Titans of Science: Sarah Parcak

Sarah Parcak was born in Bangor, Maine on the 23rd of November 1978. She attended Bangor High School before reading Egyptology and Archaeology at Yale University. She then studied here in Cambridge under the supervision of the world-renowned Egyptologist Barry Kemp. After that, she was a teacher at Swansea University and then also at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

She pioneered the use of tech to advance archaeology, including the use of detailed satellite images, which has earned her the nickname “The Space Archaeologist”. Sarah's discovered literally thousands of forgotten settlements and tombs, including the famous Egyptian city of Tanis, which was immortalised in Raiders of the Lost Ark...

In this episode

02:02 - Sarah Parcak: Discovering Ancient Egypt

Sarah Parcak: Discovering Ancient Egypt

Sarah Parcak discusses the early influences which inspired her fascination with archaeology and the Ancient Egyptians...

Sarah - I've been interested in archaeology and ancient Egypt ever since I was a small child, growing up in Bangor, Maine in the 1980s. It's not like we had the internet and endless YouTube videos, and certainly not cable, but we lived across the street from the Bangor Public Library, which I celebrate whenever I can. The librarians there helped to find me books on ancient Egypt.

I think having a grandparent who was an academic got me interested in the field generally as well. My grandfather was a forestry professor at the University of Maine in Orono. And as a result, every weekend we lived close to them and we would go visit them often.

We would spend as much time as we could outdoors. So I developed a love of being outside from a very young age and exploring. My grandparents certainly encouraged that. My parents to this day don't know where my interest in Egypt came from. They said one day I just started talking about it. And when I was five or six years old, whenever I lost my first tooth, the Tooth Fairy brought me what even now I think is a really good book on ancient Egyptian history.

And that just got me started. And then I had the chance to study Egyptology and archaeology. There's a gentleman sort of like Barry Kemp in the US. His name was William Kelly Simpson, an eminent Egyptologist who studied language and religion and culture. And I had the chance to work very closely with him. I was his research student all the years of my time at Yale. He was extraordinary. So yes, I was very blessed to be able to work with Kelly and then Barry in graduate school.

Chris - But when did you first set foot in Egypt then? And did that crystallise all that interest you'd had from what you'd learned at university? We all know it's a bit like driving a car.

You never really learn to drive and know that it's for you or not for you until you actually get behind the wheel and hit the open road. When did you first go to Egypt and then say, this is definitely my thing?

Sarah - So I had the chance to go in the summer of 1999. So almost exactly 26 years ago. It's weird saying that number. That feels like a long time and yet it was yesterday. And so I was joining this field school that was run by Dr Redford and his wife Sue Redford out of Pennsylvania State University. So I went about two and a half weeks early, figuring, oh, I'll just travel around by myself. And the 46-year-old me is looking back at 28-year-old me and going, you are out of your mind. What are you doing travelling around Egypt by yourself at that age? And I just went and did it.

I think the world maybe was a little safer. Maybe I was just a little more naive. And when I was down in Aswan, I was on the island of Philae and I met this lovely couple, a woman from Taiwan and her husband who was German. And they were leading a tour of what seemed like very wealthy Taiwanese women. They said, oh, you're a student travelling around by yourself. You should come travel with us. We're taking a cruise down the Nile. And I said, look, I've counted every last penny or pound. I'm staying at roach motels. There is absolutely no way I can afford five days on the Nile and flying to Abu Simbel. And they said, no, no, come meet everyone. We want everyone to meet you.

And so I went over and they spoke to all these Taiwanese tourists and Chinese, and all at once they all went, "Hello, Sarah." And they later on invited me to come join them on their boat. And I went and it was a floating five-star hotel. And I said to them, look, I can't afford this. The budget for one night on here is the budget for my whole trip. And they said, look, there's already a younger woman who's here. We're worried because she's on her own and she's a little older than you, not much. Why don't you be her roommate and give us a couple of hundred dollars to cover basic expenses. And so it was this magical, otherworldly, coincidental adventure. And it felt like a door. And it felt like these winds from thousands of years ago appeared and sort of blew me through it. And I thought, there's something about this country that's different, that it felt so welcoming and warm.

I've actually never shared that story before publicly. And I just said, this is the place I need to be. And I asked them afterwards, why did you do this incredibly generous, wonderful thing for me, the stranger that you meet, the student you meet on an island? And they said, we just had a sense about you. We thought you would take this ahead and you would spend the rest of your life sharing your love of Egypt with everyone.

Chris - Do you think then that you might have ended up not being an Egyptologist? You could have been an archaeologist, but working somewhere else entirely if it hadn't got hold of you the way that that experience did?

Sarah - You know, Egypt just always called to me. I remember being an undergraduate and Kelly was such a generous human. And every autumn he would invite all the first-year students in the residential college where he was a fellow and I was a student to his estate in Katonah, New York. Kelly had been married to one of the Rockefeller daughters. She'd passed away many, many years before. And then I got to go into his office and it was 20 feet tall, old leather chairs, heavy with pipe smoke, antiquities in different places where he clearly bought them over time. And I just thought, I'm done. This is it. This is the life I want.

There's something about this that speaks to a part of me and it feels like I've been waiting my whole life to get here. You never know, right? When you go into the field, sometimes people start digging and they hate it because it's rough, it's hot, you get sick.

You're far away from home. But I just always felt at home in Egypt and the people there are so wonderful and warm and gentle. So it's another home for me and it felt that way from the first time I went.

08:10 - Sarah Parcak: Pioneering satellite Egyptology

Sarah Parcak: Pioneering satellite Egyptology

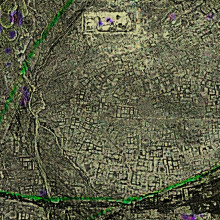

Sarah Parcak speaks to Chris Smith about her work deploying satellite imagery to the task of finding new sites of interest for archaeologists...

Chris - What's it actually like when you're on a dig in Egypt? It's a pretty harsh environment, isn't it? I mean, it's not only ridiculously hot, but it's like being sandblasted with sand. It's getting into every nook and cranny of your body and you're sweating. It must be pretty horrible. You must have to dig deep, excuse the pun, in order to put up with that day after day. You must really love the subject in order to tolerate that.

Sarah - Yes, it's hot. Yes, there are flies. Yes, there's sand blowing around. But there's something about the pace of a dig and you never know what's going to pop up. You may find a beautiful little bead or part of an inscribed fragment. I've had days or weeks where nothing has appeared, but you're so busy recording all the information, it's fine. I try at least once an hour to pop my head up from wherever I'm working just to look around and just kind of pinch myself. There's still that five- or six-year-old little girl inside you who got that book from the Tooth Fairy. This is your dream and you're living it. You just need to feel grateful and take that gratitude and pour it into the work you're doing.

Chris - So, how did the space element to this come about then? So, you love doing the on-the-ground stuff, getting your trowel into the ground. I thought you were going to say you didn't love it so much and that's why you went after the cool air-conditioned environment of computers and that's how it happened, but clearly not. So, why did you end up looking at satellite pictures?

Sarah - So, you know, getting back to my grandfather, he was famous in the field of forestry because he was one of the pioneers of using aerial photography and aerial photogrammetry for forest mapping and species identification. He's the reason I took my first remote sensing course as an undergraduate and I thought, well gosh, Grampy passed away a couple of years before. Grampy did this. I wonder if anyone has really done this for Egypt or archaeology. Maybe I'll take this course and see. At the time, not many people had applied it to the field of Egyptology.

So, I took that with me into grad school and started developing tools and techniques for archaeological site identification. For me, the best part was I could go and survey and map the sites that I'd found as part of these excavations. So, I was able to do that in the east Delta with my then boyfriend, then fiancé, and obviously now husband. We'd excavate all week and then I'd go off and do survey work on the weekends, and the same at Amarna. I could help with excavations but also go and do survey work on the west banks.

Chris - So, talk us through then how this actually works. What images do you get from space and how do you then use that to find stuff that we didn't know was there already?

Sarah - There are two different kinds of satellite imagery that we use in the field of remote sensing. We're either using what's called passive or active satellite data. So, what do I mean by that? Passive satellites are like Google Earth. A passive satellite is like a camera. It's circling the Earth, taking pictures of what's below and recording information in different parts of the light spectrum — the near, middle, and far infrared, the visual part of the spectrum, and in some instances, microwaves. Then you can take that information and it comes in layers. Each slice is almost like a big sandwich — lettuce, meat, bread. Each slice represents a different part of the light spectrum. Certain features show up or disappear depending on which layer you're viewing. Visual features like houses and roads show up well in the visible spectrum. Vegetation shows up best in the near-infrared due to the chlorophyll. When processing the data, features can appear more clearly due to differences in soil moisture or buried structures.

Active satellite imagery is different — the sensor sends energy down, like radar or LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging). LiDAR can penetrate forest canopies and reveal what's beneath, creating a digital elevation model. That’s how we’ve revealed tens of thousands of unknown sites in places like the Guatemalan rainforest.

Chris - So, what was your first ‘wow’ moment then? When you thought, right, I'm going to do this for Egypt because it doesn’t look like many people, if anyone, had. You do this, what happened next?

Sarah - I think what really hooked me was during my PhD. I did a big survey project for the first half of my thesis in the east Delta around the site where my husband Greg had been working, a site called Tell el-Balamun, dated to around 2,600 years ago. Using mostly NASA datasets, I looked at the actual chemical signature of archaeological sites.

I thought, we've got all this known site data — what if I inputted this into the satellite imagery, developed tools and techniques, and went from the known to the unknown? That's what we do in archaeology anyway. When I processed the imagery, I had maybe 60 to 70 features pop up that weren’t in any known database. That’s what really kicked me off visiting those sites.

Chris - So, you were actually finding stuff, you were going to places, you began to get results. So, you must have thought, wow, this is really cool. I'm finding new things that people didn’t know were there. That must have been pretty exhilarating.

Sarah - It was super exciting. Not everything was a win. Sometimes I'd go to a site and it would just be a big pile of dirt. Or yes, there was a site, but it was covered by a modern cemetery. I could pick up a little pottery, but there wasn’t much else. For me, the process — the iterative process of science — was also very exciting. Really being critical of what worked and what didn’t. I would then go back, refine things, try new approaches and tools. What's the real method here? Why doesn’t this one work?

For me, yes, it was exciting mapping all these new sites and collecting pottery and conducting settlement pattern studies. But I’m a dorky nerd — the process was, and still is, fascinating. Figuring out how you can put all these tools together at different levels of resolution, both spatial and spectral, to understand what each type of data reveals — or hides.

15:54 - Sarah Parcak: Uncovering Tanis, a tale from Indiana Jones

Sarah Parcak: Uncovering Tanis, a tale from Indiana Jones

Sarah Parcak tells Chris Smith about one of her biggest contributions to her field, mapping the ancient site of Tanis, as featured in Raiders of the Lost Ark...

Chris - How did Raiders of the Lost Ark and Tanis come into this then?

Sarah - So, you know, like every child of the 80s, every Friday night my parents would get a movie for my brother and me and pizza. It was a big deal in those days. And we'd rotate through: it was either The Princess Bride, The Dark Crystal, The NeverEnding Story, or Raiders of the Lost Ark. I love that movie. It's still one of my favourite films. Yes, I know he's problematic, but also he is a movie character. There are a lot more problematic academics in the real world I think we should be worried about. Anyway, I heard about Tanis, and then, of course, I studied it as an undergraduate and then in graduate school.

Chris - So it was one of those places known about, as in it was documented, but not known where?

Sarah - Right. So we knew Tanis has been worked on as a site for well over a hundred years. What's interesting about Tanis is there was an amazing discovery made just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. So at Tanis, it was Egypt's capital in Dynasties 21 and 22, so about 3,000 years ago. All these kings who ruled from Tanis were buried in and around this very large temple complex that's in the northern part of the site. And when they were excavated, they uncovered beautiful tombs that were full of gorgeous jewellery and silver sarcophagi and coffins. So these pharaohs are known as the silver pharaohs because, unlike later sarcophagi and coffins, which you see made of gold, theirs were made of silver. And because of the outbreak of the war, it's just not a discovery that is as well known as Tut. But if you go to the Cairo Museum today, they have a whole room filled with the finery from Tanis.

The temples have been excavated for a long time by the French team, and we knew roughly where the settlement was, but no extensive work had ever been done on it. So I was drawn there. We got very high-resolution satellite imagery of the settlement of Tanis, processed it, and we were able to see the outlines of almost the entire settlement in different phases of its construction. You can see barracks, streets, houses. It has a very similar layout in many ways to Amarna, and even a place where there could be potential palaces. So I collaborated with a French Egyptologist named Philippe Rousseau. He excavated one of the houses again as a ground test, and it was a pretty close match to what we'd seen from the imagery. So yeah, I was definitely drawn there by Indiana Jones, but did not expect that we would find this whole outline of the settlement. That was really exciting, and I hope a genuine contribution to the field of Egyptology.

Chris - A lot of this is now desert, isn't it? So how would it have been different back in the day? And was it desertification that did for those civilisations, or did these settlements just get abandoned and then the desert encroached later? Do we know?

Sarah - Sites were abandoned for lots of different reasons. In some instances, the climate would change, but I think many sites in Egypt were abandoned, at least for a time, because of the Nile River. The Nile – it's hard to get a sense of this today because of the Aswan High Dam – doesn't shift like it did in antiquity, but it did. It was every bit like the Mississippi. It would have meandered and had oxbows. If a city was located next to the Nile, it would have thrived, right? It’s the epicentre of trade, information, goods coming into the city, goods going out from the city, and then the Nile shifts – and that’s it, right? There's no port.

The city can't function particularly well, and so maybe over time it gets abandoned. I think in Egypt, we definitely see periods where climate change has a pretty serious impact on settlements. One of the periods of time that I've studied and written about, starting with my PhD, is around 2200 BC, so the end of the Old Kingdom. What happens around this time is something called the 4.2k BP event, or the 4,200 years ago event. It's suggested that, potentially because of a series of solar flares or solar radiation, the weather around the world was pretty seriously impacted – sort of like a mass El Niño effect. What happened is that the monsoon rainfall that filled up the Blue and White Nile basins and caused the Nile to flood every year just didn’t arrive at the same levels as before. What you see, starting around the end of the Old Kingdom, are a series of droughts.

Chris - Are these the biblical droughts? Is this what Joseph and his family, when they had seven lean years – is this what he foresaw?

Sarah - Maybe. It's debated. This happened before his time. Because every year, the Egyptians relied so heavily on the floods, it had to be like Goldilocks. It couldn't be too much, it couldn't be too little – it had to be just right. That's the role the king served. The king preserved Maat, this sense of balance. His job was to ensure that the Nile flooded every year, and that's why offerings were made at temples. Anyway, you had a series of disastrously low Nile floods. There were no crops or greatly reduced crops. People started abandoning these villages and moving into cities, which is something I saw as part of my PhD thesis. Pyramid construction stops, foreign expeditions stop.

We see this degradation of art and great social strife going on. This changes when the monsoons pick up again and there's regular flooding. We see this in the New Kingdom, which is about 2000 BC, so a couple of hundred years later. Egypt goes through this great period of upheaval, which is interesting now because the world is very similar to what's happening today. To your question, these are the things we study. We look at why sites were abandoned in certain periods of time and for what reasons. It wasn't all climate change – there were social, political and economic reasons too. Most sites in Egypt were fairly continuously occupied going back thousands of years. Even today, most well-known sites have people living on them or next to them.

22:43 - Sarah Parcak: What the Egyptians did for us

Sarah Parcak: What the Egyptians did for us

Chris - There was a terrific programme the BBC made, a series they made a number of years ago called What Did the Victorians Do for Us? They looked at all of the incredible engineering. It occurred to me as I was watching that a lot of that we inherited from our forebears thousands of years ago. I suppose I put to you the question: what did the Egyptians do for us? As well as giving us this rich archaeological legacy, what things still exist today or techniques or doors were opened by the kind of science and maths and knowledge that these people had?

Sarah - Someone I've spent a lot of time studying – Cleopatra. To this day, she has an extraordinary influence on our world, on how we imagine the past and interpret the past and think about the role of women. I think they – maybe my colleagues who work in other cultures and other places would disagree with me – I think they gave us our bureaucracy. They really figured out layers and layers of organisation and management. If any of you have problems with your line managers and are having issues with bureaucracy and getting permits or permissions or a licence for something, I think you can blame the ancient Egyptians. They developed it there. Without that bureaucracy, the pyramids wouldn't have been built. What made the pyramids what they were – and still are to this day – was this whole system of management: of quarrying, of trade, of delivery, of workers’ health, food, managing estates in the Delta to produce enough beef to keep the workers fed. For me, I think it's bureaucracy. That's the real legacy of ancient Egypt in our world today.

Chris - It sounds like you've embraced a lot of their techniques. A little bird told me you're a very good baker. Is that true?

Sarah - Yeah, I love baking. This is something that actually started in Cambridge. I was a grad student. I was very lucky to have funding, but it wasn't a lot of money. I had to learn how to cook and how to bake. One of the lovely things about being at Cambridge then – I hope this tradition still continues – all of us were in the same boat: not a lot of money, just getting by. We would gather for a night or two a week, and everyone would bring a dish to share. Of course, you had people from all over the world, and you never knew what anyone would bring. It all worked out.

There were always a couple of starters, a couple of mains, and some desserts. I really just got into cooking and baking when I was there. Bless Barry – I wouldn't be where I am without him – but I think every single person who's ever been to Amarna would tell you the same thing, and that is that he was not concerned with food in the way that we are concerned with food. The grandfather of Egyptian archaeology is a guy named William Matthew Flinders Petrie. At the end of every season he worked in Egypt, from the 1880s onwards, he would bury all the cans that were left over. When he started his next season, he would dig the cans up and throw them against the wall, and the ones that didn't explode, he would eat. Barry carried on in that tradition. I could always rely on our dig seasons at Amarna to keep me trim and fit for the rest of the year. Obviously, the archaeology was wonderful, and he cared about us a great deal. Food was not a priority for him. I promised myself that if I ever ran my own projects, I would make sure that my team was well fed. I love baking and sharing treats with our neighbours. It's interesting too, because I think a lot about, in the work I do in the field, how did people feed themselves? How did they survive in all these places? It's just something else to connect the work I do to how I live today and what life was like a long time ago.

Chris - Because people have recreated some of the ancient recipes that that famous bureaucracy you reference led to being documented. There was food, there was drink, and people have tried to reinvent some of these recipes. Apparently, some of them are all right. Have you not gone down that path?

Sarah - I haven't personally experimented with more ancient baking. Certainly, Dr Mark Lehner at Giza has done really amazing work partnering with bakers and brewers and trying to recreate ancient Egyptian beer, because, of course, that's most of what the workers would have consumed alongside bread. The bread would have been very, very dense and calorie-rich, and they would have needed those for their work. I remember one programme I did for the BBC, actually, when our son was – I think I was about three and a half, four months pregnant with him – filming a documentary on the Roman Empire. We were very lucky, we were working at a site in Tunisia, and the BBC had flown in this delightful woman whose name I cannot remember right now, I wish I could – and her expertise was baking and cooking in the Roman world. She brought all of these gorgeous reproduction Roman bowls into the field. She'd gone to a market in a village and gotten all this food, which was the same as the food that had been consumed 2,000 years before. She brought garum, which is the fish sauce that the Romans used – there are many different kinds of garum – and she had cooked these goat cutlets in garum. I'll never forget, I'd been a vegetarian for years, and the smell of these cutlets cooking on an open fire in this garum – I was at the point of my pregnancy where I was getting really hungry.

The team knew that I hadn't eaten meat, but a voice in my head said, you will eat all this meat right now. I think they had to cut it from the show because I was like a barbarian. I looked at the guys, who were all very excited about the meat, and said, I'm sorry, I'm eating all of this food. I was gnawing at it; there were juices running down my face. To this day, that will be the best thing I've ever eaten in my life. If she's listening right now, I apologise for not being able to remember your name. You're amazing. I've never thanked you properly. Since then, I've eaten meat. The people who do that work are extraordinary. I have such enormous respect for them.

Chris - Well, that's certainly food for thought and a wonderful thought to end on. Sarah, it's been a pleasure. Thank you for telling us all about why you're a titan of science – and space science archaeology specifically.

Sarah - Thank you so much for having me. This has been wonderful.

Comments

Add a comment