - kind of idea of human origins. We certainly know that species have interacted in the past - neanderthals are the best example, the best known. Not only did they interact; we don’t have any evidence of violent interaction, but we do have evidence of sex and the fact that many of us carry their DNA - a small part of neanderthal DNA. Usually somewhere in the 1½ to 3½ or 4% of DNA for Europeans or people from that area.

There are others that we know that we interacted with in similar ways - with denisovans, which are only known, in fact, from a fingerbone that’s now destroyed to get ancient DNA out it - we see some people on Earth sharing a small amount of DNA with them. There’s a sort of mystery species “X” that was in Africa about 200 to 300 thousand years ago that interbred with modern humans and we share some of that DNA. So we know that there were those type of exchanges that went on. What we didn’t know were that some species like homo naleti existed at the same time and place that modern humans did.

Now that’s going to be a tricky question right now because we have two lines of evidence in the record. We have fossil record which is very, very poor and very, very rare and we have an archaeological record which is rich and vast because it’s made of stone. And so we see this sort of technological spread and cultural spread across these regions, and we have always, particularly in Africa, assumed that in the last half a million years or so that that was all human - it was large-brained things. But suddenly, you have things like homo naledi popping up that are saying wow, wait a second it’s not that simple, things didn’t just go extinct. Humans and human relatives are a lot like other animals with existing lineages that went on longer. The hobbits on the island of Flores have shown us that and I think we’re going to see a whole lot more of that happening as we begin to open our minds and open up new areas and begin to explore more, there’s a lot more out there, a lot more mysteries to be solved.

Earliest mammal remains found in southern England

with Jason Head, University of Cambridge

A mystery was solved this week. There was a big announcement from the University of Portsmouth that a student doing an undergraduate project was looking at some rock samples from the south coast of England and found these tiny teeth which it was announced are the earliest evidence of mammals existing on the Earth and they date to about 147 million years ago. Chris Smith asked Cambridge University palaeontologist Jason Head to explain the findings...

Jason - They’re not the earliest mammals; there’s a little bit of confusion. What’s significant about these teeth is that they help us put down the divergence between placental mammals. So eutherian mammals which are the people in this room - your cat, your dog, most of the diversity of living mammals, and marsupials - the metatherians - so your pouch mammal, your possums, your kangaroos, your wallabies.

These are the oldest we think - unambiguous at the moment - record of placental mammals, so there are all sorts of mammals that are much older. What this is is a nice example of a pretty clear anatomical indicator that the divergence between marsupials from placental mammals that occurred basically by the beginning of the cretaceous period, around 147 million.

Chris - The mammals that were around at that time were obviously in competition with the dinosaurs. Is that what kept them small because these were small animals, we think, weren’t they - at least when these animals first evolved - probably because they were continually turning into lunch?

Jason - That’s a generally accepted idea that basically the diversification of dinosaurs would have inhibited the ability for mammals to radiate into new body sizes and new ecologies. And sure enough, after the end of the cretaceous, fairly soon after the demise of the non-bird dinosaurs you do see this big diversification - a flowering of modern mammals groups.

It takes mammals a little while to get much bigger. They don’t really achieve giant sizes until fairly late in their history. But yeah, for most of the mesozoic mammals, they’re very small, they’re probably nocturnal, they’re fairly ecologically limited. Although in the mammals defence there is dog sized mammal that we know from the early cretaceous of China called repenomamus which has dinosaur remains in it’s gut.

Chris - Oh, right. So they did get their own back to a certain extent. You mentioned something interesting there when you said they were probably nocturnal. Is that supposition of the fact that you’ve got something hungry with big teeth running around during the day that had very good eyesight - a dinosaur. So if you came out during the day you were more likely to turn into lunch, therefore, these early mammals probably came out at night and they could tolerate the cold better because they were warm blooded - is that where you’re coming from?

Jason - Actually, it has more to do with looking at behaviours in living mammals today. And one of the things that we can do is we can look at activity patterns across all of living mammalia, and we can actually reconstruct the ancestral activity pattern based on what we can see for all the living ones today. So if you look at four different groups of different mammals, and you look at their relationships and they’re all nocturnal, you can assume maybe their ancestors were nocturnal as well.

So when that’s been done for a huge number of species and mammals, what we actually find is that the most parsimonious solution is that mammals would have been primitively nocturnal. We also can see from the anatomy of their heads, their skulls, that these are small insectivorous animals with pretty decent sized eyes. And based on both of those and comparisons with modern insectivores today, the most likely interpretation is that they were nocturnal.

Chris - So we’re the unusual ones, coming out during the daytime - we’ve evolved to become day active when, actually, we’re bucking the trend? Most of our mammalian ancestors would have been night active.

Jason - Most of mammal history is being small, nocturnal, and afraid of reptiles. It is after the cretaceous again, it’s during this big flowering and big diversification of mammals in the early cenozoic that we definitely started to see really diurnal mammal ecology really develop.

What is a tectonic plate?

Chris asked Geologist, Owen Weller, to shake things up with this question from Clare on Twitter.

Owen - Well, that’s three questions in one so I’ll start with the first one. A tectonic plate forms part of the outer, relatively cold and rigid part of the Earth that we call the Lithosphere. Essentially, as you go into the Earth the Earth warms up quite quickly and the effect of increased temperature and rock strength is to decrease rock strength. The lithosphere is the relatively cool part where rocks are relatively strong and relatively rigid but as you enter the Earth they become much weaker and they can, in fact, flow on geological timescales, this is flowing in a solid state. So tectonic plates and the lithosphere is just the strong outer layer and below this sits what call the Asthenosphere. So the analogy is the tectonic plates are like icebergs which are flowing under the asthenospheric mantle below.

Chris - Vagner had the idea that this might be happening more than a hundred years ago, but it took quite a lot of data to emerge subsequently to prove that this was actually happening. What about the other part of that question which was “other planets.” Is the Earth unique in having this geological activity or do other planets appear to do the same thing?

Owen - That’s a great question because, in fact, it’s an ongoing area of research. Certainly other planets show evidence for geological activity. For instance, we can see on satellite images of Venus that we have enormous volcanoes and that we can date the surfaces of planets by how pockmarked they are. So we can see that some planets are being essentially resurfaced by volcanism. However, what we don’t see is the sort of geometric arrangement or jigsaw of tectonic plates that we observe on the Earth today.

However, one really exciting new area of research is on one of the moons of Jupiter called Europa. Researchers there are suggesting that we in fact have an earth-style plate tectonics where you have the creation and destruction of plates but these plates are, in fact, made of ice, so we call this icy tectonics. It’s a sort of ongoing area of research.

Chris - So the bottom line is you need what we have on the Earth - a squidgy interior with something fairly rigid on the outside and not too heavy to bob around on that squidgy interior and that moves things and jockeys things around and remodels the surface? So as long as you’ve got that sort of configuration it doesn’t really matter where it is or what it’s made of, the same processes will play out?

Owen - Absolutely. It is a little bit of a Goldilocks situation where you need the right thermal profile and you need the right chemical properties. So, for example, Venus has a very similar size and thermal structure to the Earth, but it’s thought that there’s not quite enough water in the deeper parts of Venus such that it cannot flow. It essentially too strong on geological timescales. Whereas on Earth, we have just enough water buried in the mantle which allows these rocks to flow in the solid state.

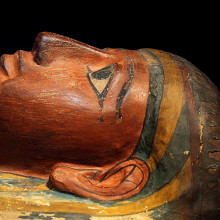

56:19 - What is the best preserved mummy?

What is the best preserved mummy?

Chris Smith asked Egyptologist, Meghan Strong, to wrap things up on this question from Caitlyn in Australia.

Meghan - The mummification process is a means of artificially preserving the body, and the reason for the being is that the ancient Egyptians felt that they needed to have their body preserved intact, in its entirety, in order to have an afterlife. For most people, that probably just involved being wrapped in a shroud or a reed mat to keep the elements off of you, or even just backfill from the grave that you were being put into.

However, if you were wealthy enough, or if you were well connected to the king, or something along those lines, you could have more of the ‘Rolls Royce’ treatment of mummification which was incredibly detailed and took up to 70 days. Most people understand that they removed the internal organs. They would have preserved those separately in their own jars. And then the whole body would have been put into a bathtub or a vat basically filled of natron salt, which is a salt that is native to Egypt. That would have completely dessicated the body so that you would have had this perfectly preserved human. Then that was anointed, wrapped in yards and yards of linen, and then you would have had your mummy.

The best preserved mummy is either Ramesses II, Ramesses the Great, or his father Seti I. And he was actually used as the stereotype for the mummy movies that Boris Karloff was in so I think he was pretty good.

Chris - So that’s your favourite - that gets your vote?

Meghan - Yeah. I think I like him best.

Related Content

- Previous Type 2 Diabetes Reversed in Rats

- Next Matchmaking at the zoo

Comments

Add a comment