Will we ever return to the moon?

It's nearly been 5 decades since Neil Armstrong took one small step for mankind... But will we return again? As things heat up, Graihagh Jackson brings together the cosmically curious to unpick our the drivers behind the marathon to the moon.

In this episode

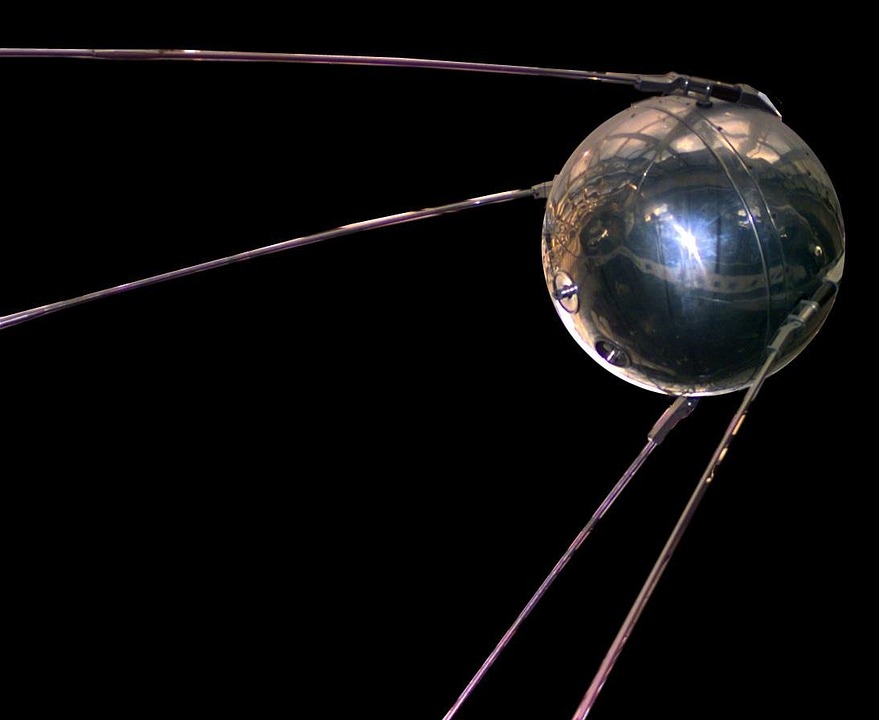

02:32 - Sputnik: The space race's opening shot

Sputnik: The space race's opening shot

with Richard Hollingham, space and science journalist, Space Boffins

It was the first Friday in October, 1957 at 19:28 that the great space began.  Sputnik was propelled into orbit by the Russians and everyone watched with awe and unease, as Richard Hollingham explained to Graihagh Jackson...

Sputnik was propelled into orbit by the Russians and everyone watched with awe and unease, as Richard Hollingham explained to Graihagh Jackson...

Richard - October 1957 with the launch of Sputnik was just a massive shock to the United States. It wasn't really just the fact that the Soviet Union had managed to put a large satellite (this is an 83 kg satellite) into orbit 560 miles above the Earth. Also the size of the rocket they used to launch that satellite. And it wasn't really about a space race, it was about the fact that if the Soviet Union could do this, they could undoubtedly launch nuclear warheads to the Continental United States, so that was a huge shock.

Graihagh - Science and Space Journalist Richard Hollingham who you may recognise from presenting the Space Boffins podcast too. But that wasn't the only thing that was shocking to the US...

Richard - The first attempt by the United States to get a satellite off the ground became known as "flopnik" among other things. It exploded on the launch pad and kind of rolled away beeping. It's quite comical to watch but it was a huge shock to the U.S. at the time and they finally managed to get a small satellite off the pad later that year.

Graihagh - So in some ways this was sort of muscle flexing?

Richard - It's totally about muscle flexing. In the U.S. they called it the "missile gab", so really great fear. I mean you have to imagine that time - the cold war, fear on both sides of the iron curtain. And so, yes, it was just all driven by politics really.

Graihagh - So Sputnik was first then but the U.S. launched their equivalent a month later, almost a bit like tit for tat in some ways.

Richard - Yes, the Americans finally managed to get a satellite in orbit. A much smaller satellite later in 1957, but then the Soviet Union still managed all the first. So, the first man in orbit, Yuri Gagarin in April, 1961. The first woman in orbit June, 1963. Now the U.S. didn't manage to get the first man ins pace until the 5th May '61 and that was Alan Shepard but that was just a suborbital flight. So it was really sticking him in this tiny Mercury capsule on top of a launcher going up and then straight back down again. They didn't have the power to get into orbit.

So if you look, certainly at the early 1960s, where you had the flight of Valentina Shcherbakova, the first woman in space in June '63. You had the first three man capsule in 1964. The first space walk in March 1965. In February 1966, the first soft landing on the moon with a robotic spacecraft. They were all first by the Soviet Union so, undoubtedly the appearance, certainly externally, was that in the early 1960's the Soviet Union was leading the way.

Graihagh - Mmm. And I suppose that was really frightening for the Americans?

Richard - It was terrifying for the americans and you have to remember, at the time, no-one knew any of this stuff, so no-one in America quite knew what the Soviet Union was doing. They had their U2 spy plane so they could see the launch sites, they could guess what was going on. They had a pretty good idea but they didn't really know what was on the minds of the Soviets. The Soviets had a much better idea about what the U.S. was doing because almost everything in the U.S. program was open and public.

I think the most interesting point in the space race is around the mid 1960s where, to all intents and purposes, it appears as if the the Soviet Union is ahead and, yes they are, they've done all the first. But that period the Americans developed the Gemini spacecraft. So over just about 18 months, between March 1965 and November 19966, they launched a series of missions where they managed their first pace walk with Ed Wright. The managed to rondevu to spacecraft in orbit, they managed to dock spacecraft in orbit. They managed to spend 14 days in orbit; this tiny cramped spacecraft around the size of the front of a Volkswagen. But they managed to do all these things very quickly, in 18 months and it's around that period where you see the United States starting to edge ahead.

Graihagh - Was it the moon landing that won the race or was there more to it than that?

Richard - Essentially the Soviet Union, we know this now, lost the race in about 1966/67 when the N1 rocket, their giant rocket, their equivalent of the Saturn 5 rocket that took men to the moon, couldn't get of the launch pad - it exploded on the launch pad. It just did not work and at that point, effectively, the race was lost.

1968 onwards, the U.S. had won and there was no way that the Soviet Union was going to get to the moon although the Soviets did carry on their moon landing programme, at least in theory, into the 1907s but they were never going to get a person on the lunar surface.

Graihagh - And what were the implications of all this racing and I suppose. ultimately, the Americans winning the race?

Richard - The biggest implication, I think, of the moon race was this massive advance in technology. It was actually, in retrospect, such an amazing period, such an incredible period. All the computers at mission control to enable these missions to happen, the development of rocket engines, the development of learning how to live in space. It's just incredible how much happened and how quickly it happened in that period of the space race. And then it kind of fizzled out rather quickly between Apollo 11 in 1969 and Apollo 17 (the last Apollo mission) in 1972.

10:52 - The space race of today?

The space race of today?

with Professor Ian Crawford, Birkbeck College, University of London

Are we racing to the Moon? Who are the contenders? And why the Moon over  Mars? Graihagh Jackson put her many questions to Ian Crawford...

Mars? Graihagh Jackson put her many questions to Ian Crawford...

Ian - There is a lot of renewed interest in exploring the moon. I'm not sure it's a race, perhaps it is at some level, but it's certainly true that newly emerging space powers, if you may call them that (China and India), have quite ambitious proposals to send spacecraft off to the moon and, in fact, both countries have already done so but they've got plans for more. I think part of this is geopolitical in the sense they want to demonstrate they've got this capability of sending things to the moon so they can join the major space parallels like America, and Russia, and Europe. Part of it is science driven though.

There's a recognition that, 40 years after Apollo, there's a recognition that we've still got a lot to learn about the moon. And then looking further ahead there's a realisation that the moon may have resources economically, raw materials that are valuable and might, therefore, be economically worth exploiting. So we don't really know the extent yet to which the moon might be economically valuable but this is, of course, another reason for wanting to explore it further so we can find out if it's got anything useful or not. So I think all of these things together really are driving the renewed interest in the moon.

Graihagh - What do you mean when you say geopolitical drivers?

Ian - In space exploration there are two geopolitical drivers. One is kind of a less optimistic driver. It's a bit like the cold war where countries are trying to compete or, at least, demonstrate they've got capabilities to try and aggrandise themselves on the world stage. But there is a more positive geopolitical driver and that's the collaborative aspect, that there's a realisation that space exploration is quite expensive to do. Individual countries probably can't do all they want to do on their own and this provides a stage, if you will, for nations to collaborate which is beneficial because nations may be at each other's throats in different other areas of their relations. But if they've got a few areas where they can collaborate and be seen to be collaborating, this can help build bridges between nations. There's one that already exists of course. I mean one of the reasons the International Space Station exists was a recognition, certainly in the U.S. congress, that by having Russia on board and other countries on board, it could help build bridges in the wake of the cold war.

Graihagh - So where are we up to today because I often think about it? Is it the jade rabbit, the Chinese probe isn't it? And then I think about the Russians talking about how they want to build a space taxi from the International Space Station over to the moon, so where are we at and who's doing what?

Ian - So China is quite active. I mean China did have their Changi 3 lander on the moon and that was a tremendous achievement but, yes, they have plans for several more and they're slowly but surely progressing that. The Russians also have proposals to send spacecraft to the moon in the next 5 or 10 years. In a sense, so does everybody but what's not quite clear is how realistic they all are. Some of this quite a lot of talk; some areas we can actually see stuff happening. Stuff is actually happening in China and so it's a bit difficult to know.

I am familiar with several Russian proposals that would have unmanned spacecraft land on the moon. Probably around the south pole of the moon, which is an area of some interest to lots of people at the moment.

Graihagh - So why is there this interest in the south pole - is there something there?

Ian - Yes. No spacecraft has ever visited the poles of the moon, north or south. Evidence has been growing over the last 10 or 15 years, that water ice is collecting in the bottom of these craters. If this is true, then this will be a very useful resource because, if we want to explore the moon further or explore elsewhere in the solar system, then water is a very useful material because you need it for life support t drink and everything. But, of course, you can break it up into oxygen and hydrogen so you can breath the oxygen or you can combine the oxygen with hydrogen as a rocket fuel. It's got multiple applications in space exploration but it's very heavy. I cubic metre of water weighs a ton of course, and if you've got to keep lifting water of the surface of the earth in ginormous rockets to use in space, this will make the cost of space exploration much higher that it would be if you had a local source of water. So yes, a lot of interest in exploring the lunar poles is to assess if this water is really there and, if so, how much is there.

Graihagh - And is there anything else on the moon that people perhaps talk about exploiting and using as a resource to help explore us explore say Mars and the rest of the solar system?

Ian - Certainly the moon has other things. It has metal, aluminium, titanium, silicon that you might use for solar cells. Exploiting these materials and manufacturing useful things out of them on the moon is, obviously, quite a long way ahead but, nevertheless, the moon does have these materials.

Something that people talk about on the moon as an economically useful resource is this helium 3 story, and there is an argument that helium 3 could be used for nuclear fusion power stations on the earth to provide our future electricity. Now I'm not myself an advocate of this for reasons I can explain if you want me to. I mean helium 3 is present on the moon, it comes to the moon on the solar wind and is implanted into the lunar soil. But no-one has yet demonstrated that helium 3 is a viable fuel for nuclear fusion reaction, so we don't actually know if we could use it. And even if we could use it actually, there's not all that much there anyway and so to get enough to provide electricity for the earth you'd be need enormous operations, strip mining of hundreds or thousands of square kilometers of the moon's surface every year. And so probably there's an easier way to solve the earth's long term energy requirements than mining lunar helium .

Graihagh - Yes I imagine so, and this mining problem is, I guess, because it all streams the surface and it's not concentrated in areas like we might think of mining metals and things on earth. But would it then be a good way to explore the rest of our solar system rather than dragging it back down to earth and using it as a fuel?

Ian - Nuclear power spacecraft... yes this would be very enabling, right. If you had a spacecraft that took only three weeks to get to Mars instead of 8 months, which is what current is taken, or could get you to the moons of Jupiter in a few weeks or month instead of years. Obviously, this would greatly open up the solar system and this would require new powered rockets of some kind. Now we're certainly not in a position to build one yet. I suppose it is true in the quite distant future, if you were able to build a nuclear fusion powered rocket, this would be a very enabling thing and if lunar helium 3 would be a potential fuel for such a thing, then yes that's an exciting but quite niche market, providing nuclear rockets to explore the solar system or maybe even beyond. So it's in the context of trying to provide all of earth's energy from lunar helium 3 that it becomes implausible. The amount you'd need to power a rocket would be much less and so then yes, it could become attractive in that context.

Graihagh - So paint me a picture of what's going to be happening in the next 10, 15, 20 30 years even. Are we going to be seeing more and more probes? Are we going to be seeing humans return to the moon perhaps 50, 60, 70, 80 years after the Apollo landings?

Ian - Well I certainly so. So the way I see it panning out, and the good news is from my point of view, this is what's essentially envisaged in the global exploration roadmap which means this is the way the space agency are thinking is after the ISA, return humans to the moon. Use human presence on the moon to of course learn a lot about the moon, it's geology and everything - a lot of science to do. But also develop human spaceflight capability that once we're confident that we know how to explore space with humans using the moon as a testbed, then to use that as a stepping stone literally and figuratively. A stepping stone that would take us to Mars and elsewhere.

So I hope that's the way space exploration pans out in the 21st century.

Graihagh - Would you volunteer yourself to go?

Ian - So I would have done, so I might still but I'm afraid in 2030 I'll probably be well past it, unfortunately. I mean I think, in a sense, there's been several lost generations post Apollo. There are people of a certain age like me who when they were 9 or 10 watching Apollo happen, thought this was the future, right, and yet it didn't actually happen for us but I hope it can happen for the younger generation. People like Tim Peake inspired a lot of people so what's Tim Peake's next mission going to be? Maybe it won't happen quite soon enough for him to have a chance of going to the Moon, but some of the young people he's inspired. I think this is what we have to hope that the space program ramps up to a level that many of the people who are school age now, that people like Tim Peake have inspired, can realistically hope that they might have a small but finite chance of going to the Moon or Mars.

21:38 - Rocketing the next generation into space

Rocketing the next generation into space

with Alison Kemp, The Perse School

The Apollo landings inspired youngsters to take science subjects, with the hope  that one day we would see humans living on the Moon. But this never happened after the Space Race was won. However, could there be a light at the end of the tunnel? Could Tim Peake's mission be responsible for rocketing the next generation into space? Graihagh Jackson visited Alison Kemp and her students at the Perse School in Cambridge to see...

that one day we would see humans living on the Moon. But this never happened after the Space Race was won. However, could there be a light at the end of the tunnel? Could Tim Peake's mission be responsible for rocketing the next generation into space? Graihagh Jackson visited Alison Kemp and her students at the Perse School in Cambridge to see...

Student - Yeah is was quite cool to see someone going into space for six months, I think. To go to the International Space Station for that long has been quite cool.

Graihagh - Would you volunteer to go up in space?

Student - Probably, yes.

Graihagh - It scares me.

Yes, it would probably be quite scary but also quite cool with the anti-gravity, because there would be no gravity and you could just float around. It would be awkward but cool!

Graihagh - This is a student from the Perse School in Cambridge. After Ian's comment, I thought it would be interesting to see if Tim Peake's mission had inspired youngsters to get to the lunar surface. These pupils are apart of Ecology Club, and they got some rocket seeds that were sent up into space with Tim Peake. They were then returned from space and the students grew them to see how microgravity and radiation might have affected them... Here's their Ecology Club teacher, Alison Kemp...

Alison - I'm a biology and a little bit of chemistry teacher her at the Perse. I've been here since September and, prior to that, I was a veterinary surgeon.

Graihagh - Oh wow! Quite a jump then?

Alison - Yes, but a very good one. It's been an absolutely fantastic experience working with all the young people here. They have so many questions and I'm constantly being challenged and thinking about new areas of science that I maybe wasn't before.

Graihagh - Like rocket seeds in space?

Alison - Like rocket seeds in space - exactly. That's not something I'd spent a long time thinking about but, when I saw the experiment was available, we had to do it. It's just such a fantastic opportunity to get the children involved with some real life science. It's something that will matter and something that, hopefully, will capture their imaginations a little bit and make them think.

So basically we got too packets of seeds.

Alison - One red and one blue.

Student - One had been in space with Tim Peake and one was just a normal packet of seeds. What we did, we planted both and we saw if there were any differences between the way they grew.

Student - We measured a percentage of the seeds which germinated, and how many leaves they had, and the height of them

Alison - The trays were randomised so we put sort of groups of seeds together, we mixed up the red and the blue. They all had the same lighting condition, they all had the same water availability as well, just to try and make it as fair a test as we possibly could do.

And what we did is we then just monitored the seeds. So we watched how long it took them to germinate, we then counted leaves on them, we looked at the height of the seeds, measured all the way up from the soil right up to the top of the shoot, and really just recorded what was happening and tried to spot any differences between the two packets as we went along.

Student - We didn't think they'd be much of a difference mainly because they're not really doing anything in space, they're just going up into space.

Graihagh - Even with microgravity and radiation and all those sorts of things?

Student - Well, they're still all packaged up and everything so it shouldn't make much of a difference.

Graihagh - I'm looking at the results on the wall and, actually, they're pretty close in terms of percentages.

Alison - They are very, very similar. We found there was a slight difference between our red and our blue seed but not really, hugely significant. Our red seeds tended to get a bit bigger, they're stalks were a bit thinner, and they tended to want to grow upwards towards the sky so I don't know whether that means anything. The blue seeds on the other hand generally stayed a little bit smaller but they were much more even. And the blue seeds - not as many of them made it until the final day of the experiment, so we did lose some of the blue seeds.

Graihagh - So what have you done with the results here?

Alison - We've put them into the RHS's database so they will be combined with results from all the other schools that have participated in the experiment. Obviously there are some employed scientists doing this experiment as well. We're not just leaving it to schools around the country but all the results are going to be combined. So they will obviously then be analysed and, hopefully, we should end up with some results over the next few months.

We're hoping to find out which packet of seeds went into space this week and so we're all waiting desperately for the email to come through to see whether our predictions were right.

Graihagh - I'd be just hitting refresh on my email constantly!

Alison - I have been doing that quite a lot of times this week. As soon as Tim Peake came back down I've been checking emails daily just to make sure I've not missed anything but, as yet, I'm still waiting to see the result.

Student - I think I would definitely get a career in science after this because I feel like I've got more of an insight into what actually happens in science, and I really enjoyed it.

Student - Maybe, I don't really know but yes, I think it has because I've got a bit more interested in what's actually happening and basically what happened there.

Alison - I think the experiment has just been a fantastic way of engaging the children with true science. Ultimately in school we do an awful lot of practical experiments. We're very, very lucky here but we as teachers know what the results going to be, we can obviously fiddle around with it to try and change things if we need to. This was something something completely new and that was actually really nice for me to be working almost at the same level as the students. We're all experimenting together. It's also a really good opportunity to talk about how we design experiments with them. It really highlights why we do things like randomisation, why we have to be very accurate with the measurements that we take because, obviously all these results are going to mean something and, potentially, could have an impact on whether we choose to grow rocket in space or whether we choose to grow other plants if we ever every eventually manage to settle on other planets.

Student - I think it's always nice to be involved in a big group study like this. You get to add to the community's knowledge like you said. I'm not quite sure how growing rocket seeds would help us live on the moon but...

Graihagh - Well, we need food.

True, true. But I think it's always a great thing to do.

Alison - With many subjects, the way to best engage young people is to get them involved, get them seeing what jobs in that field actually do. I don't think there's any better way of encouraging children into science than actually getting their hands dirty and getting involved.

Student - Well, I think this might contribute to example the MarsOne mission because what we're trying to do here is a one way trip to Mars and then we're going to set up a greenhouse there, which can be built in 6 months. And we're trying to basically populate Mars, if you can say that and I think this might help because now investigating how seeds would behave in space and whether we could actually grow seeds there, and how this would affect it or whether they're edible after we've grown them there as well. So, I think that's quite interesting and it's going to expand our knowledge.

Student - Yes, it would be really cool because you would be basically starting a new world and using this experiment and this study, you can ways of growing food. And then, if the world gets too populated, you can move there.

A huge thank you to all the students at the Perse School for their contributions to the programme: Charlie Toff, Isaac Baillie, Henry Butler, Paolo Cicuta, Ella Cowell, Alice MacDowell, Annouska Duggan and Shnithi Yasuthan.

- Previous How do octopus camouflage?

- Next Tobacco can help treat malaria

Comments

Add a comment