Publishing & Politics: How Science Gets Made

What’s a scientific paper? What’s peer review? And when governments say they're "following the science" during this pandemic, what does that actually mean? We're figuring out how science goes from results in a lab to become public information, or even national policy. Plus, in the news: we rate the security of the UK’s new COVID-19 tracing app; doctors that didn’t know they’d been infected with coronavirus; and should we really be bailing out airlines?

In this episode

01:02 - The NHS coronavirus app, rated

The NHS coronavirus app, rated

Greig Paul, University of Strathclyde

The NHS’ mobile phone app designed to tackle COVID-19 - currently being tested on the Isle of Wight - will soon be rolled out nationwide. It’s job is to track down everyone an infected person has been in contact with, and it’s part of a wider approach to test, trace, and isolate infected individuals so they don’t spread the disease. This so-called “contact tracing” is an old idea that normally involves interviews and questionnaires; the app is for catching connections that the old methods would miss, such as strangers on a bus. But there have been questions surrounding how it treats the data of the people who use it. So Phil asked the opinion of security engineer Greig Paul...

Greig - When you're using the app, you don't need to do anything. In the background, though, your phone is seeing if any other devices appear over Bluetooth; and if there are devices running the app out there, they'll exchange a little handshake and they'll keep a record of that. Nothing will happen with that - it will stay on the phone, and in 21 days' time it'll disappear and be deleted off your phone. But if somebody later reports symptoms - they start to feel unwell - you can click a button and upload to the NHS a list of the people, the devices, that you were in contact with. The app allows the NHS to get an idea of whether this is likely to be a true claim of symptoms or a false claim of symptoms by someone, just having a laugh and clicking the button for example, based on if they've been exposed. But then they can actually alert the people that they've been in contact with. And that could allow you to get people and say to them, "look, you might be exposed, you should self isolate," and then in two or three days' time they might experience symptoms.

Phil - Don't you need everyone to have the app, though?

Greig - You don't need everyone to have the app. Research suggests that if you get about 60% of the population, you'll start to get some gain. You're never going to get everyone to install it; but that's okay, because you're still going to have regular procedures of contact tracing. People will be following distancing measures, they'll be washing their hands; but the idea is to augment that process.

Phil - How does this compare to apps that other countries are trying? Like this COVIDSafe app that Australia has been using?

Greig - So there's two general approaches that are being taken to how these apps are being developed at the moment. There's the centralised and the decentralised model. Australia's COVIDSafe app is using the UK approach, the centralised model.

Phil - What's the difference between that and decentralised?

Greig - Some countries are looking at building decentralised apps - a lot of European countries are interested. These work almost in the reverse manner of how the UK's approach is. The UK focuses on someone who's infected, sending a list of people they were near, to a central server run by the NHS. In the decentralised model, everybody keeps a list of the devices that they see; and if someone gets infected, what everyone else has to do is look through their record of what devices they've been around, and see if any of the infected ones are devices that they've been close to. In both cases, you don't send anything to the health service server unless you've been infected.

Phil - Can I make a comparison to see if I understand it?

Greig - Sure.

Phil - Is it like you've got to give the police an alibi for something? The centralised version is you saying, "well I saw this person, this person, this person, and they can all verify that I'm fine." Whereas the decentralised version is going, "okay, well I was wearing a green hat and a red jumper, and so people would have seen that, so you can ask people if they saw someone with a green hat and a red jumper."

Greig - That's a pretty good analogy. In the decentralised model, you have to tell everybody what happened. Whereas in the centralised one, you tell the NHS what happened and they can go and alert people as needed.

Phil - To someone who's not a software guy that seems like quite a small distinction...

Greig - It seems a small distinction, but from the privacy perspective, the distinction here is quite important. A lot of people feel the privacy of the decentralised system is better. I think what they're often overlooking is that even in the decentralised system, they are actually revealing this information; and if you create a list of people who have been infected, there's a lot of privacy concerns around that, especially when that list is being circulated to everybody as a virtue of the design. With the NHS system, you don't do that. What you do is you privately notify the NHS and the NHS notify someone. There's no big list that anyone could look at to see who's been infected. Any country that's looking to build the decentralised model will end up having such a list; a lot of countries are looking at the Apple and Google approach, and it's the approach they are firmly pushing to everyone.

Phil - But it seems like people are worried rather than about everyone having their information, maybe a big company having the list of where you've been and who you've been in contact with.

Greig - Sure. So the first thing that's important to know is with both of these approaches, there's no list of where people have been. There's no location data being gathered. There's no location data being stored. There's no location data being sent anywhere. Now with regard to who people have been in contact with, we're not talking about names and addresses. We're not talking about phone numbers. What we're talking about is random numbers that are linked to that person, that there isn't actually... it's not possible to go and look at who that is and determine anything based on that.

Phil - Greig, are you going to get the app?

Greig - Yep. Already downloaded it.

Phil - You've already downloaded it!

Greig - Yes. So for the purpose of the research, I've already downloaded it.

Phil - How do you find it?

Greig - It's very simple and straightforward. There's not really much to it, to be quite honest.

Phil - If you had to give it a Greig Paul privacy rating out of 10, what would it be?

Greig - I think for this app would probably be looking somewhere around an 8 out of 10.

08:47 - Hospital staff infected without realising

Hospital staff infected without realising

Steve Baker & Mike Weekes, Cambridge University

Hospitals could easily end up being hotspots for coronavirus spread. That was the thinking behind a study into how many staff at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge have been infected. Worryingly, quite a few had been continuing to work not they’d had the coronavirus. Chris Smith heard the results from their source - Cambridge University microbiologist Steve Baker and Infectious Diseases consultant Mike Weekes...

Mike - It's obviously a huge issue because staff within the hospital could transmit the infection to other staff and to patients, and actually hospitals could become their own individual hubs of transmission unless we do something about it. Staff wear PPE throughout the wards, but obviously people don't wear PPE in staff rooms; they don't wear PPE when they go to lunch, because you can't; and so there's the possibility that the virus could transmit. We got our infectious diseases team to visit different wards around the hospital, and take swabs from people's throats and noses, so that they could go to Steve's lab and we could see if they actually had coronavirus.

Chris - You got these samples from all over the hospital. How many samples did you get, Steve?

Steve - At the moment I think we've screened about two and a half to three thousand individuals in the hospital.

Chris - How long does this take?

Steve - The whole process from the point that we can receive the swabs, to we can report back - the quickest we've done it is about four hours. Usually we report back a result within 24 hours.

Chris - And Mike, you've looked at these staff members. What did you find?

Mike - It's really interesting. We actually found that three in a hundred people tested positive for coronavirus, and actually these people were split into three groups. The first is people who have no symptoms at all, and so they just have no idea they have the coronavirus. The second is a group of people who've had mild symptoms, like a bit of a cough, a sore throat, some have even lost their sense of smell; and they don't think that they have enough symptoms to warrant doing anything about, in general. The final group we found, actually, had had coronavirus a long time ago; and they'd had fever and a prolonged cough, the typical symptoms, and they appropriately self isolated at home and then came back to work when they were well. You can still test positive even though you shouldn't be infectious.

Chris - The fact that these people are not reporting symptoms is worrying though, isn't it? Because we're relying on symptoms to detect who we think might have it in society.

Mike - You're quite right. Unfortunately this is one of the features of coronavirus, that some people just have no symptoms; and some people's symptoms are so minor, they just don't think they should do anything about it. But we're really encouraging staff now to come and see us, so they can get tested if they have any symptoms.

Chris - Hospitals are seeking to control this by dividing the hospital up into areas that are red, they have patients in them with coronavirus as a diagnosis, confirmed; there are also areas of the hospital which are regarded as green, those people don't have coronavirus. If you look at the staff who work in those different areas, are there any differences in the likelihood that they've got coronavirus infection, because they're being exposed more in red areas? Do they catch it more?

Mike - We did actually find a significant difference between red and green areas. In red areas a greater proportion of staff actually do have coronavirus overall, but it might be because staff are getting it from patients. It might be staff getting it from staff, or it might even be that we'd sampled more of the red areas a bit earlier. We sampled over the course of three weeks, but as everyone had been on lockdown, there were fewer and fewer cases in the community. We can't make any firm conclusions from this, but what we can definitely say is that this needs to be studied a lot more.

Chris - What if you're asked by the hospital, "right? What do we do with these findings? What are your advice points?"

Mike - Test, test, test, and then test again. Because the kind of approaches we can apply in the community, like these contact tracing apps on iPhones, won't necessarily work in hospitals because so many people have contact with other people.

13:51 - Airline bailouts with green conditions

Airline bailouts with green conditions

Richard Black, Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit; Brian O'Callaghan, Oxford University

Among the many economic casualties of this pandemic have been the airlines. The UK summer is about to start, but Heathrow airport is reportedly operating at one twentieth capacity, with a similar picture across the world. Many operators are asking the government for a bailout to help them weather the economic storm. Should we really be handing out public money to an industry that’s one of the major causes of climate change? Eva Higginbotham spoke to Richard Black, director of a think tank called the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit...

Richard - It seems that the lockdown on the airline industry is going to carry on for months, and the impact will probably be felt for years, to be honest. Obviously for those airlines, they have a choice. They either close or shut down some of their operations, or they seek some kind of economic relief, bailout, call it what you will; and that's what most of them are already doing. Within Europe, airlines collectively have asked for well over 10 billion pounds, and one can expect those amounts to carry on going up, I think.

Eva - Isn't that kind of propping up an industry that we know has negative consequences, considering the emissions that we have from air travel and climate change?

Richard - Yes. I mean if you look across all sources of carbon emissions, aviation emissions are rising among the fastest of anything we do, basically. And ways to solve this through technology aren't immediately obvious in aviation. It's really difficult to see how those emissions can be brought down anywhere near to zero in the 30 years that scientists tell us it would be wise to bring emissions down to zero.

Eva - Does it seem likely that the airlines are going to be bailed out by the government?

Richard - Yes. I think it's inevitable that airlines will be bailed out. So then the question is really, will governments put any conditions on those bailouts? Air France, the national French carrier - they're going to have to halve their emissions from travel within France by 2024, in just four years. Now that can't be done by technology, so it does mean that Air France will actually be reducing the number of flights it makes within France. Of course France has a very good train network, and so there's talk for example, "well, any journey that could be done in two and a half hours, you just won't be able to fly that route Air France. Sorry." That's the sharpest example yet we have of a government that is putting environmental conditions on that airline bailout.

Eva - What other bailout conditions could governments set? I put this question to Brian O'Callaghan, a researcher from the University of Oxford' Smith School for Enterprise and the Environment.

Brian - Those green conditions could include reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050; they could include intermediate targets like reaching 30% sustainable fuels by 2035; or a whole host of other green-type conditions.

Eva - Governments can set environmentally friendly conditional bailouts, but how do we make sure that the airline will actually follow through with the commitment?

Brian - The way you do that is by creating a negative result for failure to abide by the conditions. For example, if you're unable to meet a five year partial target, the government is able to say, "in exchange for the money that we gave you, we are taking half of your company and giving that half of the company to taxpayers." What that would mean is that existing shareholders and executives suddenly have their current shareholdings cut in half. That creates significant financial incentive for them to stick to the conditions which the government stipulate.

Eva - A classic example of carrot and stick then. "We'll give you some money now so your company doesn't go bust, but if you break your green promises, we're going to take ownership of some of your company." Now back to Richard Black.

Richard - Climate change is still going to be a problem once we've come out of the end of coronavirus. Why would you put loads of what's essentially public money, our money as taxpayers, into industries that are going to carry on emitting carbon dioxide and which will therefore create serious problems in the future with climate change. I think there are two ways of philosophically looking at bailout. One is that you'd simply try to go back to business as usual. The other is that you actually anticipate the future and you look at where economic trends are going, and you try and build industries that will have strong survival, they'll be sustainable in the future. Because then you're helping where the market is going anyway, and you're building industries that will be sustainable in the future. So I think there are two rationales for doing this. One is purely economic and looking to the industries of the future. And the other is that if you can basically meet your climate change goals at the same time as rebuilding the economy, why wouldn't you do that?

18:60 - How video calls affect your brain

How video calls affect your brain

Antonia Hamilton, University College London

Our conversations have gone virtual like never before: children are attending virtual school; many of us are working from home attending relentless video meetings; and almost everyone is using video calls to keep in touch with friends and family. What do we know about how a virtual chat compares with a face to face one? Katie Haylor spoke to social neuroscientist Antonia Hamilton from University College London...

Antonia - If you're on a live video call one-to-one, it's pretty similar to a real face to face conversation, how your eye movements, physiological responses behave; but then there's other aspects where it's much, much harder being on a video call. If I'm looking at an object or a piece of paper in front of me, to then share that with the person on the other screen is much trickier and I've got to start sort of thinking about camera angles and turning things around. Having video calls with multiple people is much harder, because you don't know who's going to speak next and you're losing track of who's where.

Katie - And does the quality of the communication differ?

Antonia - It probably does, but it's hard to pin down the exact ways in which it does. And I think it depends on the kind of conversation you're trying to have. "When's our next meeting" and "what's happening on this particular event" or something - that's probably going to be just as effective in either context. Whereas if it's a difficult conversation, it's a highly personal conversation, it's probably going to have a much bigger impact on the quality.

Katie - When we last spoke you mentioned you were just about to start a study on virtual conversations...

Antonia - We create a virtual person who'll have a conversation with you. We can have two different virtual people. One of them nods in the way that we think is natural; and then another virtual person, they just do some sort of head movement behaviour that isn't related to conversation. They're pretty preliminary results, but certainly our data suggests that you like the character more if that character shows natural head movement behaviour - they're nodding in time with you, they're nodding in response to the things that you're saying.

Katie - I've just noticed I've been nodding along to you despite the fact that we've turned the webcam off, so you can't see that I'm nodding along! But there we go.

Antonia - Yes! I was talking to somebody - I'm not sure if it was you - but somebody in radio who said that radio people do a lot of nodding when they're doing an interview behind glass and they want the other person to keep talking.

Katie - I definitely find virtual communication more taxing than face to face. Why is it so tiring?

Antonia - You're not getting these cues automatically, and so you're having to make a bit more effort to remember that there's another person there, that they can see you. Often you're seeing yourself on the camera, which is really distracting, and so you're sort of having to work a bit harder with all of these aspects of engagement.

Katie - Can I ask you about differences in social behaviour? Because I think some people, they move quite a bit more in conversations; and indeed some people find it quite difficult to communicate socially. Do you think that has implications for the pretty intense time we're in now?

Antonia - I think it probably does. There isn't new data yet on how people are coping with everything, having to switch to virtual conversations. I know of a group working with children with autism, interacting with them over webcam interfaces, and some of the autistic children seem to engage quite well with that because they have less anxiety when there isn't a physical person in the room, but they'll still engage with the person at the other end of the camera. But other people find that they really want much more physical social interaction; they're not getting that from the webcam. A Skype conversation doesn't leave you at the end with that same feeling of friendship maybe that you would have from actually having a pint in a pub with a real friend.

Katie - Do you have any communication tips during this time when virtual communication is just so much more frequent?

Antonia - I guess the main thing is to have a bit more patience with other people with the technology. Certainly if it's a group call, it's very worthwhile establishing rules at the beginning of 'this is how we're going to organise things'. Some of these bits of software have things where you can click a button to send a clap, or a heart, or a smile, or a thumbs up, or something like that. And we can see, in the context of things like texts and messages, how emojis have now become this enormous world of different things, because people want ways to communicate without having to put everything in words. We encourage people to use the option to chat, the option to put some emojis, because all of these types of backchanneling are really, really useful in conversations. And that's again one of the things that we often lose when we go virtual. So we can do it, but it does take more effort, it takes more patience, and it's important to take breaks and get away from the laptop as well sometimes.

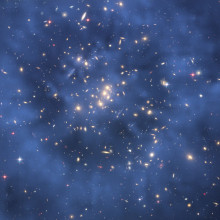

24:15 - Science from home: dark matter physics

Science from home: dark matter physics

Ben McAllister, University of Western Australia

How have scientists been adapting to life without their labs? We’re exploring some of their weird and wonderful lockdown setups on the show - and this week, here’s how one physicist has been scratching his scientific itch...

Ben - Hi. My name's Ben McAllister. I’m an experimental physicist, and like many of you I’m currently working from home.

What does an experimental physicist do at home, you might ask? Well, so far I’ve investigated the gravitational and mechanical properties of my cat...

I’ve constructed a helpful robot from scrap materials and household rubbish...

And like many of you, I’ve been conducting thorough experiments in fluid mechanics.

I want to make it clear to my funding bodies that that was all a joke.

In all seriousness, I can actually get quite a bit of my real research done from home. My work primarily focuses on the detection of dark matter, which is this invisible stuff that makes up five sixths of all the matter in the universe, and which we have almost no idea what it is.

Fortunately for me and my ability to work from home, one of the things we do know about dark matter is that it is all around us, passing through the Earth, and through your very body right now as you hear this. We just can’t see, touch, or feel it. So I’ve captured a little jar of dark matter here, scooped it up in my kitchen, and I’ve been studying its properties from my living room.

Ok, believe it or not, I can’t actually do that part at home. All of our fancy machines and equipment which we use to try and detect the dark matter are down in the lab on the other side of town. But, thanks to the magic of the internet, I can control and operate a lot of those machines remotely and continue working on detecting that pesky invisible stuff.

Myself or a colleague does have to go in the lab from time to time to do a little bit of maintenance, or swap out a component so that we can continue to operate the machines remotely; but we minimise the number of people in there, and it’s a big lab, so we can easily maintain a safe social distance.

And of course, I can do a lot of the other jobs I have to do like data analysis, experimental simulations, and writing up experiments from the comfort of my armchair, without bothering the cat any further.

Oh god, the robot's back!

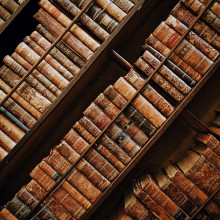

27:46 - Papers, please: the history of publishing

Papers, please: the history of publishing

Melinda Baldwin, American Institute of Physics

In almost all Naked Scientists shows, there will be words like paper, journal, and “peer reviewed” tossed around. These concepts make up the process by which almost all science is published for the world to see. However, journals and papers are relatively recent in human history, and have changed greatly over the past centuries. Melinda Baldwin is a historian at the American Institute of Physics who researches these changes, and explained them to Phil Sansom...

Melinda - So a scientific journal is a publication that publishes articles revealing new research results. There are a lot of different kinds of scientific journals: so for example Nature, which is one of the most prestigious journals in the world today, tends to publish short articles from every discipline; but many scientific journals today publish much longer articles and publish in a very narrow discipline.

Phil - Is this how science has always been published?

Melinda - It's not. For much of the early history of scientific publishing, scientific results could be published in a lot of different types of formats. So for example, Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species - that's a book. You also see men of science publishing their findings in pamphlets, in encyclopedias, occasionally in newspaper articles.

Phil - Why did journals then become the thing?

Melinda - During the 19th century, science as a whole became a much more stable career path. In the early 19th century, oftentimes - especially in the English speaking world - people who wanted to pursue scientific research had to do it as their after-hours hobby. Either that or they had to be independently wealthy so they would have enough money to support themselves. But during the 19th century, science becomes a much more stable and respectable career path. And what that means for publishing is that scientists no longer have to worry about selling their scientific findings to an audience outside of other scientists. And so the journal is a place where you're writing by and for other scientific researchers.

Phil - Science articles today, they obviously vary, but generally they're really hard to read...

Melinda - Yes, absolutely. If you go back to an early issue of Nature - one published in, let's say, 1870 - just about anyone could have read most of the articles. By 1900 it's completely different. And then by the 20th century you have articles that are so detailed and so specialised that not only can you not understand this biology article if you're not a scientist, you can't understand this biology article if you're not a biologist.

Phil - People describe articles as "peer reviewed" - is that people who do know about that article saying, "yes, that's okay"?

Melinda - Yes, exactly. When we say something has been peer reviewed, the article has been looked at by a number of specialists, usually one to four, and that those peer reviewers have said, "yes, this article should be published".

Phil - What was there before this?

Melinda - Refereeing was the term that was usually used. Starting in the 1830s at the Royal Society of London, the Society started soliciting formal reports about papers that were submitted to them for publication. The idea originally was that those reports were going to be published to spark scientific debates and discussions. That doesn't really take hold, but that comes in handy when you have someone who's a member of the Royal Society, but maybe written something that is a little wacky. And so by having these referee reports to fall back on, the editor can say, "oh, I'm terribly sorry. The referees said the piece is not acceptable."

Phil - Covering their butts.

Melinda - Yes, exactly. After that, a lot of learned society journals tend to use external refereeing to evaluate their submissions. Commercial journals, for profit journals, generally don't; and they don't do that well until the 20th century. It's not until the late Cold War that the scientific community starts to feel that something has to be peer reviewed in order to be considered scientifically legitimate.

Phil - Given that this is sort of now the way that people agree, "yeah, that's legitimate science," do you think that if you showed that process to someone from the 19th century it would be totally unrecognisable?

Melinda - I think it would be unrecognisable, and I think that if we showed the way we do things today to someone from the 1830s or the 1850s, they would probably see some problems. They would say, "what if the paper gets sent to a competitor who wants to sabotage? What if the paper gets sent to someone who's not really an expert in your field?" The fascinating thing to me about looking at the history of peer review is how much it changes over time. And it's something that can change again in the future.

32:37 - A crisis of reproducibility

A crisis of reproducibility

Brian Uzzi, Northwestern University

Today, high-ranking scientists are expected to volunteer their time to review work in their field before a journal will publish it. This reviewing is the foundation of trust that science today is built on. But how sturdy is that foundation? Are there parts that should be done differently? Brian Uzzi is here from Northwestern University, he researches the sociology of science, and he discussed the subject with Chris Smith...

Brian - The process of peer review works very well in some ways, but there's definitely room for improvement. So peer review basically tries to do two things. One, it wants to make sure that the findings are presented and the study was done correctly. Were the right statistics used? Were the right inferences drawn? Etc. And then the other thing that peer review tries to do is to make sure that the result is reproducible, that it can be replicated; do that's something that is published today, will work for the public tomorrow, for a week from now, for a month from now, even over an entire lifetime.

Chris - And how reproducible is the science then? If the whole process is working really well, we should have really, really reproducible papers. Are they?

Brian - Well, the issue here is that we're beginning to see that scientific papers reproduce at a rate lower than expected. In psychology, economics, and some parts of medicine and biology, we're learning that about 60% of the papers do not replicate.

Chris - Goodness me! So 60% of the science, if I take a paper off the shelf and I copy what the scientist who wrote the paper did, and I try to repeat their work, I get a different answer. Is that what you're saying?

Brian - That's precisely what I'm saying. So you use exactly the same procedures, you do exactly the same experiment, but maybe you only change the subjects in the experiment - and you find out that the first result was a fluke, not a fact.

Chris - But that sounds like a disaster!

Brian - Well, this is one of the reasons why people are beginning to look at this problem in much more detail; trying to find ways in which to improve the process of science so that more papers will replicate, and trying to find ways to predict whether a paper will replicate or not before it gets into the public domain.

Chris - But do we know why this is happening Brian? Has anyone unpicked the process that's leading to a paper just not working? Is it deceit on the part of scientists? Are they just publishing fraudulent science, or is something else going on?

Brian - Good question. The first thing that people looked at was, is this being driven by deceit? And there's very little evidence that it is. It appears that these are honest mistakes that are occurring in the research process itself. Now what you have to remember is: some papers will not replicate, you can't expect a hundred percent replication. Science is an innovative field; you're going to have experiments that end up on the cutting room floor, so to speak. But 60% is too high. And currently people are trying to bring that level down by understanding better the research process itself, and training people to learn how to make sure that their research replicates before they submit it for peer review.

Chris - Who are the worst culprits?

Brian - Currently, we can't give an answer to that because we haven't really begun to look at replication in all branches of science. Science is an amazingly diverse area of study, everything from the very hard sciences where you might look at, like, power station reliability; all the way over to mental health. What we do know is that the areas that we have looked at so far do vary in their levels of replication. So psychology and economics, medicine, some areas of biology - up to 60% of the papers appear to be failing. In other areas like engineering it appears to be lower.

Chris - How are you actually studying this? And I have to put it to you, is your research reproducible?

Brian - I could answer one of those questions! No, just joking. One way to do this is to improve procedures that scientists would use to make sure that their papers will replicate. Another way to do it is to develop procedures that allow someone who is reviewing someone else's paper to know whether the paper will replicate or not. My approach to that has been to develop an artificial intelligence system that reads papers, finds cues in the papers that human beings otherwise miss when they're reviewing the paper, but the AI system can tell us correlate with an accurate prediction about whether the paper will or will not replicate.

Chris - And does it work?

Brian - It works approximately 80% of the time. But the important thing is that for the papers that it feels most sure about - because the artificial intelligence system gives you a level of confidence in its prediction - for the top 10% of its most confident papers, it's right a hundred percent of the time. So that gives you real security in knowing that if you were to go to these papers and use them for whatever - investment purposes, what to build on in future research - you can be fairly convincingly secure that you're building on a fact, not a fluke in the paper.

38:33 - Preprints: straight from lab to web

Preprints: straight from lab to web

Theo Bloom, medRxiv

There's been an incredible boom in science related to the coronavirus, with more than 10,000 peer reviewed articles on the subject since February. Teams are rushing to publish as quickly as possible. And the quickest way to do so is not via a peer-reviewed journal, but rather through what’s called a ‘preprint server’; these are online platforms that have been the subject of global scientific attention and frantic collaboration. Theo Bloom is one of the founders of these preprint servers, called medRxiv - she’s also executive editor of the British Medical Journal - and Chris Smith and Phil Sansom asked her how it works...

Theo - Yes, we heard that scientists write up their results into papers to share with one another, because science is a collective enterprise and we all build on what everyone else has done before. But typically the process of peer review and preparing things for publication in a journal can take several weeks, up to months. And in this pandemic, we all want to know things much sooner than that. Now some scientists have always shared material with a few colleagues at the same time as they send it to a journal. But with the internet, we have the ability to share with absolutely everyone. And so preprint servers are a place to post that draft article that you've got ready for a journal, but put it out to the rest of the world too where it can have an awful lot of people looking at it, commenting, and saying whether they think the study's been well done and so on.

Phil - Presumably that's been something that's used quite widely in this pandemic to study the coronavirus - what's been happening?

Theo - Yeah, so preprint servers have existed in the physical sciences for tens of years, and they're only much more recently in the life sciences, in the last few years they've been growing in importance. And medRxiv, the clinical preprint server that I work with, only launched last June. We wanted to be very careful about preprints which could affect how people take their medications, cause public health panics if we weren't careful, and so on. So we happened to launch just a little while before the pandemic came along. But really from the moments in December/January when Chinese researchers were starting to see unusual cases of pneumonia, and worked out that they came from a previously unknown virus, they have been sharing their results; and now the rest of the world too, as rapidly as they can, and that has meant in preprint form.

Phil - What kind of scale are we talking about? How many preprints are you getting? How much in a day, for example?

Theo - We've currently posted around two or three thousand preprints on medRxiv, and we're seeing submissions of 70/80 a day at the moment. You know... "what's the best mode of treatment? What's the best models for how the disease is progressing? What has worked in countries that have seen reduced rates?" And so on.

Chris - Theo, do you get oversight of what goes on to medRxiv? So if I wrote a paper and it was complete bunkum, could I just put it there and you would put it out; or would you actually have some kind of ability to pull things that were quite clearly misleading?

Theo - There's two answers to that. One is that things are screened before they go up. This is not as rigourous as the peer review we've heard about, it's not about 'is it right' and 'is it replicable'. It's simply 'is this ethical, reasonable, and unlikely to cause harm to individuals or the population'. But even so that's a multistage process that takes a handful of days before things are posted; and on very rare occasions where something gets hugely criticised after it is posted, it can be taken down. But of course we know with, you know, in the internet in general it's very hard to remove something; so we'd rather it was right before we post it, rather than having to try and remove it afterwards.

Chris - It's interesting you raise the point about the fact there is discussion and critique, because that's kind of a strength of this, in the sense that researchers can almost have a preliminary run at seeing how - it's almost like a testing the waters - how their paper's likely to be received, and they can perhaps take some of that feedback and respond to it. Some people are saying they're concerned though when they put things into these preprint servers that someone might come along and steal their ideas, and then gazzump them scientifically speaking and publish the real deal before they do, by just replicating the work themselves.

Theo - I mean there certainly is that fear, but one of the things about posting it publicly with a date stamp is that the world can see that you did it first. And I think journals are increasingly recognising that that's an important feature. Scientists were realising this even before the pandemic, when they rely on things like showing what work they're doing to get jobs and promotions and grants from the funding bodies who fund their research; that being able to say, "look, I've done this work and completed it in January of this year", even if they haven't yet got a fully peer reviewed journal article out. So in fact in some ways it does give them protection from being scooped by someone else.

Chris - We've included in this programme in the past a number of items of things which have come from medRxiv and other preprint servers. We have been at pains to emphasize that this is non-peer reviewed yet. The thing is: is there not a danger that you will end up with things passing straight through and ending up in print, in press, in podcasts, in television, radio programs; and therefore disseminating the wrong message, if it's subsequently found that they are flawed and there hasn't been that normal editorial process that would have stopped that, the peer review process? So there's a danger of misinformation proliferating off the back of these preprints?

Theo - That's clearly a risk. And what I would say is twofold to that. One is, there's an awful lot of things published in journals that turn out to be wrong. And for that reason, if no other, most journalists and others will look for more than one claim of something before deciding that it's right. It's one of those things we're seeing a number of different reports from different locations, for example, saying that people lose their sense of taste and smell when they have a coronavirus infection. That started to come out as little reports of a few people in Italy and a few other people in China, and gradually it becomes, "actually, we're seeing that everywhere and it's something that can be added to trackers of symptoms," for example. So I would say it's always the case that a single result should probably not be relied on, but it's also an obligation to those who are desperate to share knowledge, to try and temper what they're saying with "how much can we rely on this particular finding".

45:39 - Are politicians really guided by science?

Are politicians really guided by science?

Jana Bacevic, University of Cambridge

It’s all very well publishing science for the general public, or other scientists - but how does that information reach governments and political leaders? Here in the UK, as in other countries, that process is a little mysterious - involving advisory groups such as SAGE, the ‘Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies’. SAGE is chaird by Chief Scientific Adviser to the government Sir Patrick Vallance...

Patrick - What we don't give advice on is precise policy decisions. Those are decisions which ministers must take. What we try to do is to come down to what we think is two or three options. I doubt we've ever gone and given a single option, we're more likely to have said, "here are the range of things".

Cambridge University sociologist Jana Bacevic explained to Chris Smith and Phil Sansom what this means...

Jana - What Patrick is saying happens there is that scientific advisory groups do not come up with policies, so they do not decide what the government is going to do. They provide the government with the necessary scientific basis, so with the evidence, that can help guide their decisions about what is going to happen; but they do not make those decisions themselves, of course.

Chris - That does mean of course you're then shifting the decision making onto people who aren't necessarily scientists. So is that not necessarily or potentially a flaw in the process? If I say, "well I'll give you five options, here's what you can choose from," how do we know that the politicians then are actually going to make the right choice?

Jana - Well, I think that's in a manner of speaking the mother of all questions. On the one hand, under a democratic system where the government is accountable to the public, this is obviously a good thing precisely because politicians are elected. So in that sense, the public can hold them to scrutiny. Scientists are in fact not elected to make decisions, so it is good that they shift decision making onto politicians. Of course, under conditions of emergency and especially public health emergencies, this process becomes both quicker and often less transparent than the usual. So in that sense, what the government aims to do often is to claim that science is guiding these decisions, often in part in order to argue that they themselves are not taking these decisions.

Chris - I'm glad you brought that up because that's been very visible here, isn't it? We're being told the government follow the science, they're having daily press conferences where they actually wheel out their most senior scientists, and they're saying these people will answer questions from members of the public. So in some respects that does appear to be transparent and good, but where they're being criticised is that when they then do make the decisions, we're not being told how they're making those decisions.

Jana - Exactly. That is one of the things that have been brought up as obvious faults of this process. I think the other element is, the government has not been quite transparent about how they have come to adopt specific kinds of scientific advice. Because as the chief scientific adviser has said, normally scientific advisory groups tend to inform the government in terms of what would be the outcomes of certain measures; but then what is the government being led by when they decide which measures to adopt is not entirely clear.

Phil - Do you think that in general they might have already made up their mind, and will then pick whichever one best justifies that decision?

Jana - I think again, under conditions of emergency, the politicians are more likely to already have an idea concerning what is it that they might want to do. And they're driven by a number of factors. Some of these factors concern the economy; some of these factors concern estimates about what is likely to win popular approval or support; they're often guided by foreign policy concerns; and so on and so forth. So even if they do not have a clear idea of what is it they might want to do, they almost always have a clearer idea about what things are entirely off the table or out of the question. So in that sense they are guided by their own policy preferences, certainly.

Phil - What about this idea that there's this difficulty in communicating when you try and translate between a scientist and a policymaker. Is that something that might be making the science go a bit astray?

Jana - Absolutely. I think one of the things that tend to happen in science-policy communication is that scientists tend to be very cautious about giving advice. And that is in part, of course, because the reality is complex, and because it is usually very difficult for them to predict things with a high degree of certainty. Politicians on the other hand tend to value and privilege advice that seems to give clear indicators of what outcomes of specific policy decisions are going to be. So in that sense, scientists always err on the side of caution, and politicians prefer to have clear data and clear advice that would also give them sufficient grounds for policymaking. But on the other hand, that will also give them sufficient reasons to say, "there was no other way for us to act" or "there was no reason for us to act differently".

Phil - What things can we actually do to address some of these problems?

Jana - This might well seem like an unresolvable problem right? Because on the one hand we are talking about a dialogue or conversation between science and politicians, and that conversation should also involve the public. On the other hand, we are talking about extreme situations. But then I think one of the ways in which this could be solved in the longer run is really to make the science-policy nexus more transparent and more open to the public. What does this mean? On the one hand, the composition of expert panels should be open; so the information about expert panels, who is on them, how they make decisions, how these decisions are communicated with policymakers, should be transparent. On the other hand, politicians also need to start being more accountable to the public. So they should come out in the open and say why is it that they chose to act on certain kinds of advice and not on other kinds of advice.

Phil - So rather than just, "we've been following the science", you'd like to see, "here's what we've actually been listening to and here's why we've made that decision".

Jana - Exactly. And I think another thing that really needs to change is this whole 'follow the science' idea or concept. When you look at it, what it's actually signalling is "we are not leading". Because if someone follows, clearly they are also not leading. So in that sense it's a way of avoiding responsibility. I think that that needs to change, because I think it needs to be completely clear that when politicians make decisions, they should be able to be held accountable.

53:31 - QotW: Do we all have the same skin sensitivity?

QotW: Do we all have the same skin sensitivity?

Eva Higginbotham felt out the answer to this question from Matt...

Do all humans have the same number of nerve endings in their skin, and if so, do those of us who are bigger, either taller or fatter, have reduced sensitivity in a given area of skin?

Eva - Ooh, something of a touchy subject there! Our skin has lots of different types of specialised sensory nerves that let the brain know what’s going on anywhere on our bodies. But how does that translate to actually feeling something? I put the question to Professor Francis McGlone of Liverpool John Moores University, he’s an expert in all things touchy-feely.

Francis - We can feel the sense of touch because of sensory nerves that have mechanoreceptors on them, which respond to the physical stimulus of touching something or being touched. We have more densely packed mechanoreceptors in the fingers and lips, and less on the torso or limbs. This can be visualised with Penfield’s famous homunculus - which is a model of a human body where body parts are different sizes depending on how much of the brain is devoted to ‘sensing’ that body part - the hands, lips, and tongue are very large in comparison to the arms, legs, and torso.

Eva - Evan_au on our forum had also heard of the homunculus - though that’s a new word for me! So it’s thanks to mechanoreceptors in our skin that we can feel the sensation of touch, and the number of those nerves you have going to a certain body is called the ‘innervation density’ of that body part. But how does this relate to size?

Francis - If you have naturally bigger lips or fingers, then the innervation density will scale up to fill the available space. But tactile acuity, which is your ability to detect a specific physical stimulus such as a gentle touch, will remain the same – so size shouldn’t matter.

Eva - So human to human, big or small, we should all have about the same sensitivity in the same body parts. But what happens if you get bigger, like through gaining muscle or pregnancy? Would you still have the same level of tactile acuity as before you expanded? Well, Francis says we don’t actually know - yet!

Francis - One way this could be tested in the lab by measuring the sensitivity of a pregnant woman’s stomach in early vs late pregnancy. Altogether, all humans have about the same number of nerve endings in the skin, although they are more concentrated in certain parts of the body than others, though whether overall sensitivity changes with body size, this remains to be seen.

Eva - So still somewhat of an unknown - I smell a recruitment-drive for a study coming on! Next time, we’ll be going with the flow to find the answer to this question from Rakesh

Rakesh - So typically when electrons flow for the electric current, do they come out from the atoms and flow as electric current? Is it not true that when electrons come out from atoms, light and energy is released? So why don’t electric wires change their colours?

Related Content

- Previous Do we all have the same skin sensitivity?

- Next Maiden Flight

Comments

Add a comment