Gene Genealogy & The Lost Family

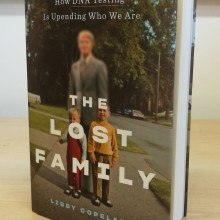

One of the biggest tech booms of the past half decade has been direct to consumer DNA tests. Most of them promise to reveal the secrets of your family history, usually the ethnic origin of your ancestors or the identity of a long-lost cousin. And very often they work really really well. The results come in the post, and with them come both answers and new questions - questions that thousands, tens of thousands of people now have to figure out how to ask. In this episode, a new book from journalist Libby Copeland about a sociological phenomenon and its effects, both grand and intimate.

In this episode

01:26 - The Lost Family: revelations from DNA tests

The Lost Family: revelations from DNA tests

Libby Copeland

In Libby Copeland's new book The Lost Family, she traces the butterfly effects of direct to consumer DNA tests that reveal family histories - with startling accuracy. Tens of thousands of people are finding lost relatives in their results, or finding out the people they call flesh and blood are genetic strangers. As more and more of us sign ourselves up to these databases, is it changing how we understand our own identities? Phil Sansom sat down with Libby for an interivew...

Libby - I first started exploring the concept of DNA testing, home DNA testing, and its popularity and its sometimes unexpected results when I wrote a feature story for the Washington Post. After that piece ran I started getting emails, so many emails that I couldn't keep up with them; ultimately over 400 emails from readers who wanted to tell me their own DNA testing stories. You know, "I tested it and this is what happened", "I tested and I discovered this astonishing thing". And as I was reading these responses, I thought, "man, this is an American phenomenon. This is potentially a global phenomenon. This is a sociological phenomenon. This is a book."

Phil - What sort of things were people saying?

Libby - There's just so many ways in which DNA testing can play out for people. I mean, obviously for many people they're looking for some access to family history, and in many cases that's just what they get. People are very curious where they came from. They often don't know other than a vague sort of, "oh, I think I'm Irish", or "I think I'm Italian". And so they kind of want to get a little bit more granular, they want to see what else they can find out. "Where in Ireland might I be from?" "Could I figure out who my great grandparents were?" That sort of thing. So in many cases that's sort of the standard thing that you discover, and the companies that market these tests - companies like Ancestry and 23andme - they really play up this notion that you're going to discover your roots, and you're going to get this pie chart and it's going to tell you that you're 27% 'this' and, you know, 15% 'that', and that's very exciting. But very often there are things that people don't expect. They're buying these often on a lark or they're giving them as gifts, they're very popular Thanksgiving and Christmas gifts here. And what they wind up finding is something that they never were looking for. So they'll discover, for instance... the most common significant, unexpected result is that you discover that the man who raised you, who you think of as your father, is not genetically related to you. Or you might discover that you have a half sibling you didn't know existed. Or you might discover that somebody you thought of as a full sibling is a half sibling. There are many cases where people discover that they were donor conceived, so conceived by a sperm donation; or perhaps they discover that they're one of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, even more than a hundred half siblings. Some cases they might discover they're adopted. Now most people set out knowing that they're adopted because that information is typically disclosed. But for some older adoptees, they might not know. In other cases, they set out looking for their birth families, adoptees set out looking for them ,and they're able to easily find them because the size of the databases makes that just incredibly easy at this point to very quickly find, say, a first or second cousin who allows you to unravel the identity of your genetic kin.

Phil - And is it DNA testing that's changing this in a big way?

Libby - DNA testing is extremely accurate when it comes to predictions of genetic relationships, so "are you my relative?" Now it can't necessarily tell you precisely what the relationship is, but it can tell you a range of genetic overlap, basically; you and I share certain identical segments and that can predict the level of relationships. So for instance a half sibling relationship looks really different from a third cousin relationship, and that's a very close relationship. A sibling relationship, a parent child relationship, a first cousin relationship, all those things are so close that they can help you unravel more tendrils of information. And that simply does not come out wrong for people, right? You don't get a prediction that someone's your brother and they're actually just a genetic stranger to you or a fourth cousin. So that stuff is really accurate. The ethnicity estimates, which are very popular in the United States, where you get a little pie chart that tells you you're a certain percentage 'this' and a certain percentage 'that'; those are a little bit more nuanced and can vary from company to company because they are what the companies like to call "an evolving science".

Phil - What you're saying, it sounds like, is that when you're connecting to people, DNA is pretty good at that.

Libby - Yeah, DNA is amazing at that. It really is.

Phil - What's the effect on people when they have this kind of revelation? And what's the effect on lots of people when lots of people start having this kind of revelation?

Libby - That's what I wanted to discover in my book. And I really think that this is going to be studied as a sociological phenomenon in decades to come, because I think this is the moment when everything changed; when all of a sudden we have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that sometimes we weren't told the whole truth about who we were or about the past. It's very complicated and it depends on the person. Some people go through a process of grieving for the families that they didn't get to spend time with because they did not know they were related to them. Some people go through a process of wrestling with, "well, if this man's my genetic father and this man raised me, what does that mean?" And the conclusions that they come to are often quite nuanced and beautiful. They'll say, "well, the man who raised me is my father and this man is also something to me. This man who's genetically my father is also important to me." So they often take perhaps a whole lifetime to wrestle with that. It's not simple to go for 50 years thinking that you came from these two people and you are 'this thing' in terms of your ancestral history, and then discover that say 50% of what you thought is not the case, at least as far as genetics is concerned. And that's something that people wrestle with. They feel sometimes guilt, they feel anger, or they feel bittersweetness, they feel joy. In fact, in the United States there's a number of psychologists who've begun to specialise in what it looks like when a person discovers an unexpected result by DNA testing, and how they., what the... basically the process, the emotional process that they have to go through in order to understand that and make peace with that. So it's incredibly complex.

Phil - You had a great quote about this in one of your early chapters. You said, "we human beings are the meaning makers, each of us a product of a particular time and place with ideas about what we value, and indeed what we hope to find when we look." That really struck me. What did you mean by that?

Libby - I think when I wrote that, I was thinking about the history of genetics research and how tied up it is with eugenics and the way that we can interpret bits of scientific information, but we are not objective. We're subjective storytellers. So I found this throughout the book, and quite apart from that facet of the early history of genetics, which is that we are all subjective in terms of how we interpret the scientific information that comes to us from DNA testing. So for instance, I am half Ashkenazi Jewish through my mother, but I identify very strongly with that and less so with my dad's ancestral history, which is British and German and Swedish. And I don't think that we're foolish or wrong to be subjective in our interpretations of what certain cultural things mean to us. If you're raised with say Sicilian heritage, that might speak to you far more than say your father's heritage, which might be Japanese for instance. So the point I was trying to make in that section and throughout the book is that when it comes to understanding "what am I ethnically" or "what is a father" or "what is a sibling", all of these relationships and these sources of meaning are things that we have to discover for ourselves. We find our own language for them. We find our own labels for them. We get to decide what's a father, what's a sibling, what does it mean to be this ethnicity or that, and we apply our own perspective to that journey

Phil - In that context is DNA even relevant in and of itself?

Libby - It is and it isn't, right? So I think the danger that people worry about is that we'll think about the process of discovering one's genetic identity in a kind of binary way. So "I thought I was this, now I know that I'm that"... there's a great ancestry DNA ad that they run here in the States that shows this guy discovering he's one thing instead of the other and he basically throws away his kilt and puts on his lederhosen. It's that kind of "well goodbye to all of that!" And of course that's troubling. But I think the reality is, for most people it's not binary. And yes, it is meaningful to discover that because it's another layer of identity, right? I was telling you earlier that I identify very strongly with my mother's ethnicity; well part of the process of DNA testing has been discovering my father's side. And in the fall we went to Sweden and we were able to meet my dad's second cousin, which is access to the past and to really my family's past that we would not have had without DNA testing, because we found these cousins through the databases, which is pretty amazing. But it's not as if I say, "well now I'm all Swedish!" Right? It's a 'yes and' situation. It's like, "yes, this is true, and also that". So for somebody who discovers for instance that, the man who raised them, that man is not their genetic father; in many instances the people I interviewed would say, "well this man, he is still in my heart. He's still my father. I have that relationship with him" - if they started out with a close relationship - "and now I also have this other man in my life who is, say for instance, in this imaginary scenario, my donor father. And I have a relationship with him, but he does not supplant my father. He does not take over for my father. My father is still my father." So it's not as if we dismiss everything that came before, but it's also not meaningless. It's incredibly meaningful to people to know their true ancestral histories and genetic identities. And I have to say, the vast majority of people who discovered something surprising, even troubling in their DNA results, told me that they were glad to know. Because even if that truth was hard to reconcile with, there's a value in simply knowing the truth.

Phil - And what was it like for you to find your Swedish family?

Libby - It was astonishing. You know, I mean it's... I have never been able to feel that the past is so present to me. And I don't know if this is different in the UK and in Europe, where people I think probably grow up with a better sense of their ancestral roots, a better sense of access to the past; particularly if you stay in the same geographical area, you might know what your roots are going back. But here in the States where people tend to be made up of lots of people from lots of different countries, right, lots of different immigrants from lots of different places, we tend to feel somewhat cut off. And so to be able to say, "we were able to go there and actually see the grounds of the farmhouse where my dad's grandmother lived before she emigrated" - that was an incredible gift to me.

Phil - I suppose that also has particular relevance for a lot of African Americans in the US, who were brought over as slaves and don't have any link that they know of to maybe even two, three generations back.

Libby - Absolutely. That's actually something that a number of folks who I interviewed for the book talk about, you know, it's this ability to get around the limitations of the fact that their ancestors were brought over in chains and completely cut off from their roots. And the commercial DNA testing companies historically have not been super awesome about certain kinds of ancestries. So they tend to specialise in European white ancestry and that tends to be what they're better at, in part because those are the people who are mainly in the databases and buying the tests, and in part for historical reasons. But certain companies have been working on improving their results. For instance, one man that I interviewed talked about how he was able to really get down to a granular level in terms of understanding the particular people that he had come from along one of his sides, and he said that this was an absolutely profound thing for him, that there was no paper trail for him. There was no way for him to achieve this by trying to look back at records. But through the DNA and as the process has evolved and gotten better over the years, he's certainly been able to get more granular results. Through the DNA he could get incredibly precise about this one particular branch of his family and he was just sort of astonished and really touched by this.

Phil - Now like you say, a lot of people have that reaction; but I was surprised to learn from your book that for genealogy alone, DNA testing is absolutely enormous. And there's so much money and so many corporations involved that...

Libby - Yeah. In fact, testing for ancestry has historically been more important than testing for health. At least in the US, that has been the thing that has been selling the kits. And so the ads that the companies have run - so the major companies in the US are Ancestry, which offers an ancestry DNA kit, and 23andme, and then there's also MyHeritage DNA and another company FamilyTreeDNA - if you look at the ads that they have been running, they're entirely about discovering your roots here in the US. The shift to health testing: that's a much more recent move. And basically what's happened is that they have essentially, the experts say, vacuumed up all the early adopters in the United States. So all the people who would test for ancestry purposes who are ready, willing, and able to plunk down $99 to find out their roots; those people are all basically already in the databases, and they tested for that reason primarily. And now the companies are starting to shift towards health results because they're hoping to offer more to people who didn't already test for ancestry purposes. But yes, in the United States ancestry has absolutely been the driving force behind commercial DNA testing.

Phil - And where's that going to lead?

Libby - Well, it's interesting now because there has been in the last six to ten months a slowdown in kit sales here in the US, and there's a couple of reasons for that. One is, as I mentioned before, there's the fact that the companies have basically already gotten all the early adopters who were interested in ancestry and family history to test, and so they've found that that's slowing down as a result. There's also some thinking - and the cofounder of 23andme Anne Wojcicki talks about this - that there is concerns about privacy here in the US. And privacy can mean a lot of different things, but basically that slowdown means that it's a little bit unclear where things are going. I think ultimately the databases will continue to grow and that's what's behind the pivot towards health testing and testing for disease risk, and traits, and things like that that several of the big companies have recently turned to. We're going to keep growing their databases, but they're going to do so with an emphasis on, they say, eventually being able to predict your risk for certain health conditions, for example. And they haven't really been able to deliver on that quite yet to the extent that I think some consumers would hope, but I think over the next few decades that's... we're going to start seeing that happening more and more.

Phil - And do you think everyone's going to be DNA tested? Maybe just in the US, but after a certain amount of time? And there'll be a big family tree of close to everybody?

Libby - Yeah. I think that, whether or not it's everyone... although there are some who people think that there's going to be a time when all newborns will be sequenced at birth, basically, in developed countries full stop; but that's sort of a theoretical thing that could be coming down the road, but we'll put that to the side. Right? So at the moment there's anywhere from 35 to 40 million people in these commercial DNA databases, the vast majority of them American, and then also folks from the UK, from Australia, from Canada. I do think they are going to continue to grow. And I think that the point is that even if they never encompass every single person, it's almost as if everyone is opted in in any case. Which is to say that if you have a genetic family secret within your clan, that's going to be discovered. Because even if you never test, it sort of doesn't matter anymore. We've reached a saturation point where anyone is discoverable by DNA, even if they never test. So for instance, if a man helped conceive a child 40 years ago and he declines to test, he can be found because his aunt tests or his child tests or his sibling tests. And through the process of triangulation it's relatively easy to discover his identity using genealogical methods and social media. So I think we're heading towards the point where it's increasingly not a choice of whether to opt in or not opt in. You're effectively opted in by the decisions of others.

Phil - And when it comes to families, you in your book describe a lot of people as 'seekers' or becoming 'seekers' when it comes to their own family history and genealogy; and the tagline of your book is "how DNA testing is upending who we are"; hen you say it's upending who we are, are people becoming 'seekers' or are we becoming people who eventually won't need to be 'seekers' anymore?

Libby - Maybe down the road? It's sort of hard for me to envision what that would look like, but eventually someday none of this stuff will be a surprise anymore, right? And I can't tell you when that someday is, but right now we're in the process of discovery, and that process is very disruptive to people's lives. So we're sort of in the place where we are learning that the past isn't always what we've been told it is. We're sort of in the place where we're learning that our families aren't always what we assumed that they were. And that struggle, that process, that kind of emotional reckoning, that's in some way implicating all of us right now and making us all into seekers. I think of this as the decade that changes the American family in many ways.

Phil - And do you think DNA is the catalyst or do you think DNA is just something in the background?

Libby - I think DNA is the catalyst, but DNA alone wouldn't do it. So in order to make a family discovery, in order to... let's say I'm searching for a half sibling. I heard rumours that I might have a half-brother somewhere who is 10 years older and I need to figure out, now I'm an adult I'm going to see if I can find him. I would start with commercial DNA testing: I'll spit into a tube or I'll swab my cheek and that's the beginning. But in order to really figure out where he is, if he's not in the database and I'm looking for him, I would need other tools. So I need social media. I might need access to genealogical subscription services. I might need access to yearbooks and things like that, right? Online. It's this interesting combination of the data that's out there that we all put out there right now. I mean, we all have Facebook accounts and we all have some presence online, it's the rare person who doesn't exist online. So we all leave these little breadcrumbs. So it's the combination of the DNA testing in concert with this ability to find people online, to research our family histories, and also our present day families online. And those things together are creating this moment.

Comments

Add a comment