In this episode of The Naked Scientists, we are looking at the outbreak of monkeypox - mpox - in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and fears that it could spread internationally…

In this episode

Where does monkeypox come from?

Mike Weekes, University of Cambridge

The monkeypox virus was first identified in the late 1950s, when it was isolated from monkeys; hence the name. Which is actually a misnomer, because the virus is actually an infection of small rodents and only accidentally jumps into bigger animals when the opportunity presents. In the decades since its discovery, small numbers of human cases and outbreaks have been documented periodically, most of them within the two parts of Africa where the two main forms - or clades - of the virus are centred. The disease had previously never circulated outside the African continent, and only sporadic cases were picked up internationally in travellers returning from endemic areas. But two years ago, things changed with a massive outbreak that ultimately affected tens of thousands of people across tens of countries. That outbreak, which circulated chiefly among gay men and has since been reined in, was caused by the west African - or clade 2 - form of the virus and marked the first time the agent had spread significantly in communities outside of Africa. Now, since late 2023, another major outbreak has erupted, this time centred on the Democratic Republic of the Congo and caused by the allegedly more aggressive central African - or clade 1 - form of the virus. So far it’s affected thousands of people, including children, and claimed hundreds of lives. Its means of spread, and possibly its infectivity, may therefore be different. It’s already spread to neighbouring Africa countries and could travel farther, prompting the WHO to declare a public health emergency of international concern.

We’ll hear more in a minute about the situation in the DRC - and the international response. But first, what does monkeypox look like when we catch it? I went to Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge to meet Cambridge University’s Mike Weekes, professor of viral immunology and a consultant in infectious diseases…

Mike - A patient with monkeypox would typically be somewhat unwell. They'd have a fever, they'd have a sore throat, a typical rash, which is a telltale sign of monkeypox and they might also have muscle aches, back ache, glands up in the neck.

Chris - How quickly do those features come on after a person is exposed to someone who's effectively given it to them?

Mike - The typical incubation period, if you'd like, is between 5 and 13 days, most often between about 7 to 10 days.

Chris - And how long do those symptoms last?

Mike - Overall, the symptoms can last 2-4 weeks. The longest thing to last is the rash because that goes through a number of stages. It starts as a macule, that flat red spot, becomes a papule, a raised red spot, and then what we call a pseudo pustule, which you'll have seen pictures of on the news, which are raised spots that look like they're filled with pus but are actually solid.

Chris - People who catch it, where do they get it from? How do they pick it up?

Mike - There's a number of routes. The original virus that we saw spreading around the world in 2022, which we call Clade 2b, was predominantly transmitted by sexual contact. The most recent Clade 1b rash that has started in the Democratic Republic of Congo seems to be transmitted not only sexually but by lots of different forms of close contact. The most risky exposure is the exposure to the rash itself and this is the biggest way for the virus to be transmitted, by contact with the rash, and particularly after you've come into contact with a rash touching your mouth or your eyes or any of your mucus membranes, but it can also be transmitted by the bits of the rash that have fallen off. So if you have contact with linen or clothes, or even if you accidentally prick yourself with a needle that's been exposed.

Chris - That means then there are lots of ways that a healthcare setting has to be cautious when they're dealing with possible cases of this to make sure that it doesn't spread to other patients or to staff. Walk me through how an average hospital who might see a case of this would handle it to minimise those sorts of risks.

Mike - You're quite right. So mpox Clade 1b is classed as a high consequence infectious disease, and that means that it can relatively easily be spread within a hospital or within a community, and also it may have an appreciable mortality rate. Other examples of high consequence infectious diseases are things like Ebola, certain strains of flu and MERS. The first thing to do is to isolate the patient somewhere safe, and so what you would typically do would be to put them in a negative pressure room, and that means air goes into the room because the air pressure in the room is lower than the air pressure outside, and then when it exits, it goes through a series of very powerful filters to get rid of any viruses. The other thing that we have to do is have adequate PPE, and for a high consequence infectious disease the principle is to cover up all exposed skin and to filter the air. What you have to do is wear a hood, an FFP3 mask, gowns to cover your whole body, boots, and at least two pairs of gloves.

Chris - And are doctors who do the sorts of job you do, are they prepared for that? Is the UK's level of preparedness quite good? Obviously we've had a bit of a trial run with this because two years ago we saw this initial rash of cases, which was the Clade 2b, now we've got this slightly different form, but it presumably has given us some grounding in how best to tackle this?

Mike - Both from the Coronavirus pandemic and the Clade 2b mpox outbreak, we've had a lot of preparedness and so we know very much what we should do, exactly how we should wear PPE, and exactly how we should treat patients like this. We have a network around the country of hospitals prepared to deal with high consequence infectious diseases.

Chris - What about dealing with people who might have come into contact with a case but haven't yet got it? Is there anything we can do for them? Or how do we handle those sorts of contacts?

Mike - So if it was a very significant contact then the main thing would be to isolate the patient and to warn them of symptoms they might expect, but that's pretty much it. Basically, you are not infectious until you develop symptoms. There've been a very few cases of infection being transmitted before the development of symptoms. This mpox is really not the same as coronavirus where you became most infectious before you develop symptoms. Now, you are infectious when you develop symptoms and particularly when you develop a rash. You know you have it. It's not really transmitted without symptoms.

08:53 - What does mpox do to the body?

What does mpox do to the body?

Geoff Smith, University of Oxford

What kind of virus is mpox, and how does it get into the human body? Geoff Smith is a leading expert on poxviruses at the University of Oxford…

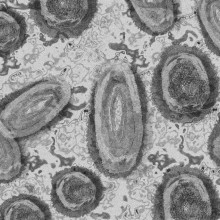

Geoff - So monkeypox is a pox virus and a member of the orthopoxvirus genus. So other members of that genus include variola virus that causes smallpox, cowpox, and vaccinia virus, which was the vaccine used to eradicate smallpox. And these are all big DNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm and are quite closely related genetically. So that infection with one will confer subsequent protection against infection by any other member of that virus genus.

Chris - Where do these viruses normally hang out? I know we call it monkeypox, or now we've rebranded it mpox. Is that a misnomer? Because allegedly monkeys are not the host?

Geoff - Yes, it's a misnomer. It was called monkeypox virus because it was isolated first from a monkey, but that's not the natural reservoir and the exact reservoir is not known, but they're likely to be rodents in different parts of Africa, either Central Africa or West Africa.

Chris - So what is the biology of the virus then? If it's normally in these rodents, what do we think the normal pattern is in terms of it spreading to other creatures, causing disease, et cetera?

Geoff - Well, presumably in the rodents in which it is endemic, it won't cause devastating disease because if it did, then it would kill all the hosts and it wouldn't be able to survive. But monkeypox virus has got a wide host range and can clearly infect other animals, including primates and us. And it's the ability of the virus to spread from the natural rodent reservoir to humans. That is the problem.

Chris - And people talk about there being different variants or versions of these clades. What does that mean and where are they?

GGeoff - Well, there are broadly two clades that are separated geographically. And the clade 1 viruses that originate from Central Africa, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, are more virulent than the clade 2 viruses that come from West Africa and which cause less disease in humans. So they're defined by their genetic relatedness, by sequencing the genomes you can tell quickly to which clade a monkeypox virus belongs.

Chris - When they cause disease in an individual, whether that's a monkey or us, how do they spread between individuals do we think?

Geoff - The spread between individuals has always required close contact? So generally, when monkeypox was causing small, sporadic outbreaks in Africa, the outbreaks tended to be self-limiting because the virus did not spread efficiently from person to person. So you may get one or two or three transmissions within a close group, possibly within a family, but it would not go further than that. And so the infections would die out and be self-limiting. And then in 2022, when this big epidemic started, it went global and the viruses originally came from West Africa. The virus then got into the population of men who have sex with men. And so the virus was transmitted by sexual means, and the biology of the virus hadn't changed. It's just that sexual contact is one form of close contact and that's how the virus was spread.

Chris - And once a person catches it, what's it actually doing in the body? What's the process or the mechanism by which it causes disease?

Geoff - Well, that hasn't been looked at in great detail in humans, but it gives a disease which looks very similar to smallpox in that the virus will enter either via a skin abrasion or possibly by the respiratory tract. And then after a series of replication events, it will spread through the body and eventually go to the skin where the characteristic skin blisters are formed. And it's from those skin lesions, either on the skin or in the oropharynx, that the virus can be spread to be transmitted to new people.

Chris - So how does it make a person ill, can it get into almost any cell type in the body or is it hitting a limited repertoire of tissues? And when it does, why does a person actually get the symptoms that they get? Do we know?

Geoff - No, we don't really know the details of that. But the virus can clearly infect a range of cells, including epithelial cells, but likely also white blood cells that it may be able to spread via those throughout the body.

14:06 - How is the monkeypox outbreak being handled?

How is the monkeypox outbreak being handled?

Boghuma Titanji, Emory University

The current, massive outbreak of monkeypox began earlier this year in the Democratic Republic of the Congo - the DRC. This country is about the size of western Europe, and it’s been beset by civil war, corruption and an exploding population. It neighbours 9 other African nations, and DRC’s health officials have struggled to contain the recent monkeypox virus within its borders. The problem - as Maria Van Kerkhove mentioned earlier - is particularly acute in the eastern part of the country where a United Nations force is fighting an uphill battle to keep the peace. So, what impact has the disease had on the DRC, and how is the current caseload there being managed? Boghuma Titanji is a Cameroonian-born doctor and an infectious disease specialist at Emory University in Atlanta…

Boghuma - Since the beginning of this year, the DRC has seen an increase in case numbers of mpox and it's reported that they now have about 17,000 cases with an estimated 550 deaths. And it is this surge in cases that has really triggered the international response that we're currently witnessing. And there's certain things that make this outbreak in particular stand out. Firstly, when you compare the number of cases that the DRC had reported, where mpox is concerned in 2022 and 2023, the number of cases this year actually marks 160% increase in the numbers of cases being recorded. So this is a really sharp increase in cases. Additionally, the strain of mpox that circulates in the Democratic Republic of Congo is called clade 1, and historically has been associated with more severe forms of the disease as well as a higher mortality level, which also raises the concern that we are seeing more cases of a more virulent strain of the virus. And then thirdly, we are also seeing it spread in a different manner compared to how it spread historically. And then the fourth and final piece is that beyond the DRC, we have now seen exportation of clade 1 virus to other African countries that are neighbouring countries to the Democratic Republic of Congo. And these are countries that historically had never reported mpox infections before. Again, highlighting the risk that this could spread to a broader scale and cause a more extensive outbreak. And of note that we know that Sweden has reported a case of mpox clade 1 in a returning traveller. As has Thailand. So really indicative of the real threat that it poses if we don't contain this effectively in the DRC.

Chris - What do you think, Boghuma, is the mechanism of the emergence all of a sudden? I guess the question is why here as in DRC and why now in these sorts of numbers?

Boghuma - When you look at the historical trends of how mpox has spread through the years, it's important to remember that really the countries that have mpox circulating in an endemic manner have been witnessing cases for the past five decades. The first human case of OCH was described in 1972 in a 9-year-old child in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And since that time, we have seen a steady increase in the numbers of outbreaks and in the sizes of these outbreaks. The reason for this is several fold. I think the primary reason is that first of all, smallpox vaccination, which is vaccination for another orthopox virus known as variola, which was the causal agent of smallpox, stopped in the late 70s to the early 80s in most African countries. Now these vaccines can offer cross protection for other orthopoxviruses, including mpox. The interruption or stopping of the smallpox vaccination in the early 80s means that a lot of people born after 1980 in these African countries are not immune to orthopoxviruses. So you have a large vulnerable population. Additionally, you have to imagine that the population has also grown significantly over that time, and there's also been increased movements of people. So all of these factors in combination essentially allow the virus an opportunity to infect a more vulnerable population as immunity wanes. But also because people are more interconnected and the population has grown, it means that there are also opportunities for more sustained spread and larger outbreaks.

Chris - With those considerations in mind. What therefore needs to be the response both locally in the short term, and that means in the DRC, and then locally in the long term. But also right now across the world, what do we need to be doing to be on our guard and also to help to reduce the risk that this continues to amplify in the way that it is.

Boghuma - So the first thing about the response is really trying to understand the drivers of the different outbreaks that the DRC is currently witnessing by better characterising the sources of zoonotic transmission, but also better characterising the drivers of human to human spread. Are these all primarily sexual contacts or are these close contacts of people who are infected in overcrowded settings, et cetera? And in order to do that, I think that the first thing would be to make sure that there's adequate resources for testing as well as contact tracing. Remember at the beginning of our conversation, I mentioned that the DRC has reported an estimated 17,000 cases since the beginning of this year. Now only 10 to 15% of these cases have actually had confirmatory testing demonstrating that they have mpox. So if you cannot confirm an infection, it makes it harder to trace and identify who else may be impacted by that infection. So surveillance through robust testing and contact tracing would help researchers on the ground define how the virus is being transmitted, who is being impacted, and with that knowledge you can then craft interventions to effectively interrupt the spread. Now coming to the interventions that can be utilised to interrupt the spread, we have several tools at hand. We know that the vaccines that have been developed for smallpox will confer a certain degree of protection against mpox infection and also have the possibility of attenuating mpox disease in people who have been vaccinated. So if you define who is being impacted, the next step will be to craft a vaccination strategy that is adapted to prioritise those that are most likely to come in contact with the virus and get an infection. And then the third piece of this, obviously, which is absolutely central to any response to an outbreak, is information and education. We saw in the 2022 outbreaks that a huge component of the public health response that led to the containment of that outbreak of mpox was changes in behaviour within populations that had high incidents of mpox. So if you educate the communities about what the disease looks like and how it's spreading, then you can provide them with tools that allow them to modify their behaviours in manners that would have the potential to reduce spread.

22:01 - Can monkeypox be treated?

Can monkeypox be treated?

Michael Marks, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

How might it be possible to prevent people from getting the virus in the first place? And manage those who are unfortunate enough to contract it? Here’s Michael Marks, a professor of medicine at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and a consultant in infectious diseases at University College London hospital…

Michael - So the first thing to recognize is that there is a range of how unwell people are. Many, many individuals with mpox will be really very mildly affected and we have seen in previous outbreaks in the UK and elsewhere that probably 90-95 out of 100 people can be managed at home just with what we call supportive care. So that's simple things like analgesia, dressing the wounds, keeping hydrated. And then there will be a smaller proportion of people who become very unwell. And we know that those are individuals who are more likely to, for example, have problems with their immune system such as HIV infection. Or in the current outbreak in DRC, children are more severely affected. Those individuals may need admission to hospital for specialist care. We don't have any drugs that we know definitely work for mpox. There are some drugs that are being tested in studies to see if they can help people get better more quickly or indeed reduce the risk of dying. But those are all experimental treatments at the moment only being studied to see if they are helpful.

Chris - One of those drugs. An announcement was made a week or so ago suggesting that people just did better when they were in a trial in hospital, but the drug didn't make much difference. But some commentators argued that's because they gave the drug too late. If we'd gone in earlier with the drug, it might have made a bigger difference.

Michael - Yeah, so this is a drug called Tecovirimat or TPOXX, that's the name the drug company uses. And you are right that in the study that was recently announced, everyone regardless of whether or not they got the drug or not, seemed to do better than what is being reported overall in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And we often see that effect in studies. Just if you are generally being looked after by a big research team, you get better general care and so outcomes are better. We know that the virus is not in the blood for very long in mpox infection. And so if we think that the way this drug might work is by stopping the virus spreading around your body if it's going to have any effect at all, you probably need to give it very early in the illness before the virus is already spread everywhere. And with the eye of faith or being optimistic, if you look at the study results, people who got the drug within the first seven days of being unwell seemed to do better. So we don't know definitively, but there is probably enough there to say we should be studying the drug in people. But really targeting it at people who have just become unwell before the virus has had a chance to spread all around the body.

Chris - Is that currently the policy or is it literally only available in a research context? We don't have it generally being rolled out in places where there's disease activity? Or is that not the case?

Michael - So because it's not a proven treatment, really this is a therapy that is available in the research setting. It's not a drug that has been shown to be of benefit to all comers. And so really because there's no proven benefit, its use is restricted predominantly to further studies to see why this person benefits from the drug? Why does this person not benefit from the drug? Can we reliably identify people who if we gave them the drug they would do better than if we didn't give them the drug?

Chris - So it's an iron in the fire. It's a possible future avenue but it's not the mainstay yet. So what are we using as the main way to control the infection at the moment?

Michael - You're right. So we don't have any working antivirals yet. So really the main intervention that we have available to us is vaccination. And that is a strategy that is obviously not about treating individuals once they've already developed the illness, but about reducing risk in the first place. And there are effective vaccines that are available which, if given, can significantly reduce your risk of catching mpox. And probably even if you catch mpox despite being vaccinated, reduce your risk of becoming unwell. So they both have a direct effect, you are less likely to catch the virus and they probably protect you from becoming sick. And that's really the key intervention that we have available to us.

Chris - The current UK government guidelines are that we can try to use the vaccine in people who have been exposed. It's almost like a prophylactic measure. It gives the immune system a bit of a head start and it seems to cut down the number of clinical cases we get. Is that likely to become part and parcel of what we do in places like the Democratic Republic of the Congo where we've got big numbers of cases, we can go in and try to rein in the outbreak by protecting people who've been exposed.

Michael - So there are two broad approaches you can take. There's what we call pre-exposure vaccination. So that's taking people who are at risk and vaccinating them before they're exposed. And then there's post-exposure vaccination. The scenario you are describing, I come into contact with someone, you try and vaccinate me. Most of the data we have so far suggests that pre-exposure vaccination is much more effective. And that's probably because you're giving the body's immune system time to really respond to that vaccine and protect you. Whereas if you vaccinate someone after they've already been exposed, in fact they may already be infected and you may not fully have a chance for the vaccine to work. So the ideal scenario is that we have enough vaccines available that we can roll it out at scale to all the people who are living in areas where there are many, many cases of mpox at the moment before they are exposed. Of course, some of those individuals will be exposed and so they will effectively get post-exposure vaccination, but we really are likely to need widespread vaccination of many, many people to curtail the outbreak.

Comments

Add a comment